From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 82 – first published in 2019.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Bryen collection, OBA archives, Jim Scaysbrook, Bob Rosenthal.

Five straight World Championships. That’s the enviable record of a motorcycle that was never beaten from the time of its conception to the point of it being mothballed. The 350cc Moto Guzzi is perhaps the singularly most successful racing motorcycle of all time, and an object lesson in sublime simplicity and brilliance of execution.

Traditionally, Moto Guzzi had concentrated on the 250cc (Lightweight) and 500cc (Senior) classes in Grand Prix racing, but with Norton and Gilera (and soon MV Agusta) getting plenty of publicity through success in the 350cc or Junior class, it was decided in 1953 to enter that class as well. The works machines, finished in drab green, were not entirely original designs, being initially over-bored versions of the 250cc single overhead camshaft Gambalunghino (Little Long Legs) racers, taken out as far as possible to a bore and stroke of 72mm x 78mm) for a capacity of 317cc. When new crankcases were available, the bore was able to be increased to 75mm giving a capacity of 345cc and later to 349cc when the stroke was lengthened by 1mm.

Although the factory was hard at work on its fabled 500cc V8 and also had the in-line four cylinder racer, a 500cc version of the single was also developed for use on tight circuits where the V8 would be considered too much of a handful. Moto Guzzi’s brilliant engineer Giulio Carcano ensured that the development of the singles never stood still.

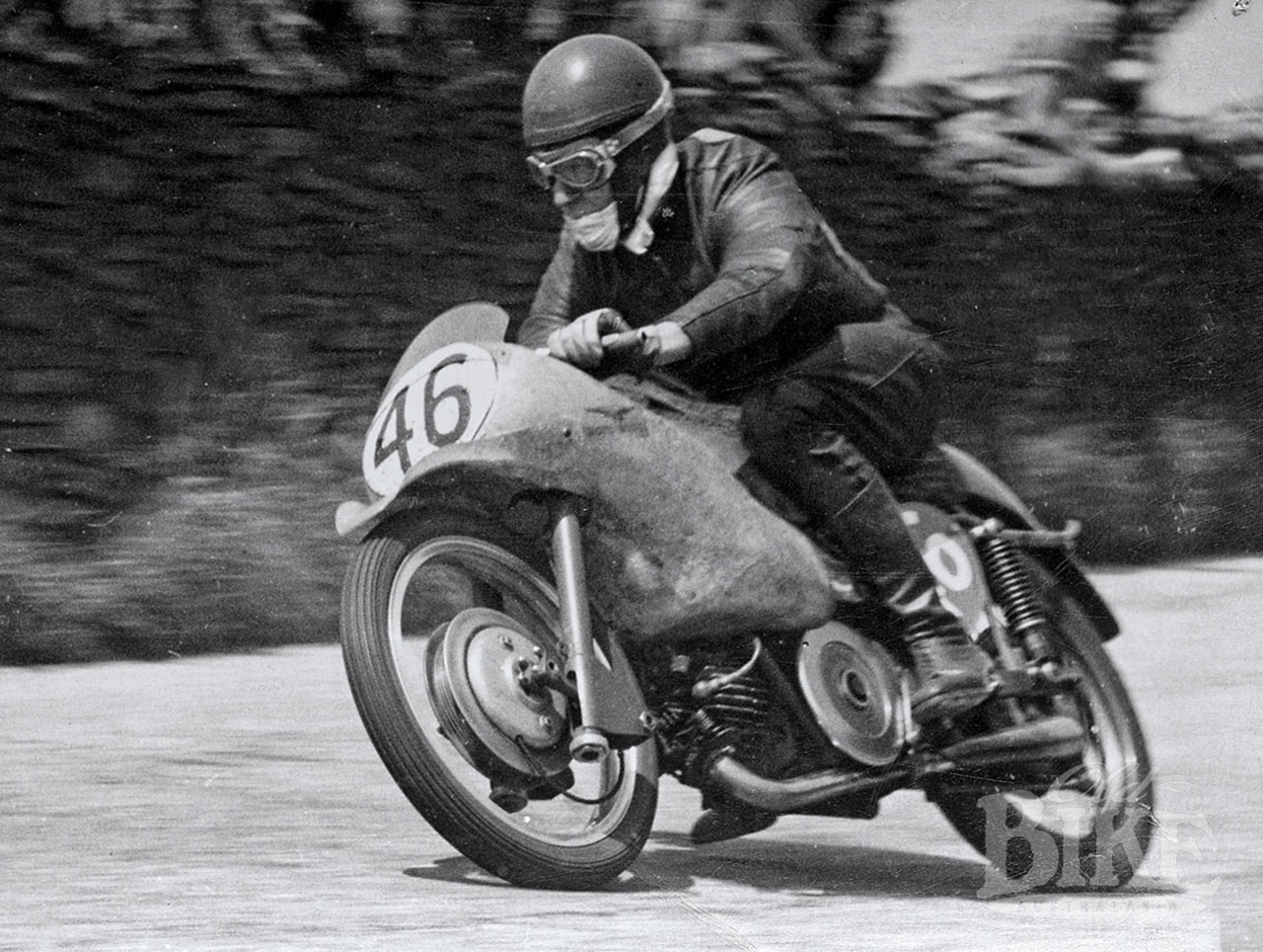

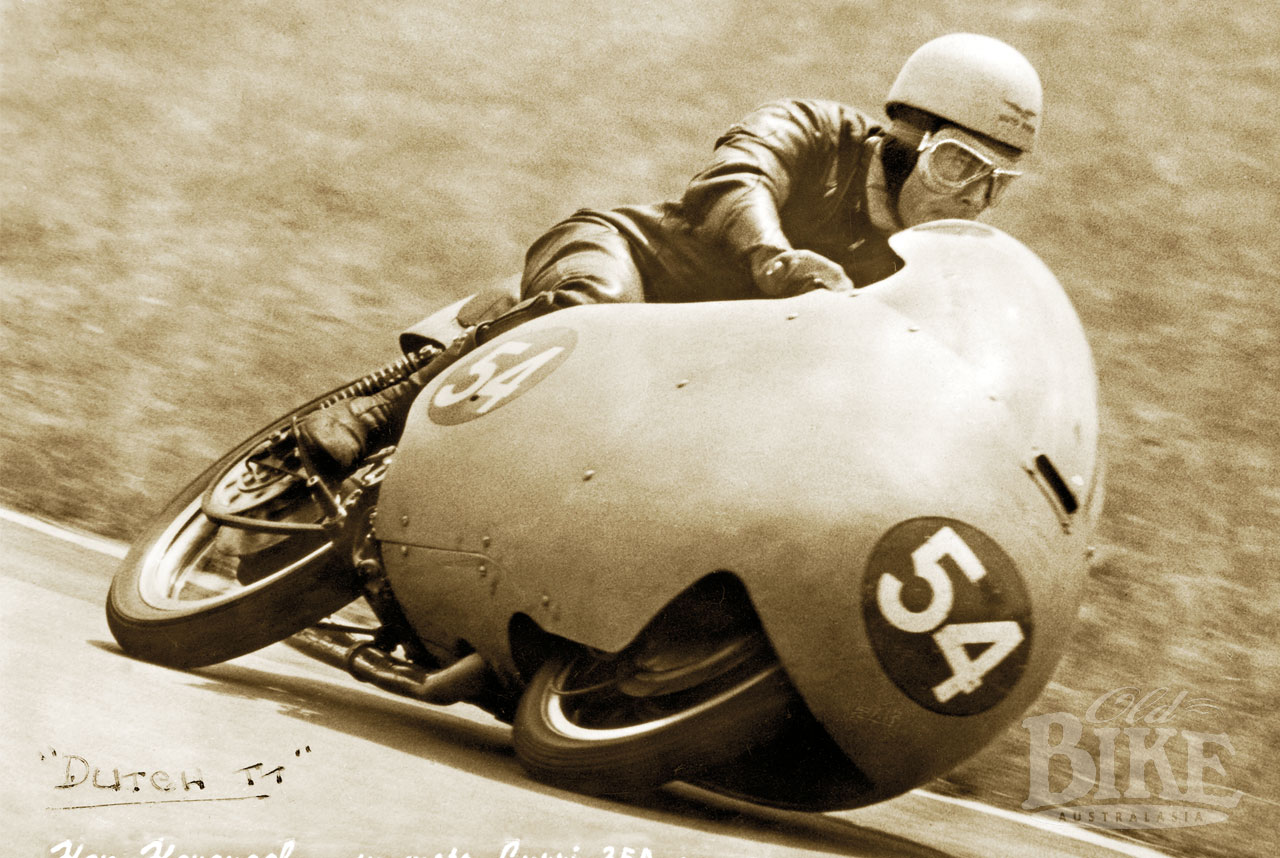

The new 350 for the 1953 season appeared conventional in the extreme, with a choice or four or five-speed gearbox (later standardised to 5 speed), magneto ignition, 35mm carburettor and an all-up weight of just 122kg. The results were instantaneous. At the opening round of the 1953 World Championship, the Isle of Man TT, Fergus Anderson finished in third place on the 317 in the Junior TT, just behind the works Norton pair of Ray Amm and Ken Kavanagh. Three weeks later, Enrico Lorenzetti easily won the 350cc Dutch TT after Anderson was forced to retire with clutch trouble, but not before smashing the lap record by 4 seconds. At the Belgian GP on the super fast Spa-Francorchamps circuit, Anderson and Lorenzetti ran riot, finishing way ahead of the pursuing Nortons, and Anderson repeated the treatment in France and at the Swiss GP. That left just the all-important (for the Guzzi, MV and Gilera factories) Italian Grand Prix at Monza where Lorenzetti and Anderson again took the top two spots of the podium, the Englishman being crowned World Champion.

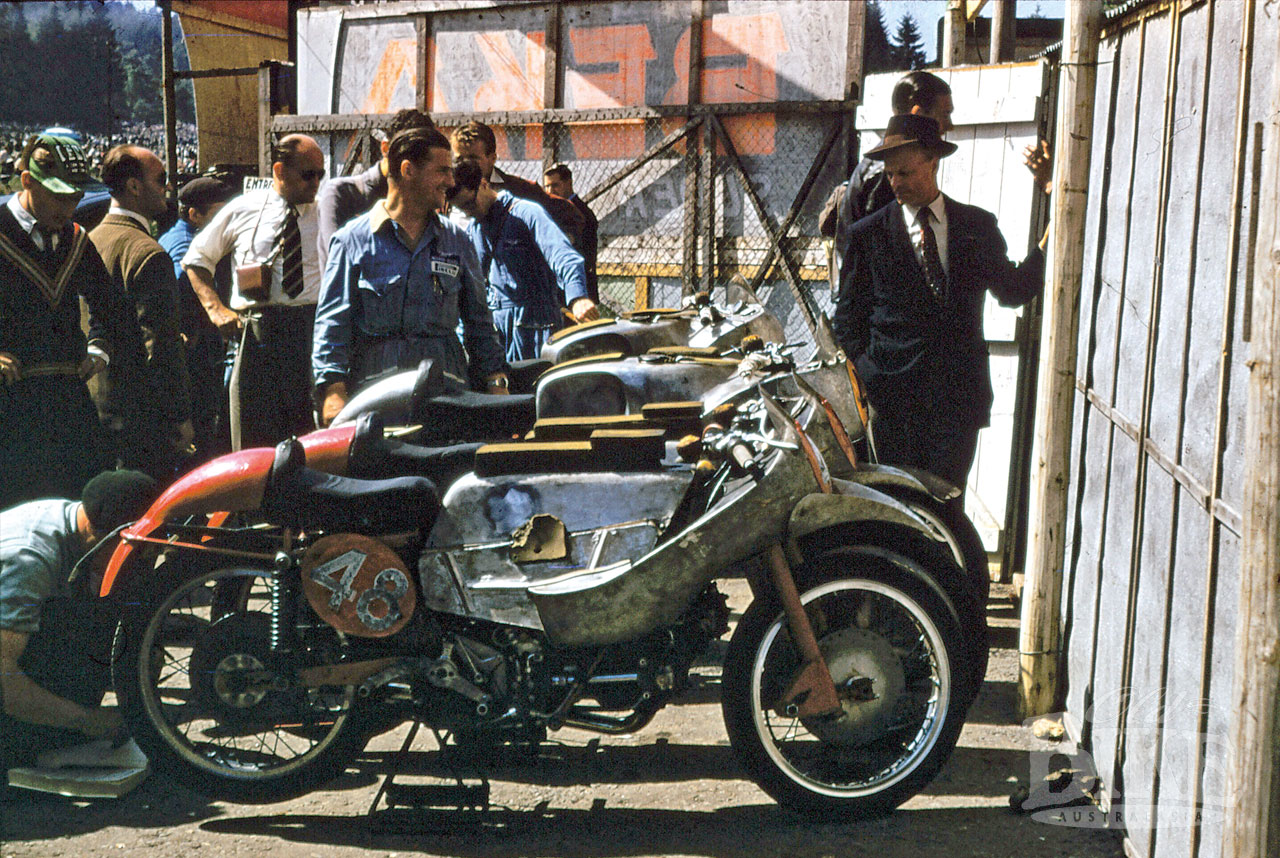

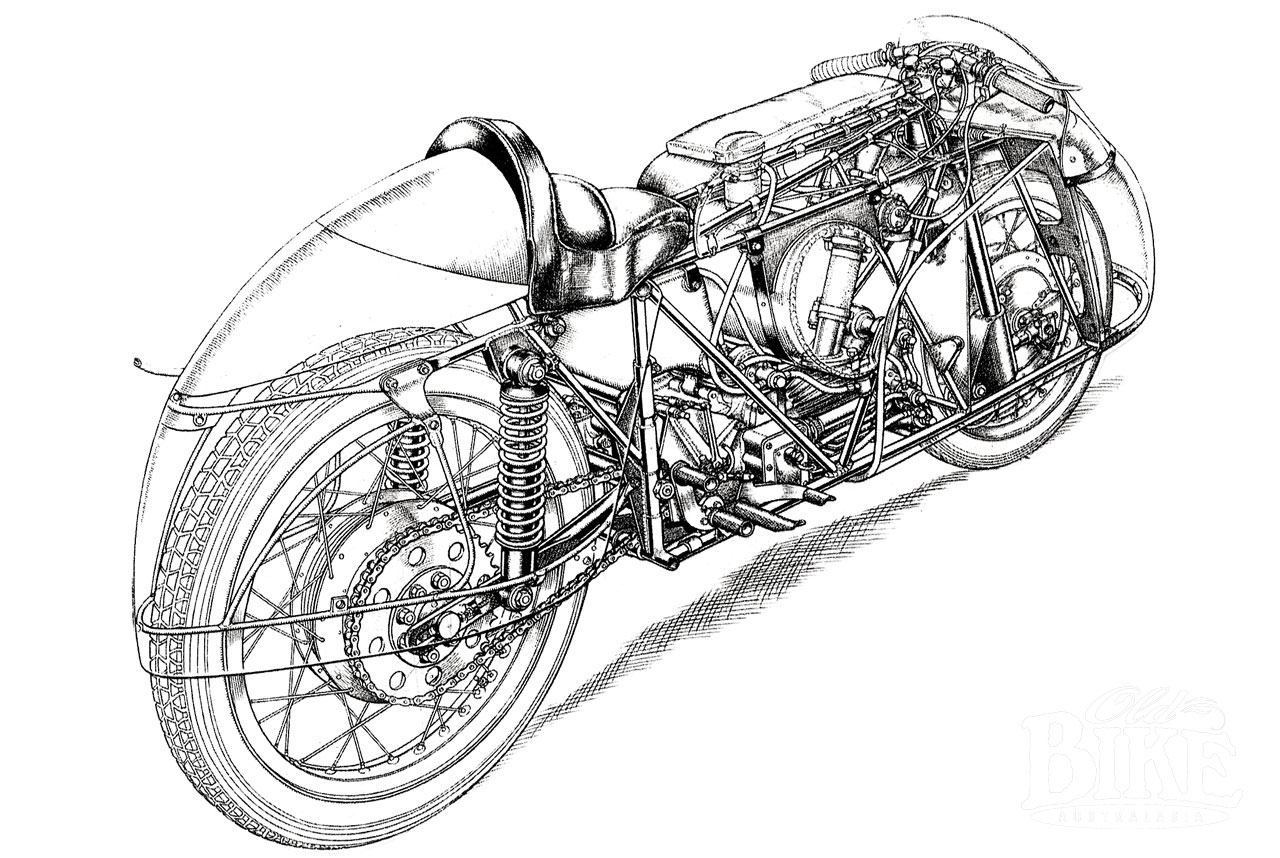

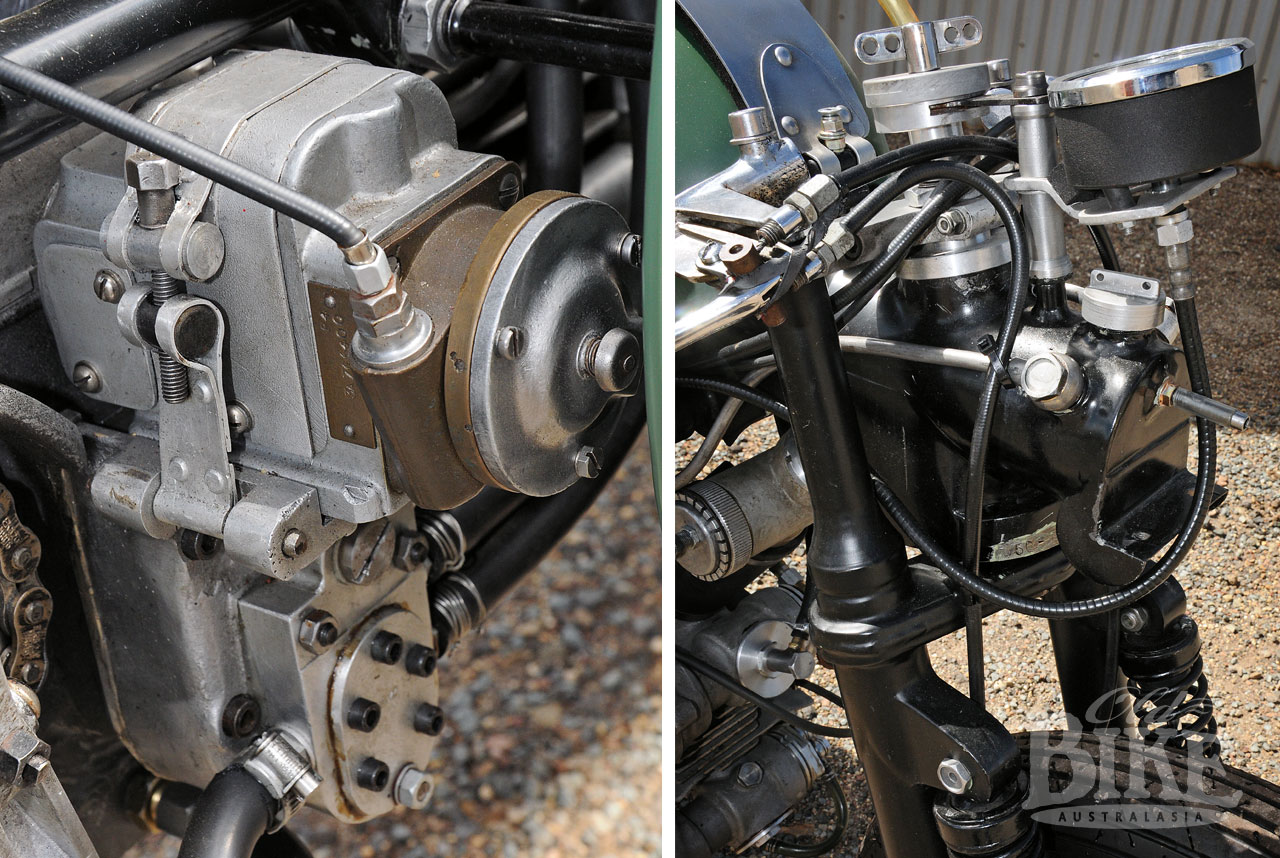

It had been a master class, and a massive slap in the face for the opposition which was increasingly preoccupied with multi cylinder designs, and for Norton, who virtually gave up the chase. For 1954, Moto Guzzi upped the ante further with a completely redesigned 350 featuring a multi-tube ‘trellis’ frame, or what the British referred to as a “Bailey Bridge” triangulated space frame. Full streamlining (referred to as “Dustbins”) was permitted for the 1954 season, and rather than just hang a fairing on an existing frame, as many did, Moto Guzzi designed a completely new frame to incorporate it. As a fully integrated part of the design, the small diameter top frame tubes extended past the steering head to form the front fairing mount. To lower the centre of gravity, pannier fuel tanks were cast into the side sections of the fairing, which was made from hand beaten electron alloy and painted only in a green primer. Mid-season, a ‘barrel tank’ was mounted crossways in the centre of the frame, with the filler neck under the pad on the dummy tank in the conventional position, with fuel supplied by a pump on an extension of the contact breaker shaft. A new double overhead camshaft head sat atop the cylinder which had grown to a bore of 80mm, with the stroke reduced to 69.4mm. Power was quoted as 35 horsepower at 7,800 rpm. Once again Fergus Anderson was crowned champion with victories in the Dutch, Swiss, Italian and Spanish GPs. At the season’s end Anderson accepted an offer to become Moto Guzzi team manager and (temporarily) retired from racing.

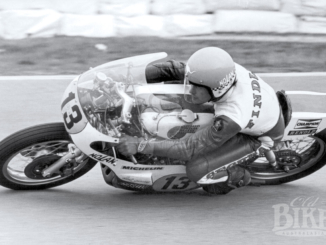

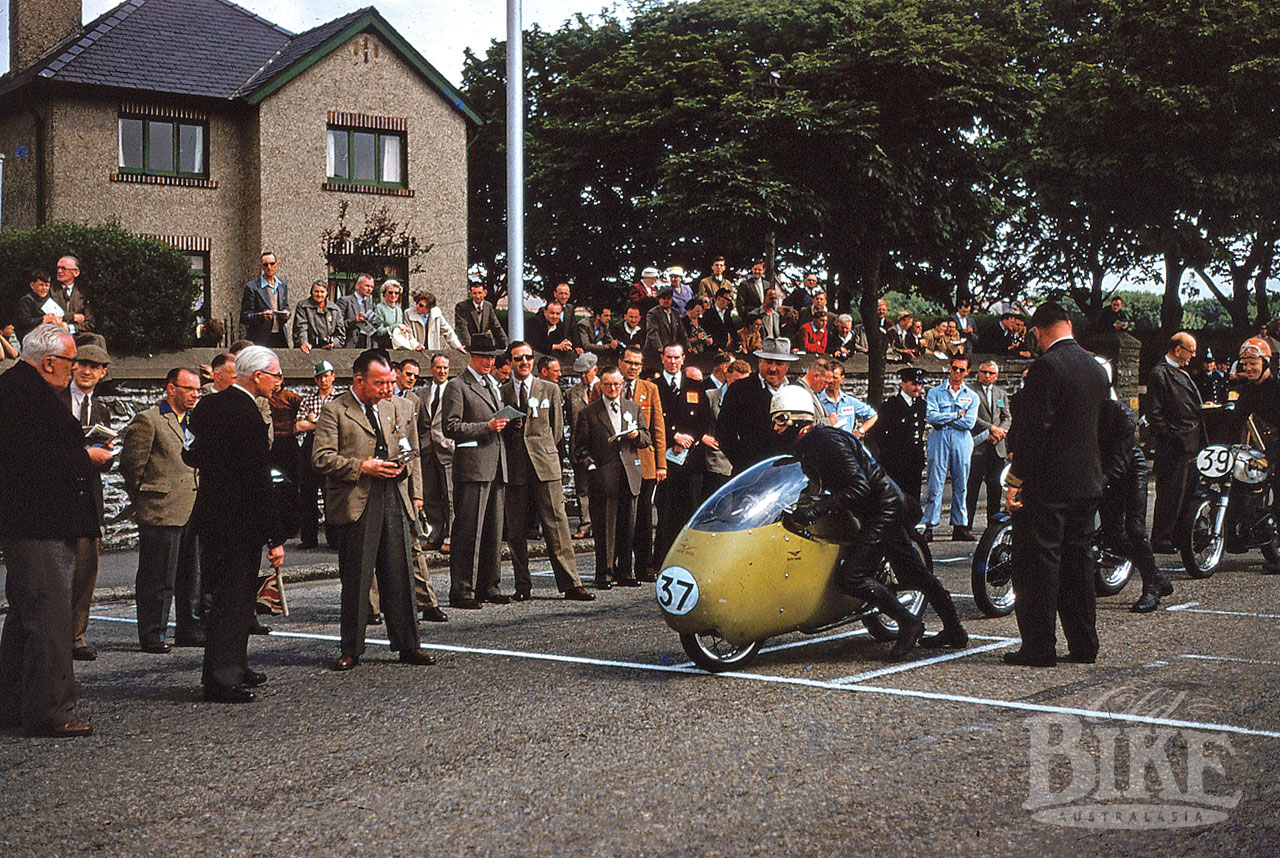

Replacing Anderson and Lorenzetti was Englishman Dickie Dale, Duilio Agostini and Australian ex-Norton teamster Ken Kavanagh. The works 350s now used a new short stroke engine of 80mm x 69.5mm and performance had been further enhanced by a new one-piece full fairing as a result of testing in the factory wind tunnel. Following the Isle of Man TT, where he was loaned a 350 and won, Bill Lomas joined the team on an unofficial basis, which ran away with the Manufacturers’ championship by winning every one of the seven rounds, and riders taking four of the top five positions in the overall standings. With four wins, the crown went to Lomas, who was rewarded with a two-year contract to ride for the factory team.

Out here in the Colonies, enthusiasts could only marvel from afar at the exploits of the Moto Guzzi team in Europe, with their fabulous singles and the even more fabulous, at least in specification, 500cc V8. So it was front-page news when it was announced that Lomas and Dale would compete in Australia during the southern summer of 1955/56, bringing with them one 350cc and one 500cc single, plus a spare engine for each. Not unexpectedly, the duo won as they pleased at meetings in Perth, Mildura, Bandiana, Mount Druitt and Fishermens Bend.

By 1956 the 350 had reached close to its ultimate specification, with another new frame (actually similar to the original 1953 design) around a large diameter top tube which doubled as an oil tank. To make the engine unit easier to remove, it was hung from the top tube in a trellis structure. The forks and front brake from the V8 was used, with English Girling spring/damper units. The works team consisted of Lomas, Dale, Kavanagh and Agostini. Kavanagh opened the season with victory in the prestigious Imola Gold Cup, then went on to become the first Australian to win an Isle of Man TT, taking out the 1956 Junior. However once again Lomas was the man to beat, easily retaining his title with a further three victories, but the team had begun to suffer reliability issues linked to the coil ignition system that proved very difficult to diagnose.

Lomas could well have made it a triple crown in 1957 had he not crashed heavily in the non-championship season opener at Imola, sustaining injuries that would force him to retire from racing. However Lomas’ misfortune was Keith Campbell’s gain, the Australian elevated in status in the works Moto Guzzi squad that he had joined in mid-1956, albeit at the expense of Kavanagh, who made what turned out to be an ill-fated move to MV Agusta. Campbell had been given a 350 and a 500 to bring to Australia for the 1956/57 summer season, and he managed several wins, despite a crash at Phillip Island where he dislocated his shoulder and broke a thumb. For 1957, the works 350s had been further subtly refined with the engine in its final specification of 75mm x 79mm, 38 horsepower was available at 8,000 rpm. To replace the troublesome coil ignition, the team returned to magnetos. Saving weight became Carcano’s obsession, and the magneto went some way to achieving this by eliminating the dual batteries, plus the points and coils. Magnesium replaced steel wherever possible. The result was an all-up weight of between 98kg and 102 kg depending on specification for individual tracks such as the Isle of Man for which a larger fuel tank was used.

Back in Europe, Keith lined up for the opening Grand Prix in Germany but failed to finish with gearbox trouble. Second place in the Isle of Man TT followed. Campbell bounced back from his injuries to take out the Dutch and the Belgian Grand Prix, with his new team mate and fellow Aussie Keith Bryen third in Belgium. Even better was in store at the Ulster Grand Prix where Campbell and Bryen finished 1-2 in the Junior GP, sealing the title for Campbell, who failed to start in the final round at Monza after crashing the V8 in practice. Then came the bombshell, when Moto Guzzi, along with Gilera and Mondial, announced they were quitting racing, leaving their squad of works riders to contemplate their futures.

It was the end of a glorious era that had begun in 1921 for Moto Guzzi, with the race bikes mothballed and largely forgotten. During the era when Moto Guzzi was under the ownership of the Argentinian businessman Alejandro De Tomaso, much of the contents of the former race shop gradually disappeared or was scrapped – a travesty in the history of one of the world’s most successful and revered racing marques. Some of the former works machines were saved from oblivion and today reside in the factory museum at Mandello Del Lario. These range from the exotic machines of the ‘twenties through to modern versions of the transverse v-twins, but for sheer functional efficiency, none can match the green 350cc singles that swept all before them from 1953 to 1957.

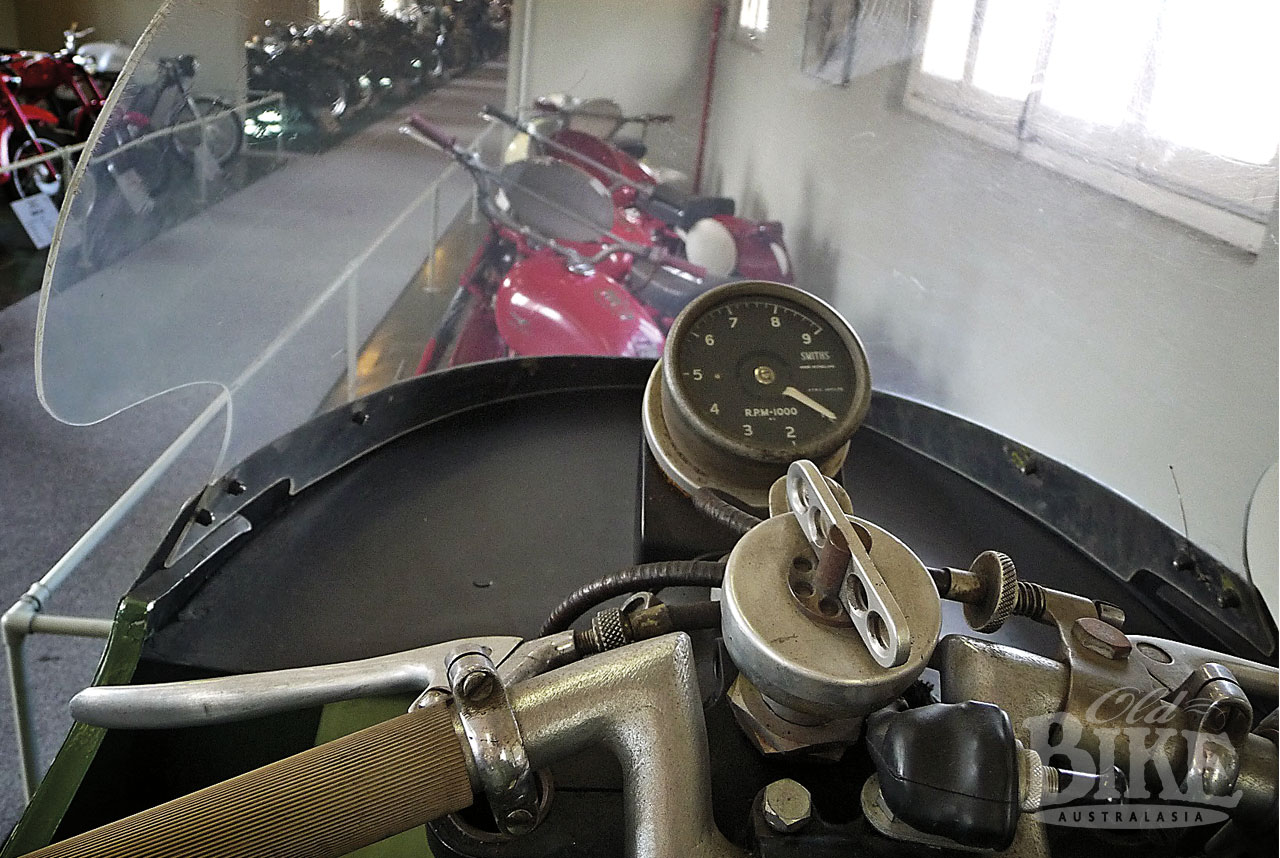

From Mandello to Melbourne

More than sixty years have passed since the great 350cc Moto Guzzis last fired a shot in anger. Today, visitors to the Moto Guzzi museum on the shores of Lake Como, a spectacularly beautiful part of northern Italy and a setting that mesmerised at least two of the factory riders, Fergus Anderson and Ken Kavanagh, can gaze upon examples that have thankfully not been restored. Yet, clothed in their full enveloping green full fairings, the mighty 350 World Championship winners can largely go unnoticed by visitors who instead marvel at the unclothed V8 on display, or any of the earlier single, two, three or four cylinder racers.

Recently, an example of the works 350cc Moto Guzzi has arrived in Australia to be come part of the sensational collection of racing motorcycles owned by Ron Angel. Ron also owns a Moto Guzzi V8 – one of the “continuation” models assembled from original or remade parts by the son of the co-designer Umberto Todero. But exotic as the V8 is, it wasn’t his first choice.

“I first set eyes on the 350 single Guzzi at Bandiana (at the circuit inside the Army Camp on the NSW/Victoria border where Lomas and Dale appeared) in 1956,” says Ron. “I thought it was the most sensational thing I had ever seen, it made the other bikes look old hat. I had no idea at that stage that I would eventually own one, but I never stopped thinking about it. But nothing happened, I never heard of one for sale and basically gave up on the idea, that’s why I bought the V8 when it became available. Then, out of the blue, I was contacted by a fellow in Europe who keeps his eyes open for me, and he told me a 350 may be coming onto the market.

“It certainly wasn’t cheap, but you’d expect that, so after a bit of discussion we settled on a price and here it is. The engine number shows it is a 1956 build, but the unique part about this bike is that it has a six-speed gearbox, not five. From what I understand, only two six-speed gearboxes were made, and the other has disappeared. As to who rode it during the period I do not know, but the model is special to me given the connection with Keith Campbell, Australia’s first World Champion.

“I am reluctant to start it given the magnesium crankcases are 63 years old and undoubtedly fragile. If anything were to happen in that regard it would be a tragedy, so I think I will be keeping the 350 purely as an exhibit so that people have the opportunity to see one up close and appreciate what a marvellous piece of work it is.”

Ron’s 350 appears to be in the specification that it would have raced in 1957, with magneto ignition, the 56/57 frame, dustbin fairing with the higher screen, and 40mm Dell’Orto carburettor. The only visible deviation from original specification appears to be the 18 inch wheels and tyres. In the day, the 350s used skinny 2.75 front and 3.00 x 19 inch racing tyres, which today are unobtainable.