Having played his part in Hitler’s downfall, young Ken Rivers emigrated to his brother’s dairy farm at Victor Harbour, just south of Adelaide. Despite the Government’s catchcry ‘Populate or Perish’ 1952 was a time of significant unemployment and Ken decided to use that time to take a gander at his new country.

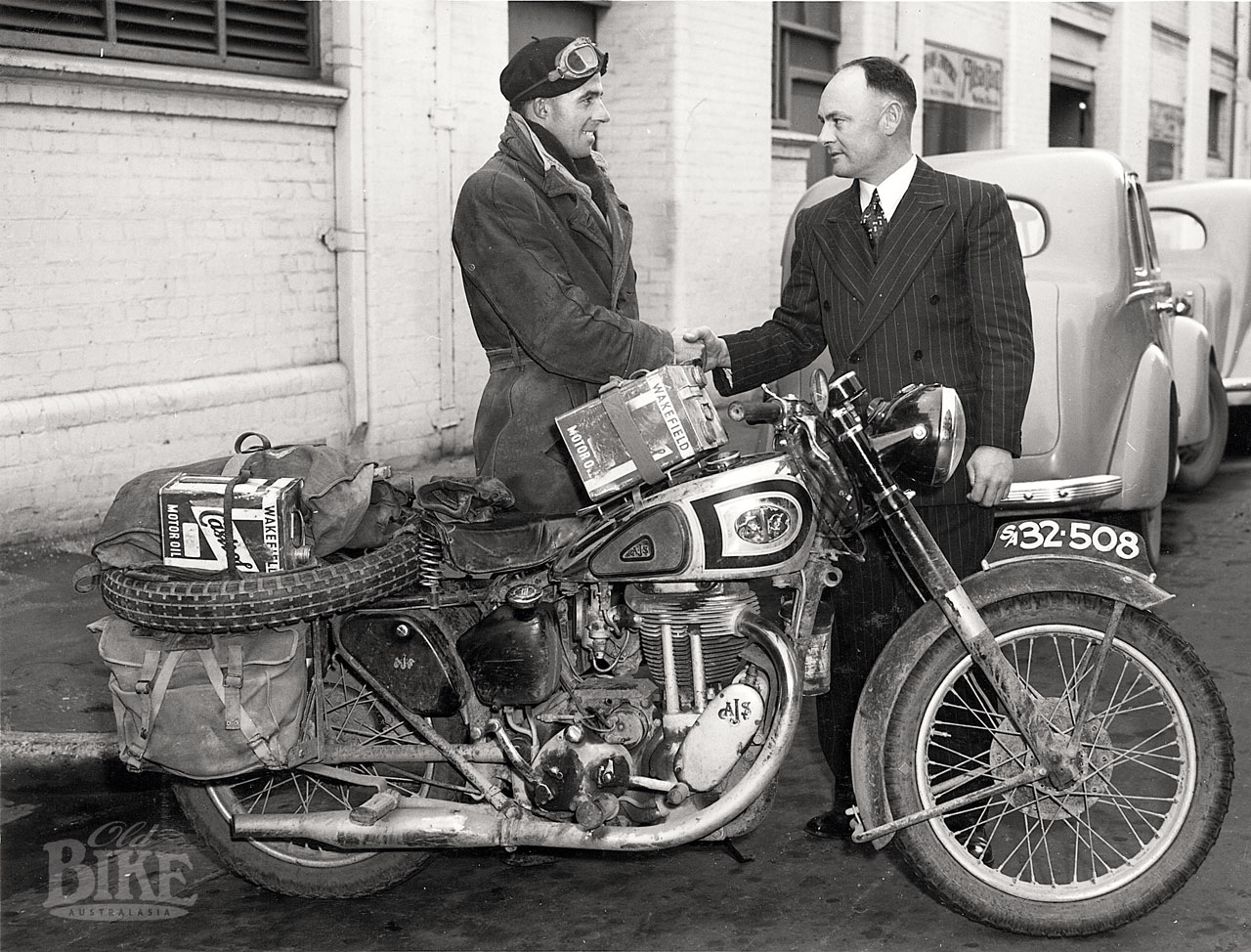

Unlike his pre-war predecessors he had no desire to set any speed records on his circumnavigation of Australia preferring instead to indulge in a leisurely holiday. Rivers, who had toured extensively ‘at home’ in Great Britain and Europe, chose two wheels for the autonomy he preferred at a cost he could afford. In this he was assisted by Arnold Hansen, Sales Manager of British Motorcycle Sales in Adelaide (a World Speedway star of the 1930s), and Bill Winspear from C.C. Wakefield – the distributors of Castrol Products – both of who could see the promotional advantage of having a personable young man of British pluck and determination conquering the colonies whilst using their products.

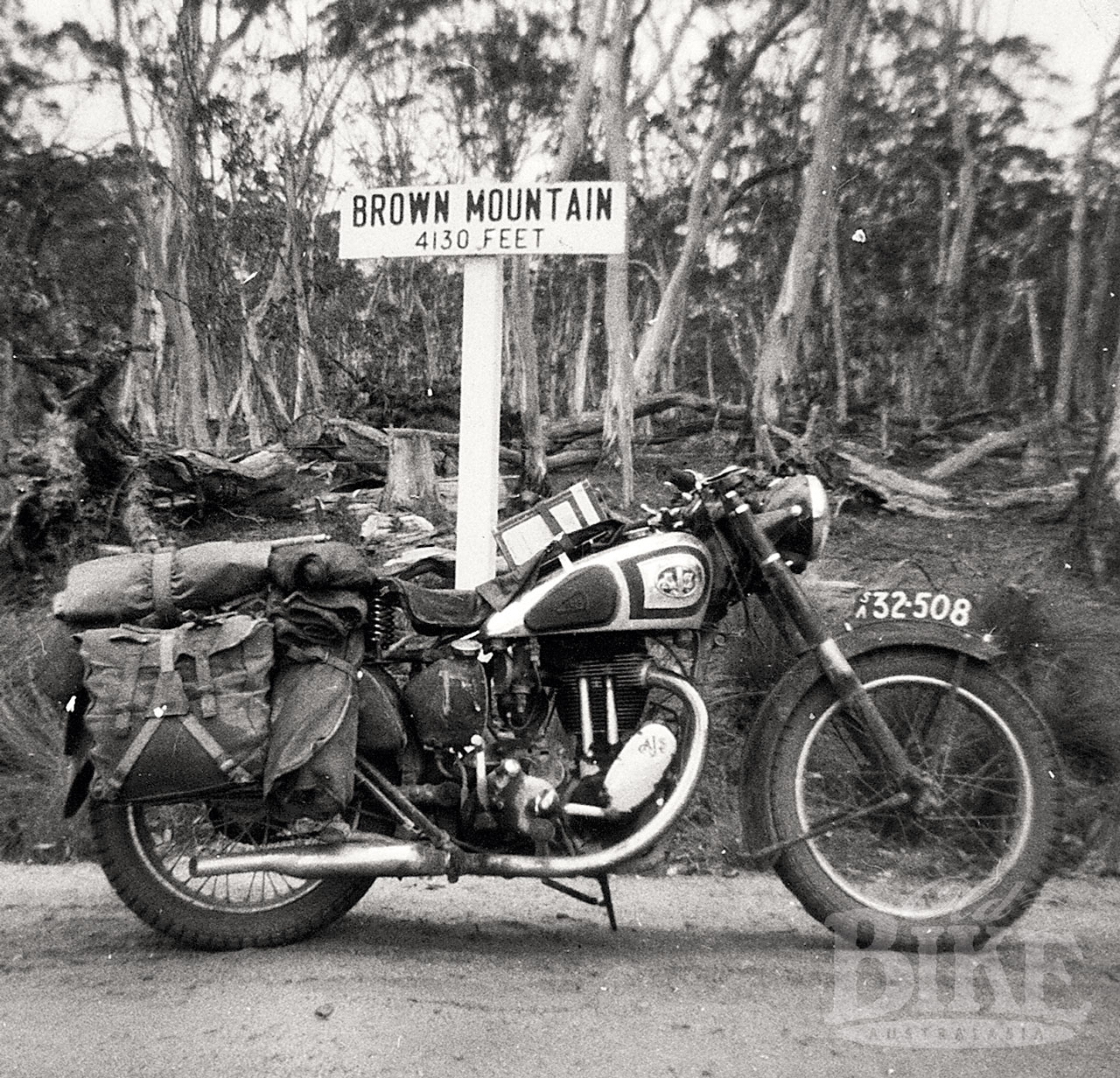

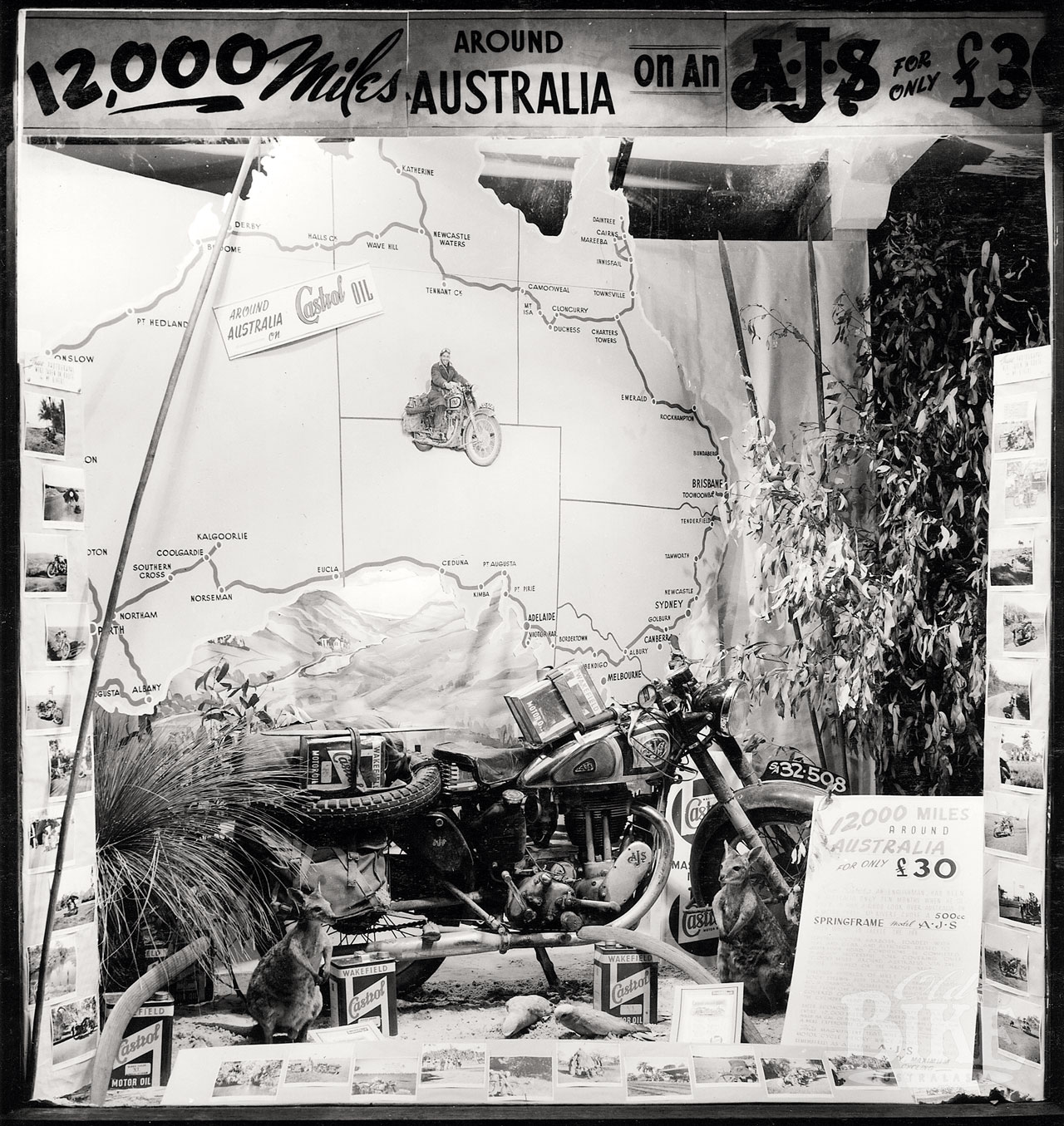

The machine chosen for the task was the new A.J.S. 18S Springheel model, a robust 500cc single deemed ‘capable of covering vast distances through arid uninhabited territory under a sweltering sun and tropical rain’. And hopefully of surviving the 12,000 miles that Rivers expected to cover on his extended journey.

Unfortunately the detailed log kept by Rivers on his pilgrimage – and later verified by Wal Murphy, Secretary of the Motor Cycle Club of South Australia – has been lost, but whilst the eastern capitals were linked by bituminised ‘highways’ the western regions of our vast continent remained much the same as when Arthur Grady, Jeff Munro and Jack Bowers performed their epic circumnavigations between world wars. Besides, Norman ‘Wizard’ Smith had already raced around Australia in a Pontiac in the remarkable time of 45 days but at no time did the ‘Wizard’ spend time enjoying ‘the luxury of lazing on the beach and bathing in the warm sea’. Rivers was clearly on a mission of hedonism rather than haste.

Bundled in his heavy leather greatcoat, helmet, goggles, Home Guard Gas Cape and long rubber waders, the A.J.S. all but buried under his substantial kit – decorated by a prominent array of one gallon Castrol tins – Rivers looked anything but a man headed for the beach as he departed Victor Harbour in 1952. True to his intent, he took the scenic route whenever the choice was available and five days after passing through Bordertown crossed the Sydney Harbour Bridge reporting ‘first class bitumen roads all the way’ along the south coast. He stuck to the coast up to Wauchope before turning inland across the New England Ranges. It was mid winter, cold and wet; naturally Rivers took the first opportunity to head back to the coast from Tenterfield noting that ‘in Queensland many people go barefooted and it was odd to pass motor cyclists wearing only shorts’. Whilst in Brisbane he called on Vic Huxley, another speedway ace of the thirties, and took the opportunity to service the A.J.S. in Vic’s workshop.

Good progress through the pineapple, banana, mango and paw-paw plantations was made to Bundaberg where Rivers hit the first gravel roads – and corrugations, “the corrugations at their worst can be compared to bad French and Belgian pavé. It is best to increase speed to around 40 mph for a much smoother ride. However, sometimes the road is too bad and one has to plod along in bottom gear!” Little did Rivers realise there was much, much worse to come and by the time he crossed the Tropic of Capricorn near Rockhampton he’d entered what he termed ‘the land of the long distances’ and struck inland to Emerald, Clermont, Charters Towers and thence to Townsville which afforded a welcome change; a change which he was quick to take up with trips out to the Great Barrier Reef and Palm Island, from where he describes fascinating demonstrations of spear and boomerang throwing. Clearly the fifties were simpler, if less politically correct, times.

Rivers would have been one of the very few motorcyclists to venture as far north as Daintree and visit the abandoned gold mining districts of the Atherton Tableland but eventually he returned to Townsville to continue his circuit and it was here he struck his first real taste of the outback, discovering sand, bulldust, cattle grids and the fact that an Emu can keep up a constant 35mph pace until it hits a fence. Rivers also notes the monotony of following the railway or a line of telegraph posts disappearing over the horizon, however it wasn’t all monotony as he recalled “another hazard of the tracks of northern and central Australia are the innumerable creek and river crossings but they were all dry when I passed. There are no bridges and the approaches are particularly steep and sandy. From Cloncurry to Mount Isa via Duchess there are 139 creek crossings in 143 miles.”

Though Mount Isa and Cloncurry are but 100kms apart as the crow flies the iron laden Selwyn Range is so rugged the Barkly Highway was not completed until many years later. However Rivers did enjoy the bitumen road west to Tennant Creek then north to Darwin; the horror stretch surveyed by motorcyclists Jack Bowers and Frank Smith barely twenty years earlier was now a doddle according to Rivers “The ride up the bitumen to Darwin was most pleasant. I enjoyed tea and home-made cakes at a café miles from anywhere, served by an English lady who had but recently arrived from England. I enjoyed the beer served ice cold in the comfortable bar of the Dunmarra Hotel, followed by large, juicy steaks. I enjoyed camping at the picturesque camping site at Katherine by the side of the shady river banks above the crocodiles”. Clearly Rivers enjoyed this leg of his journey.

And obviously the bitumen was also to his liking for, on his return south, instead of taking the more trafficable route from Katherine to Wave Hill he continued on to Marlinja before turning west on to the remote – and little known – Murranji Stock Route that follows the northern boundary of the vast 11,000 square kilometre Newcastle Waters cattle station. What possessed him to choose this narrow cutting through the almost impenetrable lancewood and bullwaddy known as the ‘ghost road of the drovers’ is anyone’s guess and Rivers makes little comment other than describing a track that “was inches deep in a very fine dust resembling French chalk which found its way into everything. As I rode, I could hear it grinding in the rear chain and I had to keep on making chain adjustments. Soon after Wave Hill I had to cross the wide Victoria River. It proved a particularly stony crossing, best described as trying to ride along the shingle at Brighton beach; with my heavily laden machine it was no picnic.”

The going simply got tougher as he passed through Halls Creek and continued towards Fitzroy Crossing. “Through this lonely, inhospitable terrain I carried on for mile after mile. The dry air shimmered with burning heat, then, rounding a corner, I saw something that made me rub my eyes. There lay an oasis with a plantation of banana trees and below the trees a shady pool and a green lawn where I camped for three days. On the second day some natives on walkabout turned up. The husband carrying just a spear or two and the wife, some paces behind, carrying all the household belongings as well as the youngest child slung on her back. I thought of the contrast between those natives and honeymoon couples seen at Bournemouth, with the husband staggering under the weight of two suitcases and the wife carrying her handbag.” And no doubt enjoyed the fact he remained a bachelor.

As Rivers progressed his enjoyable moments were punctuated by less pleasant times; the hospitality he encountered at the remote outback homesteads was most gratifying, the long days through the ‘pindan’ country between these convivial occasions were not so agreeable according to Rivers’ later recollections “I had my first taste of really deep sand, and with the heavy load on the rear of the machine I had great difficulty in keeping a straight course. As I had many miles of sand in front of me I experimented with weight distribution. Strapping my tent over the headlamp and down on to the front fork was a distinct improvement. I also deflated my tyres to around 14 lb pressure.”

The exotic delights of tropical Broome countered this hardship in spades but there were more obstacles to come as Rivers reported. “Between Broome and Port Hedland I encountered the worst track that I had met anywhere in Australia. With long stretches of deep sand aand thick dust. Near La Grange I came off four times in one day. The only damage was a bent footrest and a bruised ankle.”

It’s insightful to note that Rivers’ accounts of these tribulations were revealed only later when, hosted by A.J.S. and Castrol, he toured the UK to provide a series of presentations about his odyssey to fellow enthusiasts. Whilst on the actual journey itself, the short missives Rivers sent back to Arnold Hansen at British Motorcycle Sales reflected nothing but praise; witness the following examples. From Townsville ‘The A.J.S.’s Springheel has been a joy to ride on the bad roads’. From Mount Isa ‘The A.J.S. has stood up to the hard conditions as smoothly as ever’. And from Port Hedland ‘I have negotiated the 400 miles from Broome successfully. The track was easily the worst I have been through. The A.J.S. has stood up to the tough going magnificently’. Sponsorship may have been in its infancy however Rivers clearly knew where his bread was buttered.

Rivers continued down the west coast to become the first motorcyclist of record to complete the ‘round trip’ via Carnarvon – instead of the inland track through Meekatharra – and include a scenic ride through the great Karri forests to Cape Leeuwin and Albany before returning to Norseman for the home run across the Nullarbor.

Rivers’ eventual return to Adelaide was preceded by a phone call to Arnold Hansen. As Don Southcott a mechanic at British Motorcycle Sales recalls, ‘that phone call quickly stirred us up and we alerted all the interested parties we could, including all our own staff, our mates from Lenrocs (the Triumph and Norton agents) and J.N. Taylors marine section. As we were situated in Hyde Street – a small sidestreet – this, to us, seemed like a crowd’.

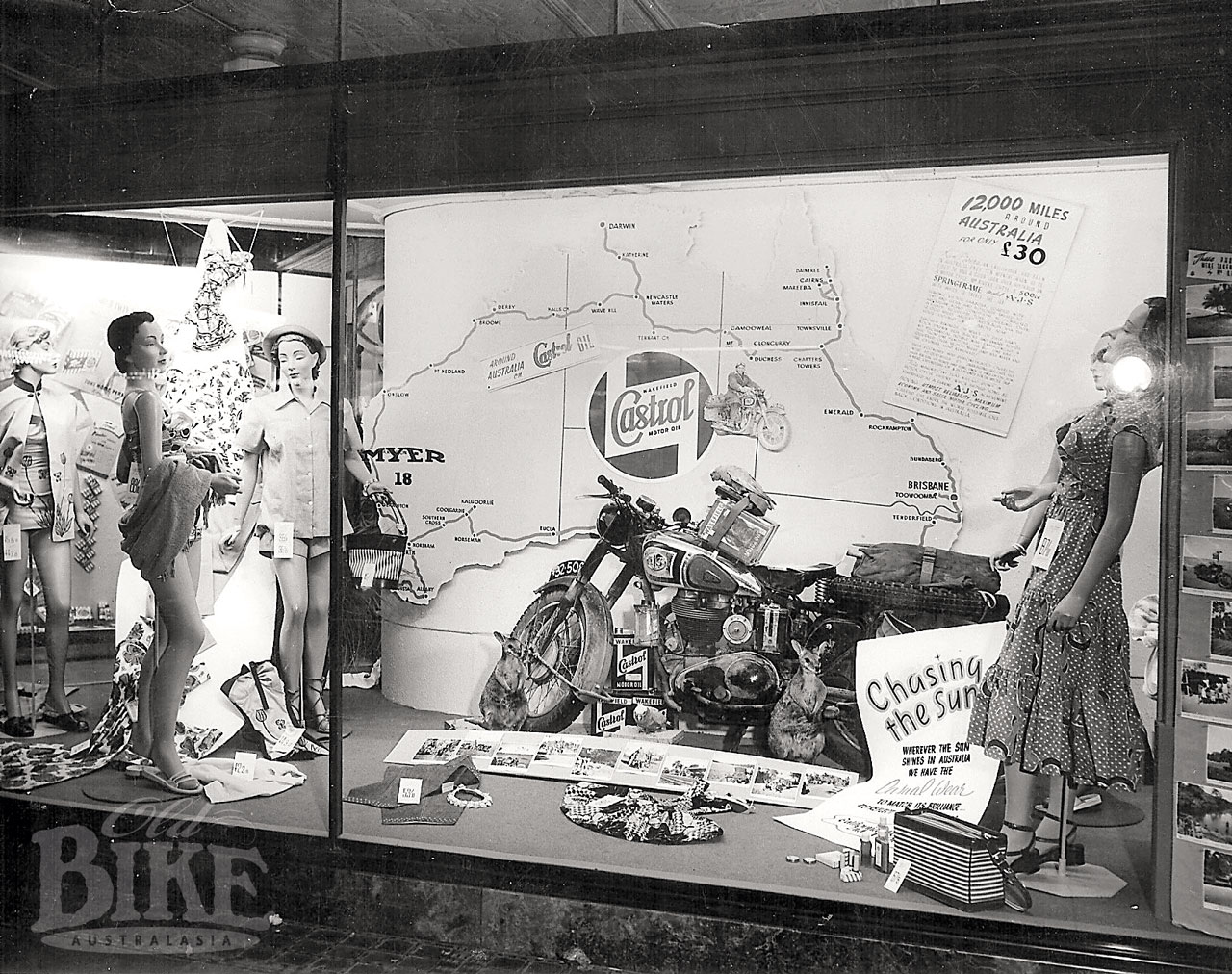

In total Rivers had ridden over 12,000 miles in four months and the only troubles he reported were but a single puncture and a broken clutch cable. Petrol consumption averaged over 90 m.p.g at a total cost of thirty quid but there was no mention of CO2 emissions and, in spite of the incredibly dusty conditions, he used only 12 pints of oil. Arnie Hansen and Bill Winspear had their faith rewarded and River’s A.J.S. went on immediate display in BMS showroom; and was later moved to Lenroc’s window before moving upmarket to an incongruous display amongst scantily clad mannequins in the Myer Emporium.

Ken Rivers briefly returned to his brother’s dairy farm at Victor Harbour before accepting a position as State Sales Representative for C.C. Wakefield; a position he held for some years. In 1953 he undertook a similar ride on an A.J.S. around New Zealand before a promotional tour back in the motherland; a tour which instigated a spate of advertising for the man and the machine that Conquered a Continent.

Still going strong

More than half a century after Rivers’ epic odyssey, motorcyclists remain at the forefront of discovering the most daunting ways of criss-crossing our vast 8 million square kilometre continent. Many do so under the umbrella of events such as the Australasian Safari where, as long as a rider can avoid bouncing off the flora and fauna whilst following the cryptic route instructions, they’ll arrive at the overnight bivouac where sustenance and medical aid is laid on and camaraderie assured.

Other riders form groups and are supported by a 4WD carrying the swags, the steaks and a bottle of Bundy or two. Even the most intrepid adventurers usually ride out in pairs – often with each bike loaded with up to 100 litres of fuel and 100 kilos of provisions. More importantly they’ll carry a GPS, a Satphone and often an Emergency Position – Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) for contact with the ubiquitous Royal Flying Doctor Service.

Sixty years ago it’s probable that all Rivers carried was a Bex, a Band-Aid and, at best, a mud-map; which makes his feat all that more remarkable.

Story: Peter Whitaker • Photos: Castrol archives, Darren Lamb.

Thanks to the following enthusiasts who assisted in putting a little flesh on the bare bones of Rivers’ great achievement: Alan Wallis O.A.M., Don Southcott, Kerry Moore, Darren Lamb, Christian Gyde, Bill March, Chris Bennett at History S.A., Brian Bingley at State Library of S.A., David Baker, Sharon Ellis and Stephen Hooper.