From a wobbly start, the Chesterfield Superbike Series had rounded off the 1973 season in a big way, and Chesterfield took little convincing to continue their involvement.

The original ‘5000’ tag disappeared for the simple reason that prizemoney was boosted to a total of $7,000 – easily the most lucrative such event in Australia – with $4,000 going to the winner. The poorly supported Bathurst round was dropped, leaving the entire series to be contested over four rounds at Amaroo Park.

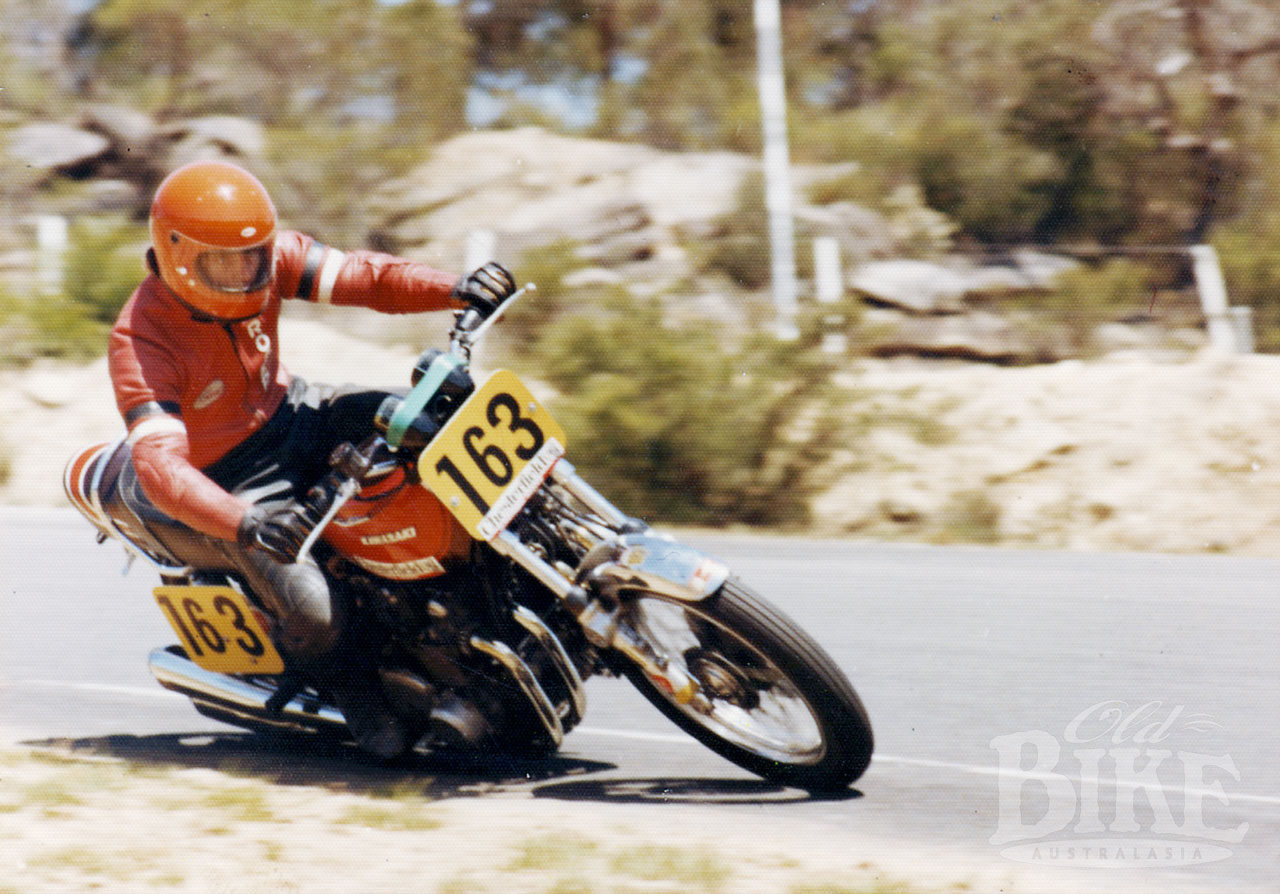

To clean up the grid somewhat, and hopefully encourage more of the big four strokes into the field, a new rule stated that to be eligible, machines had to be based on road bikes over 500cc, but with a fairly open hand as far as performance modifications went. Nevertheless, the H2 Kawasaki was still the machine of choice, and arguably the main protagonists – reigning champ Len Atlee, Warren Willing and Garry Thomas, were all mounted on the 750 triples.

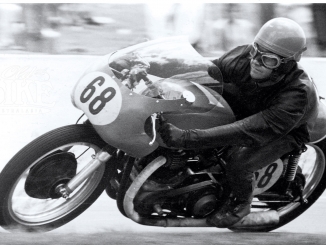

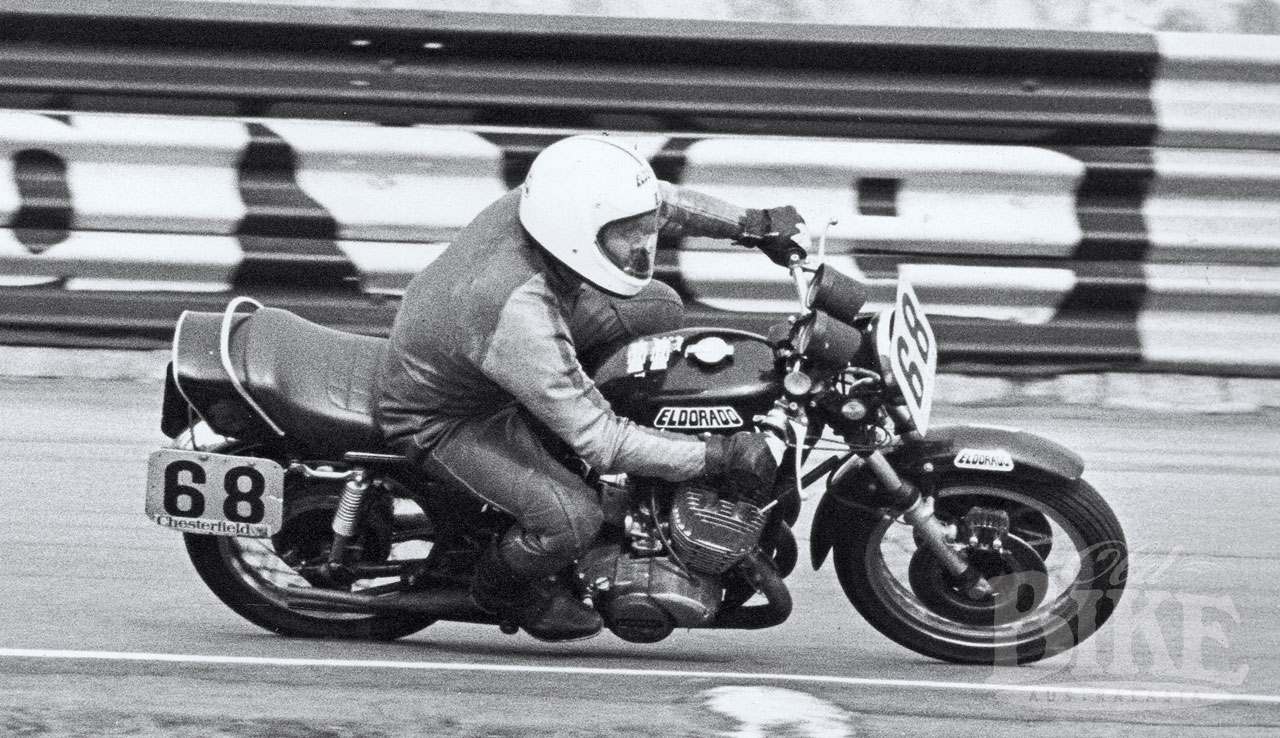

For the opening round on 10 February, 1974, 17 hopefuls faced the starter and from the moment the pack surged up the hill, Thomas and the Leo Pretty H2 were in control, although just inches in front of the Yoshimura Kawasaki 1000 ridden by Kiwi Mike Steele, with Warren Willing’s production trim (including standard silencers) H2 in third. Joe Eastmure’s modified T500 Suzuki twin headed the next bunch but the leading three held their positions to the end of the opening four lapper. Minutes later the second race was under way, and again Thomas called the shots from Willing and Ron Toombs’ 900 Kawasaki. Steele was determined to make the front running in leg three, but stepped off in the loop, folding up the front end of the Yoshimura Z900 and putting himself out of the remaining race. Just to rub it in, Thomas set a blistering 59.1 second lap in winning the final heat from Willing and Toombs, to end the day on maximum points. Thomas’ domination sent everyone away determined to sharpen up their act for the second round on March 31, but Garry and Leo Pretti were busy as well, and their H2 was an even quicker package than before.

Joe Eastmure’s 500 Suzuki, fettled by Alan Hales, had benefited from the break as well and was markedly quicker. This time it wasn’t Thomas that snatched the lead from the start, it was veteran Ron Toombs in the Z1 prepared by Neville Doyle, but it was still Garry’s black H2 at the head of the field after one lap, and the next time around be took half a second off his previous best time. Eastmure was flying as well, recording a lap of 58.6 second – faster than any Suzuki had ever been around Amaroo Park – and snatched second place after four frantic laps. Indeed, this set the pattern for the round, with Thomas first in all four and Eastmure with four seconds, while Willing and Toombs squabbled over third in each race. In the second leg, Thomas carved his time down to 58 seconds dead – just 0.7 seconds outside the outright lap record, and on a converted road bike.

The second half of the 1974 series saw a slight changing of the guard, with Thomas curbing his normal gusto to protect his healthy lead, and Warren Willing’s H2 now a serious threat with expansion chambers and conversion to methanol fuel. Murray Sayle was aboard the ex-Toombs Z1 and John Warrian had swapped his uncompetitive GT750 Suzuki for a 900 Kawasaki. At the sharp end, it was all Willing and Thomas, with Garry taking the first heat and warren the next three. Len Atlee’s chances evaporated in a bizarre accident when he collided with the travelling marshal, speedway star John Langfield. It was then a five month wait until the series finale on November 24, but Thomas’ confident took a dive when the H2 seized in practice, necessitating an overnight rebuild and an untried machine on the starting line for the rapid-fire four race format on Sunday. Garry may have been riding for points, but it didn’t seem so in the opening heat when he and Willing went at it hammer and tongs to set the scene for the day. In the end, they had two wins apiece, but Garry had done all he needed to wrap up the series and claim the biggest prizemoney of his career. “I never really won any money before,” he said some years later, “but this was really different. Most of the other prizemoney might have paid for a tyre or some fuel, but I could have bought a new TZ350 with the cheque this time!”

Formula for failure?

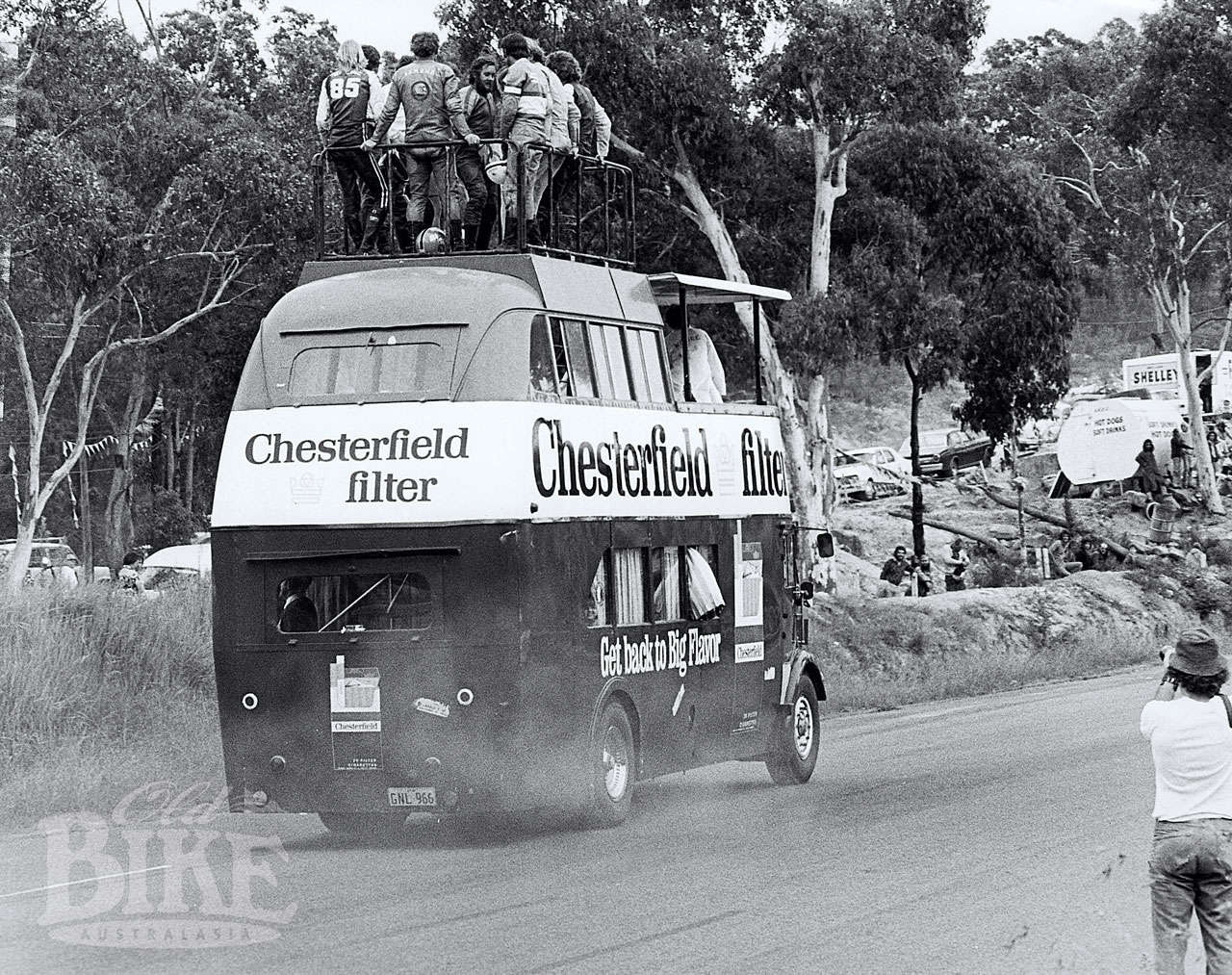

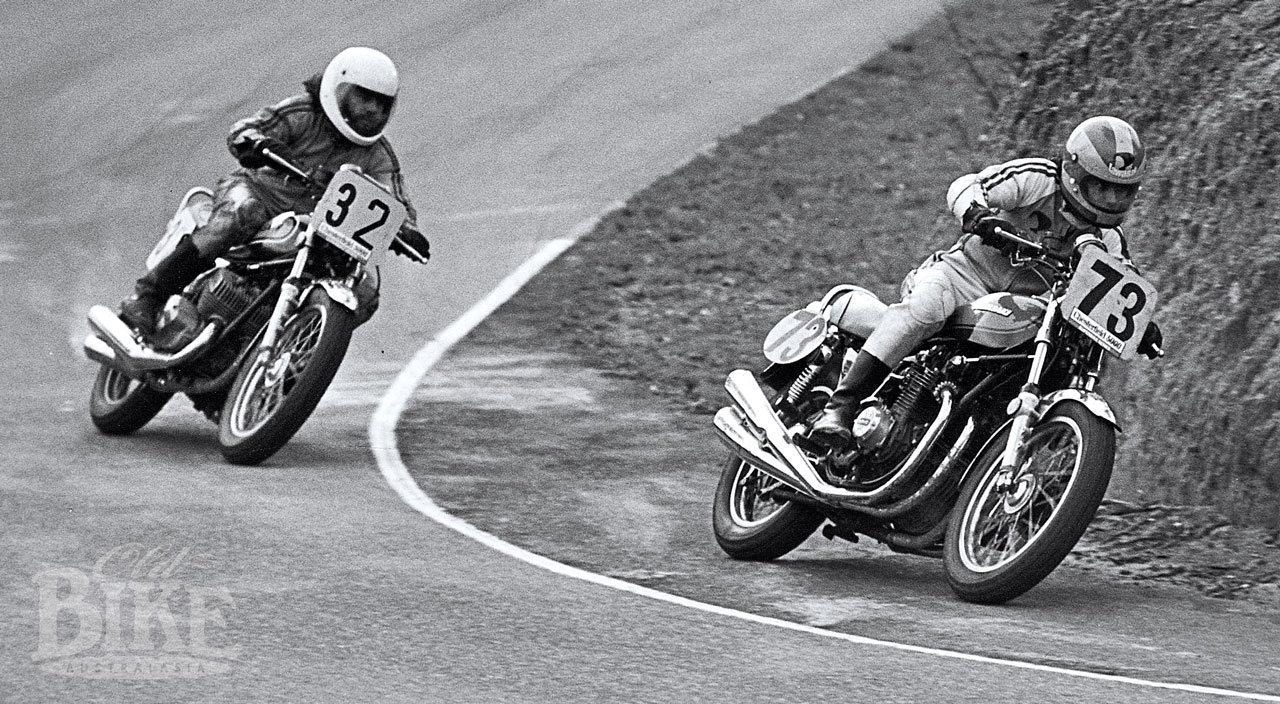

An outside event transpired to temporarily alter the face of the third (and last) Chesterfield Superbike Series in 1975. Warren Willing had his licence revoked following a scrutineering report from the 1974 Castrol Six Hour Race that found illegal modifications to the Adams Team Kawasaki H2. Warren’s co-rider Gregg Hansford was similarly convicted but later had his suspension overturned. Roger Heyes and Dennis Neill also copped a six months suspension for running an oversized fuel tank. With a stack of star riders apparently sidelined for the opening of the 1975 Chesterfield series, Willoughby MCC went into a huddle and came up with a cunning plan. A hastily-invoked new rule allowed for ‘team’ entries, and for the series opener at Amaroo on February 9, Gregg Hansford, deputised for his mate on Willing’s Levi Strauss Team H2, and duly took four wins from four starts. But it wasn’t easy – veteran Ron Toombs and Roger Heyes (who had his suspension time reduced following an appeal to the ACU), on 900 Kawasakis, harried Gregg on every lap in a display that had the crowds screaming for more. But the newly-introduced ‘substitution’ rule meant that the 40 points went to Willing’s Levis Team entry.

The whole face of the sport changed on the weekend of the second round in March. Willing crashed his Levis Yamaha TZ750 in practice and was lucky to escape with only a broken collarbone and toe after the bike covered its rider in fuel and burst into flames. Worse was to come when Toombs piled off the ‚ Team Kawasaki Australia H2R750 on Sunday, smashing his elbow and leading to his retirement from racing. For the Chesterfield series rounds, Jeff Sayle stepped into the seat on Willing’s H2, with Kenny Blake aboard the injured Roger Heyes’ Z1000. But it was a resurgent Garry Thomas who mastered the wet track, taking three wins, with Blake spoiling a clean sweep in the second of the four races.

June 29 saw the third round, where Thomas came out fighting to defeat Willing, at last back in the seat of his own entry. But the minute or so on the grid for heat two saw gremlins enter Thomas’ ignition system, and he could only splutter his way around as Willing blasted to victory in the next two races. Only four starters fronted for the final heat, where the four strokes finally prevailed providing a win for Clive Knight’s 750 Honda. The series ground to an ignominious conclusion in July, culminating in what Revs Motorcycle News described as “the failure of the Chesterfield Superbike Series.” Under the rules, the Willing/Hansford/Sayle squad had already tied up the series, but that didn’t stop Warren from strolling to four easy wins on his highly-developed H2. With only a change to slicks, Warren pushed Hansford’s factory H2R all the way in the main Unlimited race.

And that was it. The richest series in Australia died without so much as a passing sigh. Simply, the opposition show had become a lot better. This was the era of the rise of Team Kawasaki Australia, and of Gregg Hansford in particular. Matched against Willing and stars like John Woodley, Bill Horsman and Gregg’s own team mate Murray Sayle, the Unlimited class was where it’s at. Then there was the phenomenal growth in Production Racing which demanded rigidly standard bikes, with plenty of good-paying meetings in virtually all states. Few were willing to modify their production mounts, or build a special, for the Amaroo-only series.

The failure of the ‘Fag Drag’ (common pit-parlance for the Chesterfield Superbike Series) to draw big snorting four strokes also made it just another bunch of two strokes in a program already full of them. Ironically, it wasn’t too many years later when the Superbike concept was re-invented in Victoria, where the legendary racing between Andrew Johnson, Rob Phillis, Malcolm Campbell and many others mounted on fire-breathing four strokes, formed the foundation for the Australian Superbike Championship as we know it today.

And of course, the term ‘Superbike’ found its way into the international language of motorcycle racing, and into its own FIM World Championship. It had come a long way from the fly-blown confines of Amaroo Park and the rocket-fuelled imagination of cartoonist Peter Ledger and his super-heroes on super-bikes.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Michael Andrews, Jeff Nield, Allan Rooney.