In 2007 Ducati’s new 800cc desmosedici MotoGP racer, in the capable hands of young Casey Stoner, was the class of the grid, and its predecessor won the final race of the 990cc era ridden by Troy Bayliss, but the Ducati V4 story started 45 years previously, as Alan Cathcart relates.

At 20-year intervals over the past four decades, Ducati has flirted with the V4 concept, without until now ever adopting it wholeheartedly. Legendary Ducati progettista Fabio Taglioni produced as many as 1000 different engine designs during his 30-year reign as the company’s engineering guru from 1954 until 1984, and it was almost inevitable that sooner or later his creative c.v., ranging from the triple-camshaft desmodromic twins and singles which Ducati went Grand Prix racing with in the late ’50s, through to the 864cc V-twin desmos which were the pinnacle of his streetbike portfolio, would include a four-cylinder motor. In fact, there were three of these in all, the most recent being the stillborn Bipantah project terminated in 1982 on the eve of Taglioni’s retirement while the first was his only transverse in-line design, the four-cylinder 125cc GP contender which he created in 1964, but was never raced. Concurrent with this came undoubtedly the most famous of the trio – the Apollo 1260.

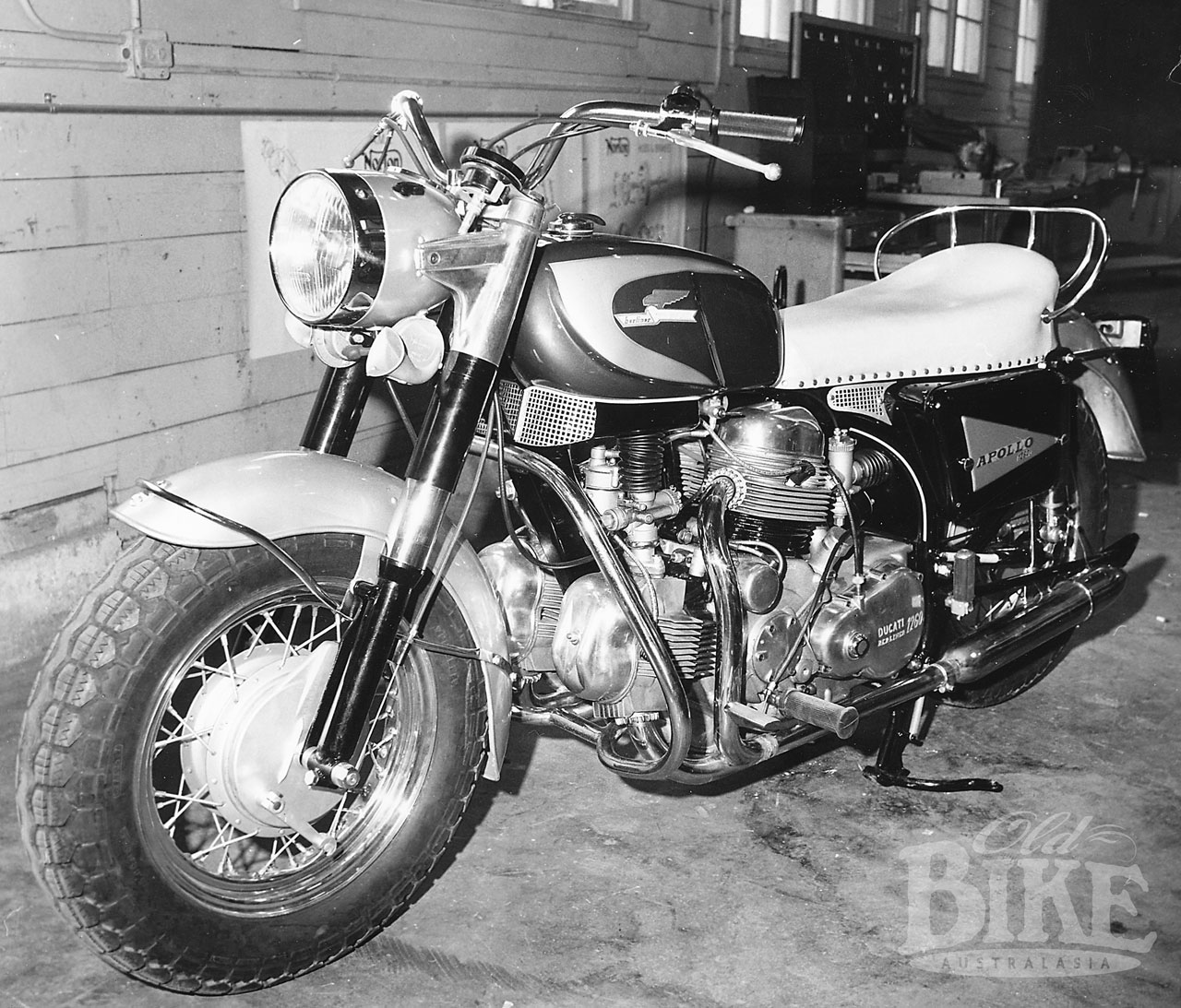

Few motorcycles ever built have enjoyed as mythical, as fabled, a reputation as Ducati’s legendary but abortive V4 Apollo project, the Italian marque’s failed attempt to produce a Harley-style cruiser aimed at the American market. As the largest motorcycle ever built by Ducati, it’s a critical component of the ducatista dogma, which because only two examples were ever built, has remained an enigma. But now, thanks to the generosity of the Japanese owner of the sole surviving known example of the two Apollo prototypes built back in 1963, this 1256cc behemoth is now on display in the factory museum in Bologna.

Back in the early ’60s, Ducati was one of dozens of relatively small Italian manufacturers, each struggling to overcome the savage attack on its crucial home market levelled after 1955 by the Fiat 500 minicar, which in its hundreds of thousands brought an end to the postwar boom in Italian biking. This collapse in sales not only forced first Gilera and Moto Guzzi, then a year later in 1958, Ducati, to withdraw from Grand Prix racing – a sure sign of distress in such a sport-mad country – but also to focus ever more closely on their export markets, and particularly the USA, then hungry for European products.

In Ducati’s case, with production declining to around 6000 bikes a year by 1960, and the company only kept afloat thanks to state subsidies forthcoming mainly thanks to Bologna’s status as the bastion of Italy’s powerful Communist party, this meant an ever greater dependence on the firm’s New Jersey-based US importer Berliner Motor Corporation, which after its appointment in 1957, by the early ’60s was selling no less than 85% of Ducati’s total production, meaning that brothers Joe and Mike Berliner effectively called the shots at the recession-hit company.

Elder brother Joe Berliner was convinced of the potential of the US police market, especially since American anti-trust legislation required that police departments across the country at least consider alternative sources of supply to the prevailing Harley monopoly, this now meant evaluating foreign products. However, official US police department specifications were increasingly standardised across the country, and naturally favoured the overweight, unsophisticated, large capacity home-grown product which Harley had been building since its earliest days, and specifically required an engine capacity of at least 1200cc., as well as a minimum 60-inch/1525mm wheelbase, and – worst of all – the use of 5.00 x 16 tyres: no others were acceptable.

Berliner was not easily daunted, and he contacted Ducati chief Dr.Giuseppe Montano to see if the firm was interested in producing a special machine for this significant market, even though the Italian company’s largest-capacity model in 1959, when Berliner first approached them, was the 200cc Elite. After considering the design of the archaic 74 cu.in. Harley which was then effectively standard issue to US police departments, Montano and Taglioni readily agreed – certain they could produce a more efficient and much more modern design which Berliner could sell at reasonable cost, even after payment of the quite steep US import duty. Taglioni eagerly accepted the commission as a technical challenge.

Montano encountered initial scepticism from the government bureaucrats in Rome who controlled the company’s finances, which meant negotiations dragged on for a couple of years. Eventually a deal was finally struck in 1961 resulting in a joint venture, whereby Berliner would underwrite the development costs of the new model, and the Apollo was the result – a name chosen by the Berliners to commemorate America’s manned space flights, which had recently begun. In return for their financial aid, Berliner Motor Corp. would be allowed to dictate its specifications, but would be expected to make a further contribution towards tooling costs, if the prototype reached production.

Apart from meeting the standardised US police regulations, the brothers‚ only stipulation was that the bike should have an engine bigger than anything in Harley’s range, then topped by the 74 cu.in./1215cc FL-series Duo Glide models. The remainder of the technical specification was left to Taglioni, who decided on a 90-degree V4 engine whose perfect primary balance meant no need for a counterbalancer to eliminate vibration, even with the 180-degree crank throws he opted for (each pair of pistons rising and falling together), and separate, differentially-finned, air-cooled cylinders – a design similar to the 250cc V4 he’d drawn up back in 1948 as his I.Mech.E degree project at Bologna University, but with pushrod ohv valvegear and a single gear-driven camshaft positioned between the cylinders, just as on the V8 car engines. The two valves per cylinder were operated via pushrods and rockers with screw-type adjusters, while the horizontally split wet sump engine featured a single crank running in a central support, with each pair of conrods sharing a single caged roller-bearing big end. Ignition came via a 12v battery under the seat, with four sets of contact breakers, two running off each end of the camshaft, and four coils feeding the 14mm sparkplugs, one per cylinder. Taglioni had considered watercooling the engine, but rejected this on the grounds of complication and bulk, and likewise politely turned down Joe Berliner’s suggestion to incorporate shaft drive, which he mistrusted, in favour of a duplex chain final drive. However, he did make space in the housing containing the Apollo’s five-speed gearbox and gear primary drive to accept a Sachs variable-speed automatic transmission at a later date.

With the front cylinders of the mighty 1256cc engine lifted 10 degrees from horizontal to improve cooling to the rear pair, and measuring an even by today’s standards ultra short-stroke 84.5 x 56 mm, the Apollo’s V4 motor was by some way the most oversquare design Taglioni had ever produced for Ducati. This was installed as a stressed member in a beefy-looking open-cradle duplex chassis with a central box-section downtube between the front two cylinders, and with specially developed Ceriani suspension, the Apollo’s handling was certain to outperform Harley, who had only recently discovered rear suspension, though the full-width 220mm single-leading shoe brakes front and rear didn’t promise as much. A kickstart was provided for the brave to use, while for mere mortals a Marelli electric starter similar to the one used on a Fiat TV1100 car, was also featured. A massive 200W generator was fitted on the right, opposite the seven-plate oil-bath clutch, in order to cope with the additional load imposed by various police paraphernalia such as sirens, lights and radios.

Relatively compact in spite of its architecture, at just 450mm wide, the all-alloy V4 engine allowed the Italian bike to compare favourably with its Harley rival, scaling 271 kg. dry with a 1555mm wheelbase, against the American V-twin’s 1580mm stance and 291 kg. weight. So, even though Ducati test rider Franco Farne came back from an early test run aboard the Apollo complaining that ‘it handles like a truck’, this was strictly The American Way, and the Ducati Berliner 1260 Apollo‚ as the bike was officially known, made up for this with its straight-line performance, delivering a claimed 100 bhp at 7000 rpm (against 55 bhp for the Harley Wide Glide), running on four 32mm Dell‚Orto SS carbs and 10:1 compression, and good for a top speed in excess of 200 kph – so, more than 120 mph. Pretty impressive for the day – as befitted what was in prototype form the largest capacity and most powerful motorcycle yet constructed in postwar Europe. But also damning – for its meaty performance was also the Apollo’s downfall, a fact confirmed by Ducati tester and former GP mechanic Giancarlo Fuzzi‚ Librenti, who was the first to suffer the heart-stopping experience of having the rear specially-made 16-inch whitewall Pirelli throw its tread at high speed on the Milan-Bologna autostrada, after balooning under sustained 100 mph speeds and detaching from the rim.

The agreement had called for Ducati to construct two complete prototypes and two spare engines, and the first of these, very evidently a Latin pastiche of an American motorcycle, painted in a ritzy metallic gold paint job and complete with huge cowboy saddle fitted with a chrome grab handle – all that was missing were the tassels and fringes – was handed over to the Americans in a formal ceremony in March 1964. High-rise ape-hanger‚ handlebars, deeply valanced mudguards, a semi-peanut fuel tank seemingly highjacked from Ducati’s 175cc production line, and fat whitewall tyres specially built by Pirelli, completed the Italo-American styling, whose effect was so heavy (not improved by the fat, car-section tyres) that the Apollo looked much bigger and bulkier than it really was. A second prototype built later, was displayed at the Daytona Show in Cycle Week 1965 and looked more tasteful, with leaner mudguards, altered sidecovers, and painted in a more discreet black and silver – albeit still with the Wild West seat.

However, while initial tests proved the Apollo to have an abundance of power, it was soon discovered that the V4 engine was too potent for the 16-inch Pirelli tyres, even in the softer state of tune developed alongside the so-called 100-bhp ‘Sport’. Ducati and Berliner had always intended that the police Apollo should form the basis of a line of freeway cruisers, which would provide an additional means of recouping the outlay spent on development. The prototype engines therefore had two specifications – the 100 bhp Sport version and a ‘normale’ alternative employing a softer cam, 8:1 compression and a single 24mm Dell‚Orto for each pair of cylinders, front and rear. This produced 80 bhp at 6000 rpm – but still the tyre problems persisted, and had now spread to America, whence alarming stories came filtering back of test riders nearly killed in high-speed testing on banked ovals and freeway straightaways. The solution was to detune the twin-carb version of the engine yet further, reducing the compression still more to 7:1 and installing even softer cams. This lowered the power to 65 bhp, still adequate to meet police performance specifications, and superior to the Harley, thanks to the V4 Ducati’s lighter weight, and appeared to finally resolve the tyre problem.

But this step effectively ruled out the Apollo being sold as a luxury sports tourer, since its power-to-weight ratio was now inferior to the BMW and British twins which would have been its ‘import’ rivals in the US market. Berliner had been so confident of the bike’s potential that he’d already begun marketing the Apollo in the States, and had printed a brochure quoting a price of $1500 for the touring version and $1800 for the Sport – substantially more than its European twin-cylinder competition, and double the cost of the equivalent Harley. At that price level, the Ducati would have had to boast an additional edge in performance to justify the extra cost, but in detuned form, it could not. With the V4 set up to deliver the right kind of power to meet the demands of the marketplace – power that it was capable of – it would be lethal until tyre technology caught up with it.

This situation provided the perfect opportunity for the Christian Democrat government- controlled bureaucrats in Rome to kill off a project they’d never had much faith in, and which emanated from a city controlled by their bitter Communist rivals, citing as an excuse the fact that with the model now suitable only for the specialist police market, its sales would be insufficient to justify the immense tooling costs involved in gearing up the Ducati factory for its production. Berliner, who had already successfully demonstrated the Apollo to selected police chiefs, was appalled. He had promised that production of the reduced-power version would commence in 1965, yet now the whole project seemed in danger of collapse.

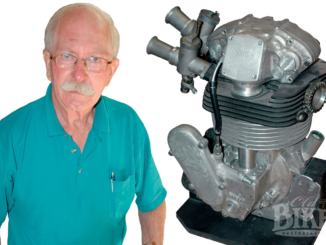

So it proved. Further funding for the Apollo was withdrawn, and Montano was reluctantly forced to cancel the project early in 1965, leaving the second of the two prototypes constructed to head straight back from Daytona into the Berliner warehouse at Hasbrouck Heights, N.J., where it remained for the next two decades in a corner of the storeroom – a sad reminder of a motorcycle killed off by a mixture of government infighting and its own advanced specification. The Apollo was just too much, too soon. As an indication of how proud he was of the design, though, the spare engine sat on display in Taglioni’s office for 20 years until his retirement, a silent testament to his versatility and farsightedness.

However, the memory of the Apollo lingered on, for as a prophetic article in Italy’s Motociclismo magazine had suggested when the existence of the Apollo was first revealed in 1963, one half of the engine would, and did, provide a superb basis for a range of 90-degree V-twin models. Five years after the project’s demise, Taglioni proved the worth of that assertion when he designed Ducati’s first ohc 750 V-twin, closely inspired by the Apollo’s architecture. 30 years on, Ducati has been paid the ultimate accolade by having its trademark technical format copied by Honda, and Suzuki. But the Apollo was the inspiration for this idea, and now it’s the turn of the MotoGP desmosedici racer to prove the worth of the V4 concept in full – and in so doing, to sire the range of Ducati V4 streetbikes we all know is coming further down the road. Wonder if one of them will be called an Apollo?

Riding Ducati’s dinosaur

Mysterious and monolithic, Ducati’s abortive V4 Apollo has always had one big question hanging over it: what’s it really like to ride? Because of safety concerns thanks to the tyre problems of 40 years ago, no journalist was ever allowed to test it back then – and until the generosity of Hiroaki Iwashita brought the sole surviving example back into the public domain via his considerate decision to loan it to the factory museum on an extended basis, Ducati’s dinosaur was a two-wheeled fossil, set in stone.

Iwashita-san acquired the Daytona showbike, second of the two Apollos built (the whereabouts of the original metallic gold example are unknown, if indeed it still survives) in 1986 from Cincinnati-based DomiRacer Inc., then America’s largest vintage parts specialist whose owner Bob Schanz had acquired the contents of the Berliner warehouse when the company finally closed down two years earlier. Among the many Ducati artefacts was the Apollo prototype, “somewhat neglected and shop worn, but missing only the original (fuel) tank”. Iwashita-san bought the bike from DomiRacer in 1986 for $17,000 – big money, back then – and secreted for the next decade in his private collection in Japan until 1995, when he displayed it at a vintage bike show in Tokyo. This alerted Ducati to the bike’s existence, and when the factory museum was established in the wake of the TPG takeover at the end of ’96, in due course it became a centrepiece exhibit on what will hopefully be an extended loan.

Actually, while the pair of white-walled 16-inch Goodyears the Apollo wears today are the same type as those on the bike when it appeared at Daytona 40 years back, at least they’re freshly-fitted new-old stock, so quite adequate for a gentle cruise in which the headlamp- mounted Jaeger speedo’s needle didn’t once pass the 70 mph mark – yes, miles not kilometres, inevitably reflecting the market it was built for. At just 760mm/29.5 in. high the relatively plush seat is low enough to throw a leg over easily, and once astride the Apollo you’re immediately surprised how low-slung and slim it feels. The high, pulled-back handlebar is very ’60s, very US of A, though not as exaggerated as on some later Harleys, and combined with the well placed footrests which aren’t nearly as far forward as on many modern cruisers, delivers a surprisingly comfy riding stance which doesn’t become a problem at speed, in spite of the high bars – you don’t feel you have to hang on too tight, and there’s no instability at speed as a result. Just chill out and cruise….

The four Dell’Orto racing carbs which the Apollo currently wears (and which presumably therefore indicate that this bike has the most powerful state of tune, not the restricted twin-carb spec) scorn the use of a choke, but on a warm Italian day the motor catches quite quickly, then settles down to a quite fast idle – no revcounter fitted, of course, but it sounds around 1500 rpm – with an unmistakeable lilt more like an American V8, than an Italian four-cylinder minicar. The Apollo’s exhaust note is absolutely unique, quite unlike any V4 Honda, and quite loud, too – the slender twin Silentium silencers don’t have a lot of packing in them.

Time to motor, and lifting my right toe to engage bottom gear on the one-up/four-down right-foot gearchange with its extremely long lever throw, I was impressed how smoothly the Apollo took off from rest, until the time came to change gear from the long first, up into second. That’s when the age and nature of Ducati’s V4 cruiser comes to your attention, because even swapping gears in the higher ratios without having to go through neutral is a very slow, measured process. Rush it, and for sure you‚ll get a false neutral. However, once it goes in, the Apollo drives forward eagerly with a very long-legged feel, especially in the intermediate gears – there’s great response from the light-action throttle, and frankly there’s no way this engine feels like a child of the ’60s, more like 15 years later. Top (fifth) gear feels like an overdrive, so would have been ideal for cruising the freeways then starting to proliferate throughout mid-‚60s America as part of the Interstate Freeway Expansion Program. There’s enough midrange pickup from the meaty 1256cc engine to use the bottom four ratios just as a means of getting into top, and then leaving it there, surfing the rich waves of torque available at almost any revs.

Yet the Apollo’s undoubtedly impressive engine stats are delivered with a smooth panache completely at odds with its ’60s genesis. Compared to a British twin of the pre-Isolastic era, or any Harley ever made, it’s like setting a sewing machine against a concrete mixer in terms of vibration and riding comfort, only a BMW Boxer of the era delivering anything like the same smoothness at any revs as the Apollo. At a time when there were no four-cylinder motorcycles of any type on the market, the Apollo would have set a standard of performance and rider comfort that even a decade later would set the benchmark for the Japanese to aim at. This was truly a bike ahead of its time, replete with avantgarde engineering.

The Apollo’s handling is frankly adequate rather than exceptional, even by the standards of the era, and the culprits are the US police department regulations which imposed the use of those 16-inch tyres on a bike crying out for the 18-inch sports rubber then being introduced in the mid-‚60s. Even without the safety considerations which led to the bike’s demise, the dynamic limitations of the car-type four-ply Goodyear covers handicap the Apollo’s handling potential irredeemably. They look and feel completely unsuitable for anything more than about 15 degrees of lean, and though it’s possible to deck the footrests very easily without too much of a sense of insecurity, you can feel the tread start to move about under you if you start asking too much of the tyres round turns. The long wheelbase certainly makes it handle like a truck in tight corners but the payoff is good stability round fast sweepers, where the surprisingly effective Ceriani suspension felt pretty good by the standards of 40 years ago. And the very springy seat helped soak up any shocks that got past the twin rear shocks.

Really, the only thing on the Apollo apart from the heavy steering and those ludicruous tyres which gave serious cause from concern were the brakes. While the matched pair of 220mm single leading-shoe drums front and rear are adequate at slow speeds, they fade badly after a couple of hard stops, sending the lever back to the bar and making the rear brake pedal all loose and floppy. OK, by the standards of the era they were probably the industry average – but with the performance delivered by that fantastic engine, the tyres weren’t the only thing that needed attention, just the one that brought an end to the project, full stop.

And that was literally a two-wheeled tragedy, because the inability of the tyre companies to come up with a product capable of harnessing the performance delivered by such a big-engined, heavy bike, deprived ’60s bikers of the thrills and satisfaction of riding the first of the next generation of four-cylinder sportbikes. For although Joe Berliner had the right idea in commissioning the Apollo from Ducati back in 1961, it was for what turned out to be the wrong reasons. If he hadn’t quite naturally focused on the US P.D. market with its insistence on 16-inch rubber, but had conceived the Apollo as the world’s first four-cylinder sportbike with tyres and handling to match, even (especially?) at the higher price that the Italian V4 would have dictated compared to the Triumph Bonneville that became the benchmark sportbike of the 1960s, the US market – and those of us in Europe – wouldn’t have had to wait another ten years for Kawasaki to do the job properly with the arrival of the Z-1, in the wake of the CB750 Honda. After riding it I‚m convinced that the Ducati Apollo was one of the great missed opportunities of world biking.

Story: Alan Cathcart Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura (statics) and Kel Edge (action)