From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 75 – first published in 2018.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Jim Scaysbrook

With a runaway success like the four-cylinder Z1/Z900, plus the soon-to be released fours in the shape of the Z650 and Z1000, why would Kawasaki bother with a 750cc twin?

The question was especially poignant with the recent demise of the troubled TX750 Yamaha twin, although Yamaha did soldier on with its now-venerable XS650 twin. The British parallel twin pretenders had largely vanished; the Enfield Interceptor, BSA’s A65, both gone, and the Norton Commando about to do the same, leaving only the 750cc Triumph Bonneville, of which the less said, the better. Perhaps Kawasaki felt that the once-proud class was ripe for picking, and that big-twin fans needed looking after. It’s true that the new breed of four-cylinder bikes – soon referred to as UJM (Universal Japanese Motorcycles) – did not have across-the-board appeal; many felt that the complexity and the loss of do-it-yourself maintenance was a backward step.

Of course, Kawasaki had built a big twin before, or rather, they had inherited the BSA-like W1 650 as a result of their takeover of Meguro in 1964. Very British in concept and styling, the 650, through subsequent W2 and W3 versions, remained in production until 1975, by which time 26,289 had been built. So there was a gap in the range that the Big K wished to fill, but what resulted owed nothing to the W range. In fact, the genesis for the new 750 came in the form of the Z400, a popular seller from the point of its release in 1974, and which was marketed as the “little brother” of the four-cylinder Z1, at half the price.

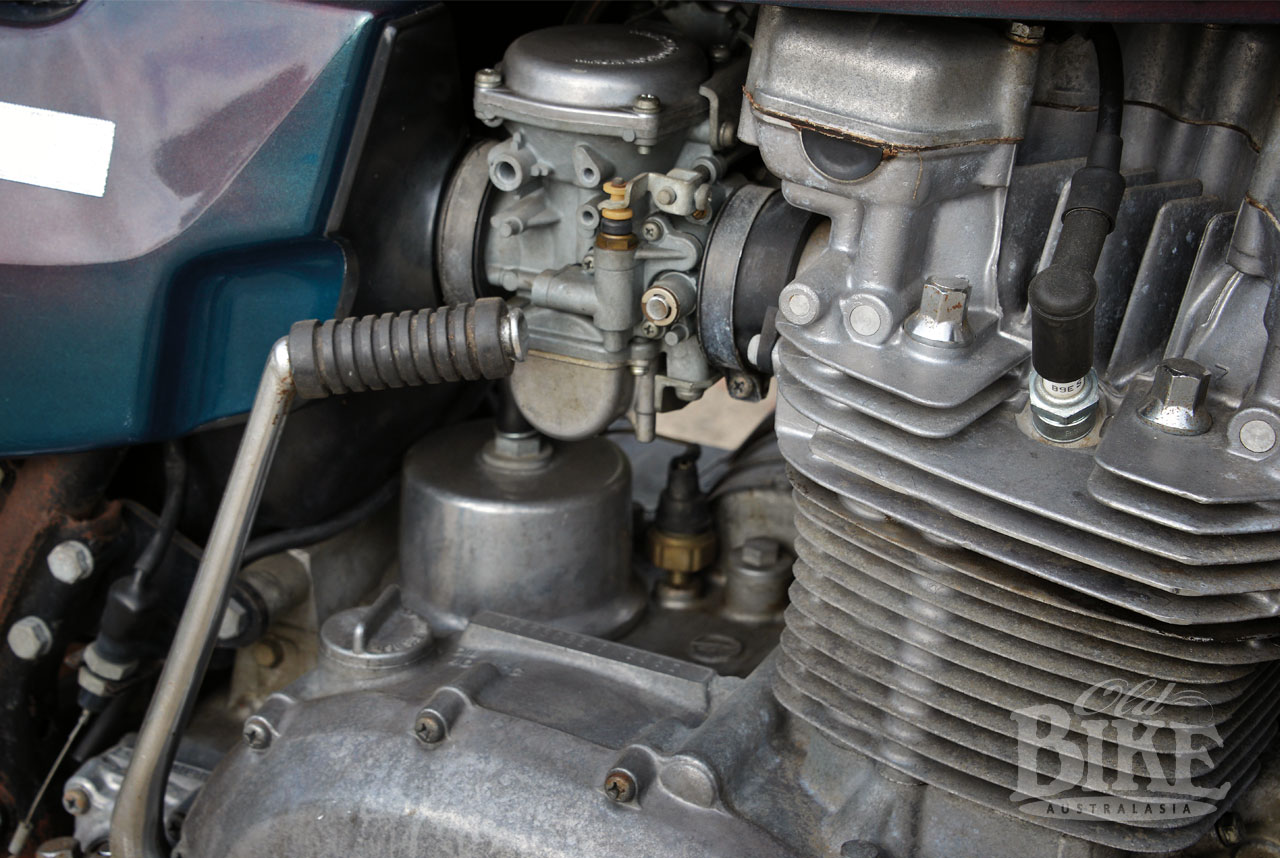

The new KZ750 actually made its world debut at the 1975 Motorcycle Show at Earls Court, London. Released for sale in 1976, the KZ750 (also known as the Z750 in some markets but never released in Australia) was all-new, although the cylinder head design did mirror the thinking in the Z1. Double overhead camshafts (unlike the smaller Z400 twin which used a single overhead camshaft) operated the valves via shim and bucket adjustment, with chain drive to the cams. However downstairs, things were entirely different. Here lay a truly massive crankshaft supported by four main bearings. The 360-degree throws had the pistons rising and falling together, with firing taking place on alternate strokes. Instead of the roller bearing bottom end on the Z1, the new twin used slipper bearings for the big ends, with a Morse Hy-Vo (High Velocity) primary chain on the right side of the crankshaft connecting the five-speed transmission. On the left side of the crankshaft sat a three-phase Nippon Denso generator.

And then there was the vexed question of vibration to address, as with all vertical twins. Kawasaki’s solution was a pair of counter-rotating dynamic balancers, or bob weights – one at the front of the engine and the other behind it – chain-driven from the crankshaft. The weights each had one half of the centrifugal force of the crankshaft counterweights, and since the direction of these forces are opposite, they cancel each other out. All of which went some way, but not the whole way, towards solving the problem. Although vibration levels were deemed acceptable, the KZ750 did still have its tingles below 4,000 rpm, while by the time the red line was approached, things were a little more animated. Still, vibration of sorts is part of the appeal of big twins, or so the legend goes.

The engine unit was housed in a very robust-looking full double cradle frame which included large tubular brackets from which to mount the exhaust system, while suspension at both ends followed tried and proven lines. There were quirks, of course, such as the barrel lock attached to the left side of the handlebars, with the sole purpose of securing a helmet – a feature which disappeared on later models.

Everything about the styling was conventional, with the fuel tank seemingly (but not) plucked straight from the Z900, and a similar duck tail treatment for the rear of the seat. The robust chromed steel mudguards also closely resembled those of the bigger four-cylinder model. Very substantial looking mufflers did a very substantial job of muting the exhaust note, which did not please the purists – after all, a throaty exhaust note was part and parcel of the old package. However Kawasaki, and others, now had ever-stricter emission laws to deal with, hence the exhaust design and the use of Constant Velocity carburettors. Another innovation aimed at minimising pollution was what Kawasaki called Positive Crankcase Ventilation, which had been pioneered on the Z1 and was designed to recycle blow-by gas from the crankcase through the carburettors. The new 750 also scored top marks in fuel consumption, achieving around 53 miles per gallon in some tests that even included runs on drag strips as well as high-speed freeway work. In accordance with its design ethos, the KZ750 was the epitome of reliability, with long service intervals and a frugal appetite for parts.

One year after its introduction the 750 went through minor revisions, mainly aimed at reducing vibration and making the bike a more pleasurable experience around town. One of the main criticisms was backlash in the transmission, which affected both acceleration and deceleration and gave a rather snatchy ride in traffic. The generally unloved CV carbs, which were supposed to supply exactly the right amount of fuel at any given engine speed, and avoid wasting fuel at low speed, added to this twitchiness around town, being extremely sensitive to small throttle openings and making things quite exciting when the rider was trying to thread through corners. This was never completely cured and many felt that the bike itself could have been transformed with different carbs, along the lines of the Dell’Ortos with accelerator pumps. The KZ750 was the first Kawasaki to be sold with disc brakes front and rear, but the brakes, single discs front and rear, while powerful enough, became notorious for squealing; a very annoying trait. There were few complaints however, about the power, which came surging through from low revs just like a big twin should.

There was no getting away from the fact that this was a heavy bike, and this played havoc with the suspension, particularly the rear, which surrendered easily. It was also fairly bland looking, as were many Kawasakis of the time, with unimaginative décor and subtle striping. Gradually, the twin found its niche as a straight-forward, easily maintained and economical mount, and for several years was one of Kawasaki’s four-best selling models in the US. It was also cheaper than the four-cylinder Suzuki GS750. Subtle refinements occurred year by year, but by 1983 Kawasaki pulled the plug. It is difficult to ascertain just how many KZ750s were made, but the model did run for eight years, so there must have been quite a few, but you’ll be hard-pressed to find one today.

Our thanks to Classic Style at Seaford Victoria for the opportunity to photograph this very original US-import 1976 model, which had just 6500 miles on the odometer.

Specifications: 1976 Kawasaki KZ750

Engine: DOHC twin cylinder, 2 valves per cylinder.

Bore x stroke: 78mm x 78mm

Capacity: 745cc

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Lubrication: Wet sump.

Power: 55hp at 7,000 rpm.

Torque: 60.8 Nm at 3,000 rpm.

Carburation: 2 x 38mm Mikuni

Starting: Electric or kick.

Frame: Tubular steel, double cradle

Brakes: Front: single 295mm disc Rear: single 275mm disc

Tyres: Front: 3.25H-19 Rear: 4.00H-19

Weight: 224.5kg (dry)

Wheelbase: 1438mm

Fuel capacity: 14.5 litres