From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 66 – first published in 2017.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Sue Scaysbrook

A rare survivor from the initial production run of one of the world’s iconic sports machines.

“Half a point!” That’s all that separated Elvis Centofanti from the winner’s trophy at Motoclassica 2016 in the 90 Years of Ducati division. “Mind you,” says Elvis Centofanti, owner of the 750 Sport featured here, “when I saw the bike that ultimately won the prize (Paul Cowan’s 1968 350 Desmo), I knew I was in trouble. That bike is perfect.” Well, perfect it may be, but Elvis’ 750 can’t be far behind, at least to my eye.

But let’s start at the beginning – the beginning of the 750 Sport model, that is. The concept of doubling up a successful single cylinder engine to create a twin is nothing new, but Ducati’s fabled engineer Fabio Taglioni had his own ideas on how it should be done. However, despite his best intentions, Taglioni was forced to work within the severe restraints of Ducati’s parlous financial situation at the time. The problems were manifold. Without a large capacity model to supplement the singles, the company had no future, but it also had no cash, having dumped a considerable wad on the un-loved parallel twins at the behest of the US importer Berliner. Then in 1969, Ducati came under state control, with a subsequent vitally-needed injection of funds, as part of the nationalised EFIM (Investment and Financing for Manufacturing Industry) group. But it was far from a bucketload of cash, and Taglioni had to produce a design that was cost-effective as well as practical – and one with the necessary kudos to combat the rising threat in the big bike market from Japan and even what remained of the British manufacturing industry.

As we now know, his 90-degree ‘L Twin’ ticked the box on all counts. The new twin, initially released as the GT750, was essentially two bevel-drive 350cc single top ends on a common crankcase. Taglioni was an unashamed fan of the 120-degree v-twin Moto Guzzi that had enjoyed a lengthy spell as a competitive Grand Prix machine both pre and post war, and the new Ducati was certainly a masterpiece in practical engineering and it unquestionably looked the goods. The standard 350 bore and stroke of 76mm x 75mm was slightly altered to 80 x 74.4, but the heads followed the factory’s time-honoured tradition with single overhead camshafts driven by helical-cut bevel gears driven by shafts. The camshafts were suspended on ball bearings, with replaceable shims on top of each valve stems, as on the 250cc Mach 3 model. Unlike the singles which used hairpin valve springs, the 750 used coil springs.

Taglioni favoured this layout since it produced only minimal vibration through a near-perfect primary balance, and the lay-down front cylinder provided a steady flow of cooling air to the almost upright rear cylinder – always a bugbear with conventional v-twins. Downstairs in the vertically-split crankcases, the front, almost horizontal cylinder was offset to the left from the rear cylinder, with a pressed-up crank assembly with the one-piece conrods on caged roller big ends. The crank assembly sat on hefty ball bearings, with a helically-cut primary gear on the left side transmitting power to a wet clutch and the five-speed transmission. On the right side, sits the 150-watt generator and a vane-type oil pump – the pump driven by an idler gear which meshes with a spur gear on the right side of the crankshaft. The wet sump contained 4.5 litres of oil and meant there were no outside hoses or oil tank, and theoretically at least, no oil leaks.

The GT750 (or at least, a substantially finished mock up) was first seen in public at the Olympia Show in London in January 1971, followed by the Turin Exhibition one month later, and testing continued over the European summer. By the time the Milan Show rolled around in November, production was set to go, but in one respect the showroom model differed from the prototype, in that it had a frame based on the racing 500cc version (ridden in 1971 by Bruno Spaggiari and Phil Read) that had been designed and built by Colin Seeley. The production chassis was made from seamless, chrome molybdenum steel tubing, with the rear members providing the mounting bosses for the swinging arm rear suspension. To increase rigidity in the swinging arm, the rear chain adjusters ran inside the tube itself, which was the usual Seeley practice.

A fundamental issue with the so-called L-twin design was an inherently long wheelbase, due partially to the need for clearance between the front cylinder head and the front wheel. To minimise this, Taglioni mounted the gearbox mainshaft and layshafts on top of each other, with a set of helical gears coupling the mainshaft to the crank. The bespoke 38mm Marzocchi forks featured motocross-style ‘forward axle’ mounting, combined with a 19-inch front wheel, which gave the GT a raked-out, rangy look. The resulting 1562mm wheelbase was still on the long side, but the best that could be achieved under the circumstances.

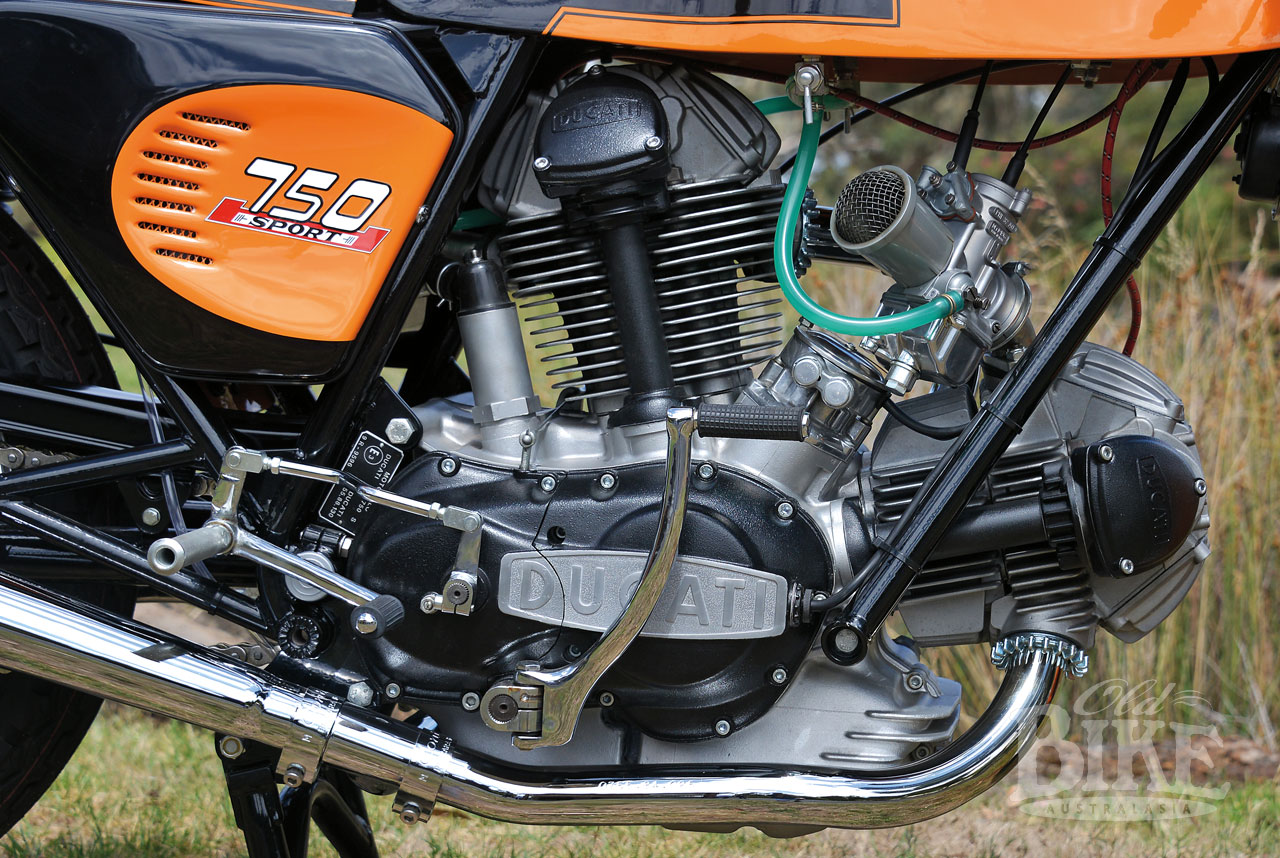

Famously, the new Ducati 750 (in desmo form) had a dream debut by scoring a 1-2 at the Imola 200 in April 1972, ridden by Paul Smart and Spaggiari – a result that was priceless in terms of publicity. To cash in, Ducati had a logical variant of the GT750 ready to roll – the 750 Sport. Finished in a vivid shade of vermillion yellow, the Sport had a black zig-zag stripe on the fibreglass fuel tank which was subsequently, but unofficially referred to as the Z-stripe model. To further differentiate the Sport from the GT, black painted engine covers, bevel shafts and top covers were used, with black-painted sliders on the leading-axle Marzocchi forks. A single racing-style seat was employed with no concession to two-up riding. Clip-on handlebars, high-mounted twin Veglia instruments, rear set footrests/gear lever and rear brake pedal added to the sporty style. Inside the engine was a lightened crankshaft, and higher compression 9.3:1 pistons. Unlike the GT750, which initially used Spanish Amal carburettors before switching to Dell’Ortos, the Sport employed larger 32mm Dell’Orto PHF32A carburettors. Power was officially quoted at 62hp at 8,200 rpm.

The black engine distinguishes the original Sport, as subsequent models in 1974 had polished aluminium side covers. As on the GT750, a Lockheed disc brake and master cylinder was initially fitted at the front with a Grimeca drum at the rear. A Scarab brake replaced the Lockheed in fairly short order, but were soon criticised for their tendency to corrode internally and occasionally lock up. For the 1973 750 Sport production year, the rear sub frame was narrowed and new Marzocchi shocks fitted. The fuel tank was also modified, tapering to the rear to fit the new frame configuration, while the ‘Z stripe’ disappeared in favour of a single black stripe, while the black section of the side covers also went in favour of an all-yellow finish. 1974 marked the final production year for the ‘round case’ engines, being replaced with the ‘square case’ design that first appeared on the 860 GT. For this year, the 750 Sport gained newly-profiled camshafts and a steel fuel tank, and towards the end of the production year the forward axle fork gave way to a centre axle style, although curiously using the same triple clamps which resulted in a completely different steering geometry. Brembo brakes also began to replace the un-loved Scarabs and some 1974 models used Ceriani forks.

The 750 Sport came to an end when the new 750SS appeared for 1975, but there is no doubt that the Sport created legions of Ducati followers and is one of the most significant models in the company’s history. Sure, it had its foibles, such as slightly dodgy electrics, but by and large this iconic motorcycle has stood the test of time and is rightly regarded as a modern classic, with Latin flair that gradually diminished on later bikes.

The owner’s view

This is a much-travelled machine. Originally shipped from the Bologna factory to South Africa, the 750 Sport now owned by Elvis Centofanti ended up in country South Australia, where it underwent a four-year restoration. “As I understand it, the 1972 production run were all ‘Z Stripe” models like this one, which was produced in June of that year, while the 1973 models had a stripe in the middle of the tank. I bought it on Queens Birthday weekend 2016. I think it rides beautifully. Even though people say they are uncomfortable, I don’t find this at all once you get going. It wants to lean into corners, and the engine likes to rev. The gearbox changes nicely, overall I am very impressed with the ride. Despite the rear brake feeling a little spongy, the brakes feel strong and responsive. You need to use both brakes to really pull it up. The Ducati register says that there were 735 750 Sports built in the production run, and only one came to Australia in 1972.”

Although a philosophical at coming second at Motoclassica in 2016, Elvis has rectified the few minor points that stood between him and the trophy. The 750 Sport now shares its stable with another immaculate Italian classic, a Laverda 1000C.

In the saddle

Having raced both the 750SS and the 900SS extensively, the 750 Sport had a familiar feeling. And yet, different. For a start, there’s no bikini fairing shrouding the front end; just a tidy cluster of instruments, and the road ahead. And although the dimensions are essentially the same as the SS model, the Sport feels smaller – the narrower fuel tank adds to this impression. One quirk of the design lies in the front end. Early models like this one used the motocross-style leading axle front forks, whereas the SS and even some Sport models used centre-axle forks, but both used the same steering yokes. So the trail must be different, as the frame and steering head are identical in both cases. So which is correct? The leading axle forks, with the extra trail, effectively lengthen the wheelbase and make the steering heavier, and with a motorcycle such as the Sport, with its inherently long wheelbase due to the need to clear the front cylinder head, the problem would seem to be exacerbated. Maybe that’s why the later models dispensed with the leading axle in pursuit of a shorter wheelbase and less trail. The Sport also has a 19 inch front wheel with a fairly thin tyre, whereas the SS models had 18s. In any case, it doesn’t much matter once you’re under way, except that you really need to anticipate corners and get set up for them, as the steering is definitely on the lazy side.

The riding position however, is perfect for the Sport’s area of expertise; that is, having fun through quick corners. The handlebars, although clip-ons, are set high and are fairly flat, which makes it easier on one’s shoulders and back. There’s plenty of room on the seat (you won’t be carrying a passenger) so you can move around at will – for a sporting bike, this one is pretty comfortable. Just settle in and listen to the music from the Conti megaphones.

Specifications: 1972 Ducati 750 Sport.=

Engine: 90º L-twin, SOHC 2 valves per cylinder, bevel-driven camshafts.

Capacity: 748cc.

Bore x stroke: 80 x 74.4 mm

Compression ratio: 9.3:1

Induction: 2 x Dell’Orto PHF 32A carburettors.

Ignition: coil and battery.

Starting: kick

Power: 62hp and 8,200 rpm.

Transmission: 5 speed with wet multiplate clutch.

Frame: Tubular steel trellis.

Front suspension: 38mm Marzocchi telescopic forks.

Front brake: 275mm single disc with Lockheed caliper

Rear brake: 200mm Grimeca drum.

Front tyre: 3.25 x 19

Rear tyre: 3.50 x 18

Wheelbase: 1530mm

Seat height: 780mm

Dry weight: 182 kg

Fuel capacity: 17 litres

Top speed: 210 km/h