Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

To own an FB Mondial in 1950 would be akin to having Jack Miller’s 2014 Moto 3 KTM in your garage today. Because this relatively tiny Italian marque totally dominated the first three years of the 125cc World Championship, from 1949 to 1951, beating the might of MV Agusta and Moto Morini in the process.

Mind you, those Grand Prix racers were a fair degree removed from the consumer models, but the quality, the sophisticated engineering, the innovation and the superb finish were certainly present in every model sold to the public. Should one be lucky enough to purchase one of these superb machines, you were part of a very exclusive club indeed.

The company itself began when Giuseppe Boselli and his three elder brothers – all of Italian nobility – formed the F.B. company (Fratelli Boselli, or Boselli brothers) in Milan in 1929. The aim was to manufacture their own light commercial delivery vehicles, powered by various small capacity two stroke and four stroke engines. Giuseppe was a talented rider and earned a Gold Medal in the 1935 International Six Days Trial which was held in Oberstdorf, Germany, riding a motorcycle powered by an FB 4-stroke CM model engine. Around this time, FB began to produce its own light truck in new premises in Bologna.

Like most Italian companies, the war took its toll on FB, and it was not until 1948 that Giuseppe linked up with Ing. Alfonso Drusiani to form a new company called Mondial, but which incorporated the FB initials as recognition of the earlier business. The pair reckoned that racing would be the best way to promote their projected new range of lightweight motorcycles, especially with the announcement that the F.I.M. would be conducting the official World Championship for motorcycles (preceding the cars by one year) in 1949, with classes for 125cc, 250cc, 350cc and 500cc (as well as sidecars).

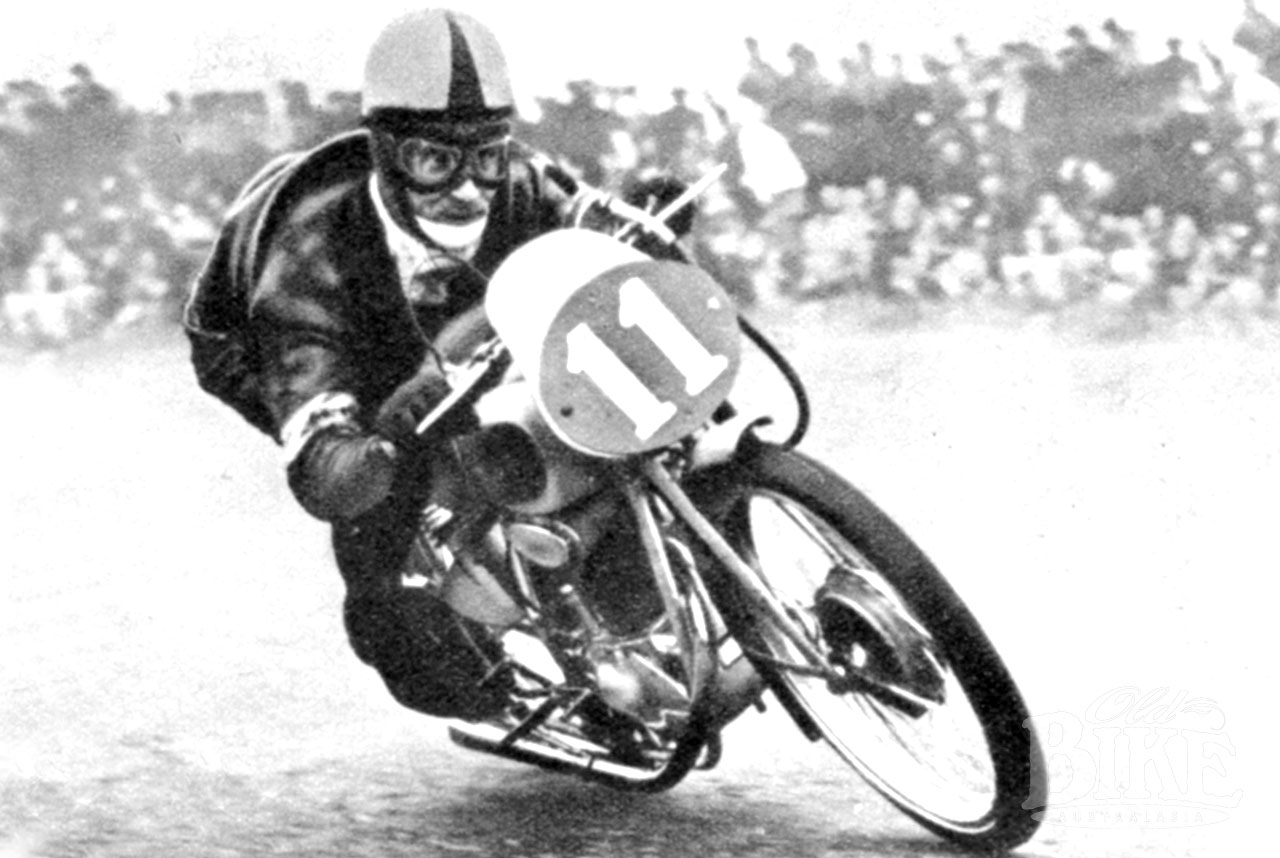

Throwing their hat into the highly competitive world of motorcycle manufacturing in post-war Italy was no small thing, but unlike many of their rivals, FB Mondial chose to go down the four stroke route. The Mondial business was very much a boutique operation compared to MV, Benelli or Moto Guzzi, but Drusiani’s new 125 had the measure of them all. It was a double overhead camshaft single of 123cc which had to run on the mandatory 80-octane petrol of the day, and in the hands of Nello Pagani, it won each of the three races in the 1949 championship to easily land him the title of World Champion. In 1950 Bruno Ruffo and Gianni Leoni took over the works 125 FB Mondials, finishing first and second respectively to again win the championship for FB Mondial, with 20-year-old Carlo Ubialli, who joined the team later in the season, in third place.

The following year it was the same story, but this time with Ubialli as champion. To the amusement of some, especially the British who had no interest in the 125cc class (and very little in the 250cc either), a 125cc TT was instigated at the Isle of Man in 1951. To bolster the squad and provide some local knowledge, Ulsterman Cromie McCandless, whose brother Rex had designed the ‘featherbed’ Norton frame, was drafted into the FB Mondial team, and proceeded to win the two-lap race, averaging nearly 75 mph. The Mondials destroyed the opposition and finished in the first four places. By 1952 however, MV Agusta had tired of being beaten and with their own new four stroke, pushed Mondial back into second place. When Ubialli quit to join MV Agusta, Mondial seemed to lose direction and faded from the scene.

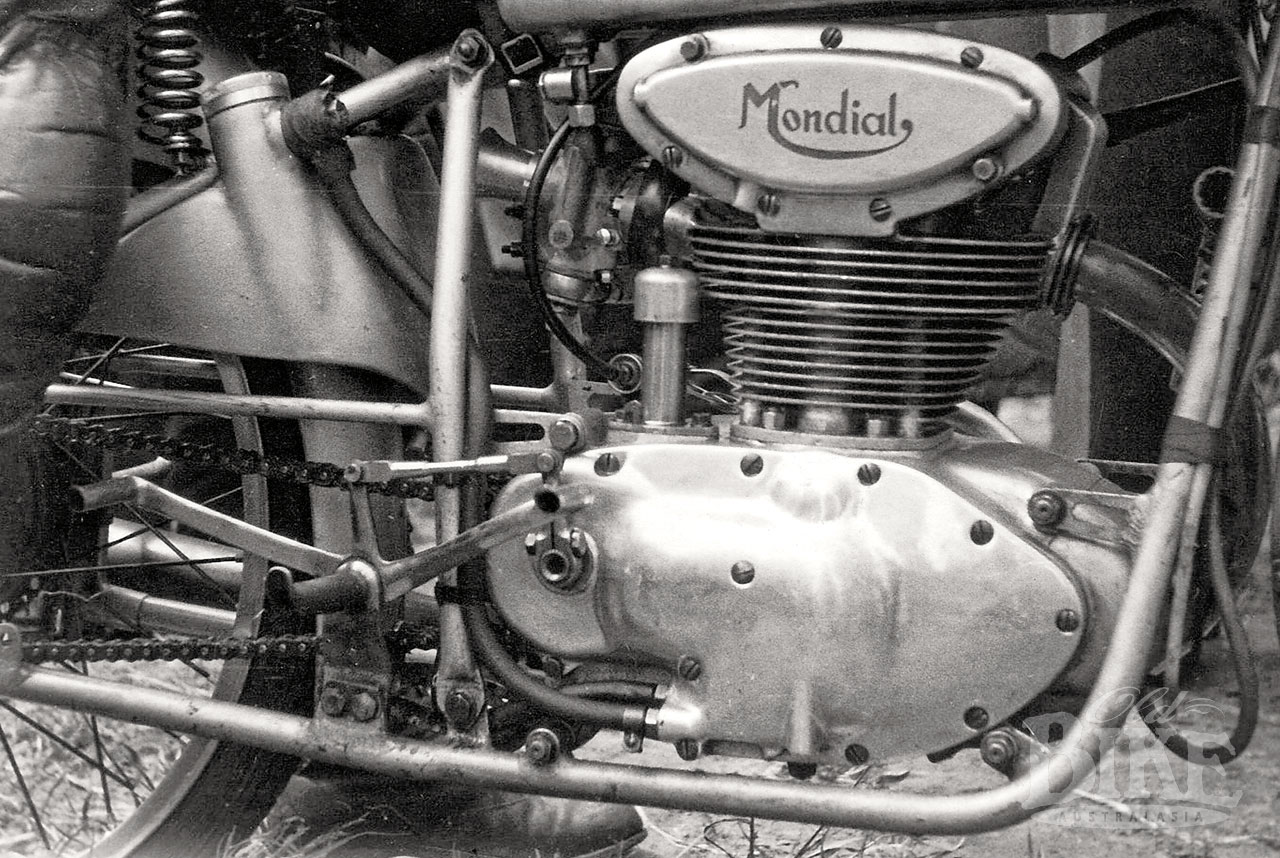

The racer’s engine was developed from the company’s design for its road range in both 125 and 200cc form with pushrod overhead valve operation. These models went on sale in late 1949 and continued with little change for several years. Of all-alloy construction, the little single had the four-speed gearbox built in unit with the engine, with the magneto at the front of the engine.

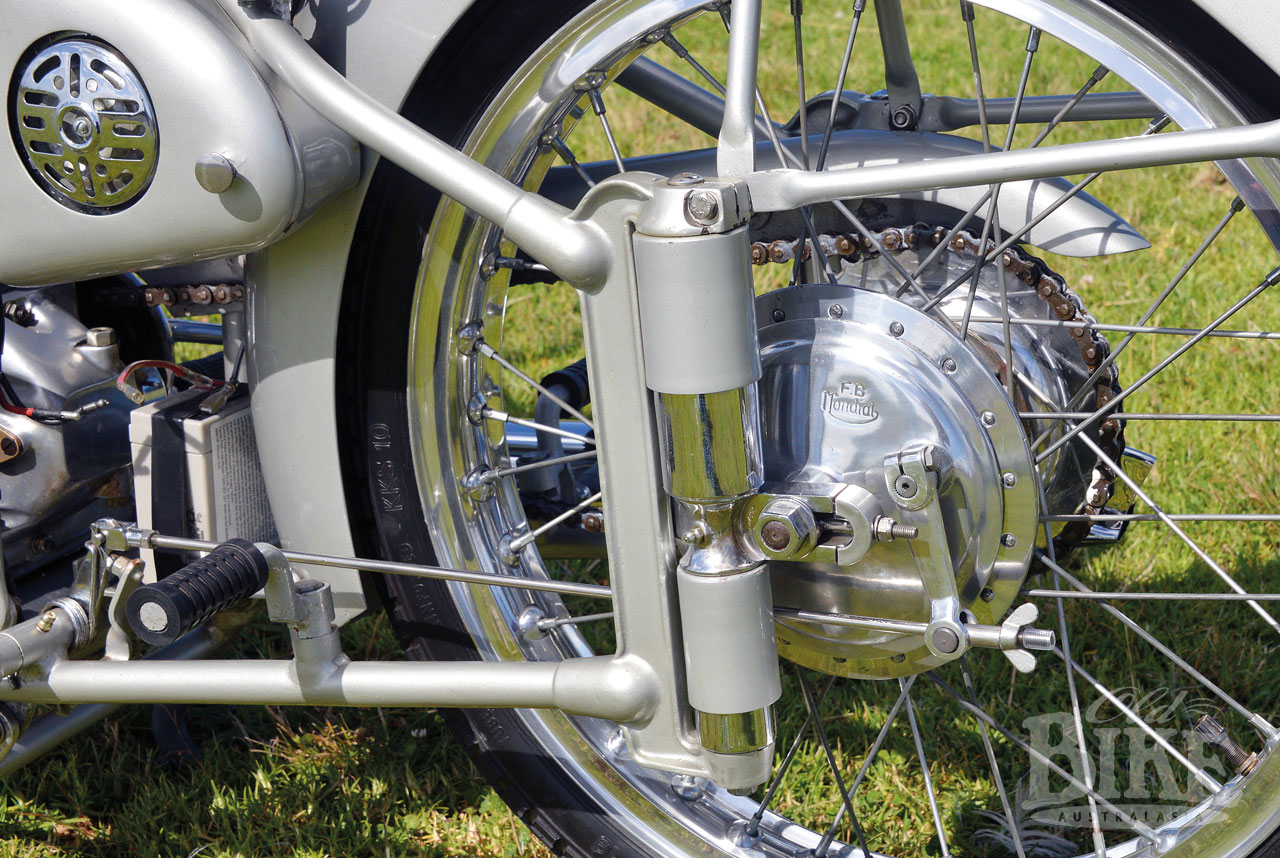

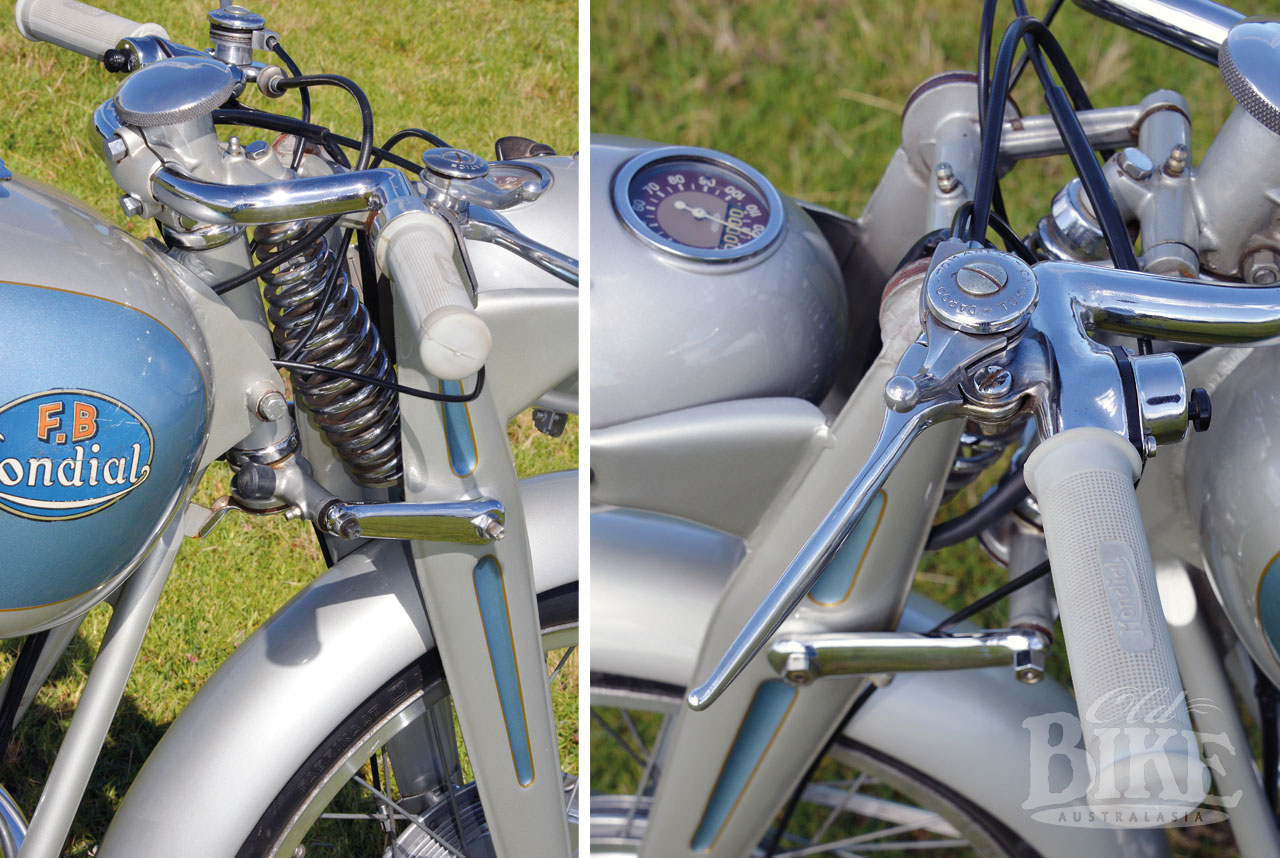

The chassis for both the racer and the road bikes was very similar, and fairly antiquated for the time, with plunger suspension at the rear and pressed-blade girder forks at the front. By this stage, telescopic front forks were almost universal in racing, while swinging arm rear suspension was also rapidly developing in sophistication. Rather than developing a better chassis, Mondial concentrated on reducing weight and extracting more power from their DOHC design.

After 1952, the road bike range continued basically unchanged, but the racers were mothballed while Drusiani developed a brand new design, with some assistance from the young engineer Fabio Taglioni, who was ‘poached’ in 1954 by Ducati. This was produced in both 125cc (the 125 revving to an incredible 13,000 rpm) and 250cc form, with the great Tarquino Provini winning the 1957 125cc championship, and Briton Cecil Sandford the 250 in the same year, but that really is a different story.

The subject of our photos here is a 1950 200cc model, which Melbourne enthusiast Richie Hawkes imported from Belgium in 2012. This motorcycle is wonderfully original and after a little fettling and minor restoration by Richie, it is a real head-turner. Resplendent in FB Mondial’s traditional colours of silver and blue, the little machine bristles with innovative features and beautiful attention to detail.

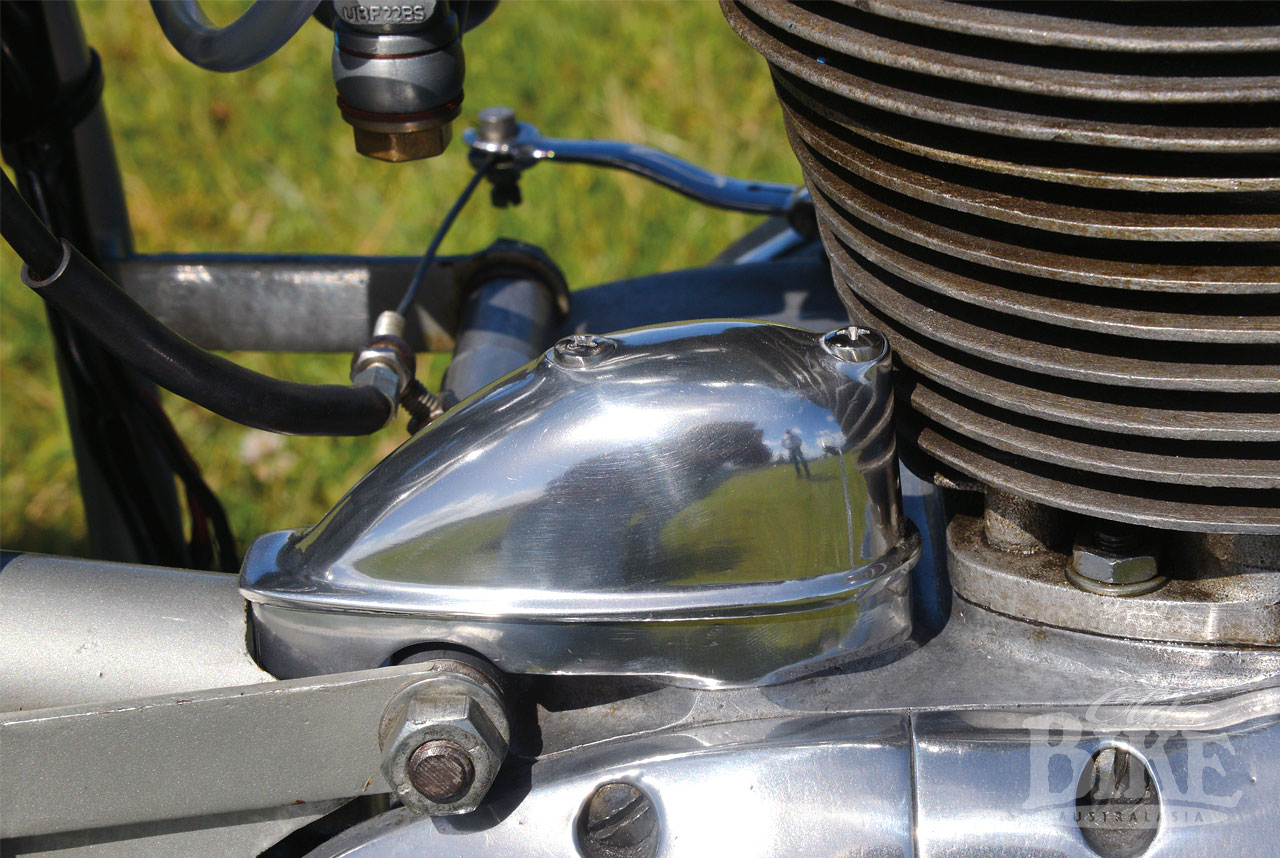

The wonderfully compact engine/gearbox unit has a section at the rear of the crankcases to house the gear selectors, which are externally adjustable. Just above the final drive sprocket is a small tower housing an engine breather, where oil mist collects and is allowed to drip to lubricate the rear chain. A Dell’Orto carburettor supplies the mixture. The kick starter is located at the front of the engine on the right side, and most unusually, operated in a forward direction – a technique that takes some mastering. However the little engine starts easily with the prod, or rather push of the kickstarter, and idles away with virtually no mechanical noise. Just forward of the kickstarter, under another cover is the electrical department which is a combination magneto for ignition and generator to charge the battery. Rather uniquely, the horn sits inside the left side tool box, with another large capacity tool box on the opposite side.

The frame is a wide cradle tubular steel type, with a cast section forming the plunger-type rear suspension. The front suspension looks decidedly pre-war, with pressed blades for the girder forks and a central spring with no dampening. Both wheels are 19-inch with 2.25 and 2.50 tyres front/rear, and have aluminium alloy rims, with cast alloy conical hubs and alloy brake plates; each of which bears the FB Mondial inscription. In typical Italian lightweight fashion, the rider sits on a sprung saddle, with a separate pad for a pillion passenger. The headlight shell houses a Jaeger speedo which reads up to 120 km/h.

Today, the little Mondial racers from the ‘fifties are expensive and highly-prized items – the title winners from the late ‘forties even more so. But the roadsters also attract premium prices as magnificent examples of Italian engineering and design flair. The beautiful castings, the many intricate features that exist more for form than function, and the very Latin lines, make these quite unique bikes. Perhaps the company may have prospered if this flair and obvious passion – and the associated escalation of costs – had been tempered in the way that was adopted by most of its competitors in Italy with the use of universal components and cost-saving engineering – but then it definitely wouldn’t be an FB Mondial!