His eclectic lifestyle totally dependent on the sale of tyres, adman Harry James realised the 1912 Dunlop Dispatch Relay was certain to inflate his pay packet.

Story: Peter Whitaker • Photographs and research: Phillip Smith

No one had done more to foster Australian motorsport than Harry James and if flogging a few more Dunlop tyres was a by-product of his efforts then so much the better. Bicycle tyres were the company’s bread and butter but in 1903 Harry could see the future and sent luncheon invitations to every motor vehicle owner in Victoria – all 30 car owners and 60 motorcyclists. A few weeks later that same group met at the Port Phillip Club Hotel and formed the Automobile Club of Victoria appointing Harry as honorary secretary; a position from which he stood down the following year in the belief anyone connected with the motor trade should be excluded from the Club’s executive.

That didn’t preclude Harry from the Sports Committee or organising a constant train of regularity trials, hill climbs, speed and fuel consumption tests for both cars and motorcycles. It was Harry who conceived Australia’s first long distance reliability trial and, being a proud Victorian, was adamant the event should finish in Melbourne. Thus 23 autos were shipped to Sydney for the start of what became an outright cross-country rally with points lost for a range of various indiscretions; the entire venture to be sponsored by the Dunlop Tyre Company for whom Harry just happened to be the advertising manager. Ten motorcycles and twenty eight ‘motors’ contested the 1905 event which, after a playoff, saw Harley Tarrant driving an Argyll come out on top in one of the longest reliability trials to be staged anywhere in the world.

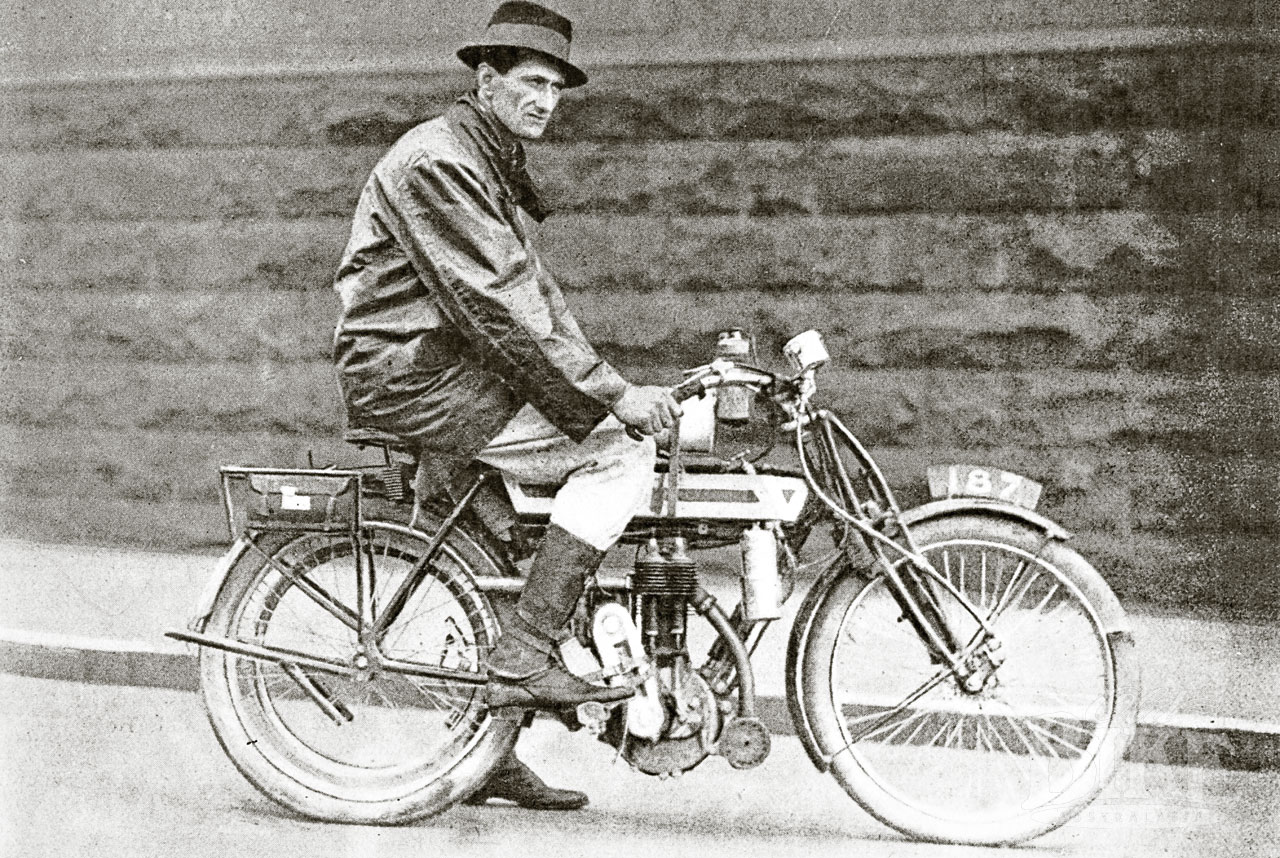

A second trial held later the same year proved even more popular, with front page news reports avidly devoured by the public; as were the accounts of the regular intercity record attempts that followed. However motor cars remained the playthings of the upper classes, perceived by the hoi polloi with equal doses of envy and menace. Even humble motorcycles, with twice the registrations of cars, failed to earn much respect for their riders. Universally shanks pony remained the principal method of travel with pedal power replacing horsepower in the larger towns and cities. And whilst Harry James’ heart belonged to the new 16hp Clement-Talbot in which he and co-driver Charles Kellow set the Melbourne to Sydney record of 25 hours and 40 minutes in January 2008, Harry knew he needed a stimulant for the thousands of bicycle riders that kept him in his job. Hence the 1909 Dunlop Despatch Relay was born.

Le Tour d’Adelaide it was not, yet the concept was simple. Relays of cyclists, their mounts suitably shod with the latest Dunlops, travelling in pairs, would carry a sealed Military Despatch Pouch from Adelaide to Sydney via Melbourne. It was a promotion with which the public could readily identify as velodrome racing was then perceived as more glamorous than cricket, regularly drawing crowds of 20,000 or more. The cyclists managed the feat in sixty three and a half hours which, as no motorcar or motorcycle had made a counterclaim, became ‘the record’. At the time the notorious stretch of deserted coast swamp named the ‘Coorong’ inhibited any intercity records between Adelaide and Melbourne until Murray Aunger took a crack at it in 1914. Meantime, after Harry James’ success in 1908, the Melbourne to Sydney record had been lowered to less than 20 hours. But for then the Adelaide-Sydney record belonged to the pedal pushers – though with over sixty of them, the pedestal was a little crowded.

Three years later it appeared obvious that no matter how many fit and fresh cyclists were enjoined, the days of a cycle relay being competitive with motorcycles or cars had long passed. Motorcyclists and ‘carists’ vehemently argued they could achieve any long distance challenge in half the time – cyclists were no longer in the race. Still dependent on the sale of cycle tyres but realising their future would be determined by petrol power, Dunlop faced a marketing dilemma. For Harry the dilemma was far more personal; his next week’s pay packet.

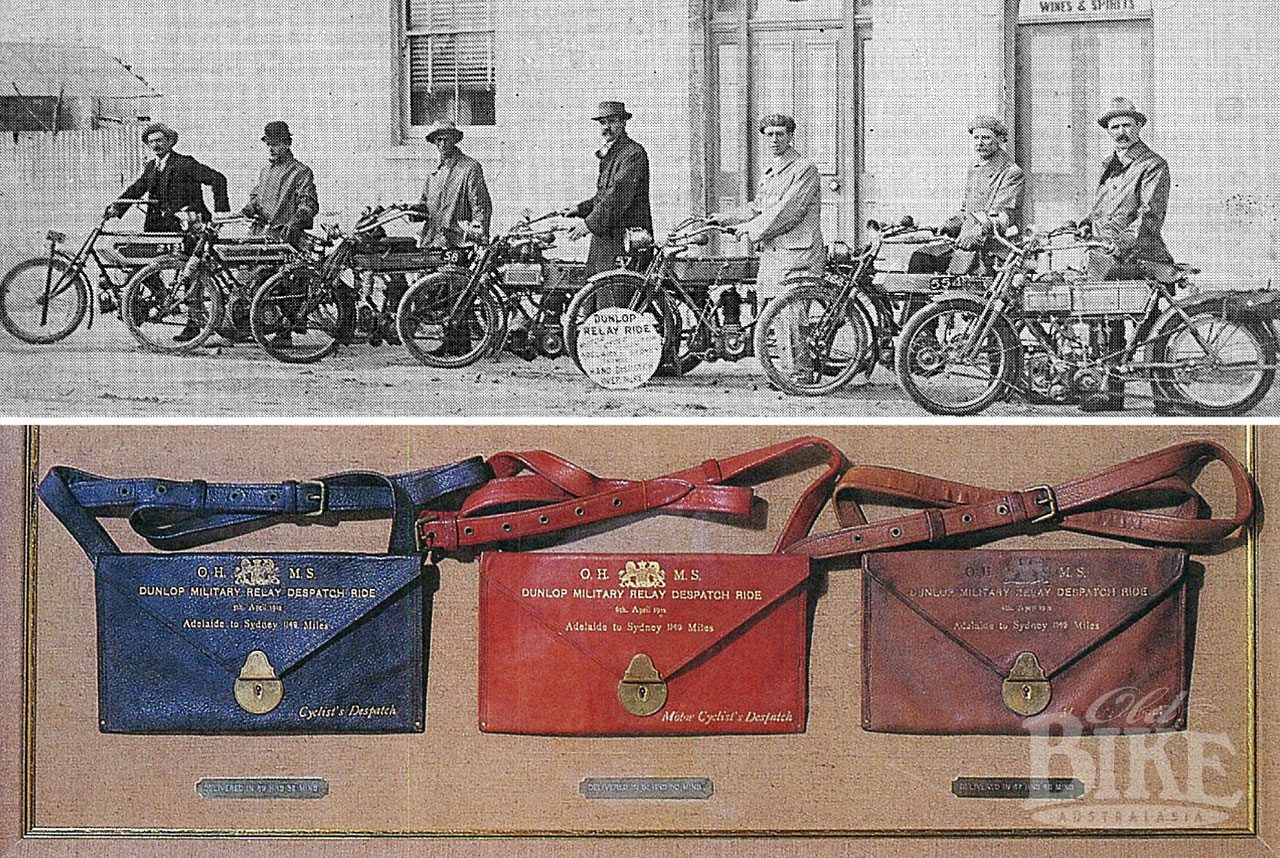

Considering his earlier promotional success Harry had little problem convincing the Dunlop board to sponsor a second Military Despatch Relay; this with teams of cyclists, motorcyclists and cars competing against one another. The popular pub topic of the relative speeds and reliability of cars and motorcycles convinced Harry the event would stir up even more interest. The course would replicate the 1909 event, covering 1149 miles between Adelaide and Sydney and Harry realised that to maximise publicity the three divisions needed to be handicapped in such a manner to ensure a close finish. Surely an impossible task.

However, in what must remain a unique achievement, Harry had already set three world records; the first for cycling 25 miles in one hour, the second for riding a motorcycle 460.5 miles in 24 hours and the third for driving a 1903 Darracq a total of 777 miles in 24 hours. Who better to take a stab at handicapping such an unknown as the 2012 Dunlop Despatch Relay? Yet when the handicapping was announced it caused a furore in the cycling world.

Harry’s plan was for the cyclists to leave Adelaide at five am on the Good Friday, the motorcyclists to set out 24 hours later and the cars a further six hours behind, hoping all three divisions would arrive in Sydney to be greeted by enthusiastic readymade crowds on the holiday Easter Monday; but the cyclists disagreed with this premise in their thousands. Though only sixty odd would take place in the event, hundreds more would participate as timekeepers at more than sixty relay points along the route. Sensing controversy the press entered the fray fully knowing where the sentiments of their readers lay. The cyclists were shabbily handicapped, the front pages decried, and would be overtaken by the motorised divisions before the relay reached New South Wales. One of Dunlop’s board members, Richard Garland, fronted Harry to remind him the company’s bottom line was dependent on bicycle tyres not car tyres. It made no sense to treat such loyal customers ‘shabbily’ but Harry held his ground arguing that despite the greater speed of the motor divisions the cyclists were more reliable and had every chance of a win based on their performance and experience in the 1909 event.

The 1912 route was no easier than it had been three years earlier. What roads did exist were formed mud embankments often washed out by rain which flooded the many fords en route and there were considerable tracts of unoccupied country with a good deal of hill climbing. Despite there being no reward other than being selected and receiving a coveted medal of participation, Dunlop had no trouble in attracting 130 cyclists, 52 motorcyclists and an even dozen car drivers to tackle the event. There were 63 relay sections for the cyclists and only 4 for the cars with 23 for the motorcyclists; the shortest being the twenty one miles across the dreaded ‘Coorong’ from Claypan Gate to Kingston and the longest from Wickliffe to Ballarat at seventy three miles. If the shorter section sounds like a doddle it needs to be understood that the conditions were such in the Coorong that the motorcyclists were only 60 seconds faster than the cyclists who had the advantage of picking up their transport and hoofing it through the swamps and across the sand dunes.

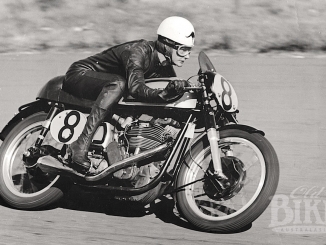

So, at 0500 hours on Good Friday 5 April 1912, all this was still before the competitors as Colonel Hampson passed over the first of the three Despatch Satchels to the lucky rider who pedalled off into the driving rain and stiff headwind; conditions which caused Harry James to doubt his handicapping system. But as he had anticipated each division suffered their own particular misfortunes, not least the motorcyclists. Riders became lost when their rudimentary carbide gas lamps failed, mud clogged up between the guards and frames, bearings failed and carburettors became waterlogged. Flat tyres and broken spokes were common though not as common as heavy falls with resulting injuries. Most of the machines, Triumph, Peugeot, Abington, JAP, Norton and Lewis included, generated no more than 3.5hp in ideal conditions, but with carburettors clogged with a mix of mud, sand and water they could have been fortunate to put out half that power, yet it was power enough to seriously injure three riders and disable scores more.

Excerpts from the post-event reports supplied to Dunlop reveal a monotonous and endless uniformity. “Had a trying experience; black soil track practically unrideable owing to rain. Many falls; mud kept clogging both wheels, so that it was impossible to move them until scaped out. Continued across Coorong after finishing my relay, delayed owing heavy rain, spent miserable night in bush without a drink or food for 26 hours…Had two falls when travelling over 35 miles an hour, buckling back rim beyond repair, and other damages. Rode the 72 miles in 2 hours 1 minute. Team mate travelling fast across culvert on a turn had too much pace up to get around in wet. Put his foot out to save fall and struck culvert post, fracturing leg just above ankle; taken to mount Gambier Hospital by train, where he lay nearly a week before leg could be set, owing to bad bruising and swelling… Tracks almost impassable, many falls in dark, had to push machine quarter mile through plowed up track, did my very best under the wretched weather conditions … Roads wet and very much cut up; dark squally… road slippery, team mate crashed into a stone wall, smashing front wheel and bruising shoulder; came on alone; several skids, trouble with lamp… Bitterly cold in early morning, strong headwind, could not see road for miles owing to phenomenal dust storm, narrowly escaped several collisions… Had five falls; my mate never turned up. The reason – rode off course, when returning buckled rear wheel, causing cover to blow off. Riding back to starting point in dark, front wheel went down between planks over culvert; result – broken front axle, bent forks and a severe shaking. Had to push machine several miles… thirty one miles in 64 minutes (the worst road on the whole route)… Had bad fall, shot off track going through a narrow opening between two trees; twenty miles further on frame of machine broke in two, throwing me heavily; smashed hand, breaking bone. Ran back to Wodonga, obtained services of pony and sulky, galloped into Albury, and delivered dispatch… Only hit two fences, one coming down Jugiong mountains; lamp smashed, lost tools, had to go back for them… first mistake, took wrong track and stopped in creek; second, ran into fence, freezing cold, soaking wet, back cover blew off; tube caught in back sprocket, breaking guard and belt; unable to continue; had to push machine (200 lbs) 25 miles. Dark… Walked razorback, surface impossible to ride; picked up machines at top; rough coming down. Good run into Sydney.”

An endless litany of sodden misfortune apart from the one bloke who got caught in a dust storm and the bloke who rode the final leg into Sydney. The cyclists can’t have had it much easier but with far shorter relay sections, the ability to jump off and walk, or at least crash at lower speeds, the pedallers displayed a fine spirit of perseverance and, far from being caught before Albury as was predicted, the leading cyclists passed through Goulburn whilst the motorcyclists were approaching Gundagai and the cars had just reached Albury. With the dreaded Razorback ahead of them all it would appear to be a close run race.

However all the hoohah raised by the cyclists pre-event was just that. Harry James had been vindicated and had, in fact, overestimated the speed of the motorised divisions as opposed to underestimating the collective efforts of the bicycle brigade; the final riders of the 130 strong relay team rolling up to the Sydney GPO at 3am on Easter Monday. The motorcyclists were next to deliver their Despatch at 9:30am with the first car – the Chalmers of Messrs. Sandford and Campbell following at 10:14 am without the Despatch. Their team-mates Messrs. Gale and Heron who had charge of the Despatch Satchel for the Albury to Sydney leg had become geographically challenged somewhere south of Goulburn, lost over an hour and thrown away any possible chance of victory.

The statistics aside everyone was happy, the automobilists, or ‘carists’ as they were then known, proved their speed superiority at an average of 24mph, the motorcyclists averaged 22mph but the Commonwealth Department of Defence announced that motorcycles would figure in future defence schemes as they were less likely to be ‘rendered useless’ than motor cars. Of course the cyclists were ecstatic that they were the first over the line in Martin Place. Even the popular press were happy as the event drew attention to the deplorable conditions of Australia’s country roads. And certainly a bone was thrown by the military to the vast number of stewards, scrutineers and timekeepers who gave their time to participate in the massive exercise that generated over 1500 telegraphic messages over three days.

Even more happy was the board of the Dunlop Tyre Company who, for the alleged cost of 300 quid to organise and manage the event, reaped rewards far greater than those hardy souls they organised. All for no more than the following recognition from the organisers “To the Sportsmen who volunteered their services and took part is this Event we tender our sincerest thanks. The ride was a big undertaking – made possible only by the splendid cooperation of men who, for no gain, tendered their services and carried through their appointed duties irrespective of personal discomfort, personal risks, loss of time, hard work and, in many cases, considerable expense. It has been a pleasure on our part to come into contact with men who ‘for the love of the game’ volunteered their services and ‘made good’. The event was a great success and we keenly appreciate the efforts that carries through the demonstration to such a successful issue.”

Happiest of all was Harry James who continued flogging tyres and organising events such as the International Alpine Rally until his retirement from Dunlop in 1951.

On His Majesty’s Service

Though magnificently packaged, each of the three communiqués consisted of no more than a greeting from Colonel H. Le Mesurier, Commandant of the Colonial Military Forces in South Australia to his counterpart in New South Wales. The purpose of the message was stated thus:

The three methods adopted for conveying the message will, it is hoped, create in the minds not only of those taking part in the transmission of it, but also in the minds of the community, the great possibilities of the Cycle, Motor Cycle, and Motor Car in operating for the defence of our country, the burden of which should be regarded as the privilege of each to bear his share, and further to stimulate them individually as well as the manhood of Australia in that direction. Needless to say. I am writing with the deepest interest the progress of the three messages, and I wish all concerned in tis conveyance every success.

All up not a bad PR coup for Harry James on behalf of the Dunlop Rubber Company.