Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Stan Shephard, Gary Reid, Ray Smith

9th December, 1957 was a grim day for motor sport in NSW. An amendment to the Metropolitan Traffic Act, 1900, and the Motor Traffic Act, 1909, officially termed Act No, 69, 1957, passed through the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of NSW. It became officially referred to thereafter as the “Speedway Racing (Public Safety) Act, 1957”, and after much debate and discussion, was finally implemented on April 2nd, 1959.

Amongst the definitions in Clause 2, “ ‘Meeting for Speedway Racing’ means meetings at which racing between motor vehicles is held or carried on and includes meetings at which events, not actually races, in which vehicles compete singly or otherwise, but which speed is the determining factor, are held or conducted”. It added, “ ‘Speedway’ means any ground, land, park, racecourse, oval, recreation reserve, sports ground, or place whether enclosed or unenclosed on which meetings are held, and includes any land or building used in connection therewith, but does not include a public street within the meaning of the Motor Traffic Act, 1909, as amended by subsequent Acts.”

It went on to stipulate under which conditions licenses for the promotion of motor racing on such venues would be issued, but the short answer was that not a single circuit in Australia’s most populous state complied.

The effect on the sport was akin to pouring Roundup on a weed. Only the delay in implementation – 16 months, allowed the wiser heads to contemplate what course of action could be taken. The majority of circuits simply closed down, including the only permanent road racing track at Mount Druitt and dozens of dirt Short Circuits scattered around the state. The only scrambles track, at Moorebank, was rebuilt in order to comply, but twice failed the stringent inspections, causing the cancellation of several meetings in early 1959.

Ironically, the venue that had caused much of the police scrutiny, the Sydney Showground Speedway, required comparatively minor work to fences and was granted Speedway Licence number one.

In the Newcastle area, known in motorcycling terms as the Auto Cycle Union (ACU) Northern Centre, Short Circuit tracks were everywhere, ranging from little more than paddocks to well established circuits like Hillview at Muswellbrook.

At Edgeworth, the Mayfield Club had managed to arrange for the use of a plot of swampy land owned by the Catholic Church, adjacent to Cockle Creek, as far back as 1953, where the thick bush had been used as a Hunt Club in the 1930s. Most weekends would see working bees where Mayfield club members worked on clearing the land with a view to building their own Short Circuit, which they named “The Pines”. A tributary of Cockle Creek, known as Salty Creek, ran through the area, and the track was generally referred to thus. It was no overnight achievement, as Bruce Turnbull recalls. “We had an arrangement with the (Catholic) church to pay them a dividend from the gate takings at race meetings – the club never actually owned the land. Six of our club members guaranteed the success in signing the leasing to the Catholic Church. They stood to lose very severely if it failed and were advised by John Stevenson’s father, a JP, not to sign. Then we had to raise the money to build the circuit and put the fences in.”

Bruce’s brother Ivan has similar recollections. “Salty Creek was just one of the properties where we (Mayfield MCC) used to have club runs, the added attraction was a swim in the creek after a hot day. The track area was defined by a row of pine trees on each side, hence the name, ‘The Pines’. The fences were made using old railway sleepers and planks removed from old railway coal wagons. Using cross cut saws, we cut them to length and were they hard, heavy and splintery, and we had to drill them with the brace and bit or an auger to be bolted to the railway sleeper posts. Many members put in countless hours to bring it to fruition, some using their holidays to get completion for opening day. President of that time, John Stevenson procured a lot of 44 gallon drums of waste oil and using his firm’s Morris van, it was moved to the site. A large spreading pipe was screwed into the drum whilst vertical and in a trailer, tipping it over was a risky business, to begin the trickles all over the track.

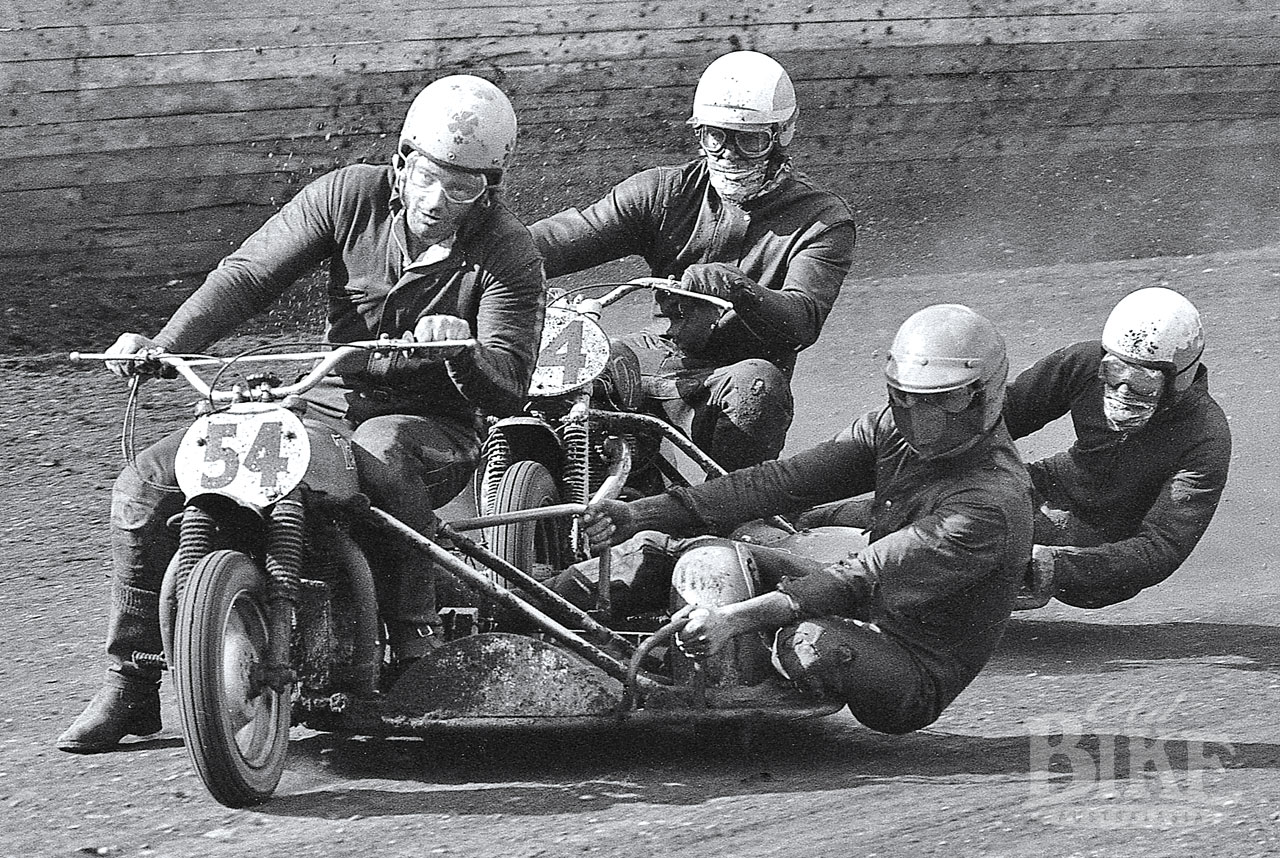

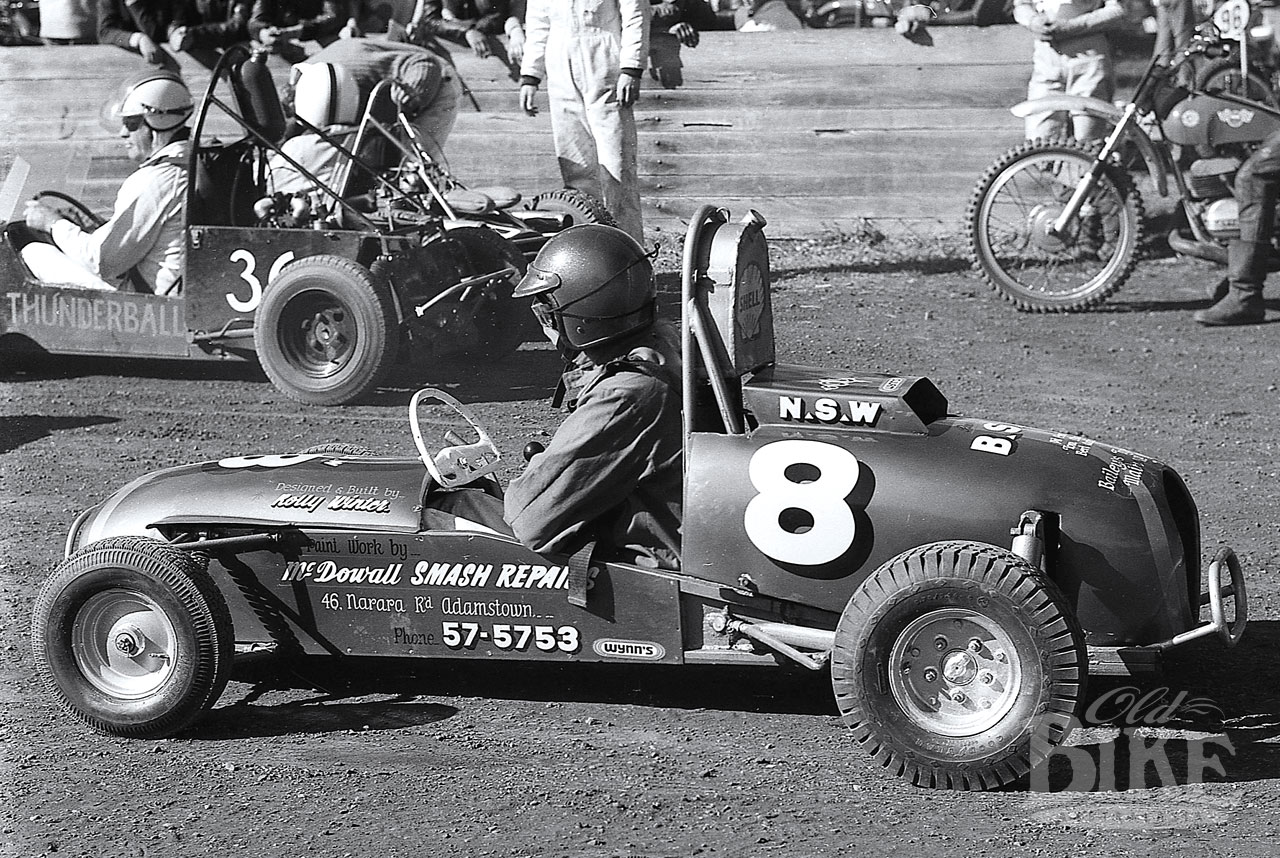

By early 1958, the track was beginning to take shape, and with the spectre of the Speedway Act ever present, the track was constructed to the required specifications from the outset. The land sloped gently towards Cockle Creek, the main straight running uphill to a fast speedway-style corner. The return run incorporated a right hand bend (known as Frog Hollow) with a sharp left hand corner leading to a faster exit back onto the main straight. The one-third mile (530 metre) track was 33 feet wide throughout, making it suitable for sidecars and the booming TQ (Three Quarter) 500cc midget cars that were very popular in the area. A wooden safety fence encircled the track, which was reached via Penrose Street, one kilometre from Edgeworth Station and 20 kilometres from Newcastle itself.

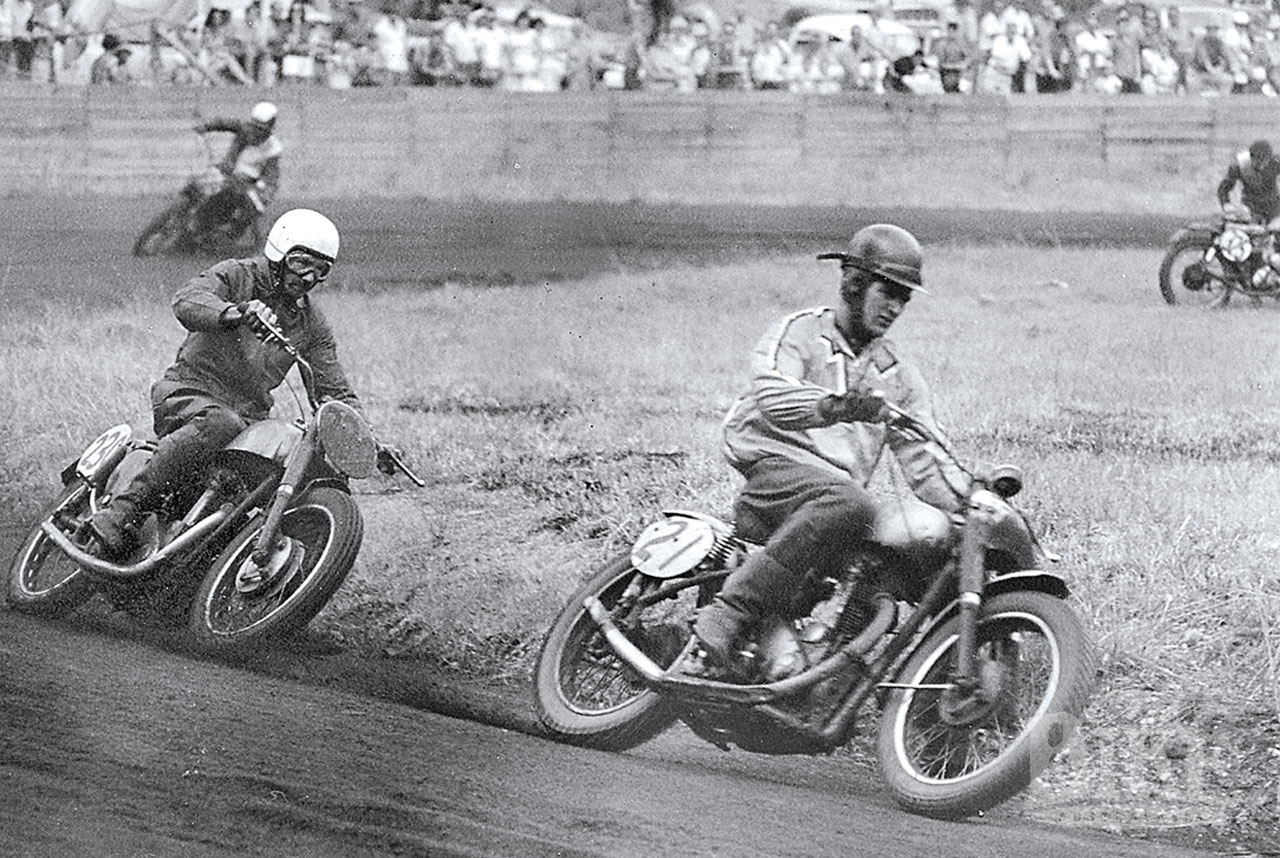

Salty Creek received NSW Speedway Licence Number Two, and the opening meeting was set down for March 9th, 1958. Liberally saturated with old sump oil, the surface was dust-free for a 52-event programme that was watched by a healthy crowd. Stars of the day were Cessnock’s top rider John Rumford who won the Lightweight and the Senior A Grade, Harold Campbell from Bankstown and Ariel-mounted Sydney sidecar man Tommy Carr from Merrylands Club. Ivan Turnbull, was the winner of the Ultra Lightweight event. Two months alter it was on again, but this time the local stars were trounced by the visiting Sydney duo, Les Fisher and Roy East, while Joe Riley, also from Sydney, took out the main sidecar event. 50 events were run in rapid-fire succession, one race beginning the instant the final rider from the previous race had returned to the pits. Except for when the track was being graded, the longest period between races was 62 seconds!

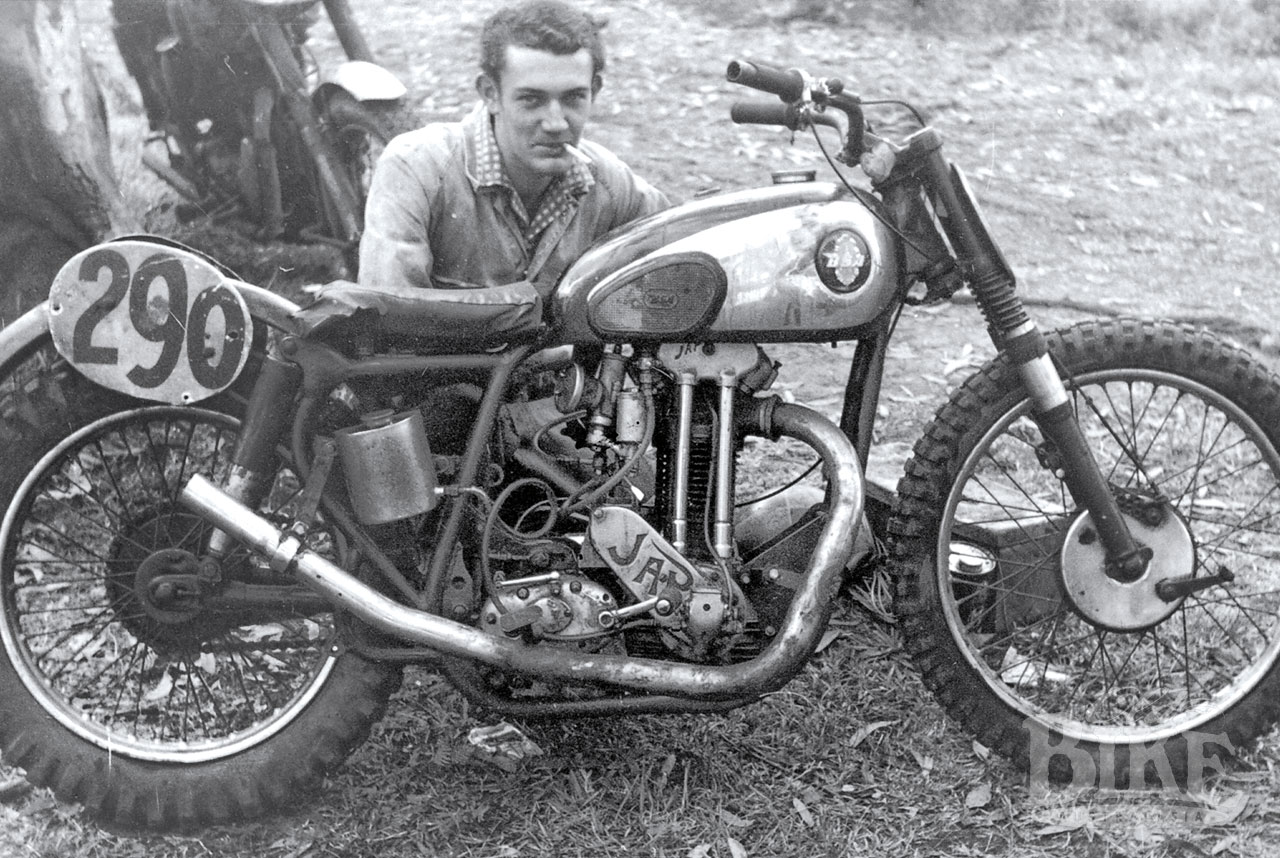

Salty Creek quickly established itself as a favourite with riders and fans alike, with riders like Dave “Sputnik” O’Brien, Pat Fernance, Keith and Jack Davies and Sydney star Jim Airey being regular winners. Despite a perennial lack of manpower to do the maintenance, which always seemed to fall to the dedicated few, Salty Creek went from strength to strength, along with the nearby Heddon Greta circuit. As the ‘sixties dawned, a new wave of stars emerged, most notably William ‘Herb’ Jefferson, who rocketed through the C and B Grade ranks to become the hottest property on the Short Circuit scene, and Kevin Fraser, younger brother of ‘fifties star Norm.

Major events such as national and state titles seemed to bypass Salty Creek, and in the ‘sixties the track’s big race of the year was the City of Newcastle Championships. For the March 1962 running Mayfield club members slaved away to prepare the track in top condition, including grading a foot of material off the entire circuit to eliminate the notorious pot holes, and dousing the surface with 14,000 gallons of used oil. The new surface certainly suited Dave O’Brien, who won the Junior, Senior and Unlimited titles. Just weeks later, all the hard work was literally washed away by a major storm which did extensive damage to the track and caused the cancellation of the next few scheduled meetings. At the November meeting track conditions were so bad that after several major accidents, police stepped in and put a stop to the meeting. Prior to this, Gordon Hellyer was the outstanding competitor, winning the 125 and 250 solo finals as well as all three Sidecar races.

“A club initiative was the 1963 NSW Club Teams Championships,” recalls Ivan Turnbull, “won the first year by Wallsend, one point ahead of Mayfield. On the second occasion those two clubs dead heated and in the run off I won, with Peter Wilson second to secure the title. Wal Martin had loaned me his 500 motor. I usually rode my 350, so it was momentous for me as a B grader at the time when Wallsend had at least 2 A grade riders in their team on JAPs.”

By the mid ‘sixties, Herb Jefferson, Kevin Fraser and Keith Davies were usually at the front of the solo classes, although veteran O’Brien could still not be discounted, while Gordon Hellyer, George Watson, Jim Gilbert, Bruce Bowtell and Wal Hambly were generally the class of the outfit events. The English Hagon frames, plus numerous others including local copies, had revolutionised the Short Circuit scene, and by the close of the decade – just as had happened in motocross – the old heavyweight stock frames were gone.

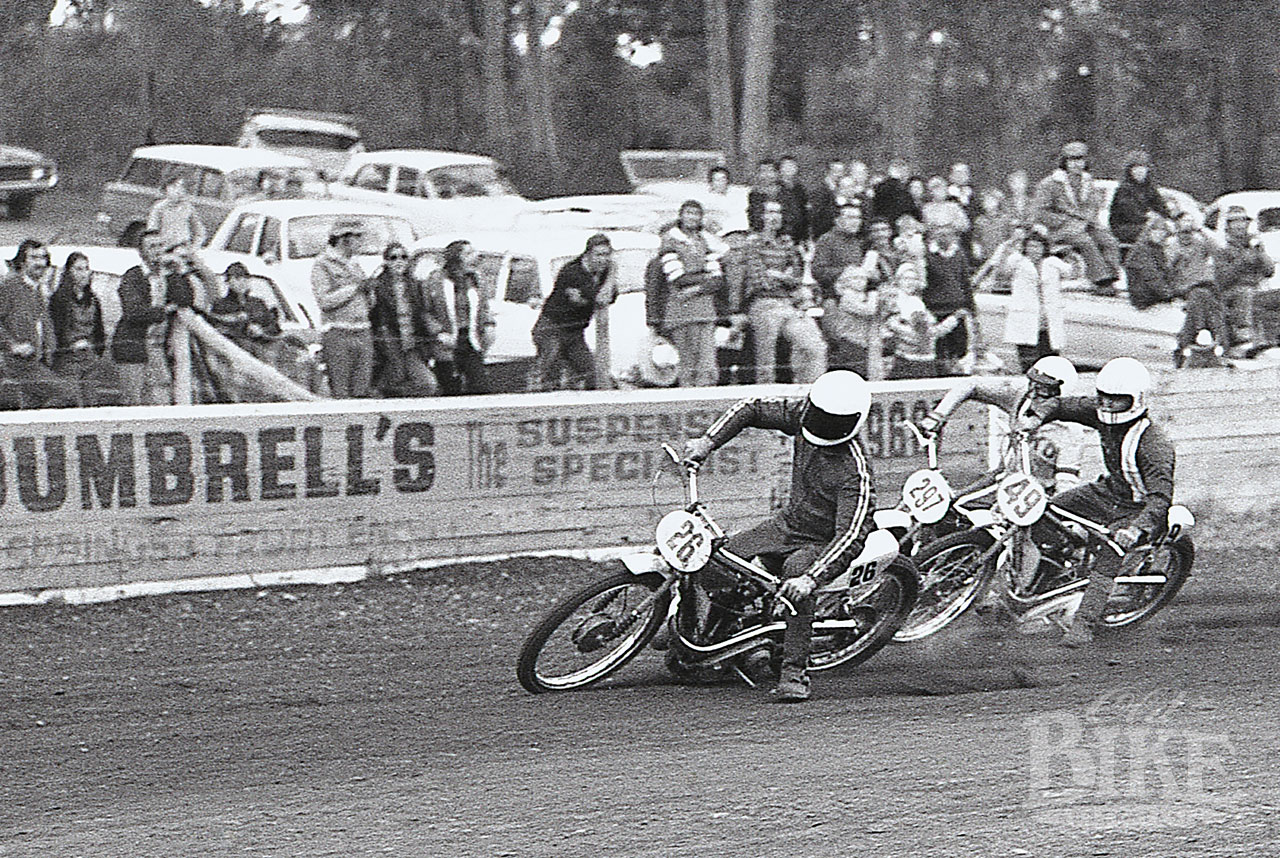

As the ‘seventies dawned, many of the former riders were gone too, notably Jefferson, who had swapped his leathers for a wetsuit and taken up pro surfing, Dave O’Brien, and John Rumford. But Keith Davies, already a veteran of the sport, was going as strong as ever with a stable of well prepared machines, as was Kevin Fraser, and new faces like Greg Primmer, Stuart Mason, Terry Saxon, plus Sydneysiders Bill McDonald and Terry Poole kept the action coming thick and fast at Salty Creek. The sidecars were always a feature of the program, with Joe Cox, Jack Pearce and George Watson among the front runners in highly competitive fields. The bikes suffered an uneasy coexistence with the TQ cars, which were always a part of the program and in 1971, staged the Australian TQ Championships at the track.

1972 was perhaps the biggest single year for Salty Creek, with a string of big meetings, a round of the NSW Championships, and in December, the running of the England versus Australia ‘Test’ match. Earlier in the year, the traditionalists were shaken when speedway star Jim Airey turned up with his speedway Jawa fitted with a rear brake to comply with regulations, and despite a single gear, cleaned up. Other oval track riders like Ricky Day tried the same stunt, but it was a short-lived fad. The state title round in July is remember not so much for the dominance of Kevin Fraser, but the fatal accident to Garry Poole, younger brother of Terry. There was much less activity during 1973, but the following year began with Round 4 of the re-vamped England versus Australia series in February, when the visitors finally got the measure of the home side 56-51. John Langfield won two of the three heats and Kevin Fraser the other, but the locals suffered several machine failures and falls.

By the mid ‘seventies however, the spark seemed to have gone out of the promotions. One factor was the motocross boom, with tracks springing up everywhere throughout the Hunter region and the availability of the latest models straight from the showroom floor. Another was the encroaching development. As far back as 1968, local ambulance man Edgar Lideman saw the need for a Retirement Village in the area and approached businessman Albert Hawkins for a donation. Hawkins donated 40 acres of village land adjacent to the circuit, and formed a partnership with the Royal Freemason’s Benevolent Institution. The first of these buildings was completed in 1972, with a Residential Care Hostel completed in 1975. But it wasn’t just the threat from the developers that led to the demise of the circuit at Salty Creek.

One of the founders of the circuit, Bruce Turnbull said a lot of the blame for the closure of the track in the mid seventies was due to the demands of the TQ drivers. “We (Mayfield club) really only wanted to run about four meetings a year, but the TQ mob flattened us. They wanted more and more meetings – seemed like one a month – and we just ran out of workers.”

“The Hunter Valley was very much the centre of short circuit racing in NSW,” says Ivan Turnbull, “with tracks also at Cessnock, East Greta, Heddon Greta, Muswellbrook, Aberdeen, Tamworth, and on the fringe at Taree. Except for December and January, when it was too hot, one could ride almost every weekend if you could afford it. Great sidecar racing was always certain with Gordon Hellyer, Jim Gilbert, Bruce Bowtell, John Dunscombe, Frank Café, Jack Pearce and crews and with many others. I decided to move to NZ in 1961, so my part in Salty Creek came to an end. A visit to the site about year 2000 was a shock. I had expected to see some evidence of the track or fences, but it had reverted to bush, the oil seeming to have not held back any vegetation, and the pine trees long gone. It was not the greatest site, but we made the best of it and the pleasure derived is immeasurable.”