From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 91 – first published in 2020.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Brian Darby

From the moment Speedway racing hit England in 1928, it was touted as the bastion of rough-riding, swashbuckling he-men, who earned big money and lived large. And while all this was true to a certain extent, the men didn’t have it all their own way. For a brief period in England, and an extended period in the Southern Hemisphere, a small but very competent band of women gave as good as they got.

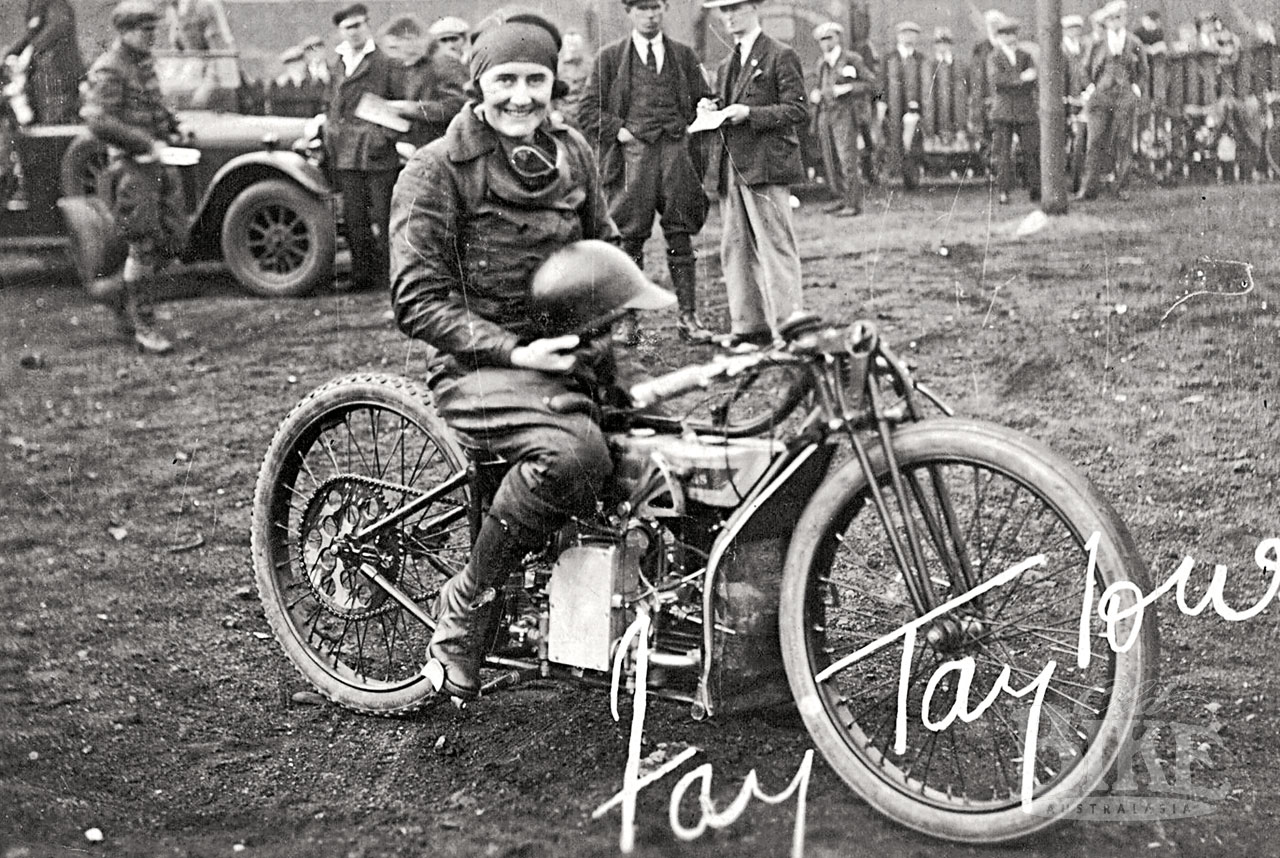

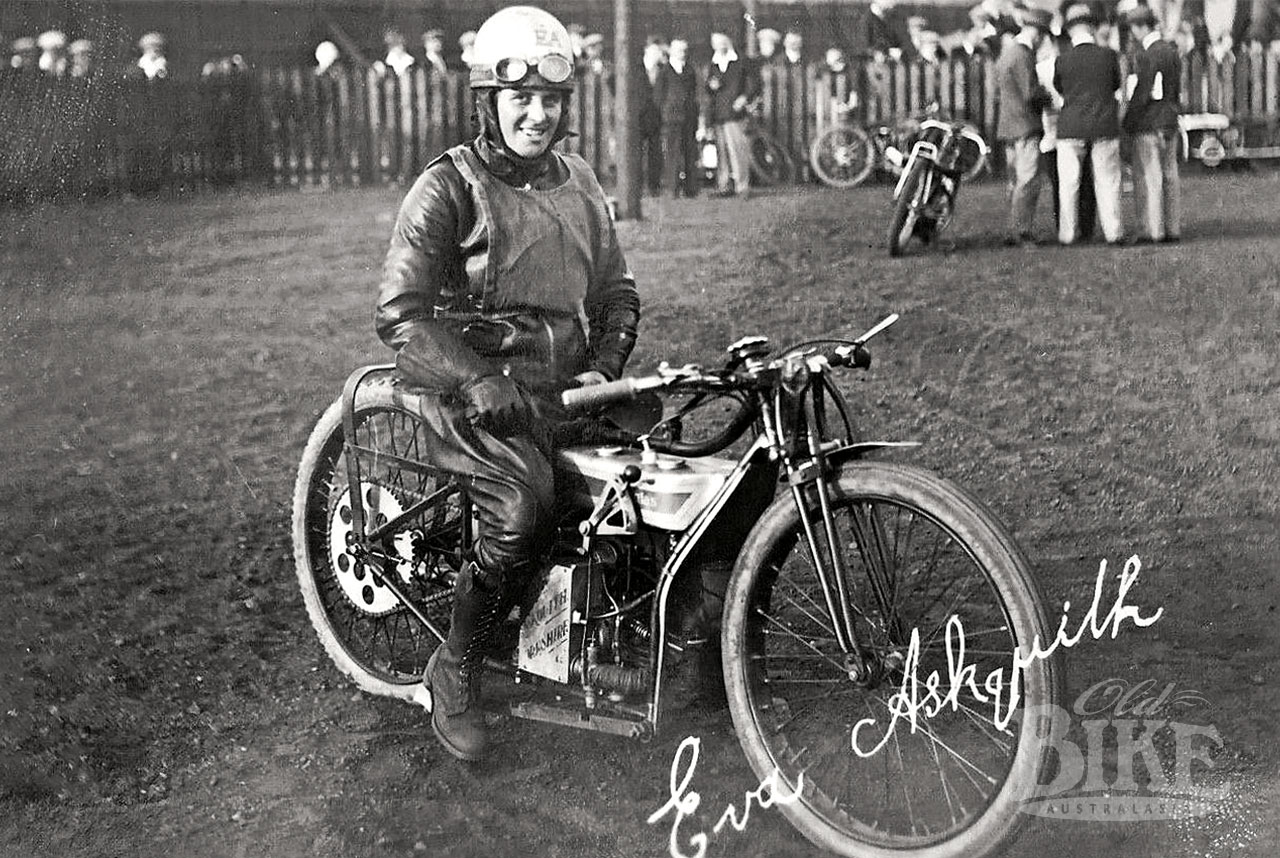

1929 was a good year for the girls, with Babs Nield, Jessie Hole, who initially raced as “Sunny Somerset”, Dot Cowley, Gladys Thornhill, Eva Askquith and Frances “Fay” Taylour featuring on race programs across the country. The latter two, Askquith and Taylour however, were considered far superior to the others, and Askquith generally held to be the top woman rider. It was Taylour though, born in Birr, Ireland in 1904, who seemed to garner the major share of the publicity, as much for her take-no-prisoners demeanour as her results.

Askquith, on the other hand, was reportedly reserved, sensitive, peace-loving, and strictly tee-total. Eva, one year younger than Taylour and a native of North Yorkshire where she worked initially as a butcher’s delivery girl, was a versatile competitor, excelling in grass track, trials, and hill climbs prior to turning to speedway aboard a Dirt Track Douglas. As well as competing at tracks all over Britain, Eva took her Douglas to Copenhagen, Denmark in May 1929, where she was very successful to the delight of the local promoters. Back in Britain, Eva left her northern base to come to London for a series of match races against Fay Taylour at Wembley. Any thoughts of friendly rivalry vanished when Taylour refused to share the dressing room that had been allocated to them; friendly rivalry became deadly rivalry henceforth!

These match races between the two top lady riders became a regular fixture at tracks across the country, but there were no other challengers. As Eva said in an interview with speedway historian Cyril May, “ Some of these girls really ought to have been banned from dirt-track racing altogether, as they simply had no idea. I don’t think they had any competitive motorcycling as a background and of how to ride a bike on the cinders. It nearly made me cry. They just fell off with fright.”

Later in 1929, Eva was off abroad again with her Douglas, this time to Spain, to compete at the one-third mile circuit in the magnificent Barcelona Exhibition stadium. After some strong showings, she soundly defeated all comers (including several regular male riders from the British league as well as the local stars, to win the Carrera Scratch Handicap. After just four months at home, she sailed for South Africa where, in addition to competing at the Ellis Park speedway on Johannesburg, she rode in a road race at Natal. She was back in England by April 1930, ready for a full season of local racing.

During this same period, Fay Taylour was doing her share of winning as well. Like Askquith, Taylour was a skilled mechanic, doing her own preparation and maintenance, and like her rival, was never afraid of a challenge. And so, in January 1929, Taylour arrived in Australia, with her Douglas in the hold of the liner. In her first appearance, in Perth, she defeated the local star Sig Schlam, before moving on to Melbourne. Appearances at Goulburn and Brisbane followed. A short tour of New Zealand followed, racing at Wellington, where she injured a hand in a fall, then to Western Springs in Auckland, travelling in a smart white Chevrolet provided by a General Motors dealer. It was then back to Melbourne for a few more meetings, where she defeated star rider Reg West in a match race, before the return trip to Britain in time for the 1929 season.

The Down Under experience had impressed Fay, and she made the trip again at the end of 1929 bringing her Rudge with her. Once again her tour began in Perth, where she was matched against the experienced champion Charlie Datson, who took the victory, a result that was repeated the following week. One week later she was in Adelaide to compete at the Speedway Royale. Despite never having seen the circuit before, she trounced the formidable opposition to win her heat, semi-final and the final of the main event with 100 yards to her closest pursuer. She also competed at Wayville in South Australia before heading by train to Melbourne, with Sydney, Brisbane and New Zealand to follow. Once again Wellington was the first stop in the north island, followed by Western Springs in Auckland, where she defeated Bill Herbert in the Special match Race. It was then down to Christchurch to race at Monica Park, where she told the press that she had “fallen in love with New Zealand.” It was not just a pleasure trip, she also pocketed a very healthy amount of prize and appearance money.

Both Fay and Eva were planning a rigorous campaign for the 1930 British season, but a bizarre incident led to a total change of life for both of them. At an early season event at the Wembley circuit in London, Billie Smith clipped the back of another rider not in a race, but during the rider parade before the meeting started. She fell heavily, breaking a collarbone, and medical staff was obliged to remove her upper clothing to attend to the injury. This utterly appalled the puritanical owner of Wembley Stadium, Sir Arthur Elvin, who had constructed the cinder speedway track in conjunction with colourful New Zealand-born promoter Johnnie Hoskins. Elvin immediately announced a ban on all women riders competing at his track, and reported the matter to the Auto Cycle Union, controllers of the sport in Britain. The ACU responded with similar outrage and extended the ban to all speedway tracks in Britain. Fay, Eva and all the other fast ladies were out of a job, and the ban remained in place until 1988. Significantly, the Speedway Control Board of Australia elected to enforce the ban, meaning Fay’s planned tour for late 1930 was off.

Conjecture surrounding the ban raged on for years, with some insiders maintaining that there were other factors apart from the intervention of Elvin and the ACU. Speedway racing was increasingly very serious business, and the novelty of women riders making up the numbers had worn off for promoters. Many male riders objected to racing against the women, who, with the exception of Askquith and Taylour, were considered dangerous company.

Eva Askquith’s response was to make another sojourn to Spain, where she could race legally, and did so with reasonable success in 1932. But on her return to Britain, she finally hung up her helmet and returned to the family home in Bedale, North Yorkshire, and to her job with the butcher. When WW2 started, she joined the National Fire Service as a dispatch rider, and also as a fire engine driver. Then in 1959, while on one of her butcher deliver rounds, she was hit by a car and seriously injured, breaking both legs and spending almost two years in hospital. Eva never married and had no children. She passed away in 1985, one day short of her 80th birthday.

Fay Taylour, on the other hand, refused to allow the ban to alter her lifestyle. She had actually been on her way home from Australia when the decision was made, and immediately made her opposition known, but despite entreaties from Fay and Eva, the authorities were unmoved. As a ‘farewell’, Fay and Eva were permitted one last appearance, at the Southampton track, in July 1930 – a match race over three contests. As it turned out, only two races were necessary as Fay won both easily, as well as establishing a ‘Ladies’ lap record which was actually the fastest time of the meeting. It was the end of the road for motorcycle speedway for her however, and she returned home to Ireland to contemplate her future.

British speedway was at this time becoming a very professional league, with teams racing largely replacing the individual contests. Fay turned to Europe, loading her Douglas and heading to Germany, where she started in several events. It was of course the period of the rapid rise of the Nazis, and Fay Taylour did her reputation at home no good by voicing anti-Semitic sentiments and openly embracing Fascism.

From here on Taylour abandoned motorcycles in favour of car racing, for which there was no ban on women competitors. She competed in India in 1931, driving a Chevrolet in the 470 km race from Calcutta to Ranchi, which she won in record time. This success resulted in the offer of a start in a women’s race at Brooklands driving a Talbot, and again she greeted the chequered flag first. Later in Ireland she drove in the Leinster Trophy, winning again. Just before the war began in earnest, she drove a works-prepared Riley in the South African Grand Prix but failed to finish.

As the war intensified, so did Taylour’s overt support for Hitler, and she became a member of the British Union of Fascists under Oswald Moseley. By mid 1940 the British authorities had had enough and she was branded an ‘undesirable’, arrested and sent to HM Holloway Prison for women in London. Later she was transferred to the prison at Port Erin on the Isle of Man where she remained until 1943 before she was released to neutral Ireland on the condition she abstain from her pro-Nazi activities, which she did not. M15’s top-secret file on Taylour described her as “One of the worst pro-Nazis in Port Erin”.

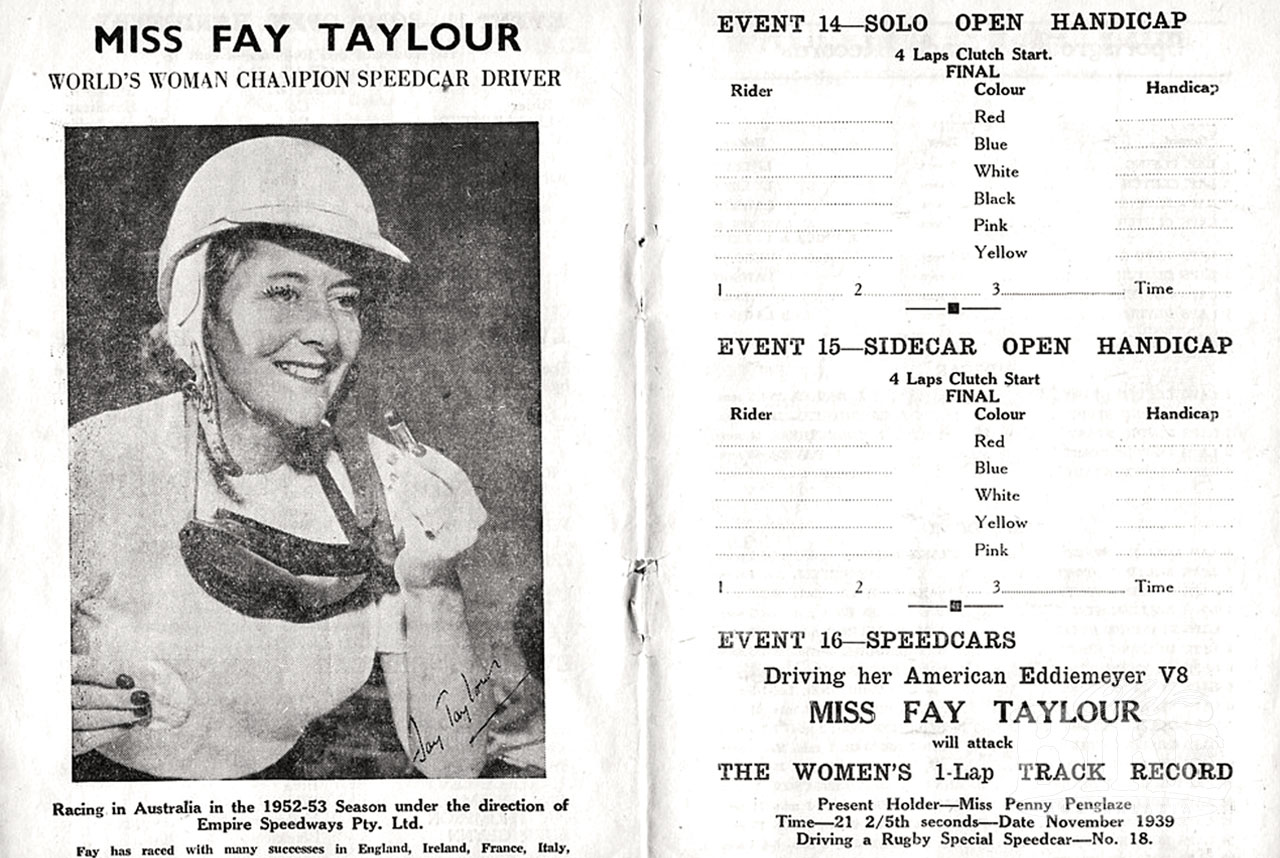

Still as outspoken as ever, she remained under intense scrutiny and following the war’s end, moved to USA. Here she found a new form of speedway racing in Midget Cars, and managed to make a living selling English-made cars from a dealership in Los Angeles. In 1952, she returned to Britain for her father’s funeral but was refused entry to return to the USA – a ban that lasted three years. In time, she even managed to race cars again in Britain, as well as in her native Ireland and in Sweden, and she even undertook another visit to Australia for the 1952/53 season, arriving on October 18, where she raced a midget speedcar owned by Empire Speedways director and former solo star Frank Arthur. On arrival she told the press that she always wears pyjamas under her race suit, which bring her luck and stops her worrying if she should be taken to hospital after a crash. “I detest those prickly hospital regulation nighties,” she explained. The press was also quick to pick up on the information circulated by MI5 regarding her wartime internment, which caused considerable unrest amongst other competitors.

Following the Australian stint she once again went to New Zealand, driving at Western Springs for promoter Jack Cormack. Famously, while in Auckland, she was presented with an unpaid account for a speeding ticket she received during her 1929 visit.

Fay finally retired from motor sport and moved back to England in 1971, but never escaped the public acrimony that remained from her pro-Nazi background. She suffered a stroke in 1982 and died in a Dorset hospital the following year.