From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 87 – first published in 2020.

Story: Peter Smith • Photos: Charles Rice, OBA archives

In the annals of motorcycle sport, there are some famous names behind the names. Bathurst supremo Ron Toombs and spannerman Tony Henderson, Kenny Roberts and his wrench and mentor Kel Caruthers took three consecutive World 500cc titles, Charlie Ogden tuning Lionel Van Praag’s JAP to take the very first World Speedway title in 1936. Add to that list Neville Doyle, who not only guided Gregg Hansford to Grand Prix success, but had a hand in the latter part of the extensive career of Ken Rumble, one of Australia’s most versatile riders.

Neville Joseph Doyle was born at Bairnsdale, in the East Gippsland district of Victoria, in 1937. He attended a local state school and after completing High School undertook a Motor Mechanics Apprenticeship with Marshal’s Garage. In those days it was a 5-year course where one had to be competent at everything that would normally be required of a mechanic, including welding and other skills. Neville’s first bike was a BSA Bantam before upgrading to a 3T Triumph as his ride-to-work machine. His employer allowed him some of the business floor space and he began to sell Triumphs, and after his regular working hours he undertook building engines for race boats, cars and motorcycles. He tells me that this was also to his employer’s benefit as he gained additional knowledge and ability which assisted in his regular work place. This outside work included some of the locals’ road hack and scrambles Triumphs.

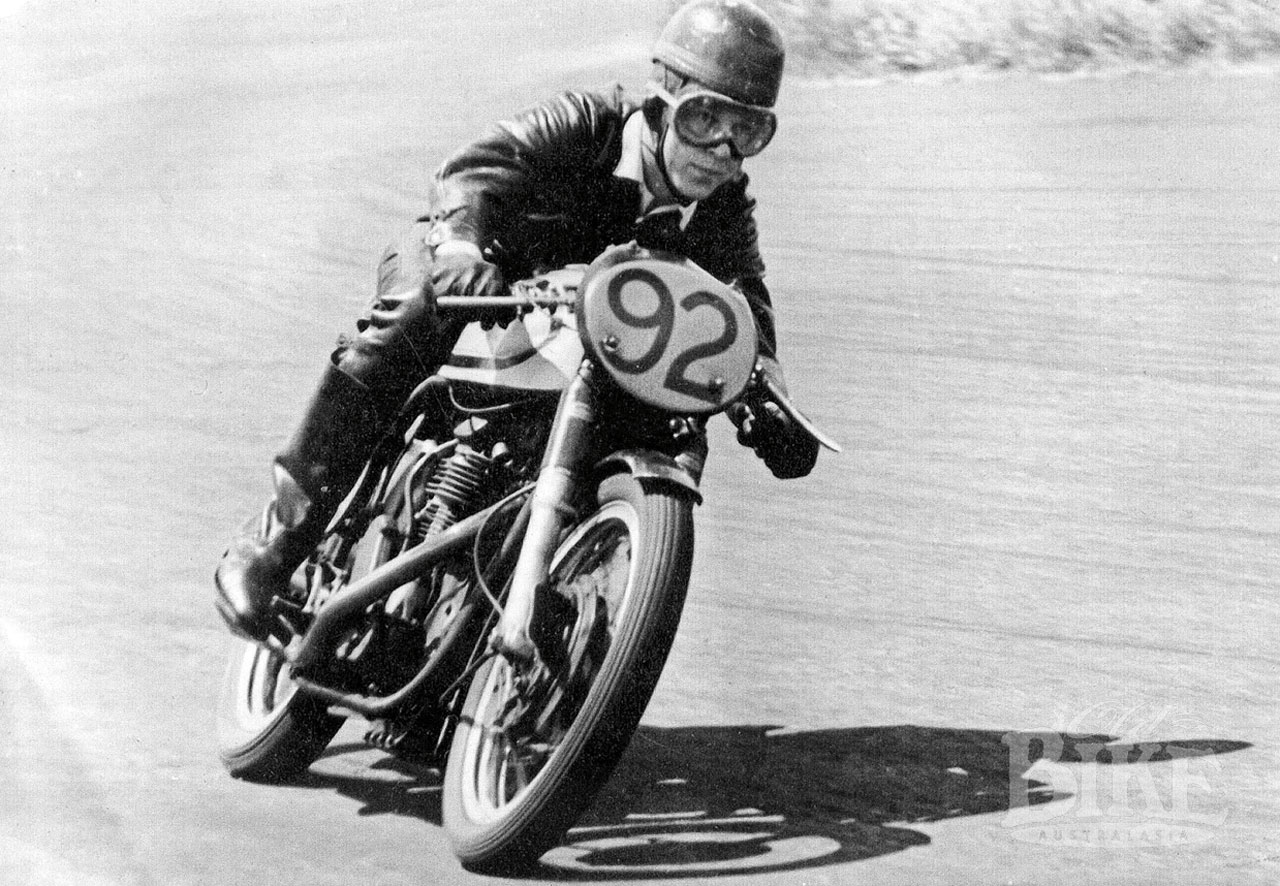

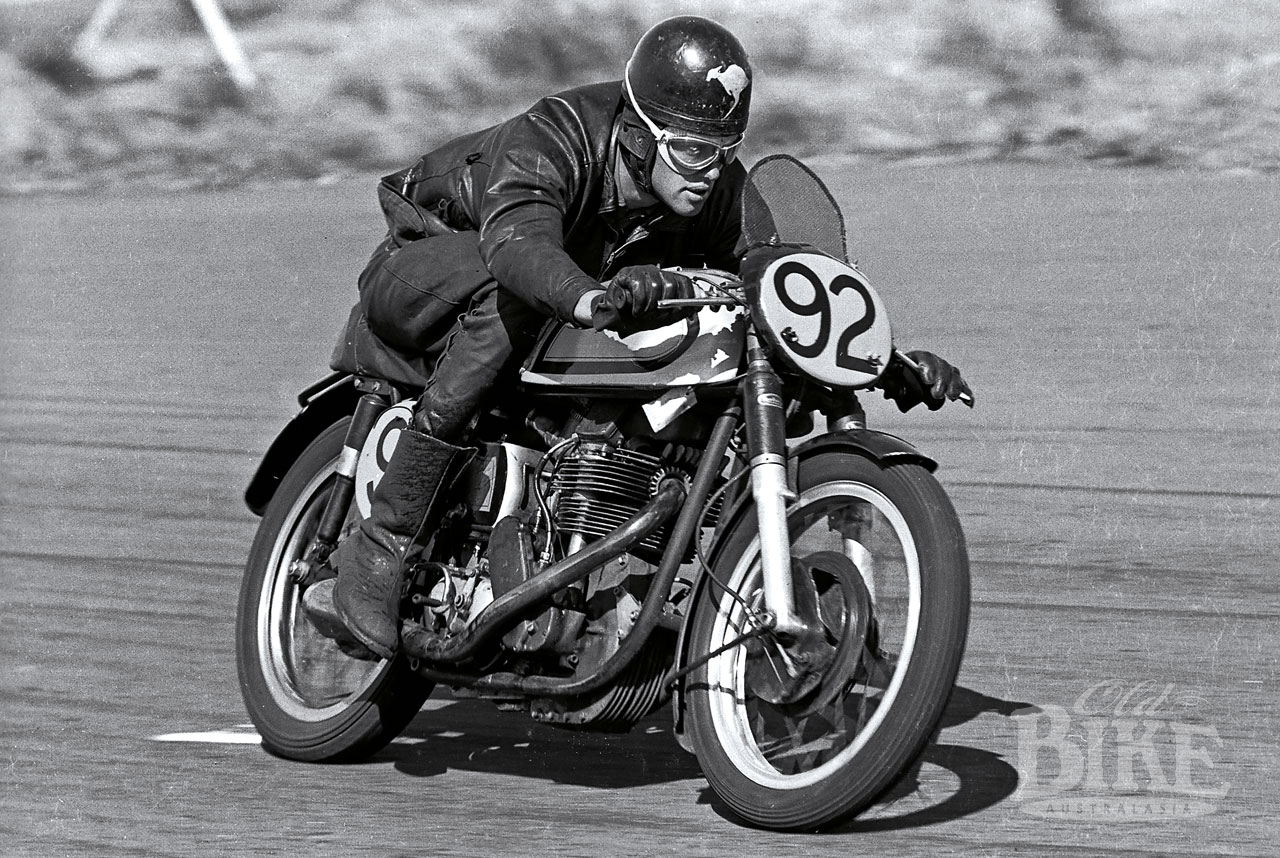

Neville himself raced from around 1954 to 1965 on road race circuits and scrambles and was an A grader in each sport. By 1960 Neville had a Greeves he used in Scrambles and was road racing a rigid framed Triumph. About this time he was working at an engineering business at Lindenow near Bairnsdale. He worked there until the late 1960s attending to water pumps used in local agriculture. During the 1960s he prepared race machines for the likes of Karel Morlang, Ray Fisher, Terry Veering and Ken Rumble. Neville still has the 1935 250 L2/1 Triumph that Rumble won the 1960 Australian Half Mile Grass Track Title on. In the All Powers class JAPs were the big thing at the time but Rumble would go out and just blow them into the weeds on the Doyle 500 Triumph. Rumble, a butcher by trade, was a real gentleman and had ability to ride around all sorts of problems in virtually every form of motorcycle racing. He did not always have to have the best machine but he just knew how to get the best out of them. One Easter Rumble rode a 500 Manx Norton at Bathurst and then drove back to Victoria overnight to compete on the L-2/1 and 500 Triumph at the Warragul Grass Track.

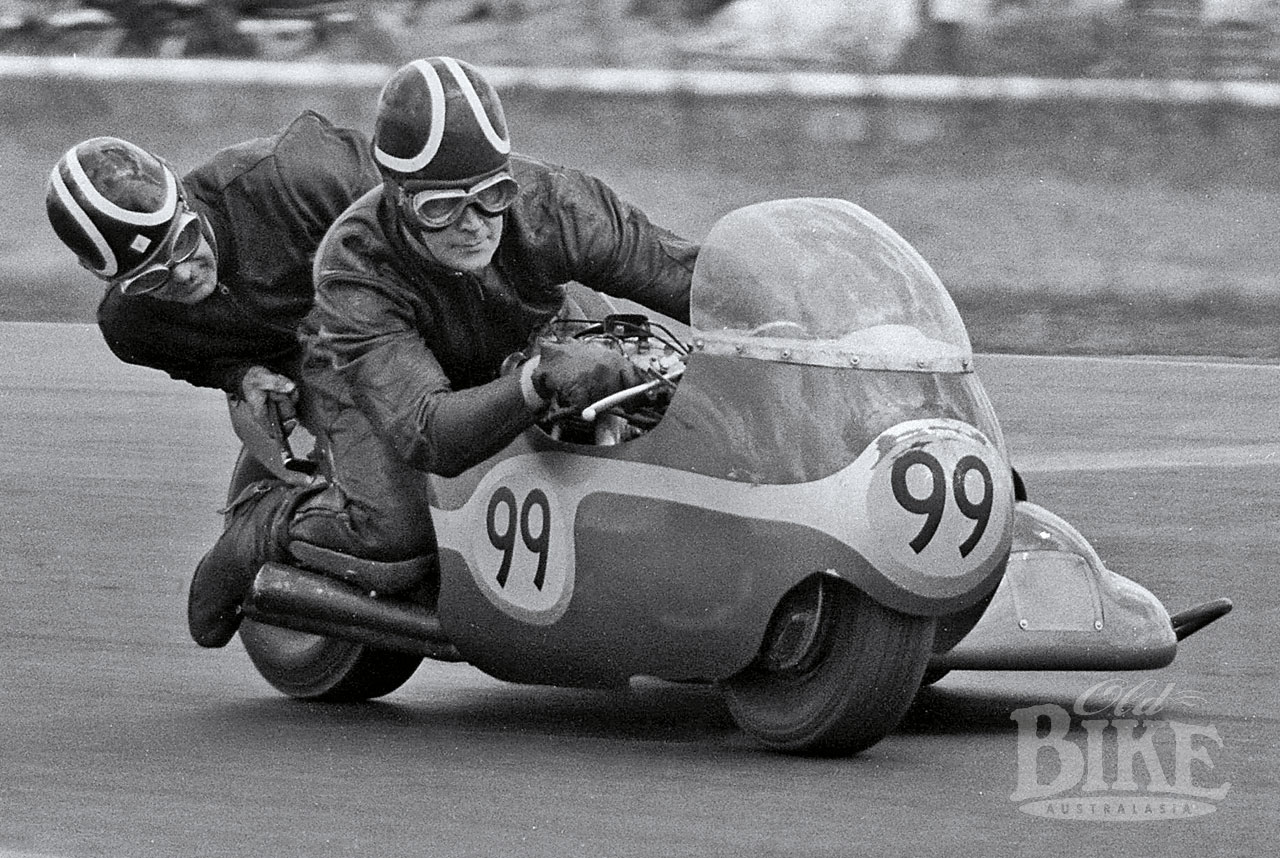

Neville was also good friends with Ray Fisher and prepared engines for his Matchless Metisse and CZ Motocross machines. Terry Veering also rode Neville’s L21 Triumph in Scrambles events in Gippsland and won the 250 championship on several occasions. Terry owned the ex – Maurie Quincey 350 Manx Norton which Neville rode at places like Fishermans Bend in Melbourne. Neville thought the Norton was a fantastic machine. In 1970 he took on a Kawasaki dealership in Lindenow. By this time Ken Rumble had retired from racing solos and taken up road racing sidecars. Neville built a machine for him based on a frame built by Lindsay Urquhart and fitted with a highly developed Triumph T120 engine. On this machine, Rumble won the 1972 Australian Junior Sidecar Championship at Mallala, South Australia, further adding to his status as a legendary all-rounder. In 1973 the Triumph motor was replaced with a Kawasaki H2 750 engine. “It was as fast as I was able to develop it along side the TKA engines,” says Neville. “However Ken had an accident at Hume Weir and broke his leg. I think that he did ride again but by that time I was too tied up with Kawasaki to be involved in other projects.”

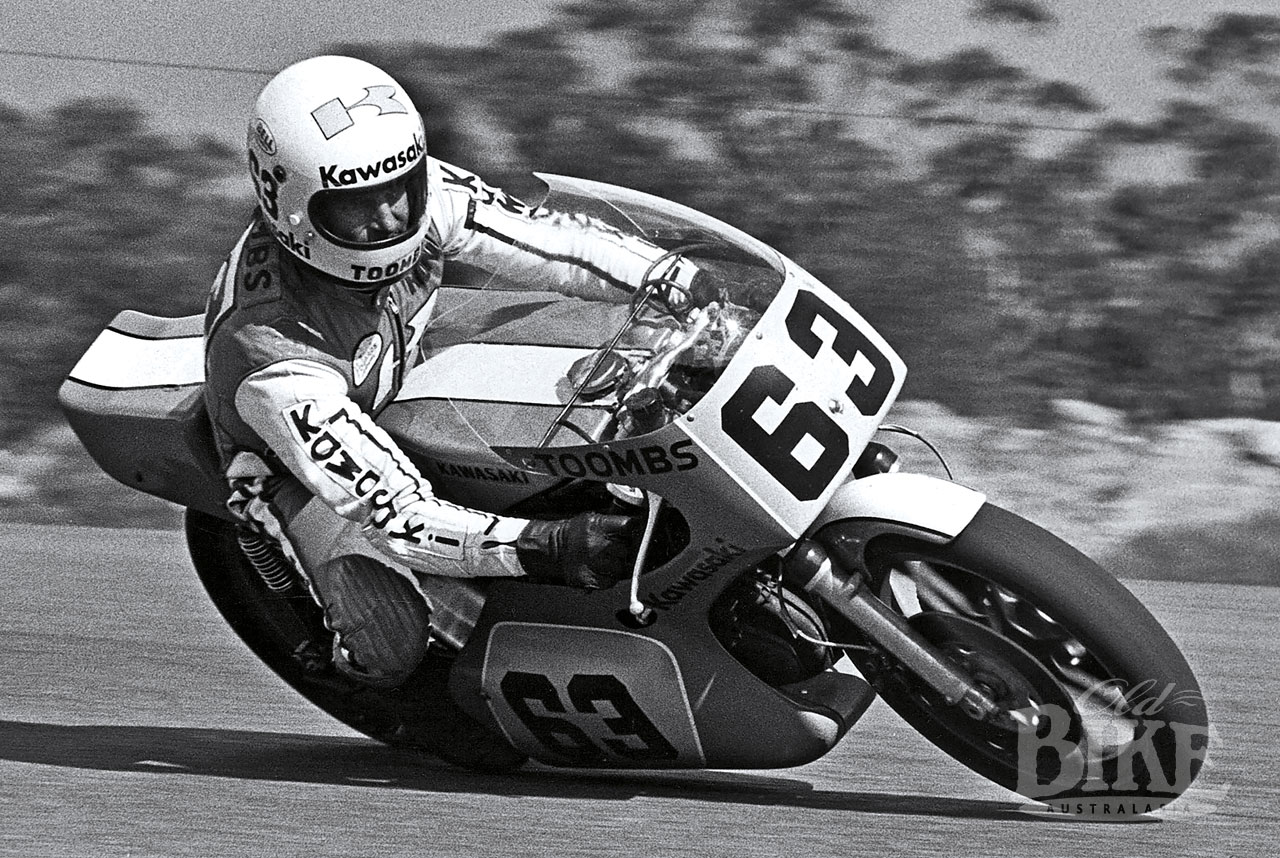

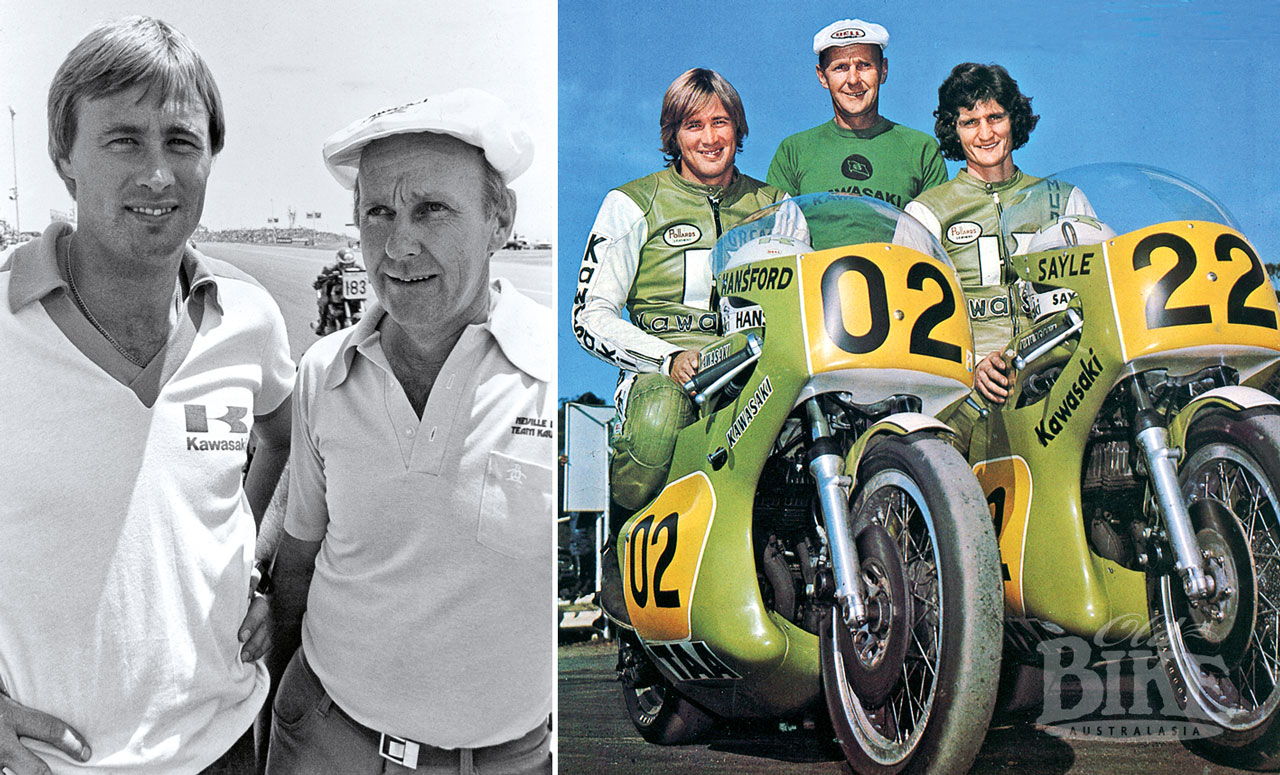

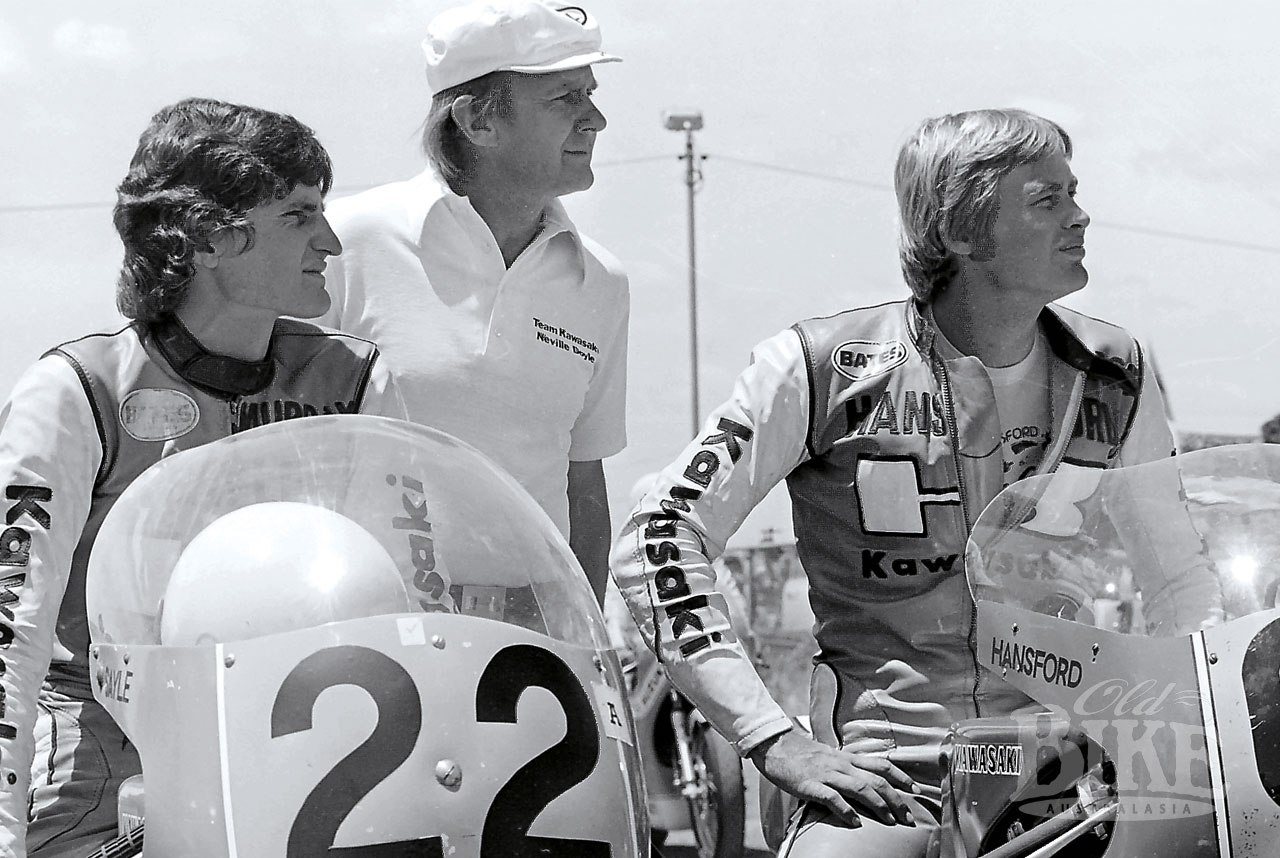

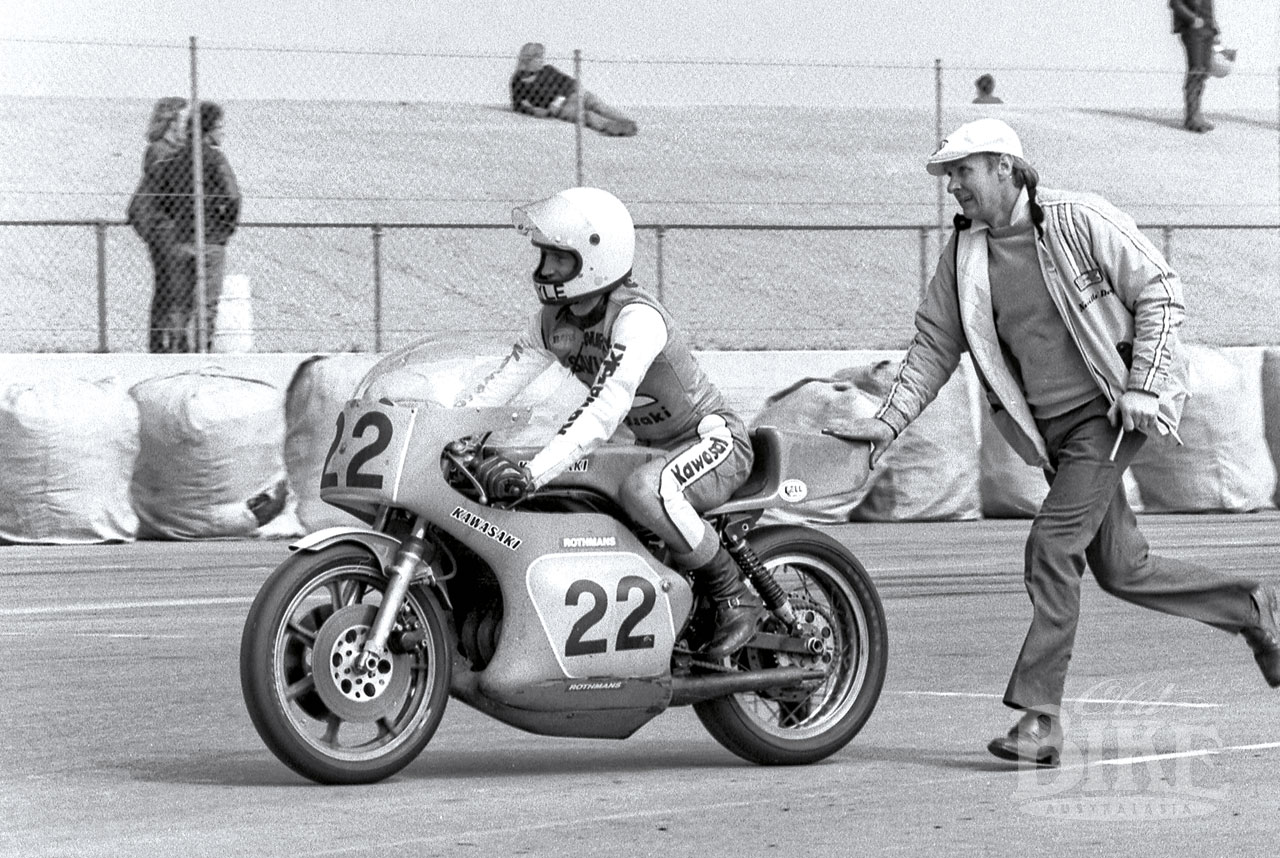

During 1968-70 Neville prepared a 250cc A1R Kawasaki machine for Dick Reid. When Team Kawasaki Australia was formed in 1973, organised initially by Geoff Cook from Toorak Village Motorcycles (the Victorian Distributer) in Melbourne, Doyle assumed the role of Team Manager, while at the same time still running his motorcycle business, Doyle and Shields, which he established with business partner Max Shields. The team was based around the H2R, the air-cooled triple which itself was based on the road-going H2, the first of which arrived in February 1973. Although there was some input and financial support from the Kawasaki factory, the majority was paid for by the local importers. In 1975 Kawasaki Japan took over all motorcycle distribution in Australia and fully funded TKA from that time. Veteran Ron Toombs was signed up as the team’s first rider and Murray Sayle was signed as a second rider for the 1974 season. Ron Toombs crashed heavily at Amaroo Park and retired with serious arm injuries. Gregg Hansford was hired in 1975 and he and Sayle amassed an incredible 29 wins from 31 starts during the season, with Gregg taking the Australian Unlimited title. The first of the water-cooled KR750s arrived in 1976, and a second one for Sayle in 1977. Aboard a Z1 900, Sayle and Hansford also won the Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park in 1975.

Neville recalls the early days of TKA. “The H2R was very reliable provided proper maintenance was carried out. We made extensive modifications to the engines in order to compete with the Yamaha of that time. The early water-cooled KR750 had a problem breaking big end bearings if over revved however the factory made stronger con rods after the first year and from that point a rev limit of 11,000 was safe. We made new crankshaft seals to improve oil flow to the big ends which also improved the reliability and life of the crankshaft. The first of the KR250 (tandem twin) machines was ridden by Murray Sayle and proved to be very competitive. However the engine had a 180-degree firing order and suffered vibration problems. For 1976 the factory made a completely new model which included a new Unitrak suspension and a 360-degree firing order engine. For the 1978 GP season the factory supplied completely new KR250 and KR350 machines. We had five machines in all however there were some problems with the crankshaft bearings which did not show up in the limited testing time we had. However the factory rectified that problem within a month. Most of the time the factory kept on top of any problems. For models up to 1979 the cylinders were all one piece. Then from 1979 they used separate cylinders but we did not have those models here. For the 250 and 350 I undertook some engine modifications, however they were pretty good as they were. I did change the valves in the forks to alter the damping and fitted Koni special rear suspension units to provide a wider range of settings. In addition I fitted twin front disc brakes to both the 250 and 350. Then in 1982 the factory dropped the 250 and 350 machines so as to concentrate on the KR500.”

In the early ‘80s Kawasaki moved its operations to Sydney although the team workshop stayed in Melbourne. The team also ran production machines in events such as the Castrol 6 Hour Race at Amaroo Park. Later riders included Len Willing and Jim Budd with Willing crashing with just ten minutes left of the 1985 Six Hour at Oran Park when well in front. In the late 1970s and early 1980s Jim Budd also rode Superbikes for TKA.

After a few exploratory events in USA and Europe, in 1978 the team’s focus shifted fully to the international scene with Hansford as the sole rider, using KR250s and 350s, and the KR750 in the FIM 750 Championship. “The first Grand Prix meeting we did in Europe was in Spain in 1978,” recalls Neville. “There were complications as he had no previous racing history over there so the officials initially refused him permission to ride. Hectic phone calls were made including back here to Ian Cameron, Secretary of the ACCA. Permission was eventually granted and he went out in the last practice session and was the quickest. He then came back and told us what he wanted with regards to gear ratios, suspension and other factors so as to get the maximum performance. He was just so good at being able to identify and tell us what he needed to win. He went out in that race, the 250 GP, and won.”

For Daytona in 1978 Hansford rode in the 100 mile 250cc event on a KR250. He diced with Ron Pierce on a 250 Yamaha when the lead changed 35 times in 26 laps. Pierce had the horsepower but Hansford, although a larger build, out-braked him. This was mainly due to Neville having fitted 750 brake components which included a twin disc setup. Revs Motorcycle News reported on Hansford’s winning ride. “The previous year Hansford had out-braked Kenny Roberts, Franco Uncini and Steve Baker. Hansford showed Pierce time after time that he was quite willing to – and capable of – going far deeper and harder than his opponent to make up for any lack of sheer top end speed. ‘I just can’t brake any harder – it won’t stop any better’, Ron Pierce told Steve Baker before the start of the 250 race. ‘Hansford just keeps getting me going into the turns.’ ‘I know what you mean’, answered Baker. ‘He kept doing the same thing to me last year.’ Hansford’s machine had a problem in that it kept jumping out of 4th gear. However Pierce destroyed his brakes trying to keep Hansford at bay.”

Although many recalled the 1974 dice at Bathurst between Hansford and Warren Willing as being a most memorable event, Neville’s recollection of these two riders is one race at Oran Park on 750 machines when Hansford took over the lead on the second last lap. “In 1978 we were having trouble obtaining suitable tyres for the 750. I designed new magnesium wheels which were cast by Campagnolo in Italy. That allowed the use of a wider range of tyres. In 1978 and in 1979 Gregg finished second in the 250cc and third in the 350cc World Championship. All up he won 10 World Championship Grand Prix races, plus the Canadian round of the Formula 750 world championship.”

Despite the international success, things were changing, as Neville recalls. “In 1980-81 we did not compete on a regular basis but continued testing machines overseas. Gregg also won the Australian 250 and 350 Grands Prix at Bathurst. Whilst we were absent overseas Rick Perry rode a KR350 and got an Australian Title. Those machines could do a whole season without much trouble. He only had to look after tyres and other odds and ends.”

Meanwhile Kawasaki was working on a project to take them into the 500cc Grand Prix class – a square four two stroke. 1981 saw Neville make several trips to Japan and give suggestions to Kawasaki as to what we needed. “Gregg tested a current model 500 in Japan and gave his opinion as to what he required. Kork Ballington, the South African who won four world championships on the 250/350 machines also rode the 500 but with limited success. In 1982 Tony Hatton joined the team as a mechanic for the European season. We only ran the one machine, a 500 and were concentrating on that when at the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa Gregg overshot a corner and hit a flag marshal’s car and broke his leg. He was hospitalized and when discharged he flew home which resulted in a blood clot in the fractured area. He did not race motorcycles again but concentrated on car racing and (with Colin Bond) won the Bathurst 1000 in 1993. Unfortunately in 1995 he was involved in a fatal collision at Phillip Island.”

In 1988 Neville stepped down from managing Team Kawasaki and his son Peter took over his role. Peter later went to America and managed Matt Mladin who was multiple American Superbike Champion riding for Yoshimura Suzuki. Neville explains that he found two strokes different and thus he treated them differently. Although it is difficult to explain, two strokes were still going up in power at the time when four stroke development progressed even further. “They are both pumps. Water pumps are similar as it is all related to efficiency. How you arrive at the end result is different,” he says. Neville learnt a lot by trial and error. The early days with the Triumphs toying with E3134 cams, an independent cam for inlet and exhaust and with the three-keyway cam wheels gave him the opportunity to vary the timings and assess the results. This then taught him how significant that valve timing factor became in engine performance.

Some time ago Neville made a statement that “Racing is in a constant state of development and I’m still learning new things every day. Although I have 25 years (that was then) of background experience behind me, eight of those with semi-works or full race works machines, I still have as much again to learn. Even now I learn as much every day as I did those 25 years ago. I doubt if there is any limit.” In his younger days he was reading up on as much material as he could muster. He further states, “There was and still is a lot of work published on the aspects of tuning but I quickly found then, and still find now, that much of the information is five years out of date. In other words books published in five years will be explaining what we are doing now. So once a basic understanding has been completed, tuners like myself are working in largely unknown areas developing our own ideas. Most of my work has been trying to achieve harmony. In many ways it is like a jig-saw puzzle. One factor naturally influences several others and where improvements are on the verge of being successful maybe half a dozen others have to be changed to gain the most benefit. The rate at which theories can be examined and rejected can be astonishing.”

Neville went on to say back then that, “Theories of just two months may no longer be valid in the light of subsequent research. We are still working largely in the unknown which is why there is such a variation in ideas and practice. Two engines which were originally identical may have been worked on in developing two sets of theories and may differ markedly in a number of major factors such as port and carburettor size, timing, exhaust pipe shape, length and diameter – yet have identical top end speeds. Contrary to what seems to be generally thought we do not have a special magical exhaust pipe shape. Certainly it is an important part, but only as part of the integrated whole.”

When talking about or watching a successful racer, it is important to bear in mind that although they have exceptional skills and determination, very often there are people behind the scenes with the knowledge and skill to develop machinery that allows the rider to successfully compete at the very highest level. Such a man is Neville Doyle; innovative, practical, and modest to a fault.