From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 94 – first published in 2021.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Mick Lendrum and OBA.

No, Motoplast is not a special adhesive bandage for motorcycle injuries such as severe gravel rash. From Soncino, a province of Cremona in the Italian region of Lombardy, 60 kilometres east of Milan, Motoplast was a short-lived creation from the brothers Virginio and Gianfranco Stanga.

As the name suggests, their company was originally, and primarily involved in the production of ‘plastic’ (including fibreglass) bits and pieces as after-market components for a whole range of motorcycles; big Japanese road burners and home-spun products from Laverda, Benelli, and Moto Guzzi. There were also items for smaller fry like Morini and Jamathi. These parts included complete tank/seat units, fairings, mudguards fuel tanks and seat bases. By the late ‘seventies, the brothers had a workforce of around 15 in their factory, and with this production paying the bills, diversified into metal products such as exhaust systems, various milled alloy brackets, swinging arms and complete frames. Virginio Stanga was also a handy racer, competing on his own products in events such as the Bol ‘Or and other European Endurance events.

In Australia at the time, there were few bods more committed to Italian motorcycles, particularly Ducati, than Ian Gowenloch. A habitué of the annual European motorcycle shows in Milan and Cologne, Ian kept an expert eye on what was around, or in the pipeline. In the early ‘eighties, he spotted Motoplast’s offerings in a Milan Show catalogue and decided to order two kits to accept Kawasaki 900 engine units.

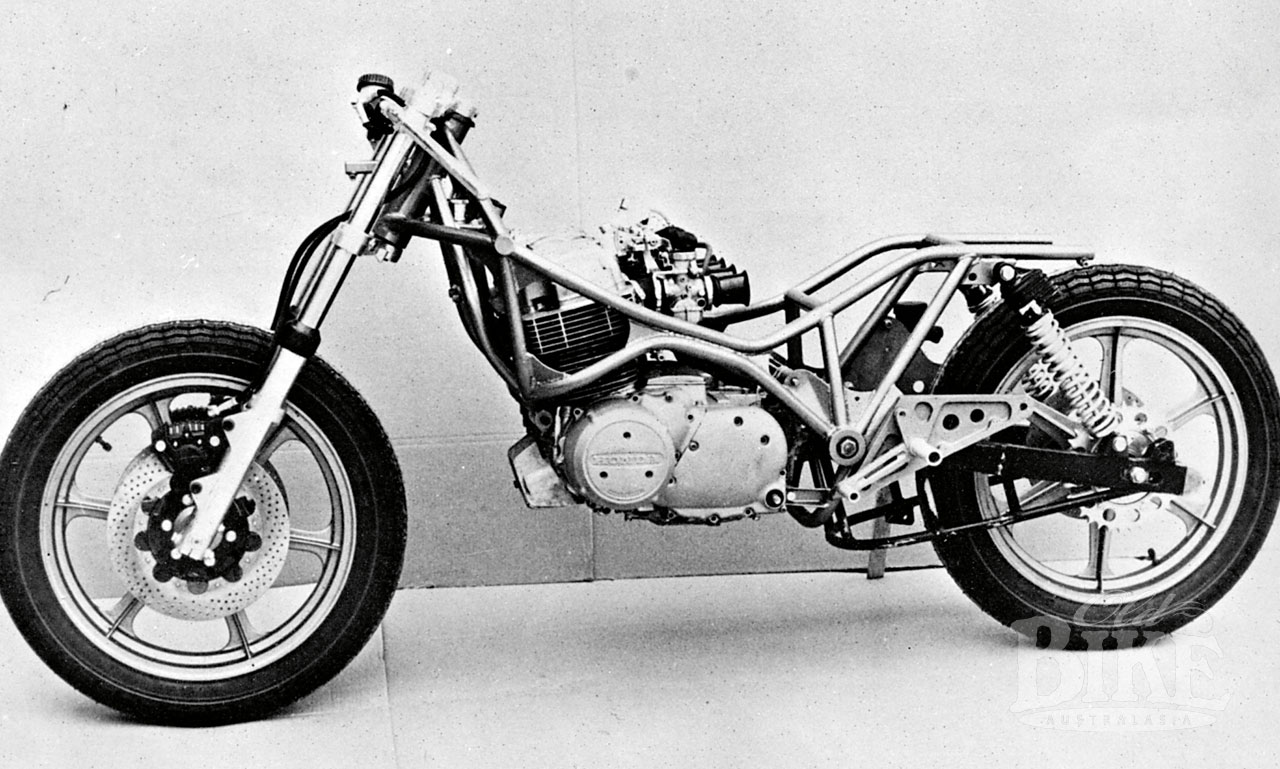

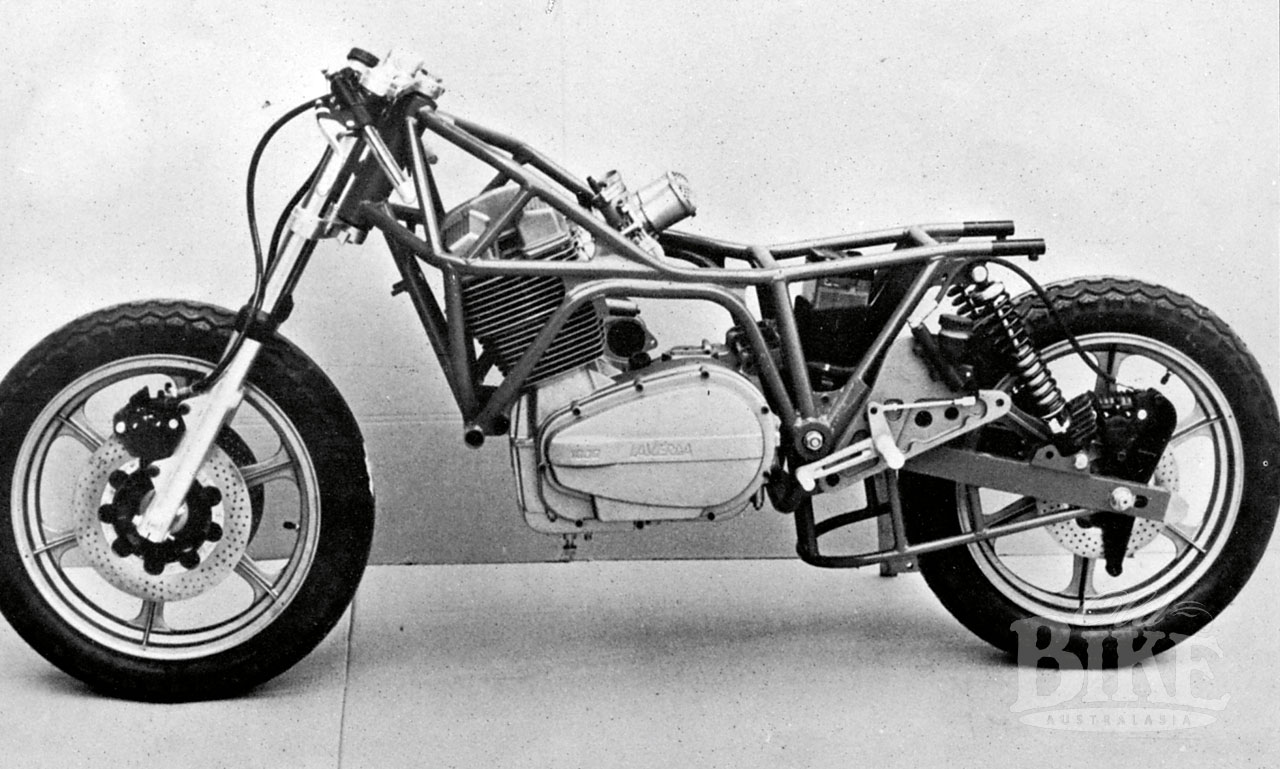

The first of these arrived in time for the Sydney Motorcycle Show – the first stand-alone motorcycle expo devoid of the usual car component – held at the Bankstown Civic Centre in March 1982. Manufacturers large and small snapped up the 50-pdd stands available, displaying motorcycles and a bewildering array of accessories. On the Gowanloch stand sat the Motoplast with its curious and voluptuous twin-headlight fairing and equally extravagant tailpiece/seat, wrapped around a Kawasaki 900 engine. The price quoted for the Motoplast kit (less engine and a few other components) was a not inconsiderable $3,600 which included the frame, seat, tank, Paoli monoshock, Marzocchi forks, Brembo discs and calipers.

One of the two bikes was sold and the other retained as a demonstrator. Ian even had ideas of running it at Bathurst in the Arai 500 Endurance Race, but this plan was aborted in order to concentrate on getting their special Ducati to the line.

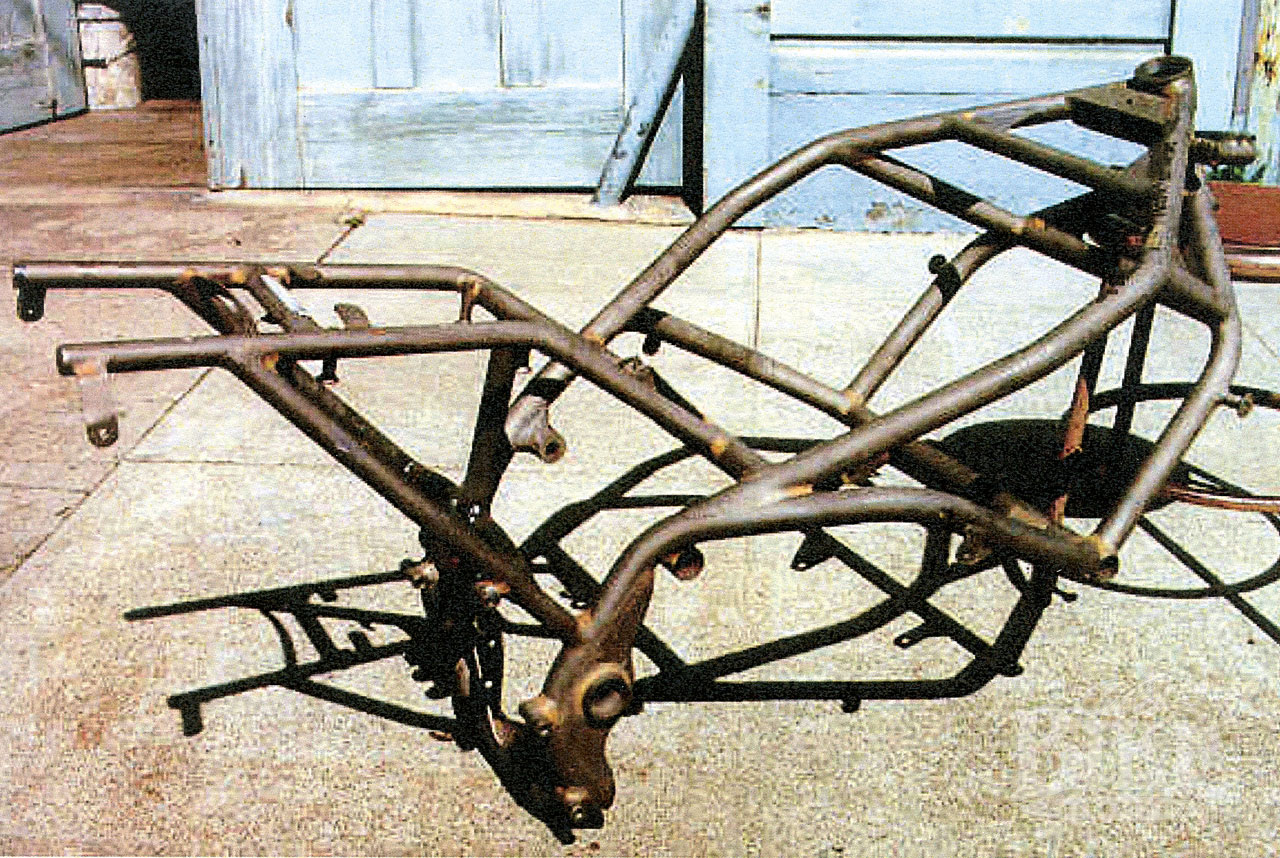

The heart of the matter, the frame, was built from 37mm thin-walled chrome-moly tubing, and the fairly standard Z1 engine fitted with 34mm CDC Mallossi carburettors. An all-up weight of 191 kg was quoted, which wasn’t too bad considering the tank contained 24 litres of fuel. The massive tank and the equally voluminous tail fairing left precious little space on the single seat, which had apparently been scaled to suit a trim Italian posterior. Wheels were Ducati-style aluminium-silicon alloy, and the cast iron discs with electron carriers gripped by the very best Golden Line calipers from Brembo, with Mintex pads and braided steel brake lines. Motoplast’s own four-into-one exhaust system produced a highly anti-social scream.

By the time the sums had been done correctly, allowing for the fairly unhealthy state of the Australian dollar at the time, the projected cost for the basic Motoplast kit had risen to $4,500 – more if the buyer wanted really trick proprietary components – plus of course there was the matter of supplying your own engine, wiring, instruments and a few other items. Not cheap.

Still, Gowenloch reckoned there was a market here, albeit a limited one, and decided to order nine more kits; five to take Kawasaki engines, two for Suzuki GSX1100, and two for the CBX1000. It transpired to be a labour of love, as Gowanloch and subsequent customers faced plenty of problems. Not the least of these was the inconsistencies between each frame, where the mounts seldom lined up when installing the engine. It made the process tedious and expensive in terms of labour, and despite complaints to the Italians, it was never really rectified. Calls to Motoplast went unanswered until eventually it was discovered that the company had abandoned frame making to concentrate on exhaust systems. One source says that a total 72 frames were built up to 1983.

Motoplast Mick

A name synonymous (in Australia) with Motoplast is Mick Lendrum, a long-time member of the Sydney motorcycle trade who is now based in the NSW Southern Highlands. It was a chance conversation with Ian Gowenloch that led to what has become a mild obsession with the curious Italian marque.

“My ownership of the bikes came about when I was talking to Ian and he mentioned that he no longer wanted the four remaining unsold frame and bodywork kits,” says Mick. “One was a rolling chassis with bodywork which turned into the bike I now race. Two of the others were also kits to take Kawasaki Z1 engines, which I sold. After a few years I now have one of those back, which is another project for some time in the future. The other Kawasaki kit I think is in South Australia with possibly a Z1000J motor being fitted. The fourth went to, I believe, a shop to have a different motor fitted, possibly a CBX1000. That one, at least the frame, is now hanging in my shed.”

Mick has become a familiar figure on his Z1-engined Motoplast at race meetings at Sydney Motor Sport Park and Wakefield Park in Goulburn, and not surprisingly, his race bike is an ongoing commitment. For the 2021 OBA Classic Challenge at SMSP, Mick worked long and hard to upgrade the front end, chasing better steering and stopping. Although the meeting was ultimately washed out, Mick did get some laps on a wet track during Friday’s practice – not an ideal situation in which to test the new parts, but better than nothing.

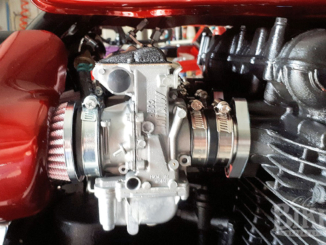

Having a frame kit is one thing, but then it’s up to the individual to craft the complete machine, a challenge that Mick relished. “The engine is 1103cc with Yoshimura Road and Track cams with 29mm Mikuni smoothbore carbies, with a factory close-ratio gearbox that I got from Ric Andrews after swapping said gearbox out of a second hand bike from the floor of his old shop (in Waitara). The motor came out of a road bike and is a bit tired but there is a new top end about to go on with a set of 33mm Mikuni smoothbores which will give it a new lease of life.

“The electrics are total-loss using a small battery next to the oil catch tank in the seat hump and the harness etc is all home made. Starting is by standard starter motor using an Anderson plug to a remote starter battery. The rear shock is a “tricked up” FZR1000 shock, I believe, and the tank is fibreglass that now holds fuel due to major help from Brett Rosenthal whose V7 Sport Guzzi was featured in OBA issue 26. The rear sets are from an Aprilia Falco – because I have one and that is handy for spares. The tank stickers were designed from originals and made in America from files developed by Brendan O’Donnell from Corvuscreative.

“The front forks that were (at the time of the photography for this article) 38mm Marchozzi using Marchozzi Guzzi sliders to be able to use the Brembo 08 Gold Line calipers without adaptors. There are Brembo rotors on a Bimota wheel that had the correct PCD. The rear wheel is a Yamaha TRX850 using the standard Yamaha rotor and there is a Brembo 05 caliper on a home-machined floating mount. The muffler I made myself as I wanted to have a secondary pipe diameter of 2.1/4″ and hell, why not make it all myself.

“The new front forks are Yamaha TRX850 with the New Zealand-made Sports Valve emulators. The front wheel is Aprilia Falco cause I had a spare and the axle size has been changed to 20mm and there has been a new axle machined to suit. Rotors are MetalGear TRX850 that have the same PCD as the Brembos used on the wheel, with spun alloy rotor carrier covers to give them the correct “look” for P5 class.

“Some time ago I managed to get hold of a set of the quite rare P432 Brembo calipers, which are 4-piston calipers that are the only 4-spots legal for the Period 5 Unlimited (Forgotten Era) class. The 32 part means 4 x 32mm pistons, rather than the Gold Line calipers which used two 30mm and two 34mm pistons. The P432s were a hot set up for early ‘80s racing bikes. Michael at Gowanlochs helped with sourcing the correct seals for the calipers at the last minute. There are machined adaptors for those to fit the TRX forks.

The new forks required a new front guard, which I did not have time to paint so it looks a bit out of place in orange/yellow, but that will be fixed.”

“There is bound to be more of the Motoplast story out there, so if anyone wants to share information, I would be pleased to hear from them by email on motoplastmick@gmail.com”

One from the west

Versatile WA racer Tony Hynes rides everything from pre-war Vincents to modern Superbikes. In his stable is possibly the only Motoplast in the state, fitted with a Suzuki GSX engine.

“I got the bike in 2012 from Noel Twiss. He got it from Eurobrit in Melbourne sometime before that,” says Tony. “I have developed the bike since then. 17-inch wheels, Ohlins rear shock, and engine work done by Lloyd Pearce at Gelorup Motorcycle Repairs. It has 141 horsepower from 1166cc. It’s a great bike to ride and handles brilliantly. It has been on the podium twice at Australian Historic titles and still has the lap record for P5 Unlimited at the Collie short circuit.”