From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 85 – first published in 2019.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: OBA archives, Elwyn Roberts, Alan Wallis, *Letter kindly provided by Joe Henry.

With the death of Ken Kavanagh in his adopted home of Bergamo, Italy in November 2019, a chapter closed on the life and times of the most consistently successful Australian rider of the ‘fifties, notwithstanding Keith Campbell’s 1957 World title.

Following the 1951 Isle of Man TT races, the cruel British motorcycling press nicknamed TT debutant Kenrick Thomas Kavanagh “Last-Lap” Kavanagh by virtue of the fact that he had lost fifth place in the Senior TT when his oil tank split on the final lap. Things would, however, improve, and quickly.

Ken was born on 12th December 1924 in Melbourne, and left school at the age of 15 to commence an apprenticeship with brothers Rod and Col Sampson at their motorcycle business in Camberwell Road, Hartwell. He had scarcely taken up tools there when the war broke out, and the enforced curtailment of racing temporarily also curtailed his plans to forge a racing career. By early 1944, the local scrambles and trials scene had restarted in a modest way, with activities restricted due to a critical shortage of petrol. Ken joined Hartwell club and on an ancient side-valve 500cc AJS loaned to him by the Sampsons, took his first steps in motorcycle sport. But scrambles held little interest, “My only passion was road racing, above all, way above all, the T.T. – the Isle of Man. I knew that I could never settle down until I’d seen a T.T.”, said Ken in a letter* to Linden Sampson (Col’s son) in 1995.

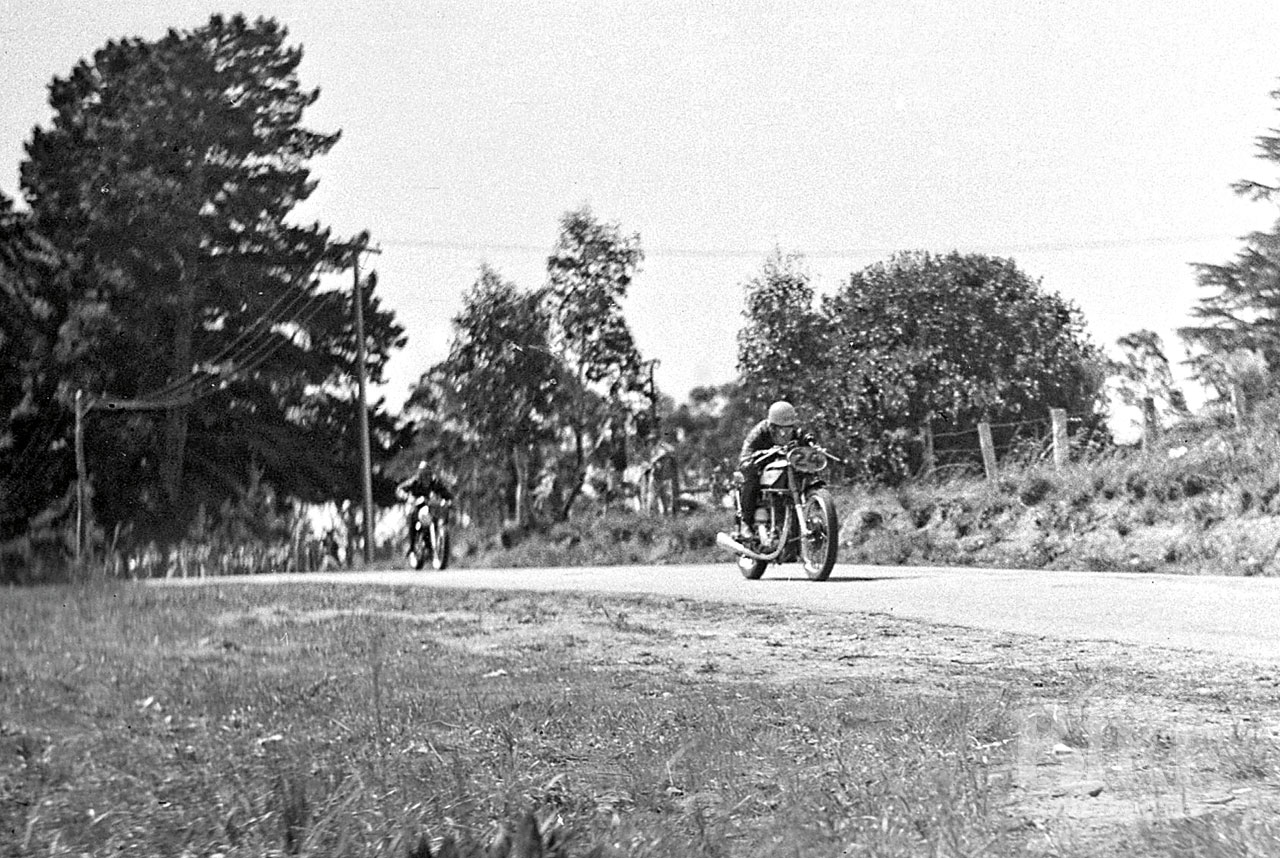

The problem was, there was no road racing in Australia – until New Year’s Day 1946, when the sport began again at Victoria Park, Ballarat. Ken was desperate to ride, and eventually wore down the Sampson brothers to allow him to ride Col’s own Ariel Red Hunter, which was in scrambles trim. After feverish activity, the Ariel was converted with a larger capacity oil tank and other mods – the work completed in the evening of December 31st, just in time for a quick thrash up Dandenong Road to try it out. The next problem was how to get the Ariel to Ballarat: 120 km away. The local bakers volunteered the use of an old V8 Ford ute, which was fine except the gearbox wasn’t working, but by midnight that had been solved provided someone held the gear lever tightly to prevent it jumping out of gear. With six people aboard (Ken and two others in the tray with the Ariel) they were finally ready, only hours before practice was to begin. “It was just starting to get light when we got onto the Ballarat Road outside Footscray, and here we are going to our first T.T.” recalled Ken.

By some small miracle, Ken and the Ariel (“not just any Red Hunter, but Col Sampson’s Red Hunter!”) were on the line at Ballarat, with their sights set on the Clubman’s TT. It was to be a fight from go to whoa with his arch enemy Jack French (“He thieved my girl friend, Betty, the prettiest little blonde that ever lived, and I hated his guts”), the pair pushing and shoving for the whole race. “I’d come by him at over a hundred MPH and shoulder him across the road. We ran off the road so often it just wasn’t funny”. By the last lap Ken had pulled a fifty yard lead but then ran off the road into a gutter, and while extracting himself French motored by to win. “I carried on with a red face to lose the race, the most important race of my life”. By the time the entourage arrived back in Melbourne, Ken had not slept for two days and two nights. “At Melton (on the way home), the boys stopped the ute at the Golden Fleece Hotel, it was run by George Hannaford (former top racer and Isle of Man rider), for a drink. Me, no, I don’t drink. They all fell into the bar, but I stayed there with the Red Hunter. I sat in the back of the ute looking at the Red Hunter, we couldn’t abandon a friend at a moment like this. I wasn’t to know what would happen in years to come. I would ride Works Nortons, would ride for Moto Guzzi, would become the rider that made the Moto Guzzi V8 famous, ride the MV, but the only motorcycle I remember with affection, a motorcycle that would never hurt a rider, was Col Sampson’s Ariel Red Hunter.”

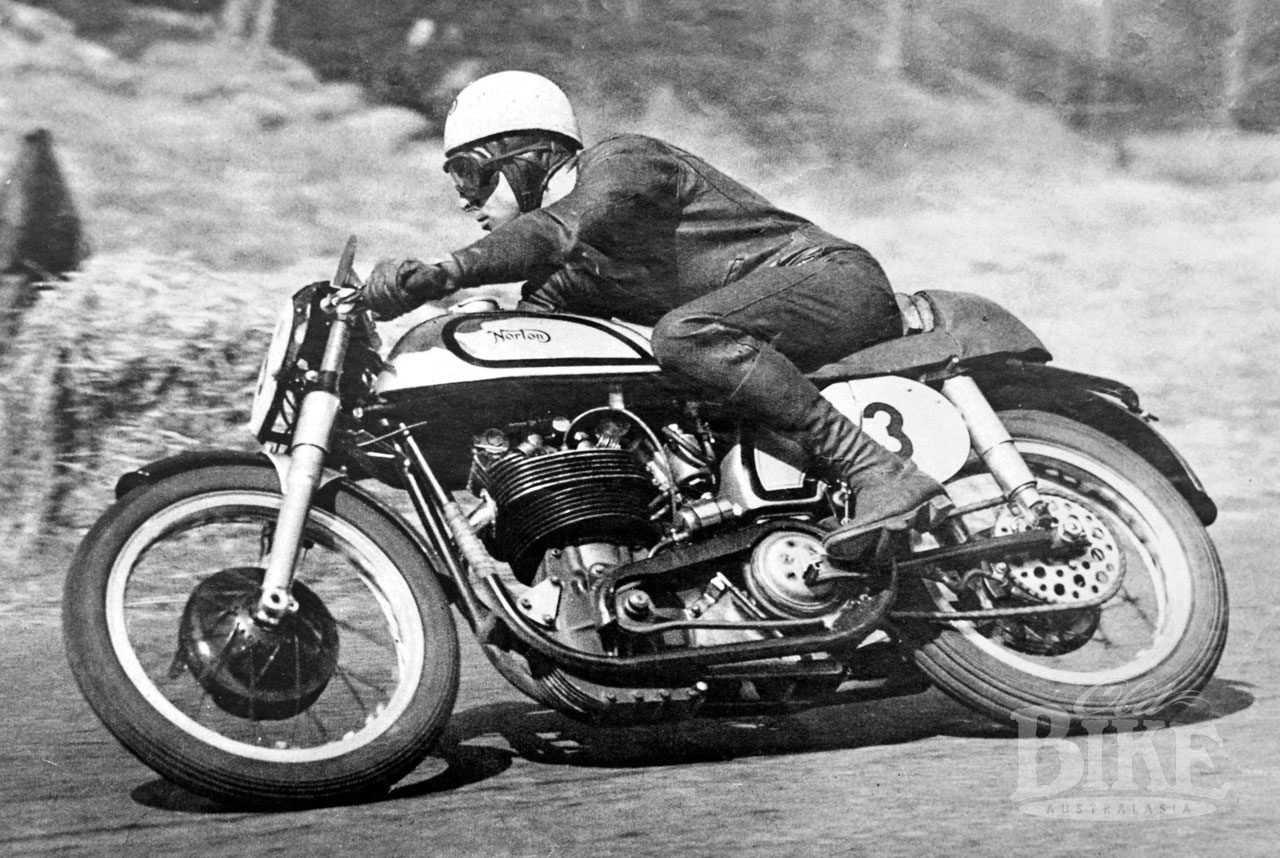

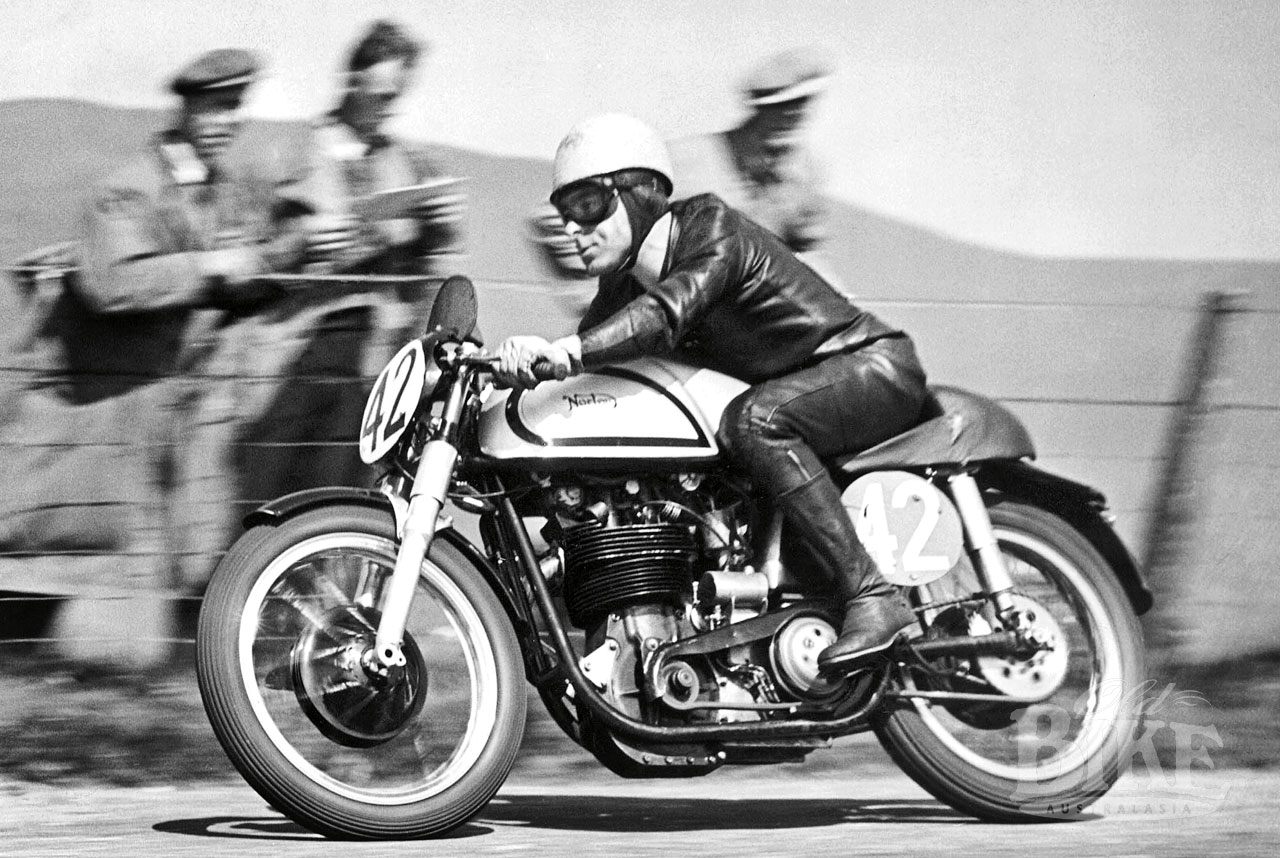

With his appetite for road racing well and truly whetted, Ken chased rides, and with financial assistance from his girlfriend’s father, onto the first new post-war Manx Norton to reach Australia, imported by Norton agents Disney Motors. It was a ‘Garden Gate’ plunger frame model, but it was fast, and took him to wins in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania before being replaced with a later model double overhead camshaft version.

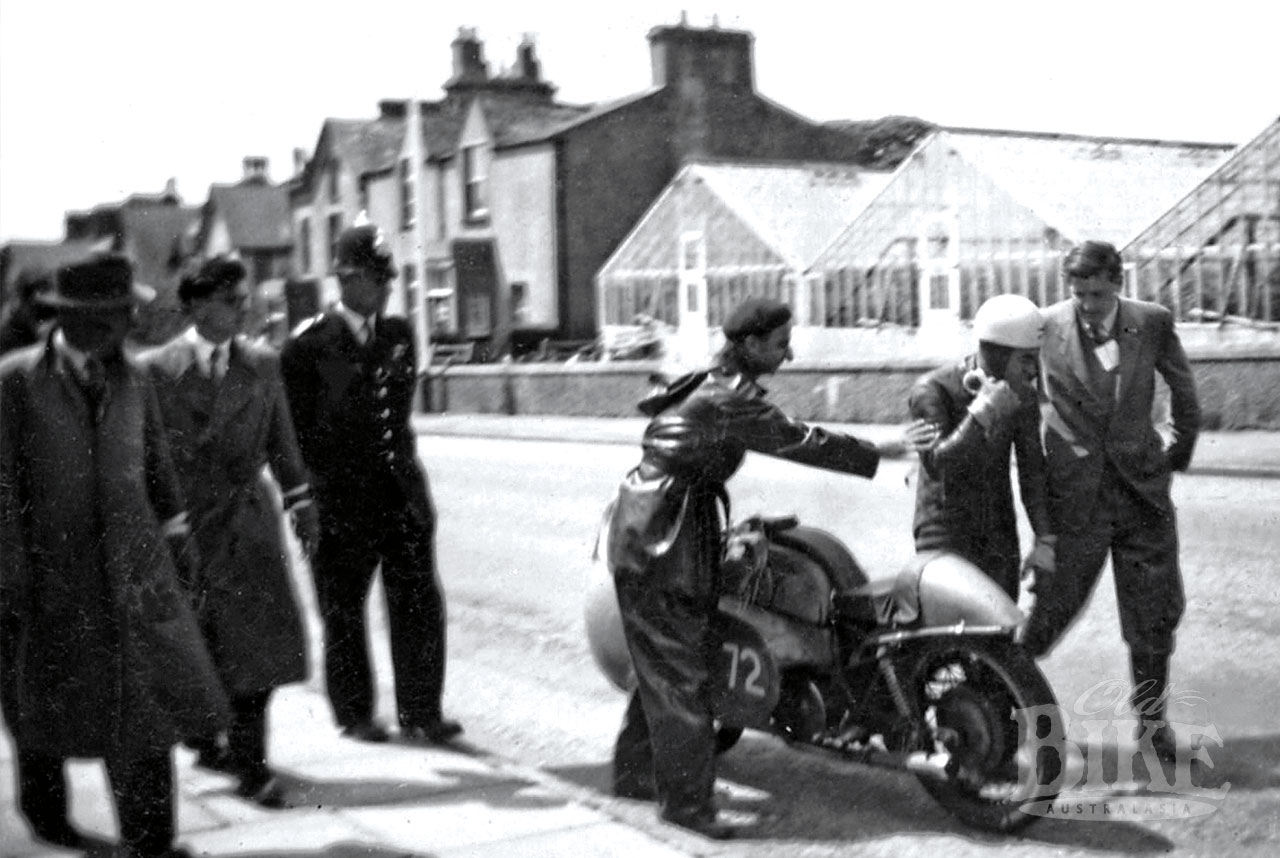

When Australia’s official team for the 1951 Isle of Man TT was announced it contained three names: veteran Harry Hinton, Tony McAlpine (who had shot to fame aboard a Vincent twin), and young Melburnian Maurie Quincey. The latter however declined the nomination, preferring to stay at home to concentrate on the motorcycle shop he had just opened, so Ken received the nod. His employers, Disney Motors, arranged for a position at Norton Motors in Birmingham, but it was menial work on the production line for the new Dominator twins. Disneys also ordered a pair of Manx Nortons – the brand new model with the soon-to-be-legendary ‘Featherbed’ frame – and Ken took one to sixth place at Goodwood in his British debut. Two days later, he and the Nortons were sailing to the Isle of Man, which was still five weeks away. He spent the time doing endless laps of the 37.75 mile circuit before lining up for the Junior (350cc) TT. After three laps he was holding an impressive 11th, but his engine quit and he was out. It was the race where Harry Hinton, aboard a works Norton, suffered a major accident and injured himself quite severely, whereupon Norton team manager Joe Craig offered Ken Harry’s works 500 for the Senior TT later in the week. It was tempting, but after consideration, Ken declined the offer, saying, “I said that the (production) Manx bike was so far fast enough for me, and I doubted I’d do justice to a works job yet.”

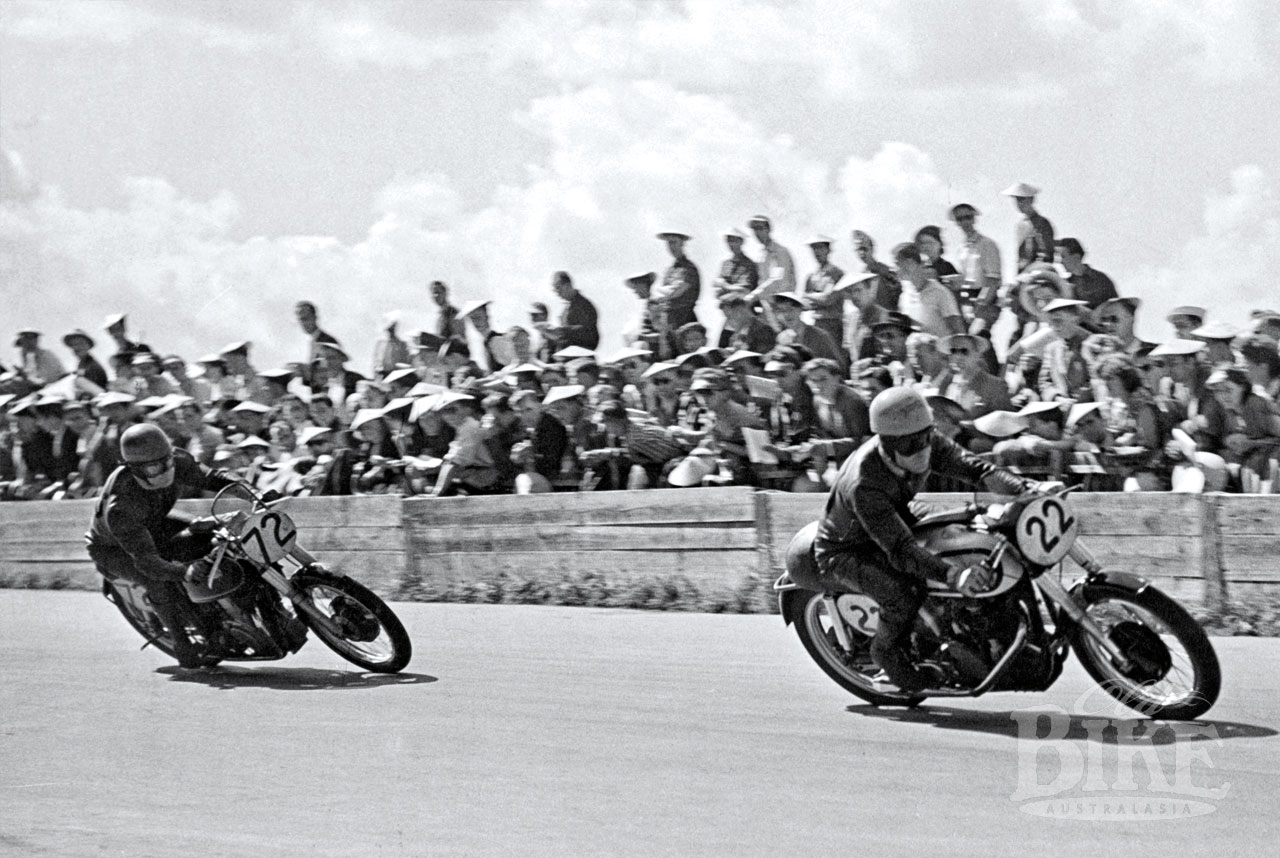

Soon after the TT, Ken rode his 500 to a win at a big meeting at Thruxton, and then took off to the Continent to begin ‘Circus’ life, travelling with British rider Bill Beevers. They largely concentrated on non-championship International meetings, but Ken did ride at the 1951 Dutch TT at Assen – a race notable for the fact that all three Norton works riders, Geoff Duke, John Lockett and Jack Brett, fell off in the 350cc event. Ken therefore finished a fine third – a GP podium in only his second World Championship event. Wins quickly followed in German and British ‘Internationals’, leading to the offer of works Nortons for the Ulster Grand Prix, which was held on the ultra-fast 16.5 mile Clady road circuit. He rewarded the confidence by taking second place in both the 350cc and 500cc races, behind team leader Duke. His season concluded with the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, where he again took second behind Duke in the 350cc race. It was then time to sail for home, with a works Norton contract for the 1952 season in his pocket, taking with him the Disney-owned Nortons, which he rode just once, at Ballarat, before they were sold to Maurie Quincey.

Once again the ‘Last-Lap” jinx hit him at the 1952 TT, retiring from fourth spot in the Junior, and having his primary chain snap in the Senior while fourth – on the seventh and final tour of both races. He lost the 350cc German Grand Prix by a wheel to Norton team mate Reg Armstrong, but that elusive Grand Prix win finally came in the Ulster Junior race – Australia’s first-ever World Championship victory. One year later the Ulster GP had moved from Clady to the 7.4 mile Dunrod circuit, and Ken brought his Norton home first in the Senior GP, defeating Geoff Duke’s works Gilera-4. Then, following the Italian Grand Prix, he sensationally quit the Norton team and announced he was off to Moto Guzzi, with a substantial pay increase that hoisted him to the mantle of Australia’s highest earning motor sportsman, and possibly the country’s top earning sportsman in any category. He actually lined up on a 250cc works Guzzi for the 1952 season-ending Spanish Grand Prix, taking second place in a race where the Italian machines swept the first five places.

Swapping Britain for Begamo

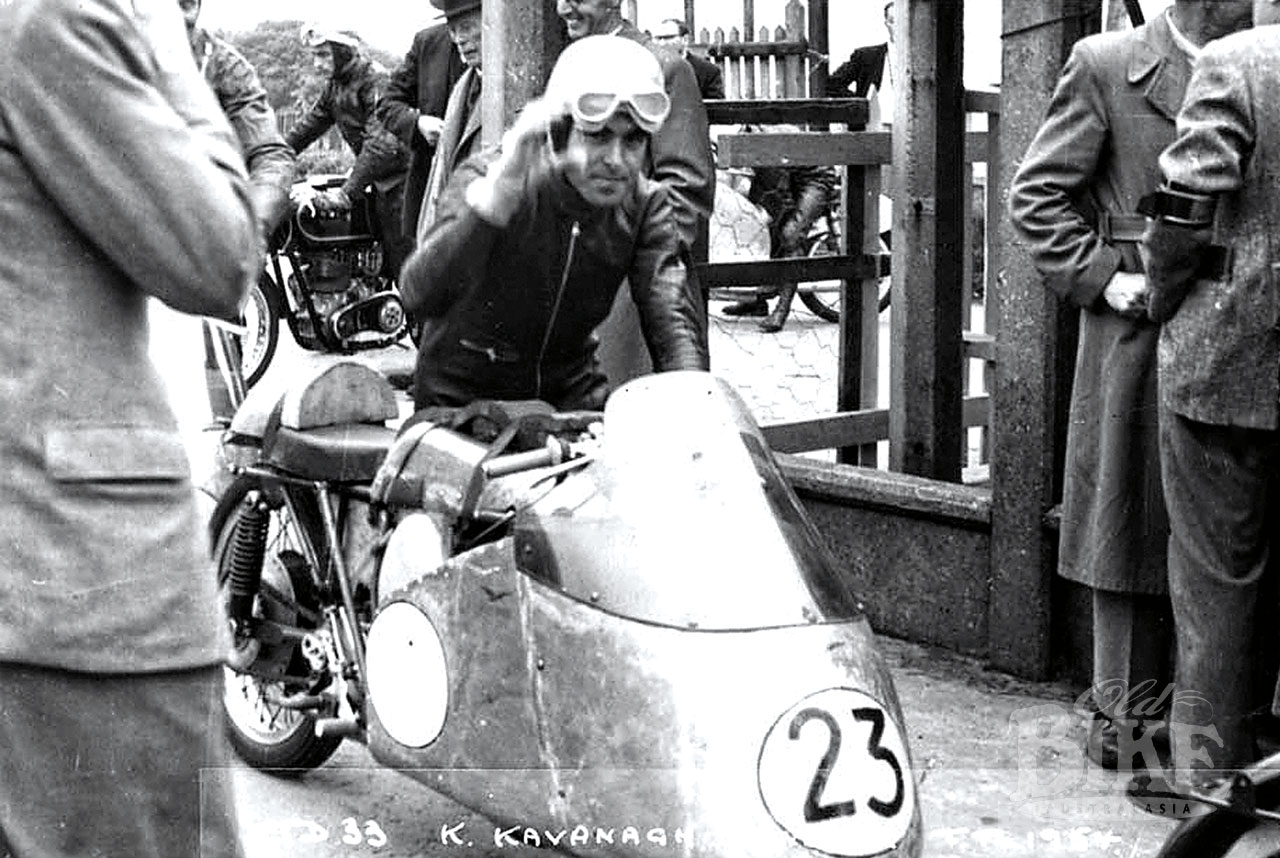

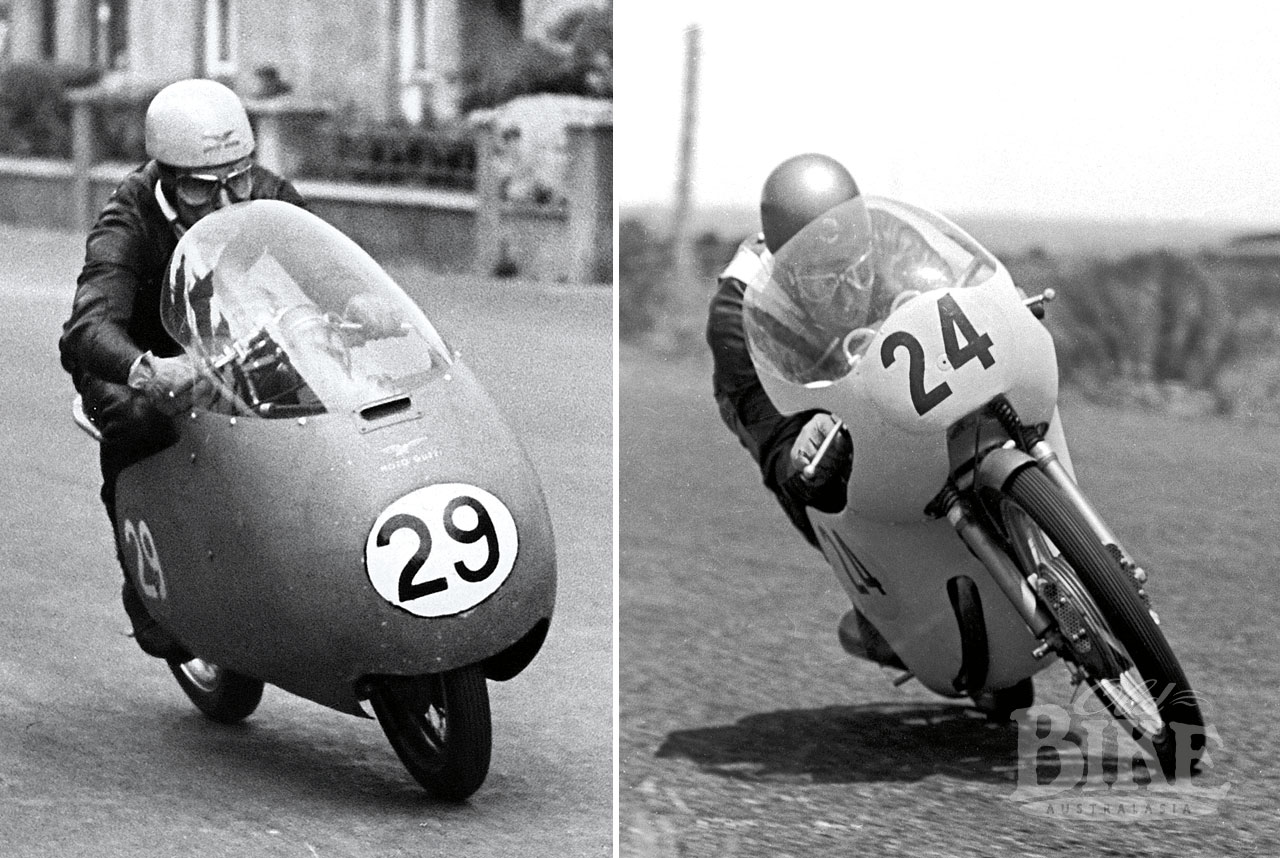

Ken settled easily into the life of a motorcycling superstar in Italy, even if his relationship with the Moto Guzzi team manager, Fergus Anderson, was a little frosty at times. Anderson openly accused Ken of ‘blowing hot and cold’ – unbeatable on a good day, and lacklustre on others. At the end of the 1955 season, Anderson quit Guzzi when his demands for absolute control over the race team were not accepted. Ken’s three-year tenure at Moto Guzzi brought three more victories, including another first for an Australian, the 1956 Junior Isle of Man TT. He was also entrusted with the development of the company’s new 500cc V8, but became increasingly exasperated with the unreliability of the 500, and at the season’s end sensationally announced that he was quitting Moto Guzzi to join John Surtees, ten years his junior, at MV Agusta.

It was a bad move. If Ken thought the management tetchy at Moto Guzzi, it was nothing compared to the tantrums and dictatorial attitude of MV’s Count Agusta, the pair forming an instant dislike for each other. Kavanagh felt the switch offered him his best chance of a World Championship, and at 33 years of age, time was running out. But the venture got off to the worst possible start when Ken arrived for the non-championship Spanish Grand Prix in April 1957, only to find the factory had not sent a motorcycle for him. After some very public remonstrations, Ken was finally given a ride on a spare 500, but soon after, at Imola, the same situation again occurred, and this time there was no ride. The hostility finally reached fever point when MV said they would not be supplying bikes for him to race at the TT, and Ken quit the team and sued for breach of contract. He was out of a ride, but by season’s end, many of the world’s top riders would be too after Gilera, Moto Guzzi and Mondial all quit GP racing.

Ken and cars

After the acrimony and disappointment of the 1957 season, which Ken largely sat out after the MV Agusta fiasco, he began to consider an alternative career as a car racer. But there was no starting at the bottom to learn the ropes; Ken went straight to Formula One. This came about because the Maserati factory, so dominant in the previous seasons and World Champions with Juan Manuel Fangio in 1957, had basically run out of money. The cost of developing their V-12 F1 engine and the V8 sports cars was one thing, but the nail in the coffin was the loss of their biggest market (Argentina) for their core business – machine tools – which was a mortal blow. With the fall of the Peron government, the new regime welched on the debts, and Maserati was forced into near bankruptcy. The racing department was closed, but a small competition workshop looked after cars for private owners. The previously dominant 250F works cars were sold, with chassis number 2526 going to 1957 World 350cc Champion Keith Campbell (who drove it at Goodwood and Aintree in England and at Syracuse in April, before perishing in a motorcycle race in France on July 13, 1958), while chassis number 2527, which had been raced in 1957 by Fangio and Harry Schell, went to Kavanagh.

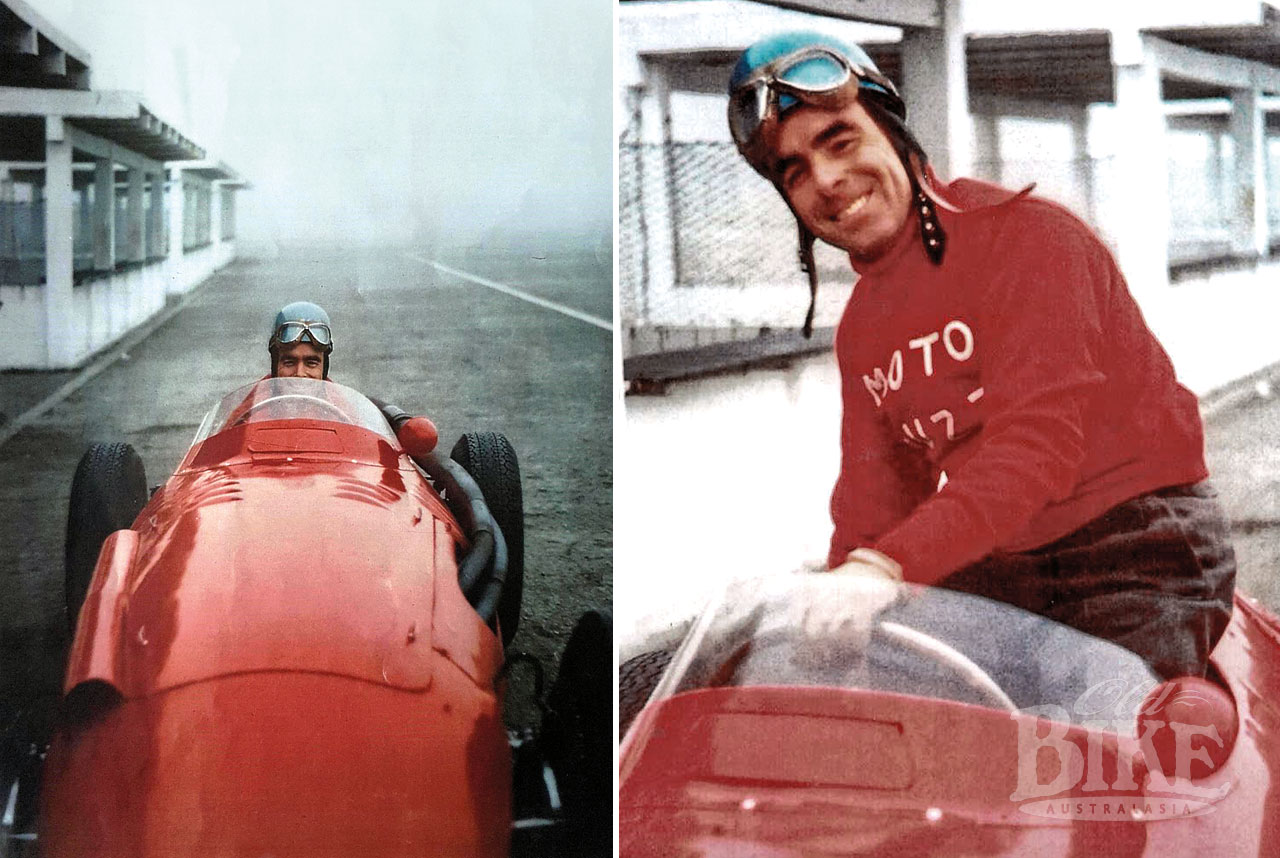

Ken tested the car at Modena on December 22, 1957, with the local newspaper reporting that he completed 20 laps in very tricky conditions including fog and light rain. He told the reporter that he was happy with the test and hoping to transit from two wheels to four ‘but I will never forget motorcycling’. Subsequently he decided to join the 1958 F1 championship for the first round in Argentina on January 19. Ken flew out on a chartered flight with some of the other F1 drivers, among them the Frenchman Jean Behra, formerly a top motorcycle racer before a successful switch to cars, who at that stage had an entry to the Grand Prix, but no car. Apparently a deal was struck whereby Behra took over Ken’s car for the Argentina Grand Prix at Buenos Aires Autodrome, while Ken was to drive it in the non-championship Buenos Aires Grand Prix two weeks later. Behra was credited with 5th place, although he was many laps adrift in a race run in heat wave conditions and won by Stirling Moss – the first GP win for the rear-engine Cooper Climax. In Ken’s driving debut, again held in stifling heat, he lasted only a few laps before retiring.

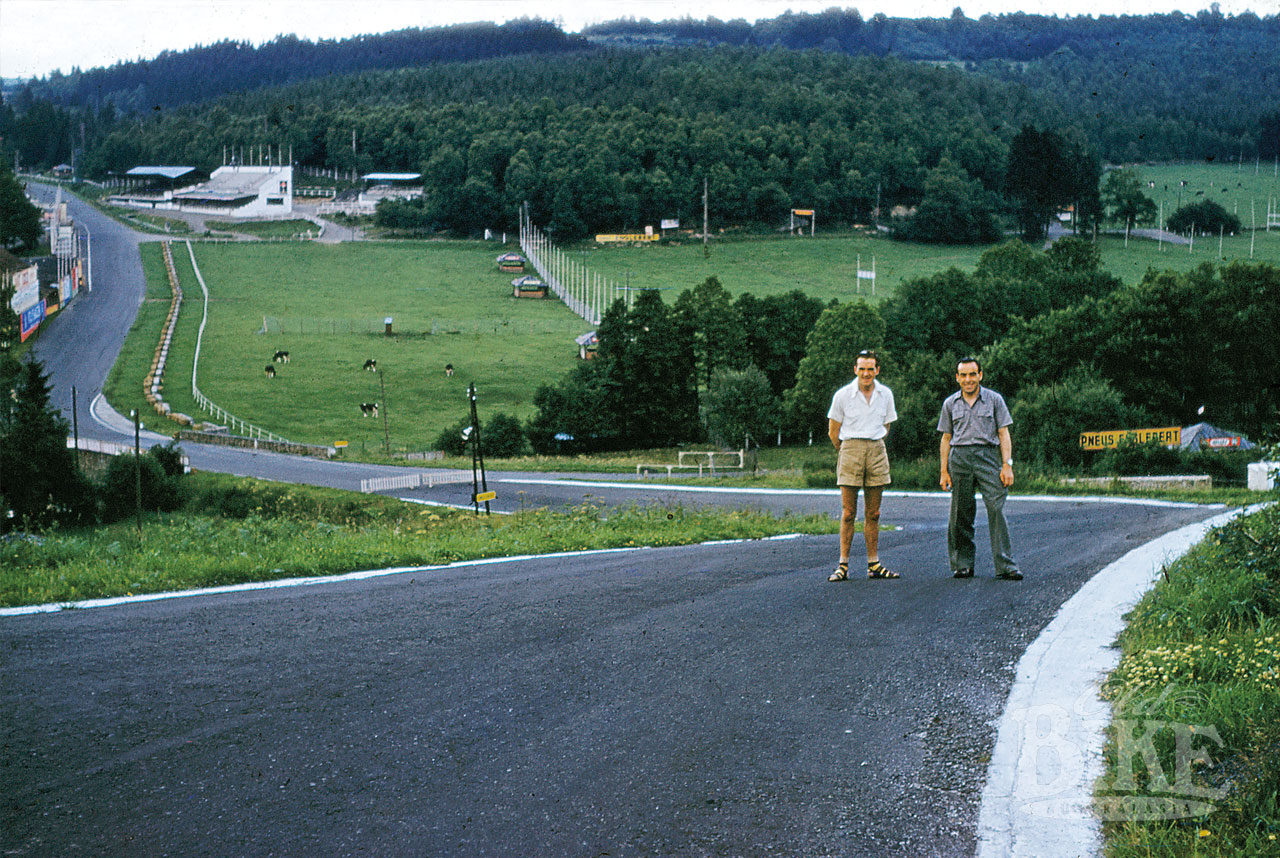

On April 13 he managed a credible 6th place at Syracuse, but failed to finish the B.A.R.C. 200 at Aintree, near Liverpool after the water pump shaft broke. Two weeks later, still in England, he could manage only 18th of 20 official finishers in the Daily Express Trophy at Silverstone after numerous problems with the car. He planned to contest the second round of the F1 championship at Monaco, but his entry was refused by the organisers. Once again, he agreed to hire out the Maserati, this time to unknown Italian Luigi Taramazzo, who never looked like qualifying for the 16-car grid. One month later, Ken was at Spa-Francorchamps for the F1 third round, the Belgian Grand Prix, but after setting a time good enough to qualify for the race, the Maserati broke a conrod on the final lap of practice, putting him out of the race. Disillusioned with the car scene and considerably out of pocket, Ken returned to bikes while attempting (unsuccessfully) to sell the Maserati. The car was returned to the Maserati factory where it was slowly rebuilt, and was loaned to the Centro-Sud team for the 1958 Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Ken still owned it in 1959 (and also had the ex-Keith Campbell car in a garage in Bergamo) and took it to Goodwood in March for the Glover Trophy. The race was run in pouring rain and Ken struggled with gearbox problems which caused him to spin the car exiting Goodwood’s famous chicane, ploughing into the pit lane wall and damaging the car seriously. The rebuild was long and costly, and it was finally sold some years later to wealthy enthusiast the Hon. Patrick Lindsay. It was later in the collection of Swiss industrialist Albert Obrist before being sold to computer industry pioneer, racing driver and author Joel Finn in the USA. It now resides in the UK owned by Peter Neumark.

Back to bikes

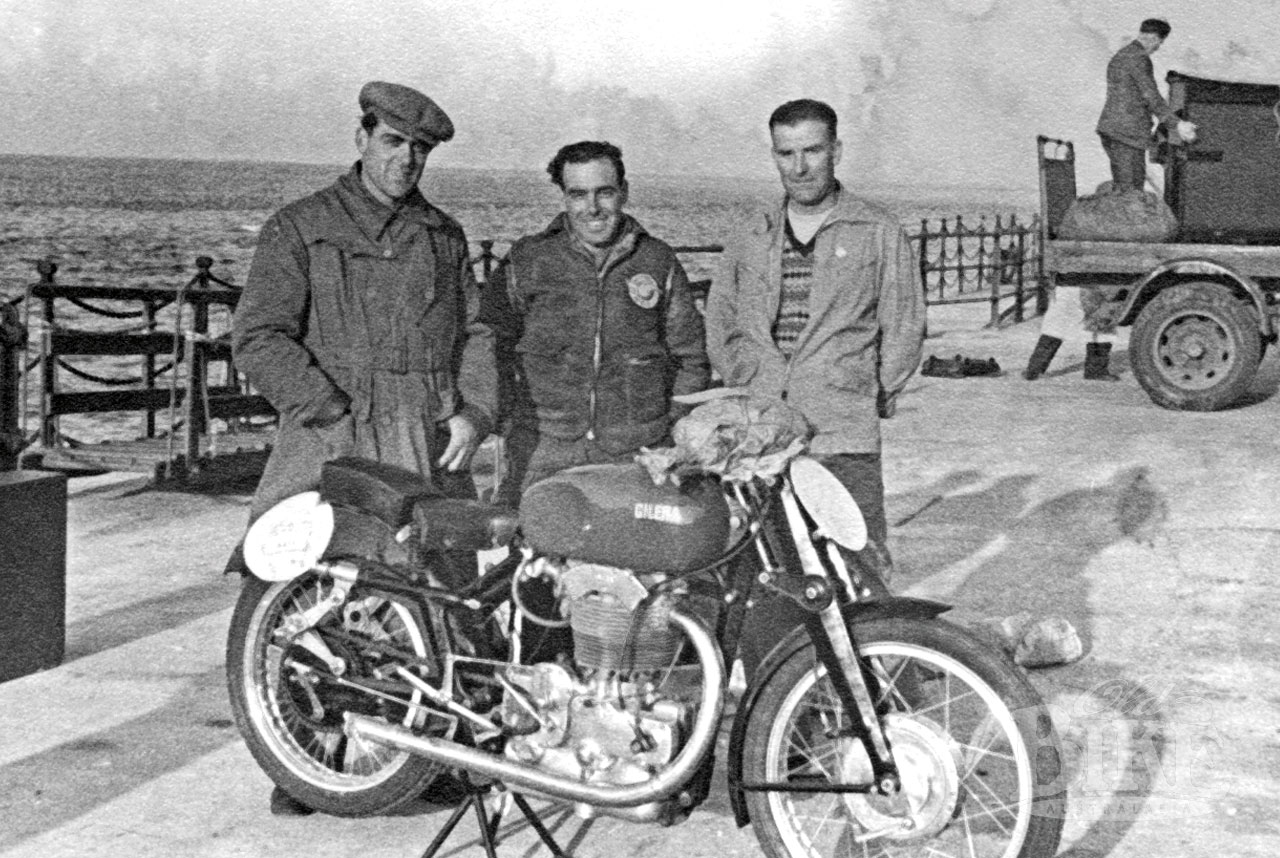

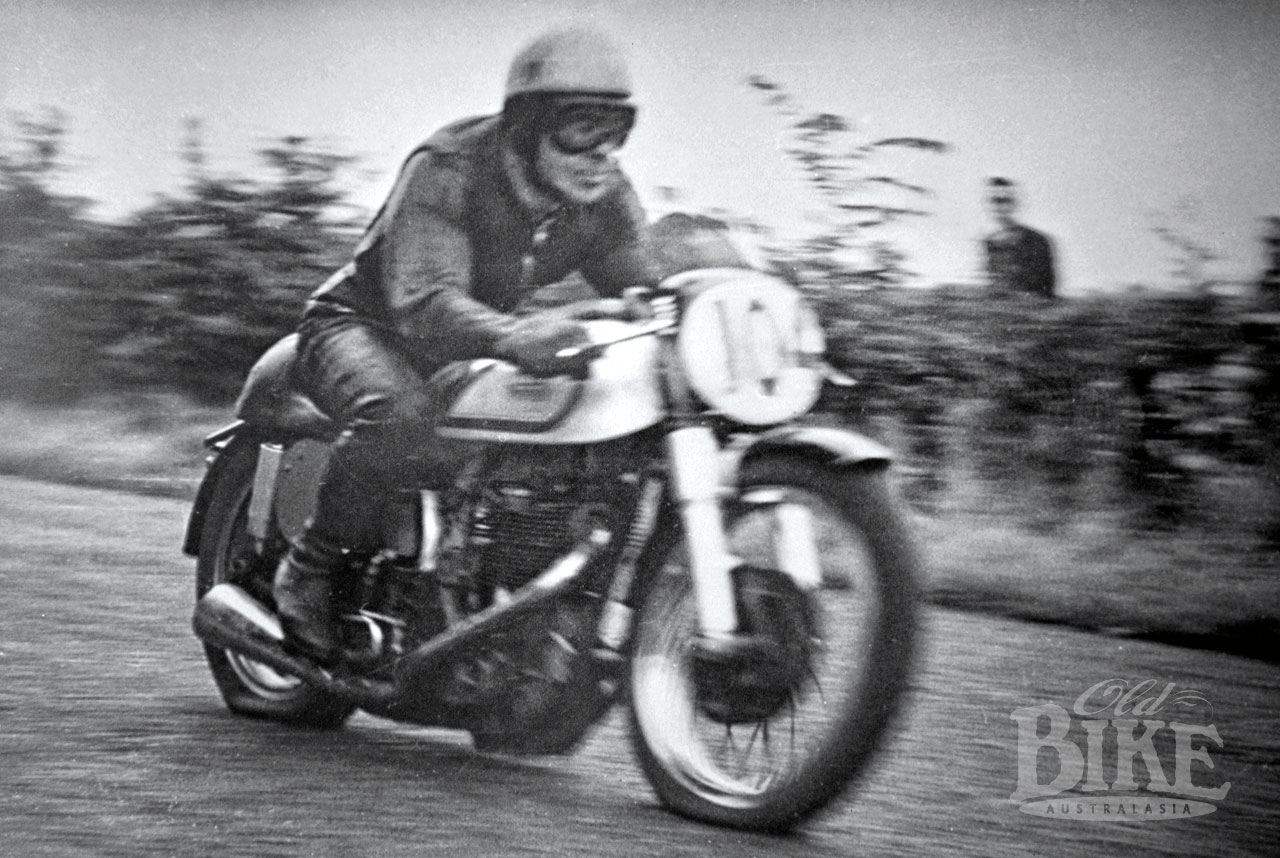

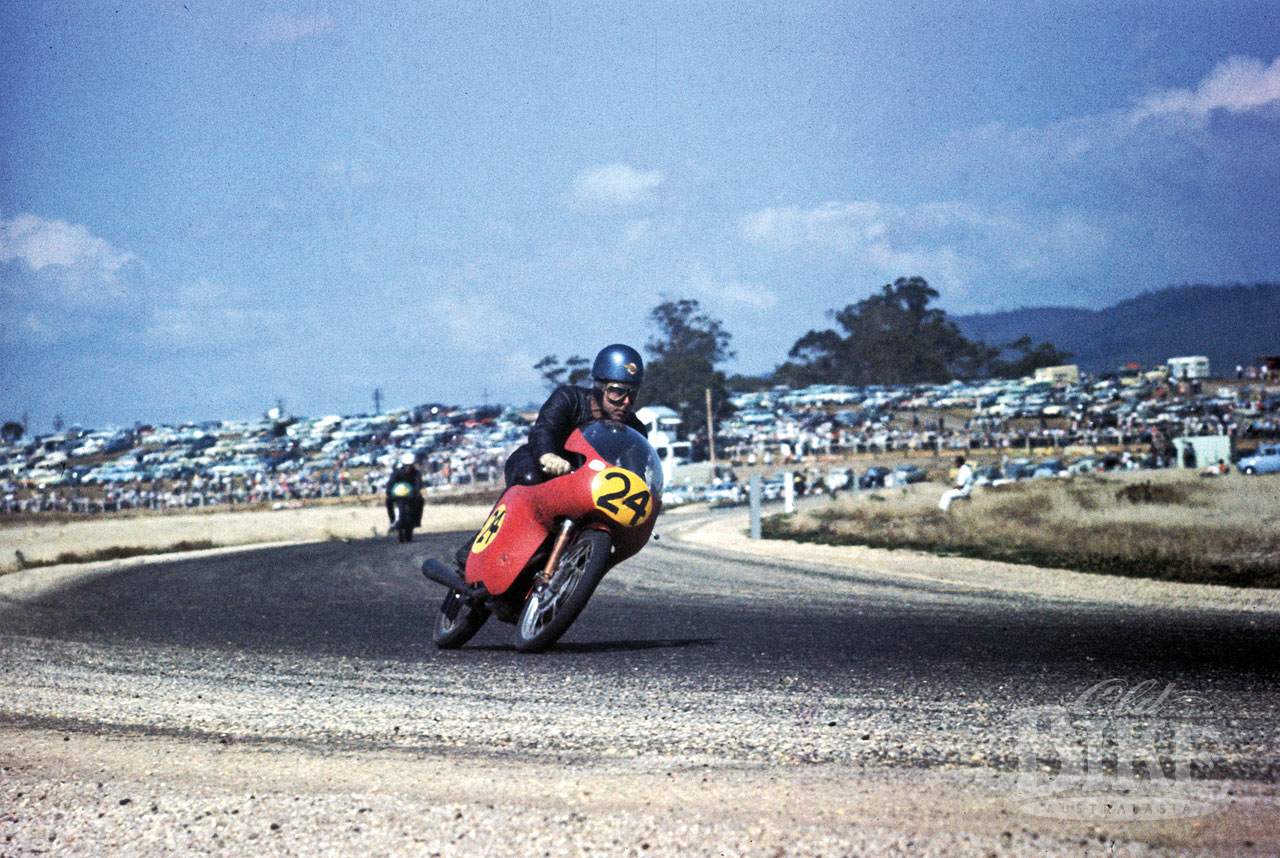

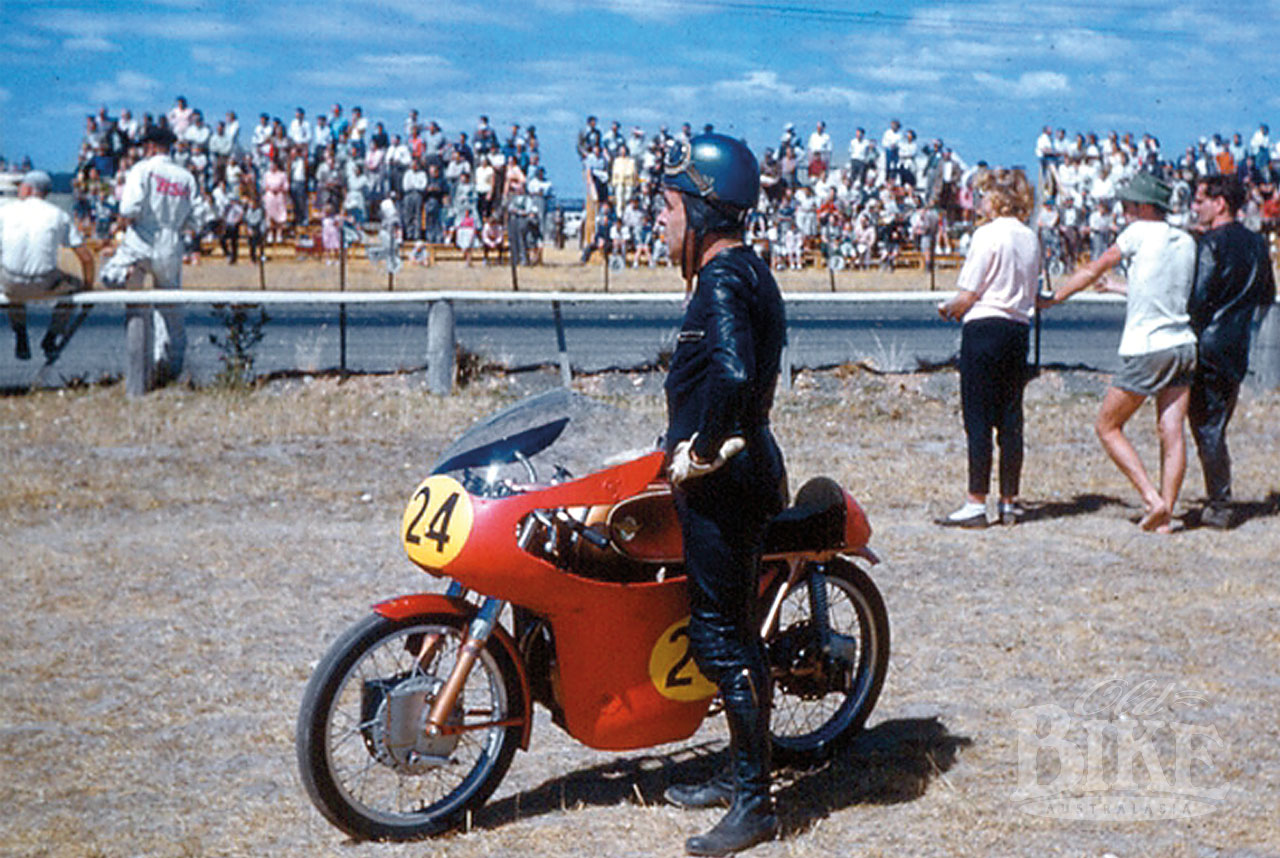

For 1959, Ken was provided with a pair of Nortons by English sponsor Cabby Cooper, and two factory-supplied 125cc Ducatis, one with a six-speed gearbox (both of which Ken owned), giving him starts in three classes. With his new wife, the Italian Countess Isabella Siotto Pintor, Ken plied the International events throughout Europe and in Scandinavia, finishing the season with a healthy bank balance. At the 1959 TT, Ken retired on the first lap of the 125cc race with a blocked fuel tank breather, but finished fourth in the one-and-only TT 500cc Formula One race – a short-lived class for factory-production racing bikes. Then, at the suggestion of Ducati, who were searching for an Australian distributor for their road motorcycles, he sailed for home with the 125 Ducati and a special 216cc model that had been built at the factory from a 175 Sport model fitted with an experimental DOHC cylinder head. Bench tested at the factory, it developed 27.5 hp, then both bikes were crated and shipped (as Kavanagh’s personal property) from Genoa, arriving in Melbourne on December 18, 1959.

The ‘216’ featured straight-cut (rather than helical) bevels, with a special one-piece fairing borrowed from Francesco Villa. Ken’s mission back home was to contest some of the ‘Summer Season’ events, and to search for a suitable distributor – his payment for this was the gift of the 216. At Phillip Island on New Year’s Day, 1960, Ken won the 125 race but retired on the 216, with what his mechanic – Harry Hinton – correctly diagnosed as carburettor flooding caused by vibration. One month later at Fishermans Bend, Ken beat Tom Phillis on Jack Walters’ 5-speed Ducati to win the 125 race, and made it a double by winning the 250 race on the 216, which was now running perfectly. The third meeting on Ken’s tour was at Longford, Tasmania, where the 125 and 250 races were combined. Ken elected to ride the 125, on which he won again, while Eric Hinton took over the 216 to win the 250 class. The following weekend was the first motorcycle meeting at the new Symmons Plains circuit and this time Hinton rode the 125 while Ken took over the 216, each winning their classes. Ken had tried to sell the Ducatis for £1000 for the pair, which must be considered a bargain, but there were no takers so they were loaded for the return trip to Genoa. Ken was amongst the front runners in the 125cc TT when the rear wheel began to collapse and he retired – his final TT appearance. The 125 was subsequently sold to Jim Redman, while Ken took the 216 to England, racing it once at Lympne, before leaving it with dealers Monty & Ward, who sold it mid-1962.

And so Ken Kavanagh finally hung up his blue helmet, and quit motorcycle racing after a career spanning 18 years. It was a complete change of pace, and not all of it successful – it took until 1964 to find a buyer for his Maserati. Eventually he set up a dry cleaning business in Bergamo which he operated for nearly 30 years.