From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 79 – first published in 2019.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Rob Lewis, Jim Scaysbrook

It was 1975 when Kawasaki stunned the Grand Prix paddock by unveiling their in-line (“Tandem”) twin cylinder 250, a motorcycle that was destined to become one of the most successful GP bikes ever, and which was joined soon by a 350cc version that was equally fond of the podium. The KR250 was not an instant success – it took until Assen in 1977 for British rider Mick Grant to score the first GP win – but from then on there was no looking back. Grant took a second GP win at Sweden later in the year, but this was just a taste of the dominance enjoyed by the Big K in the following years.

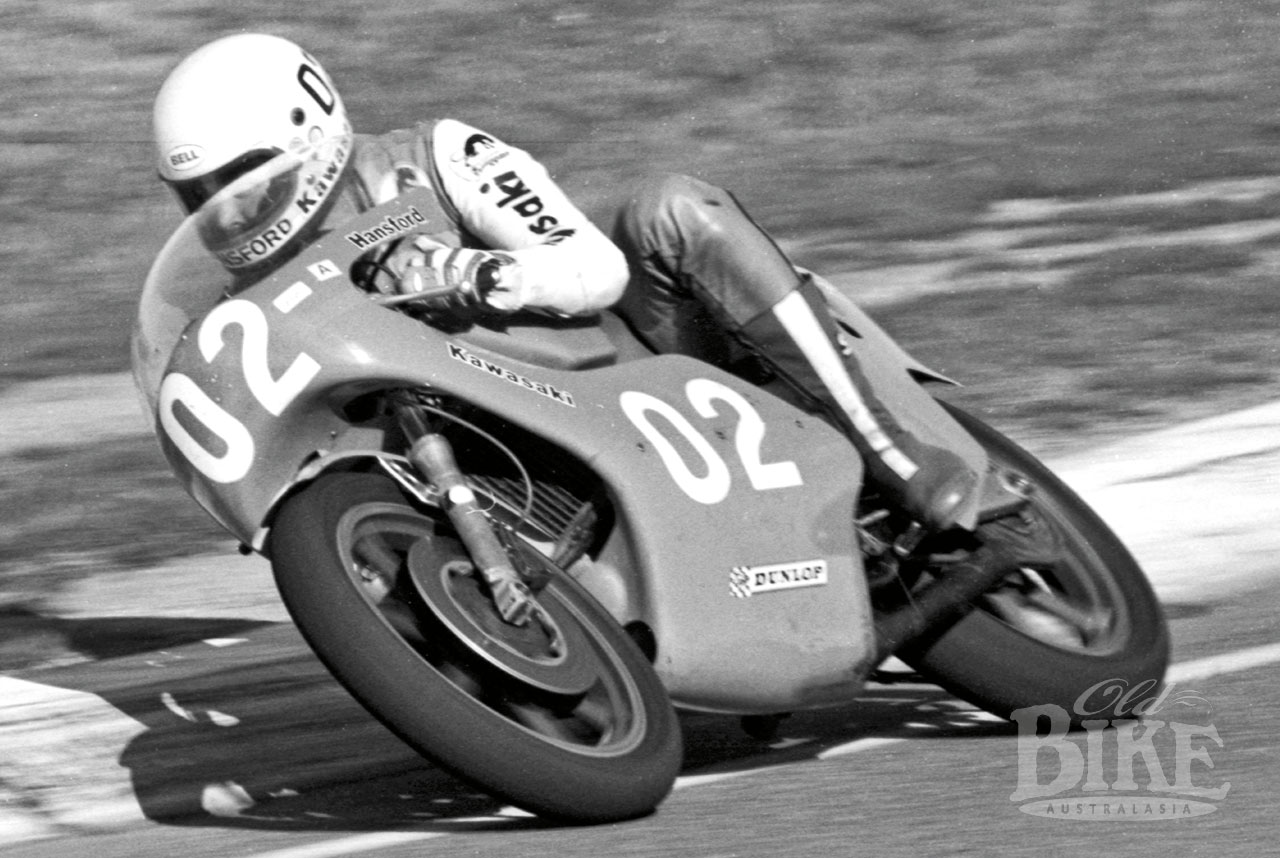

Of course, Kawasaki had ventured into the quarter litre class before, with the A1R, another disc valve racer that appeared in 1967. It was quick too, but fragile and generally no match for the Yamahas that dominated by sheer weight of numbers on grids worldwide. Unlike the A1R, which was available for sale to the general public, the KR250 was a works racer through and through, although selected machines were made available to importers in Europe and USA, as well as in Australia via Team Kawasaki Australia run by Neville Doyle with riders Gregg Hansford, Murray Sayle and Rick Perry. Prominent South Australian Kawasaki dealers Bolton’s also secured a KR250 (and later a KR350) for their sponsored rider Paul Cawthorne.

On the world stage, South African Kork Ballington battled mightily with Hansford in 1978, securing both the 250 and 350 titles, which he retained the following year. Then came German Anton Mang, who took the 250cc championship in 1980, the 250/350 double in 1981, and the 350 in 1982.

By 1984 Kawasaki had opted out of Grand Prix racing following their disastrous foray into the 500cc class with the KR500, but then pulled a surprise move by announcing a new KR250 (launched locally as the KR250A1)– not a racer, but a road-going model aimed squarely at the 250cc Production class, one of the hottest categories in the world, especially in Australasia. Its targets were the Suzuki RG250 and the Yamaha RZ250, and in the vital weight stakes, the 134kg Kawasaki sat between the two, at 131 kg and 145kg respectively. All three produced near identical power – around 24.5 kW at the rear wheel.

The Tandem twin concept was essentially a pair of 125cc singles mounted one behind the other on a common crankcase, with cranks connected by large gears. This layout perfectly suited rotary valve induction directly to the crankcases via dual carbs, producing a very slim machine with a low centre of gravity. The new KR250 roadster however, had little in common with the GP machines other than the arrangement of the cylinders. Unlike the racer, which had both pistons rising and falling together for 360º crank timing, the roadster used a 180º set up, achieved by having the right side clutch gear split, with the halves being held together by a shock-dampening system. The rear crank and cylinder sat above the gearbox keeping the overall package short and compact.

Induction was by a combination of rotary disc valves and reed valves, mounted on the right side inboard of the primary drive gears – the racing KR250 had the carbs on the left. The fuel and oil mixture entered the crankcases via Mikuni flat slide carburettors, through the reed valves and then to the combustion chambers via transfer ports. Whereas both the main rivals, Suzuki and Yamaha, opted for square bore and stroke of 54mm x 54mm, Kawasaki set theirs at an over-square 56mm x 50.6mm, producing a higher rev ceiling for a given piston speed. The cylinder head was a one-piece unit, with separate cylinders. Cooling was by water, with the pump driven from the left side of the front crankshaft. Also unusual was the exhaust system, with the front cylinder’s expansion chamber running under the engine, and the rear exiting from under the seat, surrounded by an extensive heat shield for rider and passenger comfort.

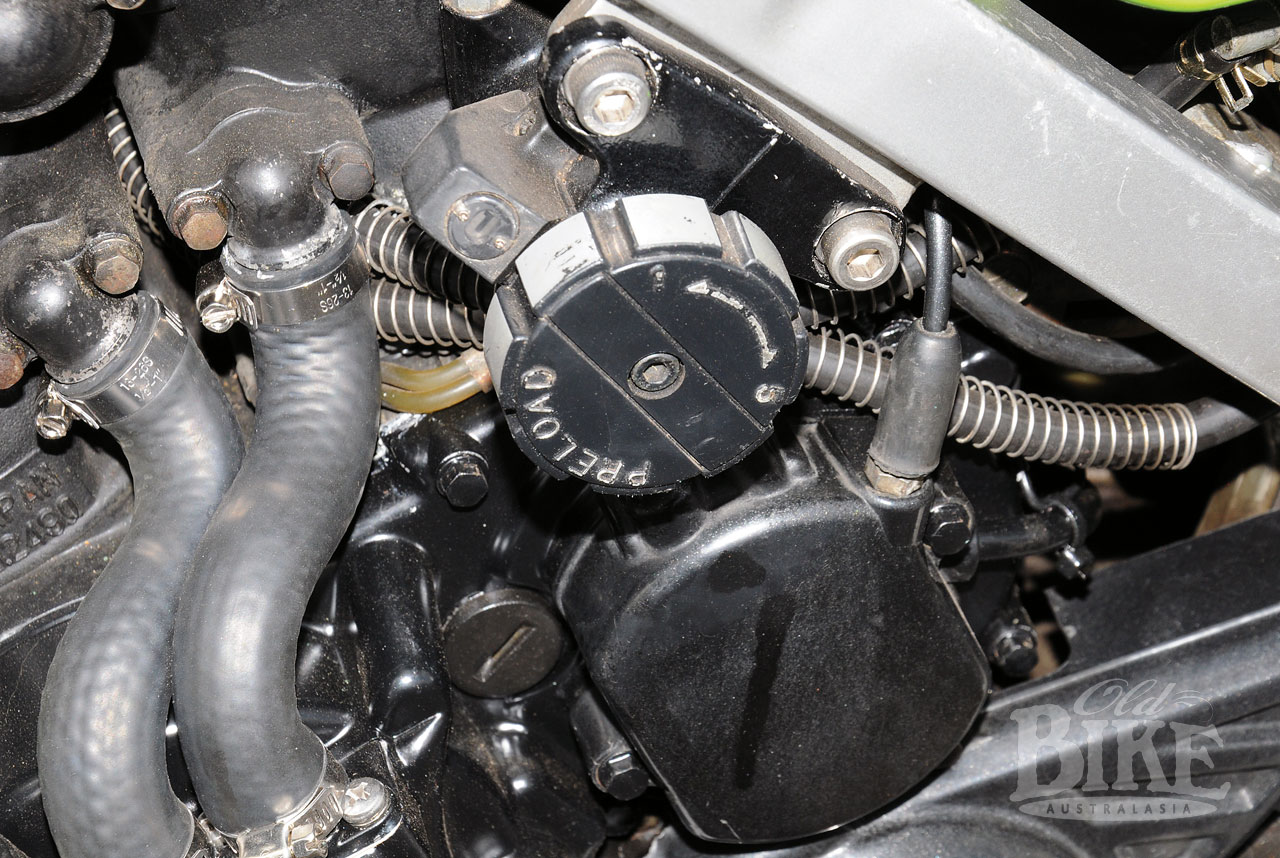

Chassis-wise, the KR250 also stood alone. Box-section steel tubing was used throughout, with the frame itself made in three pieces. The major part comprised the steering head and the widely-spaced top section of straight tubes. The lower cradle sections bolted to a pressed pivot for the swinging arm, with the rear sub-frame bolting to this and to the main frame, supporting the seat and rear mudguard. The swinging arm itself carried triangulated bracing for the bell crank which connected to the single gas-filled rear shock absorber, mounted horizontally and itself connected to the chassis under the front cylinder. The suspension unit was adjustable for spring pre-load and rebound damping, with the pre-load adjustment via a knob at knee height on the left side. The damping adjustment was done by a four-position adjuster sticking out of the belly pan on the left side. Pioneered on their successful motocross bikes, Kawasaki labelled this system ‘Unitrack’.

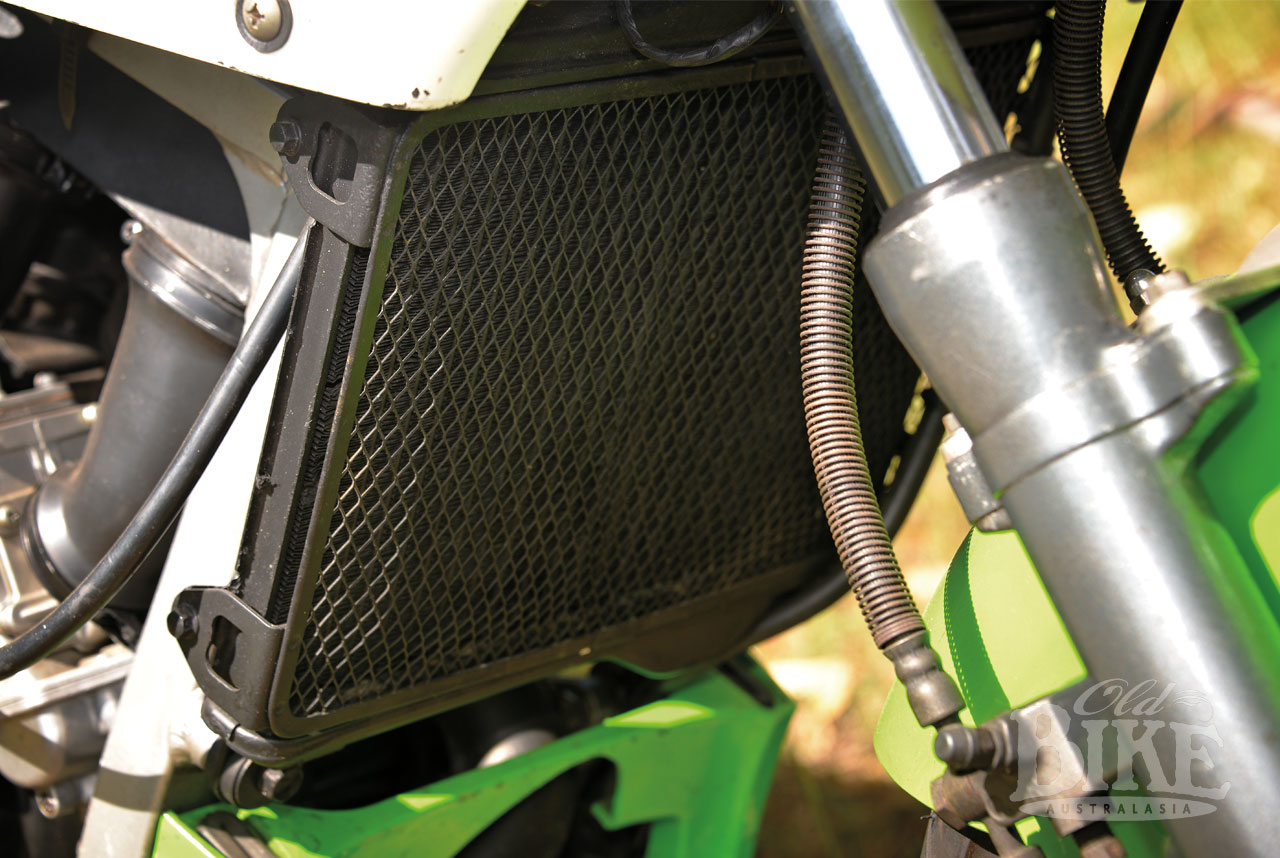

Up front sat a set of conventional forks fitted with Kawasaki’s AVDS (Auto Variable Damping System) with adjustability via air caps and a variable anti-dive. Under each leg sat a knob which could be adjusted through a range of four settings. The legs themselves were joined by a sturdy brace which also supported the front mudguard. Although in the mid-eighties the trend was towards the now-universal 17-inch front and rear wheels/tyres, the KR250 used a fat 16 incher at the front with a rear 18 inch.

The riding position was described by testers as “tightly confined”, and other less flattering words, partially due to the deeply sculptured seat which worked well on the track but allowed little room for movement out on the road. The overall riding position allowed a more upright seating than its rivals, another benefit for off-racetrack use. The 16 inch front wheel and the rake/trail combination could make for frisky handling, especially on rough roads, and the rear brake was often criticised for lack of feel, leading to lock ups on occasions.

Track attack

Clearly, the KR250 was directly aimed at the intensely competitive 250cc Production racing class, which was populated by some of the most promising emerging names in the sport, as well as a few veterans. Supplies of the new model began arriving in Australia by mid-1984 and the little green machine (entered by Team Kawasaki Australia) (which was also available in red) made its Production Racing debut at Calder Raceway on July 1st. In the hands of Rob Phillis and Scott Stephens, both more accustomed to Unlimited class machinery, the newcomer simply destroyed the opposition, running 1-2 until Stephens crashed around half distance. Phillis also claimed a new class lap record. TKA team boss Neville Doyle said the bikes had been untouched from the crate other than changing lubricants, and Phillis praised the ‘low-down grunt compared to the other bikes (Suzuki and Yamaha), and I reckon they are quicker in the top end too.” Stephens added that the KR250 was better under brakes as well. Doyle said, “It’s got fairly usable power from 6,000 rpm and it goes right through to 10,500. There are no sudden jumps in the powerband or anything like that. It makes it more rideable than the other 250s.” There was so much muttering among the vanquished that officials impounded the top ten finishers at Calder for a mandatory strip-down to check all was as it should be. The result was that the two KRs passed with clean sheets, while four of the opposition did not. Slightly miffed, Doyle said that the KR250 had proved its point and that TKA had no further plans to enter the 250s in Production races. Among the opposition, several were already on their way to the local Kawasaki dealer to place an order.

For the next two seasons, the KR250 held its own in the class, notably in the hands of former Suzuki rider Ian ‘Buster’ Saunders, who scored many wins. Probably the highest profile event for the class was the annual Bathurst meeting, but in 1985 Saunders could only make it to third after a bad start before the KR250 went onto one cylinder in a race dominated by RZ250 Yamahas, and where the first ten finishers all substantially bettered the existing lap record. Winner Rusty Howard’s RZ250 Yamaha clocked 196km/h down Conrod Straight, compared to Saunders’ 180km/h. It was the same story in 1986, when the marque trio became a quartet with the arrival of the Honda NS250. Again, the lap record was pummelled and in a five-way sprint to the line, Saunders’ KR250 was out-dragged and he finished fifth.

That was about it for the Tandem Twin as far as production Racing went, with the new TZR250 Yamahas engulfing the class for the next two years. With the model clearly outclassed, Kawasaki went back to the drawing board and scrapped the Tandem Twin concept in favour of a conventional parallel twin (although still with the KR’s 56 x 506 bore and stroke), the KR-1 and later KR-1S. Launched in 1989, the KR-1 took on, and briefly defeated, Suzuki’s all-conquering RGV250, which itself launched the careers of so many top racers, including Mat Mladin and Troy Corser. In its ultimate form, the KR-1S was good for 55 bhp, but production ended in 1992.

Today, the original KR250 is a very collectable motorcycle, provided you can find one that has not been ridden to destruction. With its confined (cramped?) riding position it is not a machine for the larger rider, but the torque and wide powerband make it a more forgiving package for everyday riding than its traditional rivals.

Thanks to Alan Phillips for the opportunity to photograph his 1984 KR250, which was imported to Australia through Old Gold Motorcycles at Londonderry NSW. (www.oldgoldmotorcycles.com.au)

Specifications: 1984 Kawasaki KR250.

Engine: Tandem twin two stroke with rotary disc valves and reed valves. Water cooled with lubrication by pump-fed automatic injection.

Bore x stroke: 56mm x 50.6mm

Capacity: 249cc

Compression ratio: 7.0:1

Carburation: 2 x Keihin PWK 28

Ignition: Solid State Battery and coil

Starting: Kick

Power: 49 bhp at 10,000 rpm

Torque: 36.3 Nm @ 8m000

Transmission: 6 speed

Suspension: Front: air assisted forks 3 way adjustable AVDS anti dive. 120mm travel

Rear: Single shock with adjustable damping and 5 way pre load. 100mm travel.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 260mm discs with single piston floating calipers.

Rear: 1 x 240 mm disc with dual piston fixed caliper.

Wheels: Front: 100/90 VR16 Rear 11/80 VR18

Steering: Rake 27º trail 84mm

Dry Weight: 134kg

Fuel capacity; 18 litres

Top speed: 180 km./h

Price: (NSW 1984) $2,899.00