From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 99 – first published in 2022.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: OBA archives.

Many regarded the 750cc H2 as merely an abrogation of the hair-raising H1 500, but this was a whole new motorcycle, and much the better for it. Today, the H2 is rightly regarded as a modern classic.

Kawasaki always did things slightly differently to its Japanese motorcycle manufacturing counterparts. While Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha were making little bikes, Kawasaki went the other way with the BSA-inspired 650cc W1 twin. The company’s involvement in bikes stretches back to 1948 when it began supplying component parts to other companies as well as designing its own motorcycle engine. Under the Meihatsu brand, the company released 150 cc and 250 cc four stroke engines in 1953, and produced its own complete motorcycle – a 125 based on the ubiquitous DKW/BSA Bantam concept – in 1955.

But it was the Kawasaki takeover of the long-established Meguro brand in 1964 that launched it into the forefront of the Japanese market. Meguro’s T1, a 500 twin, became the W1 650 under Kawasaki’s stewardship, and sold reasonably well in the key US market. The smaller models also gained a foothold in the US, to the point that Kawasaki had a complete range stretching from 60cc through to the 250 cc and 350 cc twin (A1 and A7) and to the big four stroke twin, but the company’s design staff hankered for a real breakthrough that would stamp Kawasaki as a real innovator.

The result was the Mach III, or H1, which was conceived in great secrecy and code-named Blue Streak – a triple cylinder 500 that was primarily designed as a straight-line rocketship. Two stroke triples were not unique of course; back in the ‘thirties Scott had produced 750 cc and 1000 cc water-cooled two stroke triples, and DKW had triples of its own even before that. Kawasaki keenly observed DKW’s development of the concept, including the loop-scavenging process that was copied universally by the Japanese factories. The first H1 sketches were made in 1964, and two years later the project was in full swing, working towards a launch in 1968.

A triple triumph

Initially, the thinking swung behind an up-scaled version of the disc-valve 350cc A7 twin, but in parallel to this, a second design team was working on a 500cc air-cooled triple, with the aim of producing 60 reliable horsepower. Cooling was the critical issue, and Kawasaki looked at all sorts of options, including a vee concept with the centre cylinder vertical and the outside pair canted forwards. After extensive testing with the vee and a more conventional in-line three, the latter was chosen as the preferred route. Like the A1 and A7 twins, the new triple was to be fitted with capacitor discharge (CDI) ignition which had proved to be a very efficient way to minimise unburned gas in the combustion chamber and hence, anticipate forthcoming emission regulations. However initial deliveries to Europe were fitted with conventional coil and points, as the CDI apparently interfered with television reception.

When the H1 appeared in 1968, two things were immediately obvious. It was incredibly fast in a straight line, and in anything other than a straight line, handling was unpredictable to the point of being frightening. There were many reasons for this, not least that the H1 chassis was essentially the same as the 250 A1, the swinging arm area flexed and the rear shocks had inadequate dampening, and the steering head angle was all wrong. Nevertheless, the Americans, for whom the H1 had been primarily aimed, took to it quite strongly, although they did insist on calling it the Mach III as H1 was deemed too boring. Sub-13 second standing quarters headlined the ads, which dominated the big-selling US magazines of the time. The new 500 was quite a good-looker, its raked lines and distinctive white-with-blue colour scheme setting it apart from all others. Praise from the magazines’ road testers was lavish and constant, with plaudits for the ‘space age’ capacitor discharge ignition, metered oil injection to the main bearings, and most of all, the price. At $999 the Mach III undercut the new Honda CB750 by $400. Perhaps in deference to the volume of Kawasaki’s advertising spend, little was said about the handling.

Fast forward

The H1/Mach III soldiered on through several models, the H1B finally receiving a disc front brake to bring it into line with the competition. But the big news came in 1971 with the almost simultaneous release of the 350cc Mach II and 750cc Mach IV, giving Kawasaki a three-strong (or Tri Stars in the US advertising parlance) line up for its triples.

The H2/Mach IV was not just a bigger engine, albeit one that poked out an impressive 74hp at 6,800 rpm; the chassis, although clearly based on the H1, differed in several areas, importantly in a longer (1,410 mm) wheelbase. Extra attention to ground clearance saw the exhaust pipes tucked in and the mufflers raised, but most testers still reported that it was the positioning of the engine unit that was the main problem with the persistently devious handling. The high and rearward setting for the engine still made the front end too light, producing tank slappers in a straight line and speed wobbles on bends. The Italian press dubbed the bike “Bara Volante” – The Flying Coffin – while the Americans preferred Widow Maker.

Even Kawasaki itself was not coy about the H2’s personality. The factory brochure read, “The Kawasaki 750 Mach IV has only one purpose in life; to give you the most exciting and exhilarating performance. It’s so quick it demands the razor-sharp reactions of an experienced rider. It’s a machine you must take seriously.’ Amen. However to be fair, the H2 was a marked improvement on the original H1, with considerably more torque and a lower rev ceiling that helped keep the engine cool. Maximum torque on the 750 was developed at just 6,500 rpm, so it could be ridden easily in traffic without trying to break loose. Fuel consumption wasn’t a strong point – around 22 mpg was the best that could be hoped for.

On top Down Under

While deliveries to Europe were slow in order to concentrate on the US market, the H2 made it to Australia in late 1971, with a retail price of $1,399.00. The H1B sold alongside it at $1,135, while the new 350cc triple S2 was $950. Mitsubishi CDI was standard – the earlier TV reception problems seemingly overcome. As on the H1, the gearbox was still a five-speeder, and still with neutral below first gear, which was a definite drawback for racing, especially with the fairly high (2.17) first gear.

To guard against getting a crankcase full of fuel when the bike was left standing, the fuel tap was vacuum operated, having a manual priming position and a second position where the tap was sucked open by engine impulses. Other nice touches include a small oil tank under the left side cover with a tube leading to the rear chain. This is a manually-operated tap and relies on the rider to perform the task when necessary. There was extra storage space inside the rear seat compartment where the tool kit was located, and unlike the US models with their bobcat styling, the rear tyre was encased in a full length chrome steel mudguard. In fact, steel was used for both guards, the side covers, headlight shell and rear chain guard.

As larrikin as the H2 was, something had to be done about its manners, and following the slightly revised H2A of 1973, the H2B sported a longer swinging arm and revised geometry at the steering head. Along with the chassis revisions came a marginally detuned engine, and revised mufflers – constantly trying to stay ahead of the challenging US emission laws, with 30 mm carburettors and a consequent reduction in power to 71 hp.

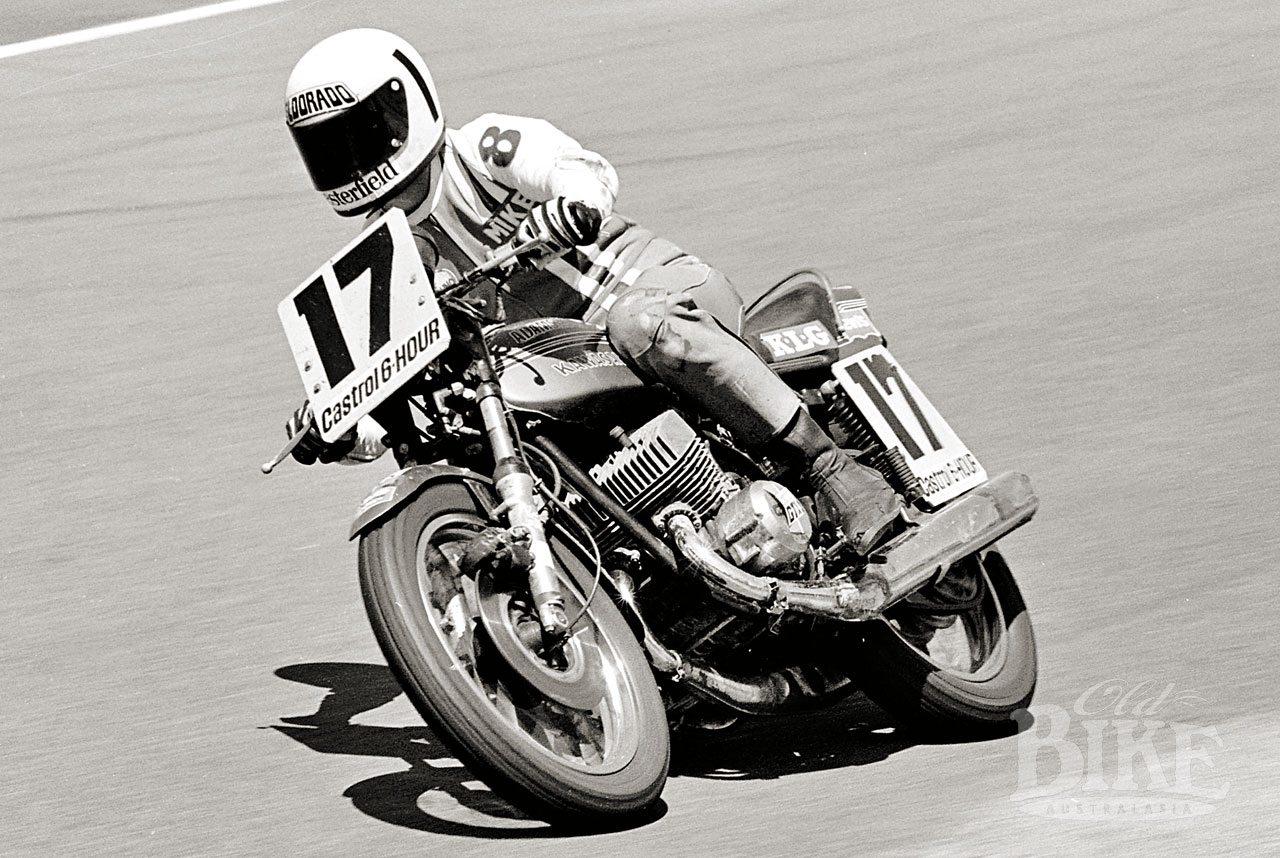

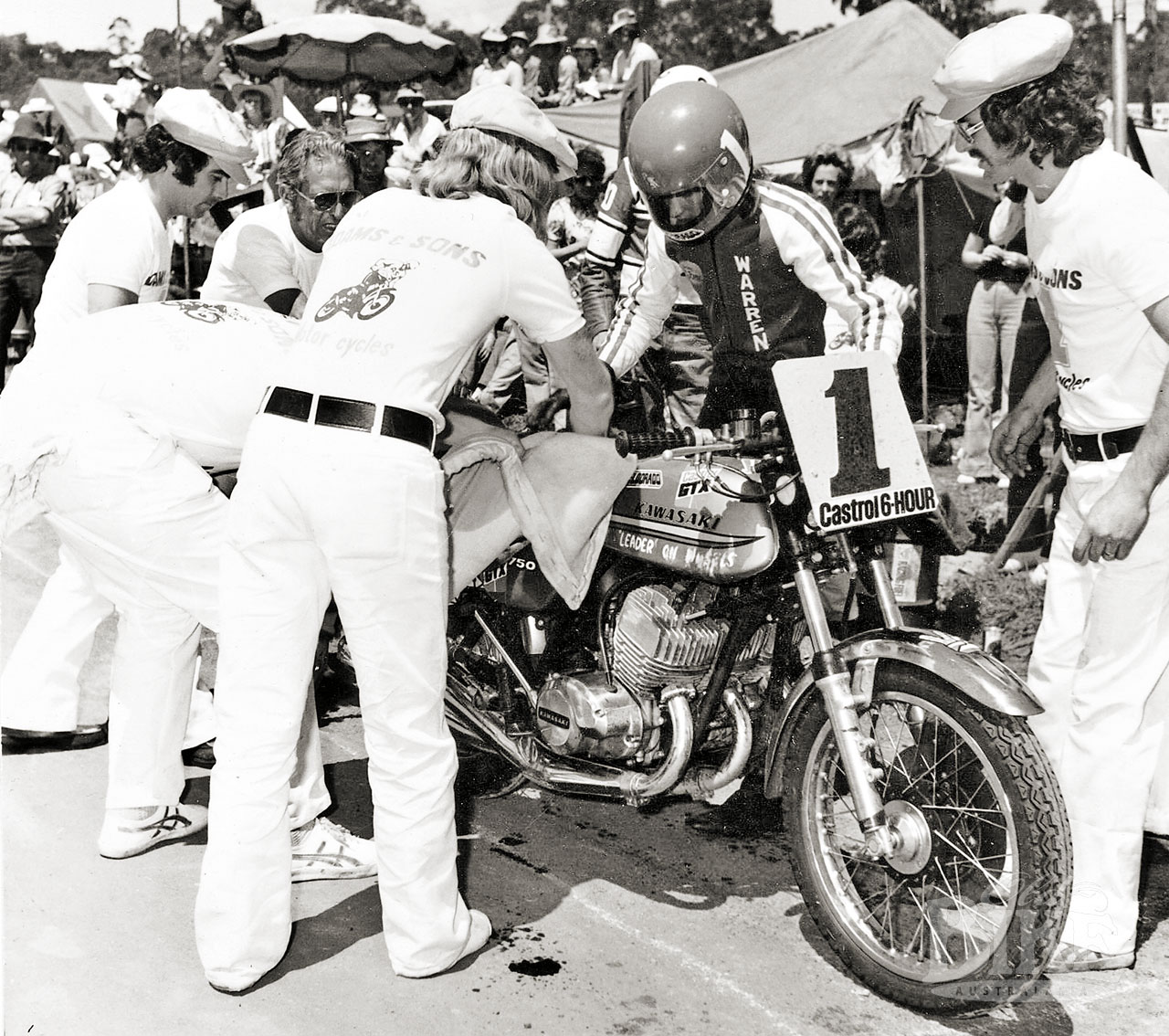

At the time of the H2’s introduction, the Castrol Six Hour Race was the ultimate test of production motorcycles. Four examples were entered for the race at Amaroo Park on October 15, 1972, for Gregg Hansford/Rob Hinton, Mike Steele/Dave Burgess, Geoff Lucas/Marcus Caux, and Owen Ellis/Peter Jones. Practice sessions showed the bikes to be extremely fast, and the clockwise circuit with predominantly right-hand corners suited the bike’s ground clearance, which was at its worse on left handers. Two of the three however, barely made it to the one-hour mark before needing fuel, while the H2 entered by Adams & Sons for Steele and Burgess stayed out for an extra 10 minutes, due to the fact that chilled fuel had been used for the race start, allowing an extra litre to be crammed in. By half distance, Steele had the H2 back in the lead and had pulled out the best part of a lap’s advantage over the Suzuki T350 ridden by Joe Eastmure. After setting the fastest lap of the race, Hansford retired his H2 with the front brake pads down to the metal.

The race reached a dramatic conclusion amid total confusion as to who was actually leading the race. Steele had been shadowing Eastmure, thinking he had most of a lap’s advantage, but his team wasn’t too sure and hung out the “Go” sign with just five minutes left. Lunging around the outside of Eastmure through the tricky Brabham Loop, Steele hit a patch of oil from a fallen Honda and dropped the model. Quickly scampering to his feet he was back aboard and coaxing the battered Kawasaki around the final half lap to the finish line. Eastmure and the little 315cc Suzuki were acclaimed the winners, but thrown out at post-race scrutineering after ‘irregularities’ that included some special work on the piston skirts and the removal of the horn. And so the H2 triumphed in its race debut, albeit in highly controversial circumstances.

The following year Warren Willing and Kiwi John Boote staged a monumental battle on their H2 against the Kawasaki Z1 ridden solo by Ken Blake, the four stroke taking victory due to less fuel stops than the quicker two stroke. The H2 really achieved infamy in the 1974 Six Hour, when the Willing/Hansford bike was found to have had the gears undercut and was disqualified; both riders receiving licence disqualifications.

By 1975, time had run out for the Kawasaki triples. Kawasaki had a bullet performer in the Z1 on its hands, and increasingly tough US laws meant that big two strokes would find it virtually impossible to comply. A total of 47,611 H2s were manufactured over the four-year lifespan of the model.

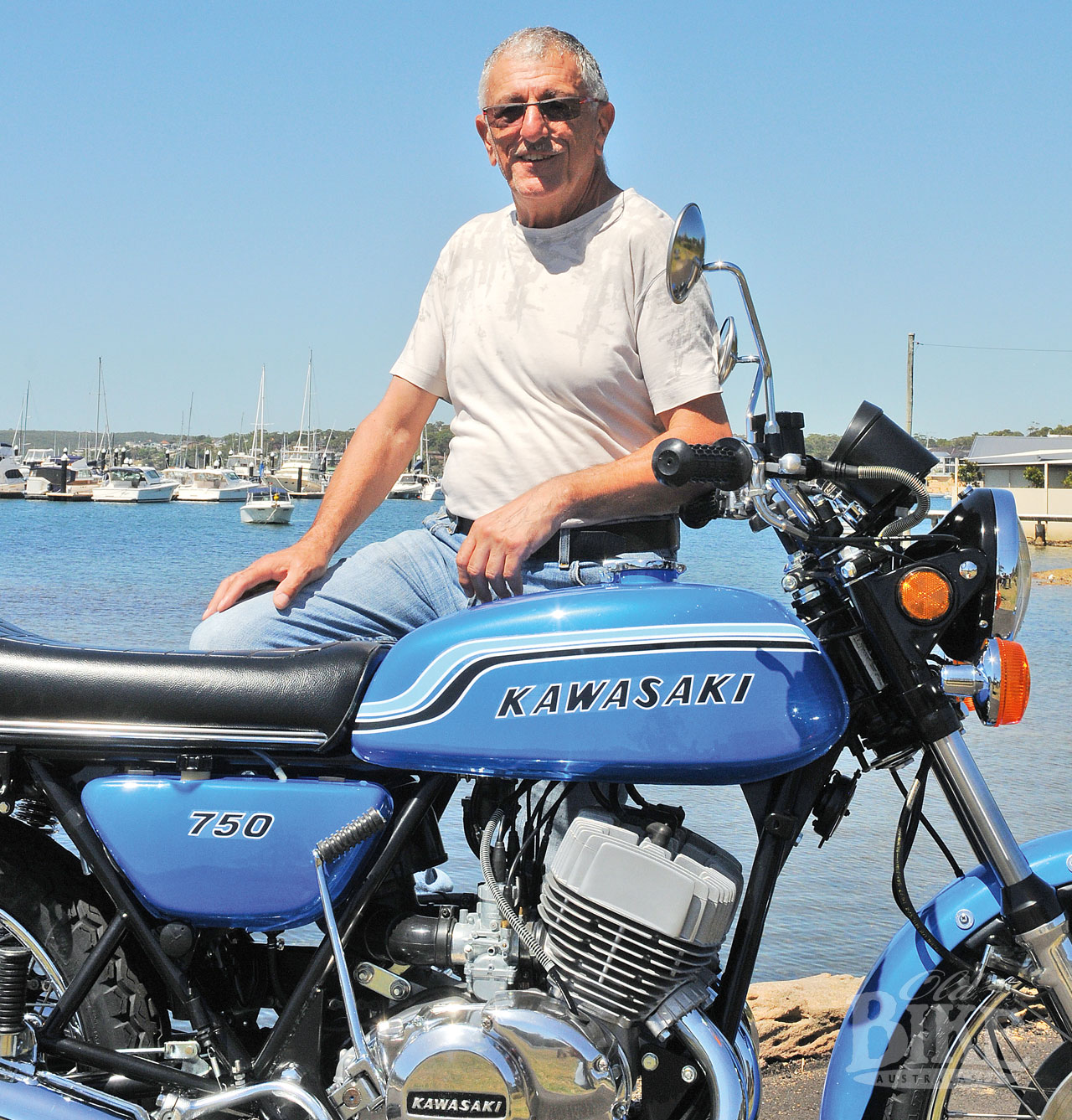

A local H2

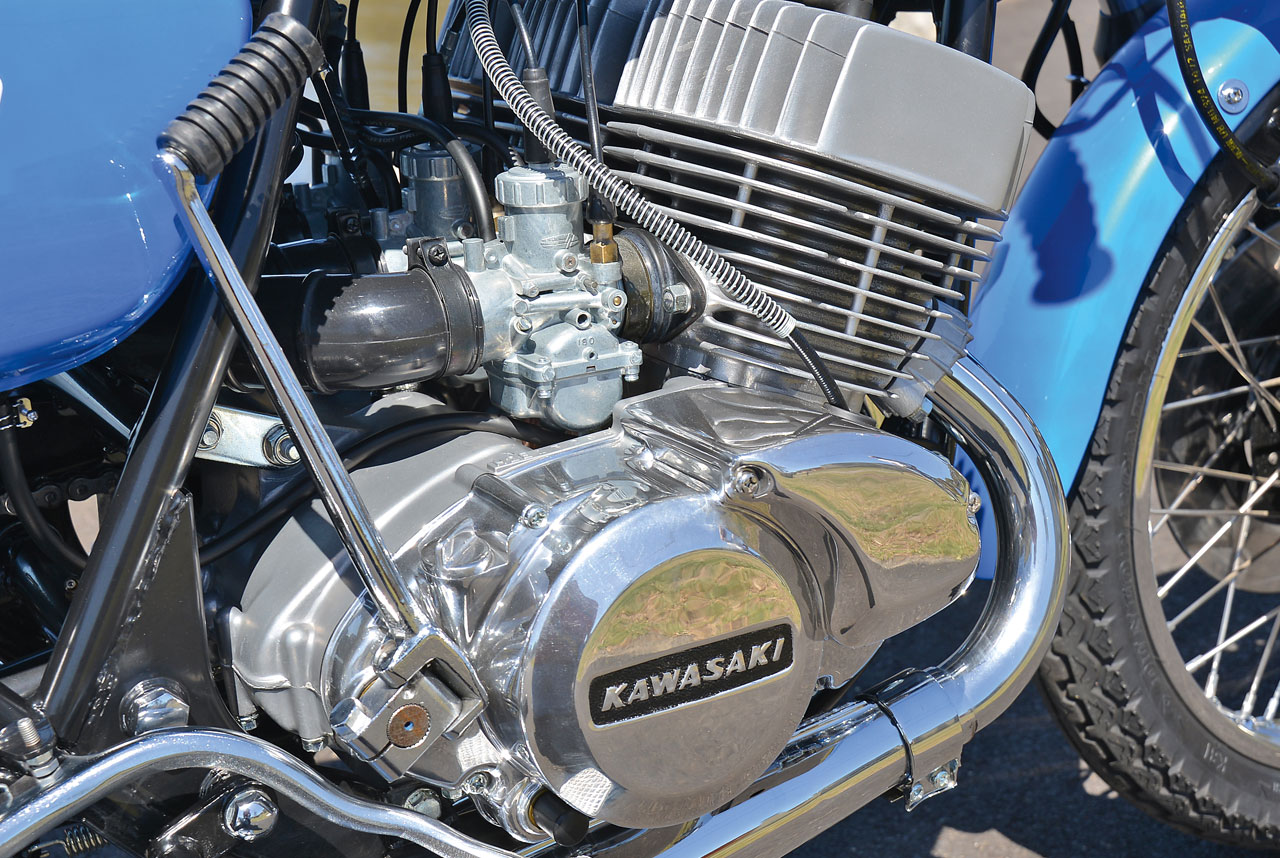

Steve Ashkenazi has been around high performance two strokes for most of his life; as a rider, as a dealer, and as a tuner to some of the top names in the sport. In retirement, he has the time to surround himself with restoration projects representing the bikes he grew up with, and one of the examples of his excellent work is this 1972 Mach IV – we use the US description because it is a US import, as evidenced by the stumpy rear end that dispenses with the Oz-market long rear mudguard.

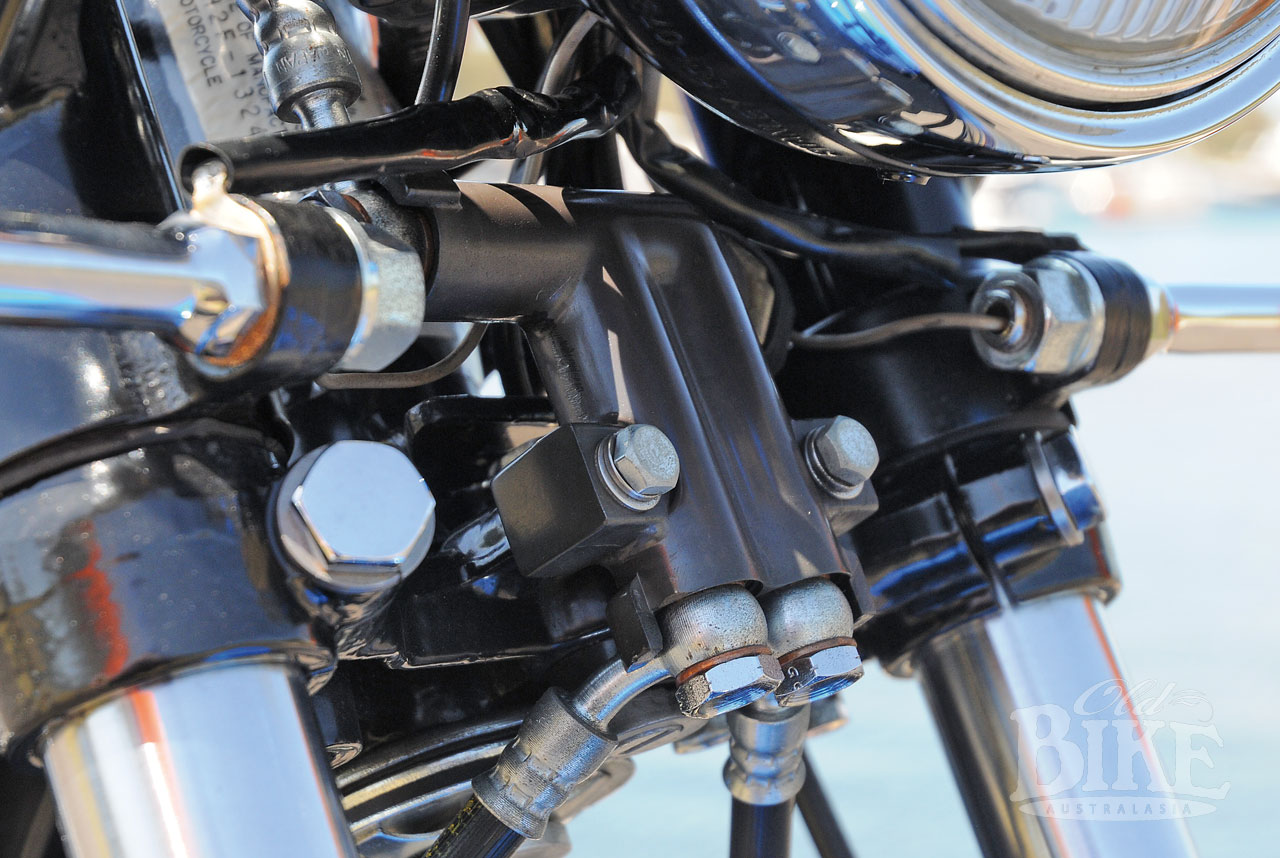

Steve’s H2 is a 1972 model, which was available in the blue colour as well as gold. The following H2B model used a chromed front mudguard instead of painted.Steve is a keen rider and for this reason he has fitted twin front disc brakes. “The H2 is a quick bike, and it needs all the stopping power it can get, so I have fitted the optional twin disc set up, supplied by Z1 Enterprises in USA. There was a factory twin disc kit available for the H2, but it was very expensive so few people fitted it. However the discs are dimensionally identical to the Z1 so the US kit is quite reasonably priced and comes with the hoses, splitter and master cylinder.”

He has also fitted locally made Ikon rear shock absorbers, which offer a far more comfortable ride than the originals. “The Ikons have four positions for rebound damping, which is a great improvement,” says Steve. “The original shocks only have the three-way spring preload and weren’t much good.” It takes a sharp eye to pick the Ikons from the originals, so the change is cosmetically compatible as well as practical.

“When I got the H2 it was fairly original but the crank seals were on the way out so I decided to fully restore it rather than just overhaul the engine. It was on standard bores, but I found a set of first oversized pistons and rings in New Zealand. The frame is powder coated and I rebuilt the wheels with the original rims re-chromed and a set of stainless spokes from Brian Morgan in WA, but otherwise the bike is completely standard. H2 parts are hard to come by – unlike Z1s where almost everything is available.” You don’t see many restored H2s about, and that makes Steve’s example stand out in a crowd. And this is no static exhibit – it is often ridden in rallies and ridden the way the model was intended, with a strong right hand. Is there any other way?

Footnote: Due to changing circumstances, Steve decided to sell this H2 through Shannons Auctions in Sydney in 2017. It realised a quite staggering $33,500 which reflects the comprehensive and authentic rebuild to which it was subjected, as well as the realisation that these motorcycles are appreciating classics.

Specifications: 1972 Kawasaki H2 (Mach IV)

Engine: Three cylinder in line two-stroke. Piston-port induction, 120 degree crankshaft throws.

Bore and stroke: 70mm x 62mm = 748cc

Power: 74hp at 6,800 rpm

Torque: 7.9 kg-m @ 6,500 rpm

Carburettors: 3 x 32 mm Mikuni.

Transmission: Five speed, straight cut primary gears, chain final drive.

Brakes: Front: 296 mm single disc Rear: 200mm Drum.

Fuel tank capacity: 17 litres

Dry Weight: 205 kg

Tyres: Front: 3.25 x 19 Rear: 4.00 x 18

Top speed: 195 km/h.

Price in 1972: Australia $1,399.00