From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 77 – first published in 2018.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

1965 was a big year for Honda. The company lured the world’s top rider, Mike Hailwood, away from MV Agusta with a deal to contest the 250cc, 350cc and 500cc World Championship classes for the 1966 season, and boldly ventured into the ‘big bike’ market with its revolutionary CB450. Today, the 450 is regarded as a middleweight rather than a big bike, but back then it was aimed directly at the segment of the market so long the domain of the British big twins.

The parallel twins offered by BSA, Triumph, Matchless/AJS, Norton and Royal Enfield were themselves aimed not so much at the home market, but the USA, where they cut serious inroads into Harley-Davidson’s territory. Honda wanted a chunk of that, but initially at least the CB450 failed miserably in USA, due more to the styling that the specification. Ironically it was a big hit in the UK. The poms loved it so much they even nick-named it the Black Bomber, despite the fact that it was also available in red. There’s no doubt the new 450 was a spirited performer, and when it was released in February 1966, it enjoyed a sizeable price advantage over the British 650s, selling for just £350 in UK. Early road tests showed the 450 could sail past the magic ‘ton, which was not bad for an engine of just 444cc, but there were other issues that seriously polarised opinion.

The Americans hated the look, particularly the humpy fuel tank. It was no lightweight either, tipping the scales at 187kg – 20kg more than a 6T Triumph. And whoever selected the ratios in the four-speed gearbox was clearly out of step with what was required. Around town, the 450 was a chore, with an ultra-low first gear (18.58:1) and a yawning gap to second (10.79:1). This was not so much a problem when changing up – the torquey engine bridged the gap nicely – but changing back from second to first in traffic was akin to throwing out an anchor. Ground clearance was a problem as well, both the footrests and centre stand easily made contact with the road when the machine was heeled over.

Seeking to prove the CB450’s worth on the race track, Honda, via its UK dealer network, tried to enter the ‘Black Bomber’ in the prestigious Brands Hatch 500 Mile Race in 1966 – but the entry was vetoed when the F.I.M. (who controlled the International regulations for the race) banned it on the basis that it was “too advanced”! Clarifying the reasons for their curious decision, the organisation stated that the use of double overhead camshafts in a production machine required specialised servicing techniques that were beyond the average owner and not in the spirit of Production Racing. It was seen by many as a back-handed compliment, and by others that the home fare was somewhat primitive. Honda did manage to steal some thunder by flying in Mike Hailwood from the previous day’s Dutch TT, and he was permitted to cut a few ‘demonstration’ laps on the CB450 prior to the start of the 500 Mile Race.

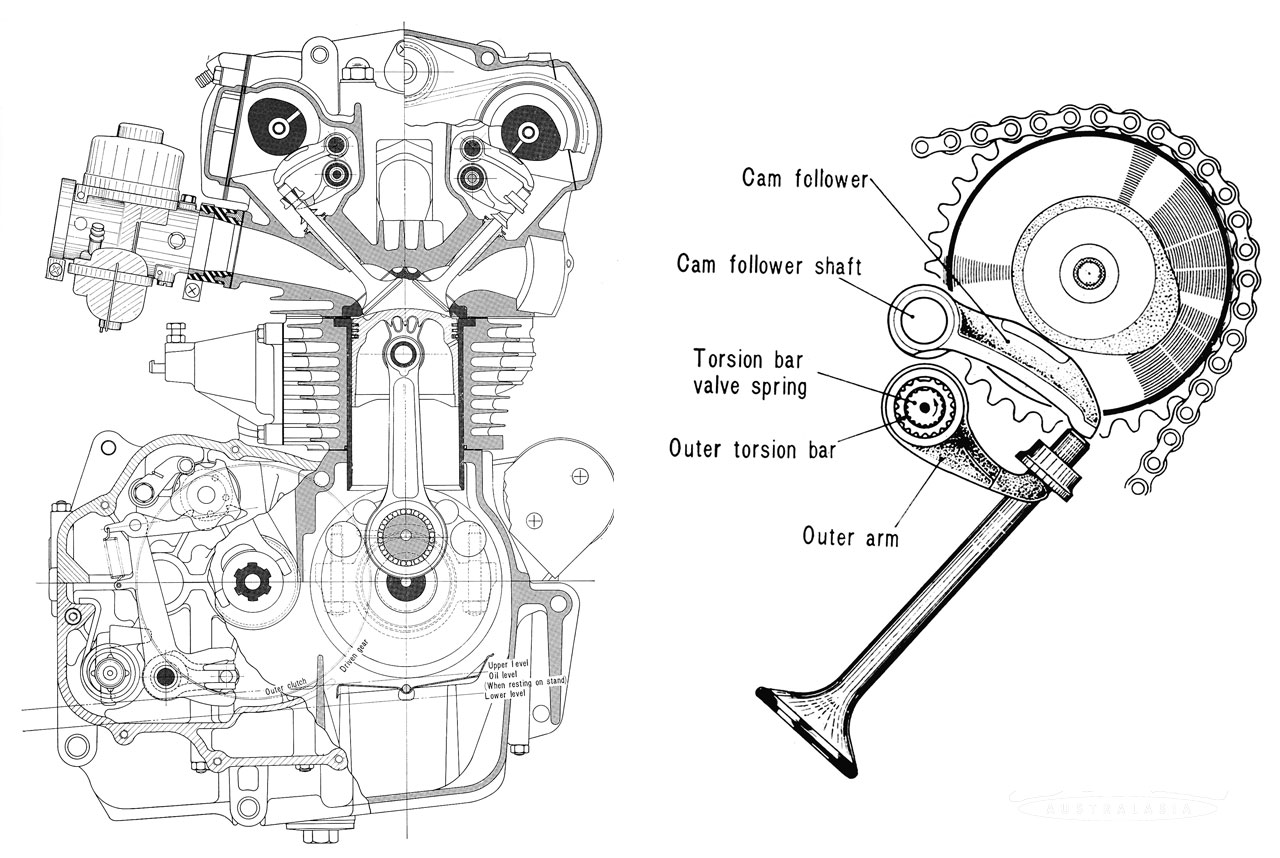

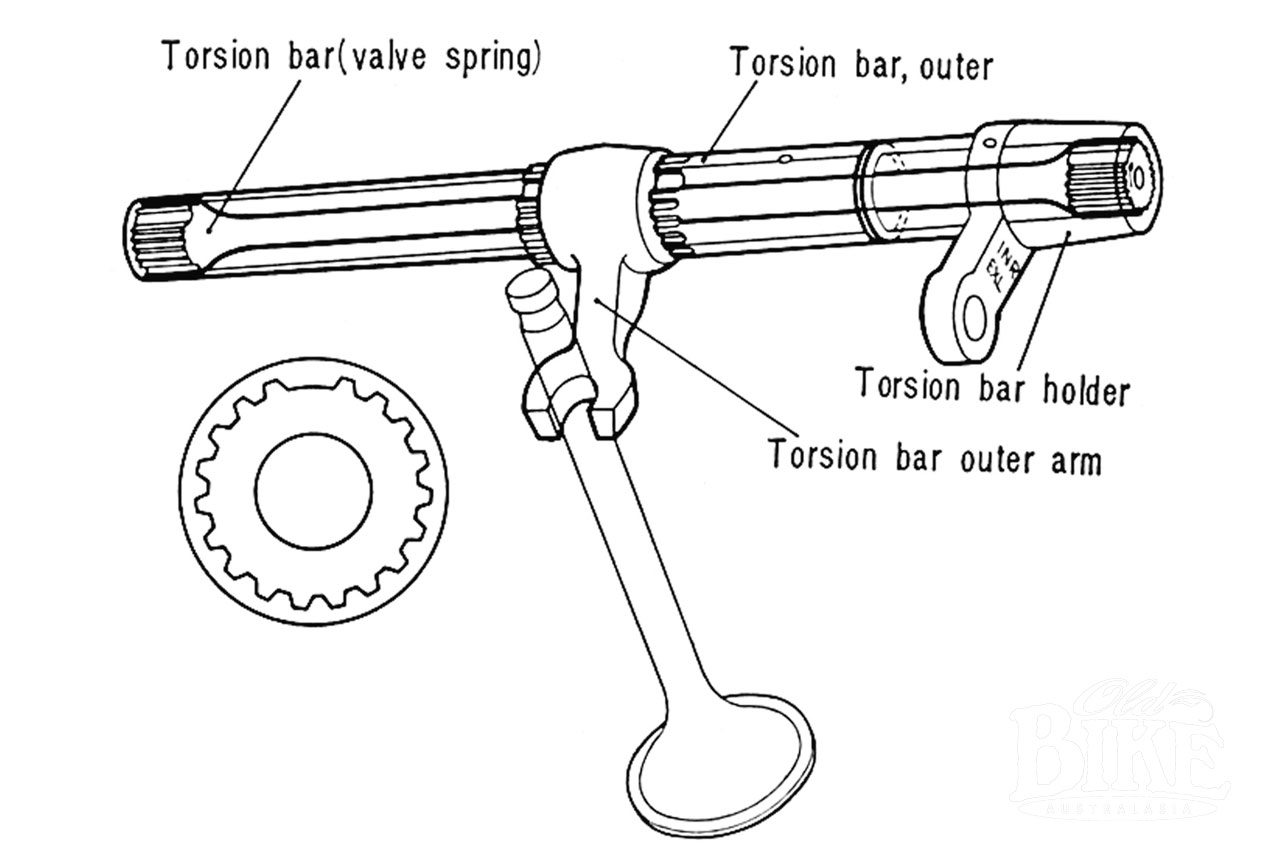

That engine, with its much-appreciated electric starter, featured a 180º four-bearing crankshaft, twin overhead camshafts and highly unusual torsion-bar valve springing, which enabled a 9,500 rpm red line – unheard off for a big twin at the time. Naturally, much was made of the torsion bar valve springing by the excited press, but in reality a conventional valve spring is actually just a torsion bar wound into a helix. Nor was the idea all that new. French Panhard Dyna cars of the early 1950s featured such a system in their 850cc opposed-twin engines. Honda also tried the system in their V12 Formula One engines, but discarded it in favour of helical springs. In the CB450, the camshaft lobe acts directly onto the rocker arm, while the valve is retained by a forked arm which itself is anchored to the torsion bar. The bar simply twists along its length to provide springing. One side effect of the system, not entirely desirable, is very high seat pressure, and the valve spring torsion bar also has a very finite life; shorter than helical springs. There is, however, a saving in weight over the normal helical spring and collet arrangement.

In a departure from usual Honda practice, the camshafts were supported in bearings contained in end plates on the cylinder head rather than running directly onto the casting or by the ball bearings used in the CB77. Crankcases were horizontally split, with the crankshaft supported in four roller bearings.

The impressive specification failed to translate into sales in what was intended to be the primary market, USA. Honda America’s National Service Manager Bob Hansen lobbied the factory to produce a racing version in order to demonstrate the model’s performance capabilities, and the result was a small batch of hand-built racers that were entered for the 1967 Daytona 200. They were fast all right, recording 137 mph on the bankings, but all four entries suffered problems of various sorts.

A gear up

Revolutionary as the CB450 was, more work was needed, and by November 1967 a completely new version, the K1, broke cover at the Earls Court Show in London. Most importantly, a fifth gear was added, virtually between the existing first and a slightly raised second (12.58:1), which transformed the riding experience as there was little need to go back to first other than for a complete stop. There were changes within the engine too, with larger inlet valves (up from 35mm to 37mm) and exhaust valves (from 31 to 32mm) and compression increased from 8.5:1 to 9.0:1. In search of a smoother power delivery the Keihin CV (constant vacuum) carbs dropped from 36mm to 32mm, but despite this, power rose to 45hp at 9,000 rpm. Styling also changed, with the old humpy tank replaced with a squarish version with chrome plated side panels, along with redesigned metal side covers with metal badges. The combined speedo/tacho (mounted in the headlight shell) of the 4-speedmodel gave way to separate instruments, with a smaller headlight, lighter chrome-plated mudguards, and increased ground clearance. Although the rear suspension units were redesigned, they still came in for criticism from road test journalists. The front fork was also new and a marked improvement on the original, with the 200mm drum front brake retained. At the 1969 Isle of Man TT, Graham Penny caused a major upset by winning the 500cc Production Race on a CB450K1, beating home TT specialist Ray Knight’s Triumph twin at an average of 88.18 mph. The K1 also hit the headlines by being officially the 10 millionth Honda motorcycle produced, with Soichiro Honda himself riding the motorcycle off the production line.

In 1969, Honda introduced the CB450K2, still with the drum front brake and 18-inch front wheel but with styling similar to the all-new CB750. The chrome sided tank had proved unpopular in USA, and was replaced with a design similar to the CB750, in candy red or blue with gold striping. The side covers also changed shape, with new ‘450 DOHC’ badges. Introduced with the 5-speed model was a US-version called the CL450, with gaudy high-mounted exhaust pipes on the left side, raised handlebars, and abbreviated mudguards which retained the drum front brake for its relatively short existence.

The same basic specification continued for the CB450K3, introduced in 1970, but with one major update – the front end. New forks, fitted with rubber gaiters, carried a 19-inch front wheel with a single disc front brake which was identical to the rotor on the CB750 and used the same caliper. As well as the K2 red and blue, candy gold was added to the colour choice. The oval-shaped mufflers that had adorned all previous CB450s were replaced with attractive tapered reverse cone megaphones.

Apart from new badges for the side covers, there was little change for the K4 model, although a mid-green with gold stripes was listed in some markets, with some fuel tanks sporting a chromed plastic bottom strip, as on the CB750. The USA K6 version of 1974 gained the redesigned petrol tank paint scheme from the K5 CB750, and this continued into the final version, the CB450K7. The CB450 was deemed to have run its race by the end of 1974, but was replaced for the next two years with the CB500T, which despite the increased capacity was slower and heavier. In most markets, this model was finished in a highly unpopular brown – the décor even extending to the seat cover –although red and a burnt orange was also available in some countries.

Just a cup of fuel…

Australian Terry Dennehy, was according to his brother in law Ross Hannan, “a sensational rider”, and after some success at home, he lit out for Europe with Ross’ brother Ralph. On self-built Hondas derived from CB72 and CB77 roadsters, Terry had occasionally shocked the established stars, but more often than not, the over-taxed engines gave out. Terry and Ralph spent the winter of 1967/68 in England but detested the weather, so they headed for Milan, where they met Swiss engineer Marly Drixl, who was making a name for himself as a chassis designer in conjunction with British importer Syd Lawton. Over numerous coffees in a local café, Terry, Ralph and Marly drew up plans for a 500cc Grand Prix racer to be powered by a new Honda CB450 engine, which was donated by a German enthusiast. The project was funded by off-loading Terry’s CR93 125 Honda and his Aermacchi Metisse, and into the new Honda engine went a special crankshaft, con rods, Aermacchi valves and valve springs (to replace the standard torsion bar set up), and – unusually for a motorcycle – a 45mm twin-choke Weber DCOE carburettor from an Alfa Romeo car. The bore was increased by 4mm to 74mm with the stock 57.8mm stroke to measure 497cc. The result was 65hp at 10,200 rpm at the rear wheel on a machine that weighed 129kg dry – more than competitive. One Honda item that was retained was the points ignition, and this proved to be the engine’s Achilles Heel.

Many a time the Drixton (Drixl/Lawton) Honda rolled silently to a halt with victory within sight, notably at the 1969 Finnish Grand Prix when Terry had successfully dealt with Giacomo Agostini’s works MV Agusta. Three weeks prior to this he suffered the heartbreak of running out of petrol while leading the East German Grand Prix at Sachsenring, letting Agostini through for a fortunate victory. It was a shattering moment; just a litre more fuel and he would have trounced the mighty MV/Agostini combination on a bike dreamed up in a coffee shop, and which still exists in Holland. Broke and disillusioned, Terry abandoned the Honda twin to eventually end up on one of the ubiquitous 350 Yamahas. What might have been…

A workhorse

Nowadays, the CB450 is considered a desirable classic bike, with examples of the first model bringing consistently high prices. There is no doubt that the 5-speeders are much more practical and usable, and one that has been in constant use for just such purposes for many years belongs to Richard Steain, who with twin brother John was a leading light in Lightweight production racing in his day. Although his racing days are now behind him, Richard is still a hard bloke to keep up with in rallies – and he shows his CB450K5 no mercy!

When testing the CB450K3, the respected Cycle World magazine described the machine as “still the most technically advanced standard production four-stroke motorcycle available in the world today.” Strong words but hard to refute. And although the temptation to bury the 450 in the face of Honda’s push with the four-cylinder range must have been strong, the company persevered with the twin and gradual refinements made each subsequent model a better machine. For the K4, the front end was revised with the scrapping of the CB750 front end for components sourced from the CB500, including the smaller front disc with its black caliper.

“I bought mine from a guy in the Macquarie Towns club for $700 about 15 years ago”, says Richard. “It had a spare motor, was painted black and had ape-hangers (handlebars), Dunstall copy megaphones, and the front mudguard was cut off halfway. It had the usual problems, one piston was peppered through detonation, the cam chain was stretched, and a few other things. My mate Steve Andersen was a mechanic at Burrill Lake – he was a bush mechanic and could fix anything, so we got all the bits, put it together and rode the wheels off it. They have a crap ignition, it’s all over the place, because the springs are too weak and the bob weights are not big enough to hold it on full advance. I put an electronic ignition on it – a Pazon from New Zealand – and it transformed it. Now it would idle perfectly and there were no flat spots and it no longer overheated when ridden hard. I took the head steady off it, and it’s pretty lumpy up to about 3,500 rpm, but you’re usually above that anyway, but once it gets above that the mirrors don’t blur and you can just rev it to whatever you like. With the headsteady on it transmits the vibration to the top, whereas without, it transmits it to the footrests. 100km/h in top gear is 5,000 rpm and it’s smooth. I have a K5 brochure and it says 41 horsepower at 9,000rpm – the earlier ones were stated at 45 – and all the road tests said 45 hp for the later models. At that stage to 500/4 was out and that was 50 horsepower at first, but gradually went to 48. So they couldn’t have a 450 twin – supposedly with around the same horsepower – going quicker than a 500 four, could they? I don’t understand the 450’s gradual drop in stated horsepower because over the 5-speed models there was no difference in the pistons, the camshafts, the carburettors – the things that make the difference to the power.”

Visually, Richard’s 1972 K5 differs from the earlier models by the shape of the petrol tank, which has a chrome bottom strip, and, if you can pick it, the CB500 front end and a slightly altered seat. Otherwise, it’s just a logical progression in the model that began with the fabled Black Bomber in 1965 and concluded with the K7 a decade later. And as owners of these highly sophisticated motorcycles will attest, the 450 is an excellent and often underrated machine.

Specifications: Honda CB450K5 1972

Engine: All alloy parallel twin cylinder, chain-driven double overhead camshafts with torsion bar valve springing.

Bore and stroke: 70mm x 57.8mm = 444cc.

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Power: 41hp at 8,700 rpm

Transmission: 5-speed

Carburation: Two 32mm Keihin constant vacuum.

Starting: Electric or kick

Frame: Tubular steel semi-double cradle

Tyres: Front: 3.25 x 19 Rear: 3.50 x 18

Electrics: 12 volt

Weight: 179 kg

Wheelbase: 1375mm

Tank capacity: 16 litres