From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 65 – first published in 2017.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Sue and Jim Scaysbrook, Alan Stone.

We’ve all sold bikes and then regretted it. In Bob Rosenthal’s case, he got a second chance to own a motorcycle that he now cherishes.

As an aspiring racer, Paul Dunstall made do with a lightly modified 600cc Norton Dominator twin, his on-track career beginning in 1958 while he was working at his father’s motor scooter shop in Eltham, South London. Coincidentally in the same year, Nortons themselves had finally accepted that the venerable Manx single’s days were numbered and was experimenting with a possible replacement – the twin cylinder Domiracer. Three years later, Paul had abandoned any ideas of becoming a star racer himself, handing his Norton to sometime GP rider Fred Neville, Neville was killed in the 1961 Manx Grand Prix when riding a 7R AJS, and Dave Downer took over the reins of the Dunstall 600.

When the Norton Race shop was closed down by AMC in 1962, he was offered the works Domiracer that had lapped the TT course at 100 mph in the hands of Australian Tom Phillis. A price was agreed, but when Paul and Dave drove their van to Birmingham to collect the bike, virtually the entire contents of the shelved Domiracer project was loaded into the back of the van and they were sent on their way. Dunstall was fascinated by the development that had gone into the racing twin, and incorporated much of the thinking into his own machine. In addition to his duties in running the scooter shop, a thriving trade in Norton go-faster bits began to develop from the shed behind the shop. Swept-back pipes, twin-carb conversions, high compression pistons, clip-on handlebars and the like flowed forth to an eager clientele.

Eventually a complete Norton Dominator received the Dunstall treatment, and orders for converted new Nortons came in quickly. Over the next few years, Dunstall’s contribution to each completed motorcycle increased to the point that the machines were more Dunstall than Norton, and this enabled him to gain recognition from the Board of Trade as a manufacturer in his own right. This decision also enabled the Dunstall Nortons to be eligible for UK Production Racing, including the Isle of Man TT. In addition, several racing bikes were created using the ex-works ‘Lowboy’ frames from the Domiracer.

When AMC introduced the 750cc Atlas, it gave Dunstall the opportunity for a capacity boost and increased performance. To publicise the new 750 Domiracer, a machine was taken to Monza in Italy where it thundered around the old banked circuit ridden by Rex Butcher, covering 126.7 miles in one hour. Along Monza’s bumpy straights, the 750 was electronically timed at 143 mph, with the bike in full road trim including silencers and lights and fitted with Dunstall-made twin disc front brakes and his own design of full fairing. By 1967 he had managed to extract 67.5 bhp – an increase of 10% over standard – from the engine, along with a weight reduction of 22 kg over the standard Atlas. With Ray Pickerell in the saddle, a Dunstall Atlas captured the 1968 750cc Isle of Man Production TT at an average speed of 98.13 mph.

Dunstall’s dalliance with Norton continued way past the Featherbed era and into the Commando stage, during which time the capacity was increased to 810cc with the addition of a light-alloy cylinder block, and performance boosted further by Dunstall’s own silencers, which were marketed under the Decibel brand. By 1973 he was shipping complete bikes to several overseas markets, primarily to USA but also to Sweden and Australia. The official Australian distributor was Motor Cycle Racing Industries in Sydney, with state agencies Athoil Patterson in Melbourne, Pittmans in Adelaide, Morgan & Wacker in Brisbane, and Mathews Cycle World in Perth. Paul was also astute enough to realise that the end was nigh for the British product, and began supplying bolt-on accessories for the Honda CB750, Kawasaki Z1 and the GT750 Suzuki. This continued into the early ‘eighties, when Dunstall sold the naming rights of his products and left the motorcycle scene completely. With the proceeds from the sale, Dunstall purchased a stately house at Shoreham, near Sevenoaks, and became a successful property developer in Britain and Spain.

The bike that came back

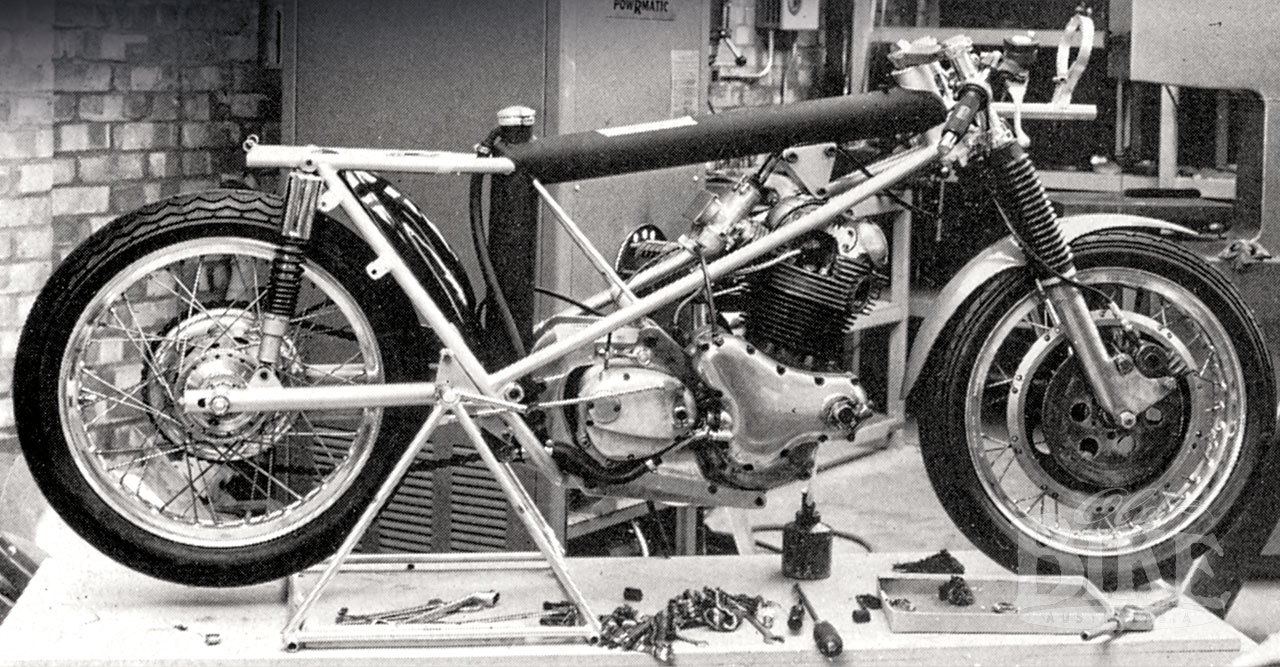

The featured Dunstall Atlas was originally brought to Australia by Athol Patterson in 1964, who had a shop in the eastern Melbourne suburb of Springvale, which did good business in a range of motorcycles including AJS, Cotton, Metisse frame kits, Montesa and Norton. The bike was in fact a standard Norton Atlas SS, and as the UK Police had used Norton twins in various forms, Patterson loaned this machine to the Victorian Police force for appraisal, but perhaps unsurprisingly, they found it unsuited to their needs and returned it after three months. It was then sold to the Atherton brothers who used it for Production racing, without a great deal of success and a fair amount of mechanical trouble, including crank and main bearing problems. In a dismantled state, it was later traded in on a Cotton Telstar to John Armstrong, who ran Armac Racing Service, selling a range of performance and racing gear. Eventually, Armstrong reassembled the Atlas, and found a customer in up and coming road racer Bob Rosenthal, who takes up the story.

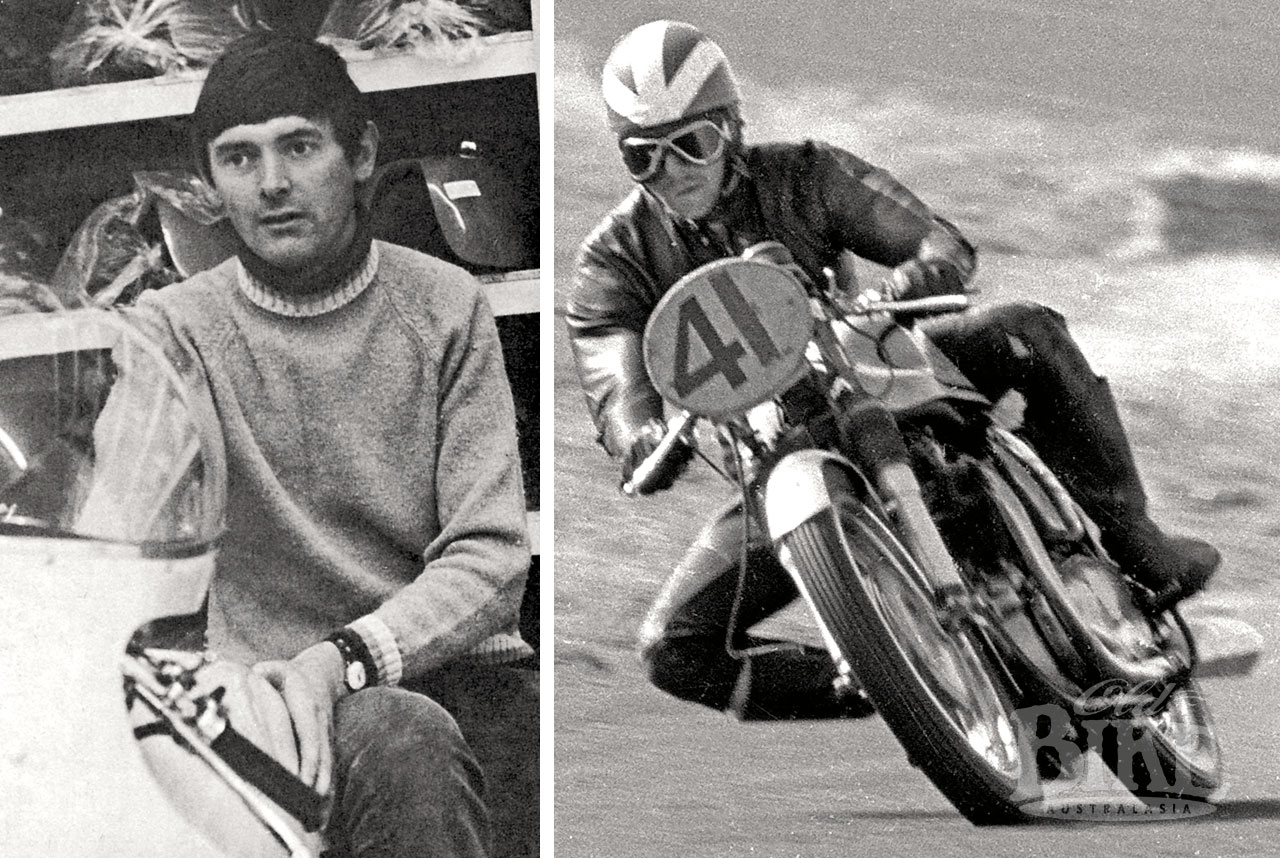

“I bought the Atlas in 1966, and started racing it immediately, as well as riding it to work every day. Athol Patterson made me an offer where he sold me all the Dunstall stuff at his cost, provided I entered it as a Dunstall Norton. So I did and that bike got me through to B Grade but they didn’t like me entering it in A Grade races because it was still a registered road bike. I raced it from 1966 to 1969 when the TR2 Yamaha came on stream. I parked the Norton and didn’t use it again until in 1975 a guy who I worked with offered to buy it. I watched him ride away on it and thought ‘what the hell have you done, you idiot!’ I always regretted selling it.”

Bob may have rued his decision, but his racing career had progressed to the point that he was now the mainstay of the Motorcraft Team Milledge Yamaha squad, with a pair of well fettled Yamaha TZ750s to race, which he did very successfully until he retired at the end of 1978. Years went by with a growing interest in touring with his wife Lynne. This included several major rides in USA and Europe on BMWs, and later still, a return to racing in the Historic ranks on a Manx Norton and a Matchless G50. Still, the Dunstall had never been completely forgotten, as Bob explains.

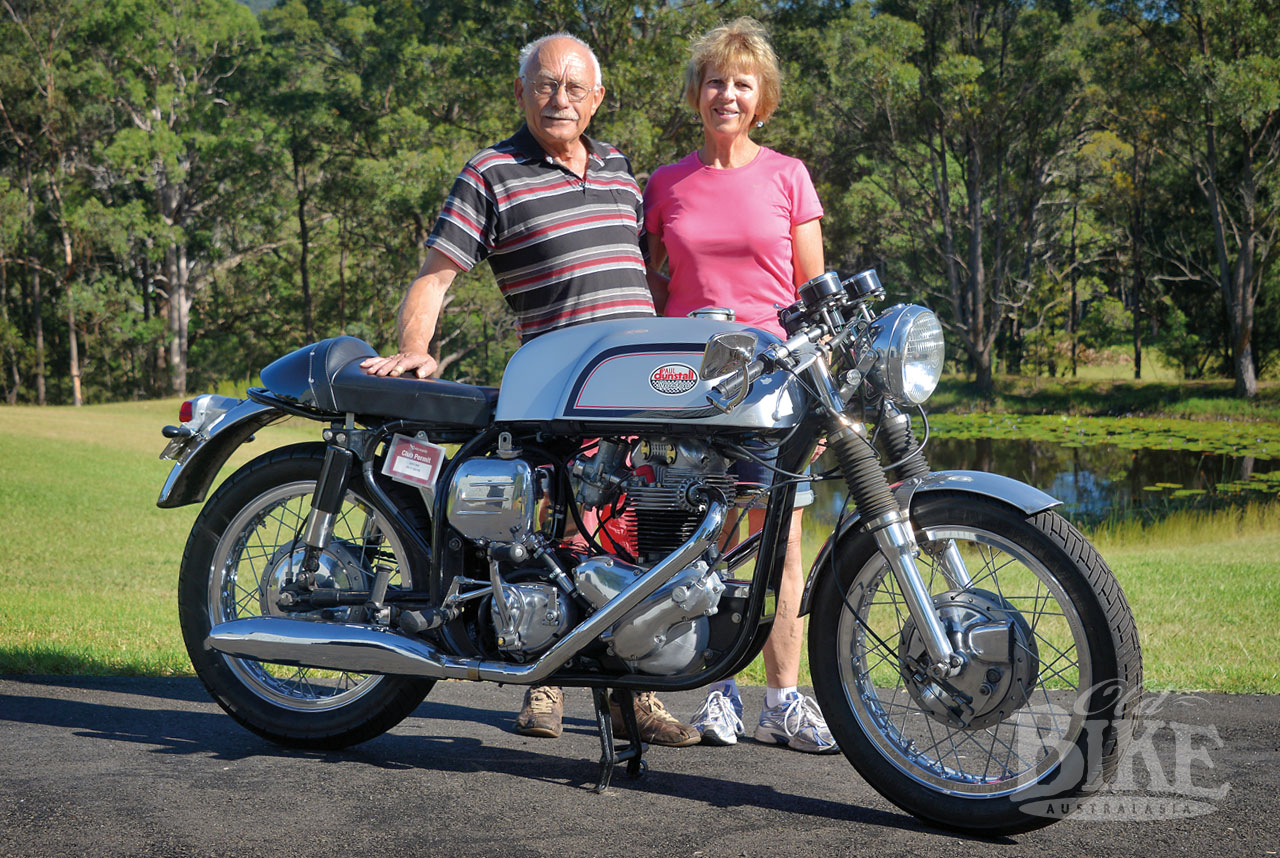

“In 2005 I found out that the guy I had sold it to 40 years before still had it, so I made him an offer and I’m glad to say he accepted it. Basically what I bought was 15 cardboard boxes of rust. He had moved to Sydney and lived near the harbour. He had pulled it all apart, wrapped it in dry newspaper and put it under his house where it sat for 15 years so it was in a pretty sad condition when I got it. What I wanted to do was to correct a mistake; that I should never have sold it in the first place. So when I retired a couple of years later I built myself a decent workshop and set about restoring it, which took me four years. When I sold it, it had Dunstall pipes, seat tank, Tickle twin leading shoe front brake, and Hepolite 9.0;1 pistons instead of the original 7.6:1. The only internal engine components I put in were the pistons and double-speed oil pump drive gears, because that was a bit of an Achilles heel with the Atlas, they just didn’t have enough oil going around.

“When I raced that bike in Production and B grade races, I found it to be pretty much the quickest bike around. I wanted an Atlas because they had the pedigree of a Featherbed frame and the Atlas engine, and if it was carefully set up, was a rocket in its day. I remember the Atlas advertising at the time, ‘If you want the fastest standard production motorcycle in the world’ – and it was. There wasn’t a Triumph or BSA at the time that could stay near it. But it vibrated because it was originally designed as 500 in 1949 as the Model 7 and 77, 88 99 600 and later 650, and as they went bigger everything was relatively OK until they went to 750cc in the Atlas and that was a step too far. That was why the Atlas came out with 7.6:1 compression; they dropped the compression to cure the vibration. They would rattle themselves to bits. The vibration with the standard balance factor was so bad that bits would undo and fall off or crack and fall off. Probably they could have done a bit more engineering into the balancing of that motor. When I restored it I changed the balance factor from 87% down to 70% and it makes a much better normal street engine. The bottom end was the same as a 650 but with the bigger pistons, so the same balance factor couldn’t be right for both engines.

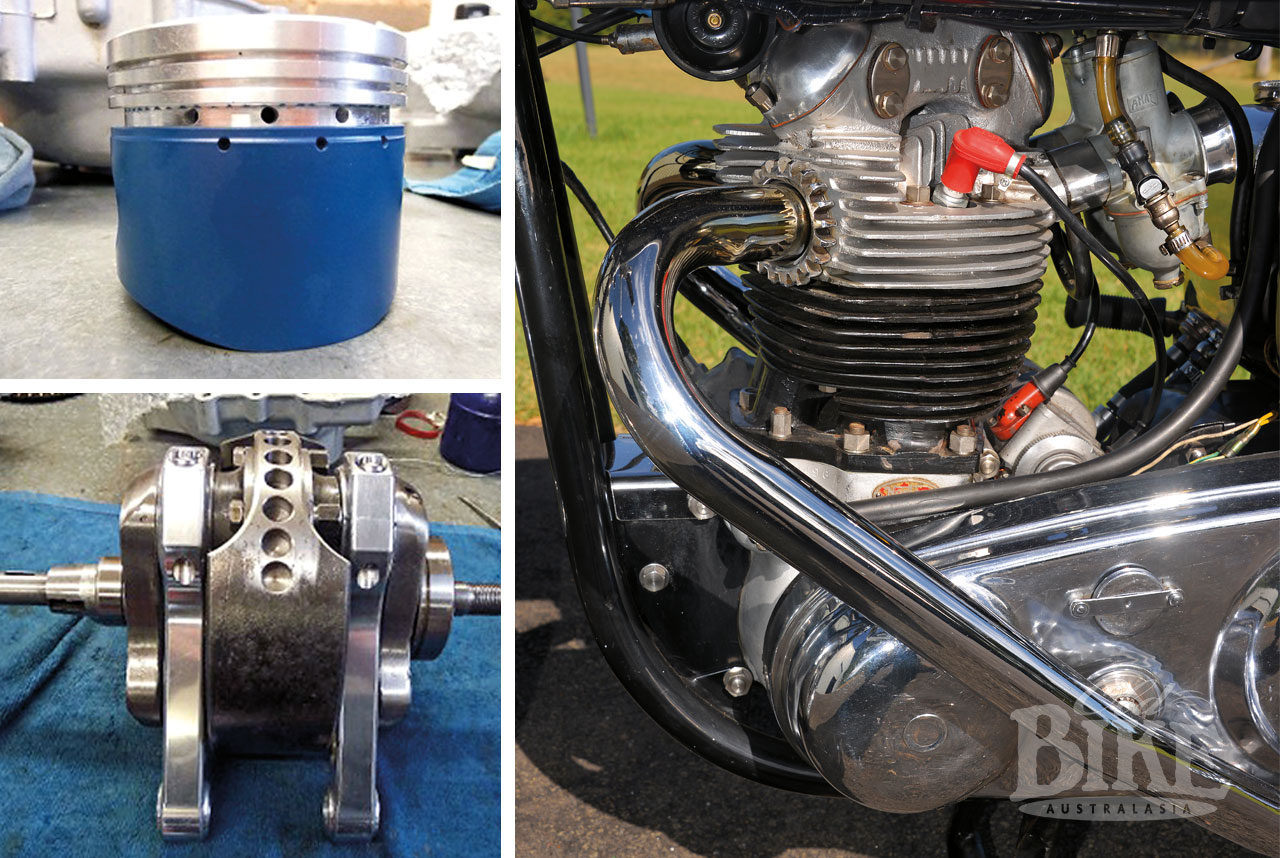

“The fellow that I got to do the crankshaft for me was called Clint Kone; he raced quite successfully an Atlas engined outfit. We talked about balance factors and I know Dunstall used to change his factors back to about 70. From about 2 and a half to 5 thousand revs it’s fine, but after that your fillings had better be glued in because they’re not going to be there long otherwise. When I put it together I used American MAP conrods, all alloy rods, even the big end cap is alloy, beautifully engineered, from Florida. They guarantee their rods to 200 horsepower per rod, and that makes the bottom end bomb proof. The conrods in the standard engines were always a weak point, especially the early engines, they used to snap the rods just above the big end. They changed that in about 1964 with a more gradual webbing and that worked OK. I used to put a new set of rods in every year and used to polish the rods to a mirror finish and make sure the rods didn’t clunk against the crankcase mouth. That made quite a bit of difference. They were alloy rods with steel big end caps. A lot of people now run Carillos which are OK but when I first saw these MAP rods I thought that’s for me. The pistons came from Vintage Motorcycle Pistons, UK.

They are made to Hepolite specifications, but with oil ring holes, not slots. They are actually made in Adelaide. I had them ceramic coated to get the skirt clearance that I wanted. Valves, springs and guides came from Norvil, UK., who also supplied the belt primary drive and clutch. The head work was done by Speed Works in Ringwood, Melbourne. Exhausts from Armour Motor Products, UK, are the best repro units on the market. Some hardware and nuts and bolts to original threads I bought Molnar Precision Ltd. UK. Molnar’s nuts and bolts are all stainless steel and done to the original 26 TPI thread count. I also got various sundry parts from Modac Motorcycles in Melbourne. The fuel tank was repaired and painted by Matty Johnston in Melbourne, Matty worked magic with the tank. Dunstall tanks of that period are no longer made, and this one was in very poor condition. The stickers and transfers were supplied by Classic Transfers, UK. HydroBlast, in Sandringham, Melbourne did the alloy cleaning.

“The Norton originally came with two 1 3/16” Amal Monoblocs. When these wore out, as they do, I put a pair of 30mm Concentrics on, exactly the same as a Commando and they worked OK, but when I restored it I bought a brand new set of these from Amal in UK, but I have never been happy with them. I am seriously toying with changing it over to a single 34mm Mikuni. It carburates fine everywhere except idle and I just cannot get it to idle. It had a Lucas Competion magneto – that’s what the Atlas came with – and it has been rebuilt since then which throws a spark big enough to weld from so why go to a battery ignition? The head is standard Atlas, springs, cam, six-start worm instead of three-start worm in the oil pump which Norton went to in 1966. Gearbox is standard but converted to tooth belt rather than chain primary drive. This came with a new Commando clutch which seems to work fine as a road bike, and I will never race it again. The belt drive eliminated the only oil leak I still had. Perfect. What I now have represents four years work and I love it.”

At its present pace of life – the annual All British Rally at Newstead plus one or two club runs – the Dunstall Atlas will grow old gracefully. But after being thrashed mercilessly in its early days, then spending nearly two decades rusting away in cardboard boxes, it’s earned a leisurely retirement.

Riding: A blast from the past

With Bob’s words of warning ringing in my ears, I approached the Atlas with a degree of trepidation. One lusty kick is all that is required to bring 750cc of Britain’s finest into life, and a somewhat irregular tick-over idle is eventually achieved once the engine and its lubricant warms up. This is a machine built for sprints between (human) refuelling stops, and comfort is not the primary consideration. The rear suspension is as soft as a brick, and the seat sparsely upholstered, so don’t expect a plush ride. Having said that, the front end is quite pliable, so the overall riding experience is better than many a café racer.

The standard AMC ratios are low first and second, with a sizeable gap to third and fourth (top), but the shifting is effortless and precise. Coupled to the Bob Newby clutch and belt drive, it adds up to a benign transmission, where the clutch action is wonderfully light and faultless in its operation.

So, out onto the open road we go, that big twin rumbling happily below. Once under way, all feelings of cramped confines disappear – even the clip-ons feel well placed and comfortable. The carburation is spot on and the engine pulls like a D9 – top gear does everything. Naturally, the Atlas comes alive at the first sign of a corner, and fortunately my route through the lower Blue Mountains had plenty of them. The handling is beyond reproach, razor sharp. The exhaust note rising and falling though the hills is pure music. Mention must also be made of the front brake, which is a John Tickle twin leader backing plate in the Norton drum (similar to the early Velocette Thruxtons) and works a treat – a single finger job at low speeds and perfectly progressive and powerful for demon braking should it be required.

Sure, there’s a certain amount of vibration buzzing through the seat, but it is not unpleasant, and hey, this is a sports machine in the truest sense of the word. And if it were to miraculously appear in the forecourt of the Ace Café, you’d be knocked down in the rush just to ogle it. A Dunstall Atlas is that kind of motorcycle.

Original Specifications: 1964 Dunstall Atlas Norton.

Engine: 745cc ohv parallel twin.

Bore x stroke: 73mm x 89mm

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Crank: Roller bearing drive side, ball bearing timing side mains, plain big ends.

Transmission: 4 speed

Ignition: Lucas magneto with auto advance.

Charging: Lucas 100-watt alternator. 2 x 6 volt 8ah batteries in series through rectifier.

Tyres: Front: 300 x 19 Avon Speedmaster MkII. Rear: 350 x 19 Avon Grand prix with Dunlop alloy rims.

Brakes: Front: 8 inch twin leading shoe. Rear: 7 inch single leading shoe.

Suspension: Front: Norton Roadholder forks. Rear: Girling units.

Fuel capacity: 5 gallons (22.7 litres)

Wheelbase: 1410 mm

Seat height: 788mm

Weight: 390lb (177 kg).

Dunstall equipment

Engine: Twin 1 3/16” carburettors, bronze valve guides, polished inlet tracts, lightened rockers with pressure oil feed. Lightened cam followers.

Cycle parts: Fibreglass fairing; swept-back exhaust pipes with megaphone silencers; fibreglass dual seat; rear set footrests; gear change linkage and rear brake lever; clip-on handlebars with alloy ball-end levers; straight-pull twistgrip; steering damper; light alloy top fork yoke; rubber fork gaiters; light-alloy mudguards; racing brake linings; chrome-plated oil tank, battery box cover, primary chaincase, instrument bracket, headlamp shell and mounting brackets, rear chainguard and suspension springs.