Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

Ducati did some strange things in the 1960s, struggling, as it was, to remain in existence. In fairness, many, if not most of the shots were called by its American distributor, the Berliner Corporation, and unlike its compatriot firms, it had to dance to the tune of its owner, the Italian government.

The 250 and 350 singles had sold well in the States, but Berliner wanted more – something for the larger capacity market – and they wanted it quick, in the face of a steamrolling assault by the Japanese, particularly Honda. The reasoning was there; in the early part of the 1960s, the Japanese were concentrating their efforts in capturing the lightweight end of the market, and, with a few discountable exceptions, had not yet turned their attention to middle or heavyweight motorcycles. But they soon would – the CB450 was coming.

Berliner reasoned that it was no bad thing for the Japanese to stimulate the lower end of the market, because while the nicest people were meeting each other on Hondas, a percentage of these would look to graduate to something larger, sportier, faster. The trick was to be ready when this generational swing occurred. The British, of course, were busily playing themselves out of the game; the traditional factories dropping like flies, and development virtually at a standstill amongst those that remained. Ducati, through Berliner, were not alone in seriously eyeing this rapidly maturing market. Laverda was hard at work on a Honda inspired 650 twin, and Benelli, with the energetic Cosmopolitan Motors stirring the coals in the US, was similarly engaged on a parallel twin of its own which became the 650 Tornado.

Back in Italy, there were plenty of drawings on the Ducati tables, ranging from twins to triples to fours, with all sorts of methods of driving the valve gear. But Ducati was State-owned, and the coffers were tightly controlled by politicians, not engineers, marketing people, or even motorcyclists. The saga of the ill-fated and hugely expensive Ducati Apollo four was under way at the time, so it was not an ideal occasion for the Ducati factory to come begging for more cash to develop yet another range of motorcycles, primarily destined for one, albeit important, market.

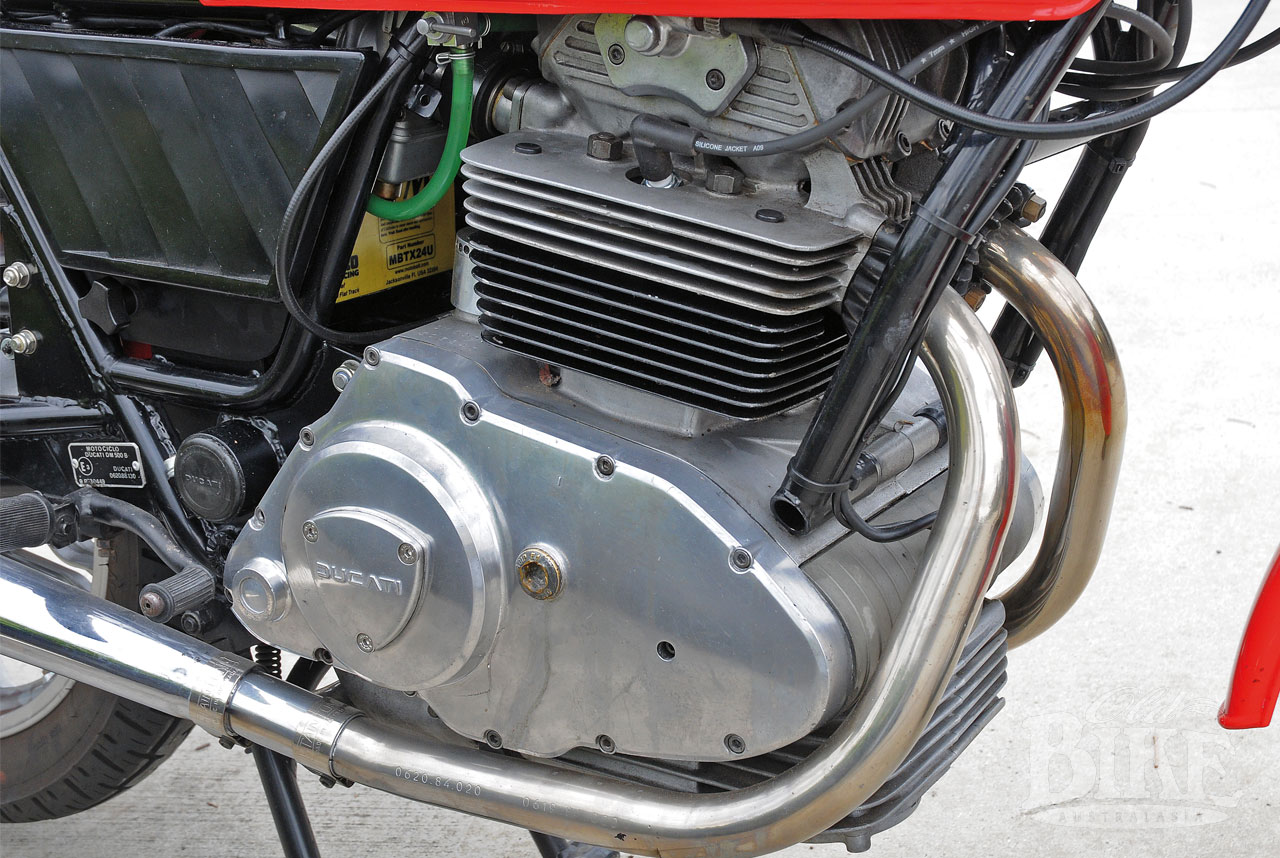

Ducati’s brilliant engineer Fabio Taglioni – never a fan of the parallel twin concept – wanted a modular OHC design with desmodromic valve operation; in 500cc form a triple that could become a 750cc four in due course. What the financiers agreed upon was a far cheaper option – a simple 500cc pushrod twin with a 360 degree crankshaft with twin balance shafts. Simple it may have been, but it was also fat, weighing in at close to 200kg, with only around 40 horsepower to push that bulk along. For a 500, the engine looked huge, and it was. The bottom end housed not just the crankshaft and the four-speed gearbox, but an electric starter, which poked out the front. It was wet sump as well, further adding to the massive structure. With bore and stroke of 72mm x 58.8mm, the twin should have been a willing revver, but peaked out at a fairly tame 6,500 rpm. When the prototype was shown to journalists at Daytona in 1965, the reaction was cautious, but there was no disguising the serious lack of ground clearance and the overall obesity. By the time the prestigious Daytona Cycle Week was finished, the Ducati was on its way back to Italy for a complete rethink.

For the next four years little was heard of the twin, but when it did finally reappear, it was not so much a makeover but a completely new machine, constructed without Taglioni, who refused to have anything to do with it. It was still a pushrod design, but with the bottom end totally changed; the starter motor now sitting above the gearbox, which now contained five speeds. Importantly, nearly 25kg had been shaved off by various economy measures, including the use of smaller and lighter Grimeca drum brakes front and rear. The frame was all new as well; a narrower, double cradle tubular job with the front down-tubes attaching to the crankcase. The smaller crankcase and narrower frame allowed the troublesome exhaust pipes to be tucked in closely. Although power was still short of 40hp, claimed top speed had crept past the 160km/h barrier, thanks mainly to the significant reduction in weight.

Improved though it may have been, the ohv 500 failed in one vital respect; the brass at Berliner refused to place a substantial initial order, preferring to wait until the rumoured 750 GT V-twin was ready. Once again, the 500 twin project ground to a halt, and whilst the 750 GT did soon become a reality, it was expensive to produce and added little profit to the company’s balance sheet. Despite market trends suggesting otherwise, Ducati’s lords and masters persisted in their demands for a 500 twin, and by 1975, ten years after the original was seen, the latest version was shown at the end-of-year Milan Show. This used a 180 degree crank, after engineers abandoned the 360 due to incurable balance and vibration issues. It was to be offered in three versions, all single overhead cam, one of which was a 350 with dimensions of 72mm x 43mm. The 500 came in two models – the GTL (Gran Turismo Lusso) and the Sport; the latter with the company’s signature Desmodromic valve operation on the chain-driven camshaft, which had four lobes to operate the cams as well as the desmo gear and slightly more overlap. Power outputs were 40hp at 8,000 rpm and 44hp at 8,500 rpm respectively. All ran 9.6:1 compression ratio. The top of the range Sport 500 had a top speed of 177 km/h while the 350s could manage 148. The 500s breathed through 30mm Dell’Orto PHF carburettors.

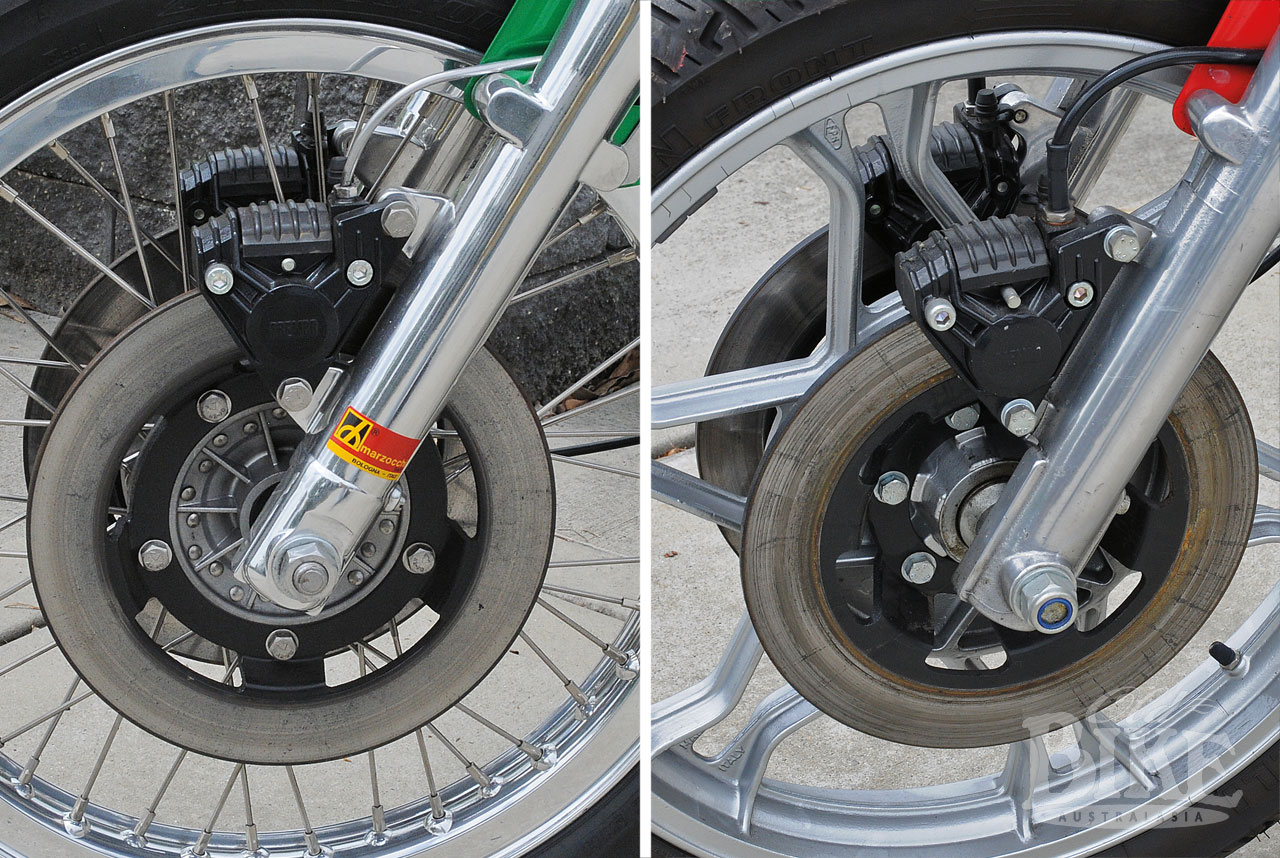

But although the twins were now deemed ready for production – and orders flowed in, especially for the 500 Sport – the company’s factory in Bologna was critically short of space due to much increased production of diesel engines. The solution was to transfer production – and the job of completing the styling – to Leo Tartarini’s Italjet factory on the other side of the city. Engine units were still built in Ducati’s factory at Borgo Panigale, then sent to the Italjet facility which supplied the chassis. The frames of the two 500s differed in that the GTL used a single front down tube while the Sport had widely splayed twin front tubes, with the engine used as stressed unit in both cases. Paioli 35mm forks and rear shock absorbers were used, with cast iron Brembo discs at the front. The GTL used a 160mm drum rear brake while the Sport had a single Brembo disc both ends. Rear chain adjustment was achieved by rotating eccentrics mounted at each end of the swinging arm pivot. A tool was supplied with each bike, this being inserted in the eccentric to provide a quick and accurate adjustment. The exhaust system was sourced from Lanfranconi. Soon a desmo version of the 350 appeared which was vital in the home market as motorcycles of 350cc or less received a more favourable rate of taxation.

In the production version, the oil for the wet sump engine was circulated by a gear pump for pressure feed as well as scavenging, but the lubricant itself had a hard life and the factory recommended it be changed every 5,000km – something that many owners failed to do, with disastrous results. The forged crank, with its two plain bearings and split-shell big ends, required clean lubricant and plenty of it, and the gearbox and helical gear primary transmission with its wet clutch shared the same oil, so dual oil filters – one a tubular nylon strainer and the other a replaceable paper element – were required.

On the electrical side was a crankshaft-mounted Motoplat 200W alternator, coils and transistorised regulator made by Ducati’s Spanish affiliate Mototrans company, with a set of points mounted behind the left cylinder where it was all-but inaccessible. Reliability was not a strong point, and with no kick starting option, failure of the electric starter resulted in a stationary motorcycle and an exasperated owner.

Despite all the pain and the decade long gestation period, the parallel twins were never successful; shunned by the Ducatisti as not being a legitimate part of the Ducati family. With Italjet only taking engine units as it required for forward orders, stocks of the power units piled up back at the Ducati factory until the plug was finally pulled on the model in 1983. The real death knell for the parallel twin had been sounded as far back as November 1977, when Taglioi’s brilliant Pantah v-twin, with the toothed belt camshaft operation first seen on the 1973 Ducati 500cc GP racer, was unveiled. However in typically defiant fashion, the factory responded with still another version of the parallel twin, the 500GTV. This model, introduced for 1978, was in touring style with the frame, wheels and engine (painted black) from the Sport Desmo, but different tank, seat and side covers. When the 500cc Pantah finally came on stream in 1980, it was the end of the GTV – almost. The factory had such a stock of unused parallel twin engines, it moved production back from Italjet to Borgo Panigale and kept up assembly until stocks finally, and permanently, ran out. This ended a saga that lasted 20 years, but is today a dim memory in the company’s history, and certainly not one that is celebrated with any gusto. Regardless of any technical comparison, the model’s insurmountable obstacle was always the price. In its late incarnation, the Sport was exactly double the price of the Honda CB500T – the 500cc version of their venerable and well built CB450.

A local pair

Stephen Craven is a global authority on Italian motorcycles and Ducati in particular; his business SCR at Morisset on the NSW central coast is always packed with rare and wonderful machinery undergoing everything from services and tuning to complete restorations. So it was a unique moment to find fully restored examples of both of the parallel twin 500s on hand when I called by one sunny day. Standing side by side, the difference between the two models become instantly obvious.

While the GTL’s styling is very reminiscent of the 860 GT, the Sport closely resembles the Tartarini designed Darmah. The GTL’s single front downtube frame also has a different middle section, being broader and beefier around the section above the swinging arm pivot. Unlike the early versions, both these bikes utilize Marzocchi front forks instead of Paioli, and in this case the Sport is fitted with alter-type Marzocchi rear shocks with remote reservoirs. The seat on the GTL is a much more plush affair than the thin-crust Sport’s offering; a point loudly voiced by Sport owners back in the ‘seventies as they struggled for comfort on anything but short rides. The GTL uses spoked wheels with traditional Italian Borrani aluminium alloy rims, while the Sport has FPS cast alloy wheels. Most noticeable is the rear set footrests, gear lever and brake pedal on the Sport, which also has Conti mufflers fitted, whereas Lanfranconi mufflers were originally standard on both models.

In the main, most other shared components are standard Italian fare for the time; Tommaselli twistgrip, Verlicchi grips, CEV switches. The featured GTL uses Smiths instruments, while the Sport has Veglia speedo and tachometer. Amazingly, both bikes were built in January 1977.

Our thanks to SCR Ducati, 4/6 Brodie St, Morisset NSW (02) 4973 4165 for the opportunity to photograph these motorcycles.

Specifications: Ducati 500GTL and Ducati 500 Sport Desmo

Engine: 497cc SOHC parallel twin, 2 valves per cylinder, desmodromic valve operation on Sport

Bore x stroke: 78mm x 52mm

Compression ratio: 9.6:1

Induction: 2 x Dell’Orto 30mm PHF carburettors

Ignition: Motoplat coil and battery

Starting: Bosch electric starter.

Transmission: 5-speed gearbox with helical gear primary.

Brakes: 2x 260mm Brembo front, single 260mm rear (Sport), 160mm drum (GTL)

Tyres: 3.25 x 18 front, 3.50 x 18 rear

Dry weight: 183 kg (Sport) 190kg (GTL)

Fuel capacity: 18 litres (Sport) 19 litres (GTL)

Chassis: Full cradle tubular steel (Sport), single tube cradle (GTL)

Suspension: Paioli front forks and rear shocks