Story: Jim Scaysbrook with assistance from Pat Slinn and Ian Falloon. • Photos: Ian Falloon, Gaven Dall’Osto, Phil Aynsley, OBA, Shannons

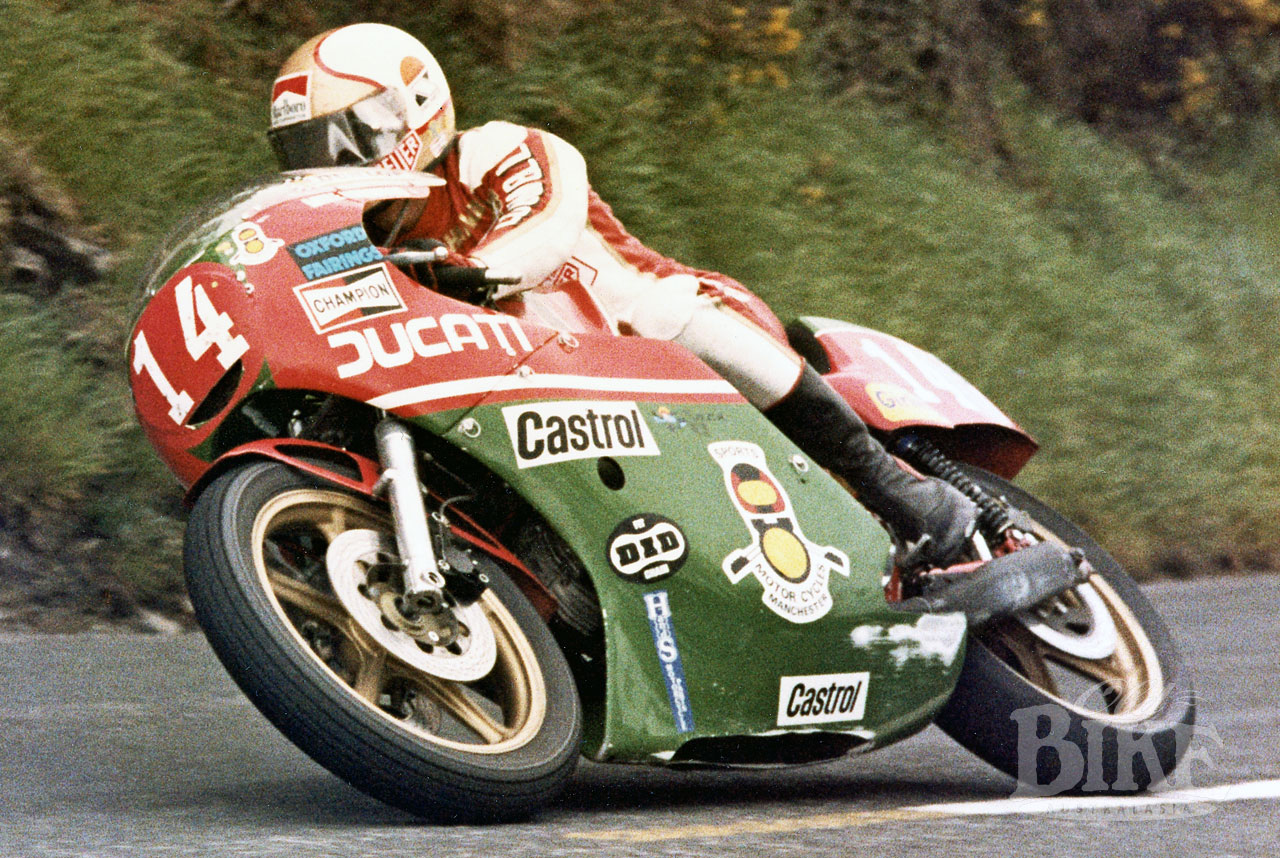

It would have been a perfectly logical move, following Mike Hailwood’s fairy tale win in the 1978 Isle of Man Formula One TT, for Ducati to immediately market a road-going replica of Mike’s mount, in its red and green Castrol livery. But there was little logical about Ducati at the time; now government-controlled as part of the Ente Finanzaria per gli Industrie Metalmeccaniche (EFIM) and reliant on the accountants in Rome to approve the finance for anything and everything.

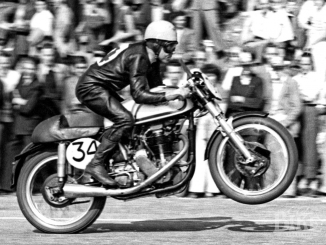

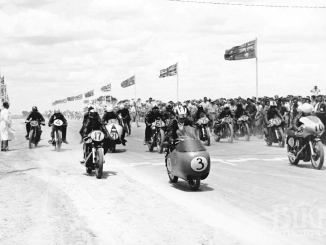

Racing, officially at least, was out, although a degree of participation in selected rounds of the World Endurance Championship was tolerated, with the 860cc 900SS as the basic platform, albeit in much modified form. To keep the exercise at arm’s length from those controlling the purse strings, N.C.R. (Nepoti, Caracchi and Rizzi, and after Rizzi’s departure, Racing) officially developed the race bikes using engine components supplied by the factory, in lighter and higher quality frames, with other proprietary items. The fact that Ducati and NCR were both coincidentally domiciled in Borgo Panigale, 10km from the centre of Bologna, further simplified relations.

Apart from the TT, there were other successes in 1978, including a class win in the Le Mans 24 Hour Race, but there was no attempt to capitalise with a road replica. Indeed, 1979 saw Ducati production shrink to around 3,500 units, the majority being versions of the bevel-drive 900 – the 900SS, 900 GTS and the Darmah. Meanwhile, over in England, plans were being laid for a return to the TT, again with Hailwood in the saddle of a Ducati for the TTF1 race, and hopefully, on a 950cc version for the Unlimited TT. What transpired has been the subject of conjecture and controversy ever since. Pat Slinn, at the time General Manager and Racing Manager at Sports Motorcycles in Manchester, the entrant and driving force for Hailwood’s 1978 TT return, has documented what he considers to be the real story, text from which is reproduced here with his permission.

One tough TT

“One of my first tasks when I joined Sports Motorcycles was to contact Ducati to establish exactly what was happening regarding the F1 machine that was being built for Mike. Steve Wynne (Sports Motorcycles owner) and I really could not get any sensible information from Ducati, and my telexes were being ignored. During a visit to the Ducati factory, I was told that the bike that was being developed and built for Mike was to be based on a number of bikes that were being built by the Ducati factory, and N.C.R. to compete in the 1979 World Endurance Championship. The two engines that were being prepared for Mike would have to be based on the current Ducati square-type of crankcase, and would utilize the standard type clutch. The narrow sand-cast crankcases that were used on the 1978 engine had now been outlawed by the FIM. Franco Farne told me that the power output for the 1979 engine was better than the 1978 engine. I asked if I could see a bike, I was told that all the bikes were being built at the N.C.R. workshops, and all the components were being manufactured, and there was nothing for me to see. Franco Valentini told me after that a separate budget for Mike Hailwood’s machine was not possible due to restrictions being imposed on Ducati’s racing activities by EFIM, and Hailwood’s machine would have to be financed from the endurance racing budget.

“During early May (maybe late April) 1979 I received an invitation from Ducati to attend the official press launch at the Misano circuit in Italy of their 1979 machine and riders that were to compete in that year’s World Endurance Championship. I was told that Mike’s bike was ready for him to test, and would be at Misano. We picked Mike up from Milan Linate airport and drove down to Bologna. At Misano, to say we were surprised was an understatement; there standing in front of us was the F1 Ducati machine that Ducati had built for Mike to defend his Isle Of Man F1 TT and world title on, complete with front headlight, rear light, rear brake light switch, wiring harness and various handlebar switches! There was also a modified 950cc Endurance machine there that (Ducati hoped) Mike might agree to race in the Classic (Unlimited) TT. Mike could not believe it, neither could I nor the representatives from our sponsors who had travelled down to Misano. On closer inspection of the machine I realized that the gear change sequence was opposite to what Mike needed, it had been set up as one down and four up, Ducati knew only too well that Mike had asked for one up four down.

“By the time that Mike was ready to test his bike a lot of television people had gathered to watch and film him. Mike circulated for about ten laps, he then pitted for Dunlop to check the tyres, and for Ducati and N.C.R. engineers to check the bike. During the brief stop Mike had told me that the bike did not steer very well, and it seemed to wallow around on the bumps. He also commented the gearbox sequence was causing him a problem and that he found a neutral once or twice, also he said the engine did not seem very powerful. Mike circulated for about another ten laps then after changing from third to forth after a fast left hand corner he found a false neutral. His instinct took over and he pressed down on the gear pedal instead of going into a higher gear he had changed down into second gear, this caused the rear wheel to slide, however the rear tyre gripped and he was thrown over the high side.

When Mike was brought back to the paddock area I accompanied him to the circuit doctor. After examining him the doctor had suspected that Mike had broken one or two ribs, and possibly a bone in his right arm, and wanted him to go to the local hospital for some X-rays. Mike however decided that the doctor should strap him up and he would leave for the airport to catch a flight back to London, where he was diagnosed with three broken ribs and a very badly bruised arm.

“When they arrived in Manchester with Mike’s bike it did not appear to have changed much from when I had last seen it in Italy. The exhaust system was still scared from Mike’s accident, but it had been repainted and a new fairing had been fitted. The lighting components had been removed and a plastic plate had been riveted over what used to be the headlight aperture. Crucially the gearbox had been converted on the Formula One machine and on the Classic machine to the way Mike needed it.

“After Mike had completed just one lap of practice of the TT circuit, he pulled in and told Steve and I that it did not handle, in fact his words were something like ‘it’s bloody diabolical!’ He also commented on the lack of power from the engine. That evening Farne, Nero and Caracchi worked late into the night. They stripped and rebuilt the front Marzzochi forks and checked the wheel alignment. At that evening’s practice we were more optimistic because Mike went straight past the pits for a second lap, but news soon got back to us that he had stopped on the mountain section of the course with mechanical problems. After we had got the bike back to the workshop, Farne went straight to the front cylinder exhaust valve, it was soon clear that the exhaust rocker had broken. All the pleas that Farne and Caracchi made that this was an unknown problem, and not one seen before fell onto deaf ears, especially when Steve and I realised that Farne had brought some rockers with him in his hand luggage. The new rockers were fitted and more alignment checks made to the bike, Mike went out and completed two practice laps the following morning, however the handling problems were still there. Before that evening’s practice was over Steve had phoned Ray Elliott – a director of UK Ducati importer Coburn & Hughes – and asked if he could send Roger Nicholls’ 1978 F1 Ducati across to the IOM immediately. Roger’s bike was identical to Mike’s 1978 winning machine and it had been masquerading as Mike’s winning bike in Coburn and Hughes’ showroom in Luton.

“Somebody had come up with the idea of putting the 1979 engine into the 1978 rolling chassis. Desperate situations need a desperate solution. Franco Farne to his credit, agreed straight away without even talking to the factory back at Bologna. The bike arrived about midday on the Thursday of practice week. The engine was fitted into the frame and all the ancillary bits and pieces that needed modifying to fit the new frame were modified. Front forks were stripped and checked, what could be used from the current bike was used. The new 1979 exhaust system was a high level one and was tucked behind the frame and would not fit the 1978 chassis, so the old 1978 system had to be quite heavily modified to fit. Dunlop were on hand to fit new tyres, and the Lockheed engineer either modified original brake hoses or made up new ones. I think that the bike was finished at about four o’clock on the Friday morning. It was fired up outside the garage, much I imagine to the surprise of the people staying in the surrounding hotels. Mike tested the bike in the morning’s early practice, and after a couple of laps, in which he had lapped faster than any time on the original bike, he said that the handling was a great improvement, however the power of the engine was way down on the 1978 engine.

“Mike did just one practice lap on the bike on Friday evening to bed in new brake pads, chain and tyres. We were all more optimistic and positive than we had been for the whole of practice week. The history books record that Mike Hailwood finished fifth in the 1979 Formula One TT. During the sixth and final lap Mike’s Ducati cut out close to the finishing line and he coasted to a stop. The battery tray that was welded to the frame had broken loose and the battery was hanging by one wire, Mike quickly reconnected the other wire to the battery, jammed the battery back onto the bike, he managed to fire the bike back up and ride to the finish. Both machines were returned to their original specification. Roger Nicholls’ machine was returned to the showroom of Coburn & Hughes in Luton and again pretended to be Hailwood’s 1978 F1 TT winning bike. After Coburn & Hughes ceased to be the Ducati importers the Nicholls/Hailwood bike was sold to a German motorcycle trader and retailer and displayed in their showrooms in Hanover, Germany.

“Mike had earlier refused, after doing one practice lap, to ride the 950 bike in Friday afternoon’s Classic TT. The 950 Ducati was ridden in the Classic race by George Fogarty, however George crashed at Signpost corner and the machine was extensively damaged. The remains of the 950 were taken back to Bologna in the N.C.R. transporter. N.C.R. repaired this machine and it was sold to Gonzo from Collezione Giappone in Tokyo, Japan. The original 1979 Formula One frame was given to Ron Williams of Maxton Engineering. Ron was asked to modify the frame in any way he thought necessary to make the machine handle and steer. The machine was rebuilt and Steve Wynne continued to race it. George Fogarty raced it at the 1982 F1 TT and crashed on it at the bottom of Bray Hill. The machine caught fire and was badly damaged. I lost contact with this machine after Sports Motorcycles Ltd went into receivership during August 1982. The machine was acquired by the Barber Motorsports Museum in Birmingham, Alabama during 1984 and is displayed in their museum as the actual machine that Mike Hailwood raced to fifth place in the 1979 Isle of Man Formula 1 TT.”

One for the road

Ironically, and after all the privations and subterfuge of the 1979 F1 TT, the vaunted Mike Hailwood Replica finally made its public bow at the London Motorcycle Show in August 1979. As prolific author and Ducati marque specialist Ian Falloon noted, “It was very much a cosmetic adaptation of the 900 Super Sport. Despite its flaws the Mike Hailwood Replica was destined to become Ducati’s most popular model in the early 1980s, lasting beyond the demise of the Super Sport.”

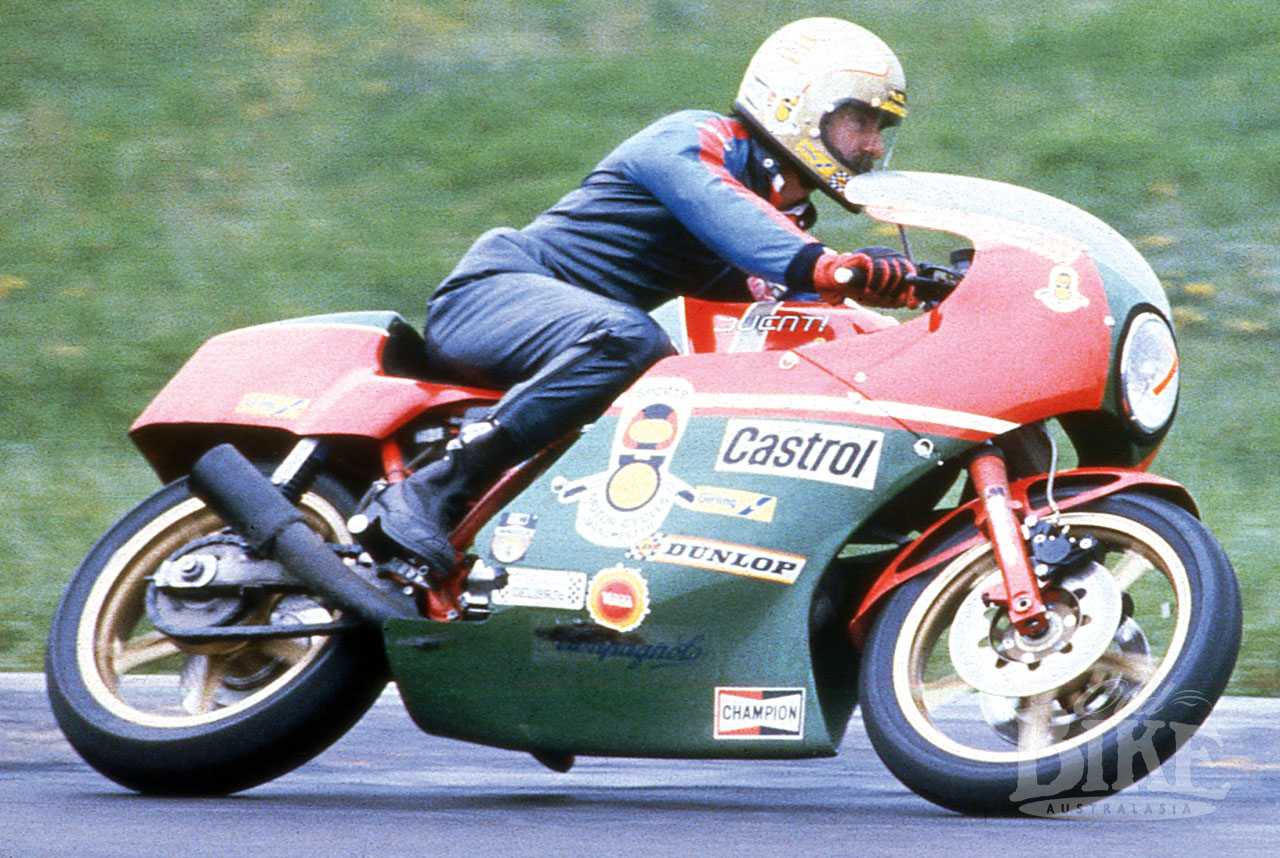

Over the course of several highly acclaimed books, Falloon has chronicled the detail changes to the MHR. Originally, the 1979 model was sold only in Britain and fitted with a one-piece fairing, which was somewhat of a chore to remove for even minor maintenance such as oil changes. “The claimed power for the 900 Replica was 80hp at 7,000 rpm with 40mm carburettors and Conti mufflers. Only Dell’Orto PHM 40A carburettors were fitted to the early 900 Replica. These were without chokes or air cleaners and came with the usual plastic bellmouths. Often the bellmouths had wire gauze filters but these became aluminium in 1980. The red-painted Verlicchi frame was the same as that of the Super Sport. It was mainly the bodywork that set the 900 Replica apart from the Super Sport. As fibreglass fuel tanks were banned in England, the first 200 examples came with a rudimentary fibreglass cover (replicating the NCR tank shape), over the regular 900SS, black-painted, 18-litre steel fuel tank. A solo seat was standard, and converting to a dual seat required substituting a replacement seat pad. To improve ground clearance the Marzocchi shock absorbers were 20mm longer, at 330mm. All Replicas were fitted with cast alloy wheels, either Speedline or Campagnolo on the first series. The wheels and 280mm drilled brake discs were identical to those on the 1979 900 Super Sport. Also shared were the Brembo ‘Goldline’ brake calipers.”

After the initial total of 300 bikes in 1979, 447 more were made in 1980 prior to the introduction of the second series production of 200, which had a steel 24 litre fuel tank, a different dual seat that could be converted to a single seat, and either polished aluminium FPS or Campagnolo wheels. A revised MHR was displayed at the Bologna Show in November 1980, featuring some internal mods (shared with the 900SS) such as different rockers and clutch housing, and a choice of Conti or Silentium mufflers. The Dell’Orto PHM 40B carbs now had chokes fitted and either open bell mouths or air filters. Gold-painted FPS wheels were standard, and the fairing was now a two-piece affair with the two sections secured by Dzus fasteners. Production run for the 1981 year was officially 1,500 units. Minor updates graced the 1982 model, with slightly longer Marzocchi forks but with reduced travel front and rear. By 1983 the Pantah, with its belt-driven overhead camshafts, was seen as the way of the future for Ducati, but the MHR and other 900 models continued with the bevel system. The engine was still kick-start, with around 800 produced.

The 1984 production year marked the beginning of a new regime for Ducati with the tie-up with Cagiva taking effect, whereby Ducati would become responsible only for engines. As a result, motorcycle production dropped considerably, and the new electric-start motors, with spin-on oil filters were gradually introduced. Now based on the 900 S2 model rather than the SS, most of the 1984 MHR production featured push-button starting. A new narrower and slightly taller fairing was fitted, now split horizontally with the red top section and bottom green section separated by a white stripe. The gold-painted wheels were now made by Oscam and the brake calipers moved to behind the fork legs.

There had been considerable doubt whether the Ducati name would even grace motorcycles beyond the end of 1984, but when the Cagiva takeover was complete, it was decided to retain the brand, and to continue with a reduced production of complete machines. Nevertheless, it was a time of change and some confusion, as the new Mille engine gradually came on stream, but it took a sharp eye to pick the difference on the MHR, which was identified mainly by a small ‘Mille’ scroll on each side of the fairing. With a revised bore and stroke of 88mm x 78mm to achieve 973cc, Nikasil-plated barrels and a one-piece nitride crankshaft, dry hydraulically-operated clutch plus the electric starter, the Mille engine was an overdue step. The Mike Hailwood Replica finally ceased production early in 1986, the last run of 250 bikes bringing the total to approximately 6,000.

Today, the MHR is a highly desirable motorcycle with a cult following worldwide. It may have been basically a dressed up 900S but as the French say, “Viva la difference”.

One from the class of ’79

Michael Arnott’s 1979 MH Replica bears chassis number DM860SS 900115, identifying it as one the rare 1979 survivors. This has the steel tank replicating the TT bikes, with the two-piece single seat and the unloved but extremely rare one-piece fairing. As Michael says, “It came to Australia from New Zealand, where it was about to be auctioned. I agreed to pay the reserve price and had it shipped over. It’s not concours but it is original, even things like the Perspex screen is the one it came with, as is the seat, wheels, shocks, brakes and so on.” Michael had the bike detailed by Michael Mifsud, who described the pitfalls of removing the fairing, which sounds like a typically Italian piece of impracticality. “I found the best way was to put a sling around the top steering crown, then haul it up with a hoist to get the front wheel off the ground. Then I pulled the front wheel out, removed the mudguard, and was able to drop the fairing down the forks and slip it out. It’s quite a job.”

As Queen Elizabeth II said, “Grief is the price we pay for love.”

Specifications: 1982 Ducati MH Replica

Engine: SOHC 90º V-twin with Desmodromic valve operation. 2 valves per cylinder.

Bore x stroke: 86mm x 74.4mm

Capacity: 863.9cc

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Ignition: Bosch BTZ Electronic Inductive Discharge

Starting: Kick.

Transmission: 5 speed, gear primary drive, chain final drive. Wet clutch.

Frame: Tubular steel double cradle.

Suspension: Front: Marzocchi telescopic forks 38mm stanchions.

Rear: Swinging arm with 2-way damped hydraulic shock absorbers, 5-way spring pre-load.

Wheels/tyres: Cast alloy with 100/90 V18 front and 110/90 V18 rear tyres.

Wheelbase: 1500mm

Dry weight: 202kg

Fuel capacity: 24 litres

Max speed: 220 km/h.