For a brief time in the ‘sixties, a nippy 175 twin gave plenty of 250s a hurry up.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

There’s an old saying; it’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog. This could have been coined for the Bridgestone DT175, because if ever a motorcycle punched above its weight, this is it.

The little twins were the logical extension to the range of robust and spirited single cylinder models which ranged from 50cc to 100cc. The Bridgestone 90 was a strong seller and a stronger performer – accounting for a major slice of Bridgestone’s ever-increasing sales. The company produced 240,000 motorcycles (and more than 350,000 bicycles) in 1965 from its plant in Ageo, a statistic not lost on its competitors, whose collective grumbling eventually led to an entente cordiale that saw Bridgestone cease motorcycle manufacture in return for a guaranteed original equipment tyre supply to Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki.

Bridgestone motorcycles arrived in Australia in mid-1966, distributed by the large American company McCulloch, whose main business was chain saws, outboard motors and go-kart engines. McCulloch had secured the US West Coast distribution for Bridgestone in the US in 1965, while the distribution in the rest of the country was handled by Rockford. McCulloch set up a subsidiary, McCulloch of Australia, in 1966 to import and distribute the Bridgestone range of 50 and 90cc singles, both in road and ‘trail’ versions, with a race-kitted ‘Scrambler’ version of the 90 also offered at $319.00, plus the 175 DT (Dual Twin), priced at $498.00. McCulloch quickly appointed Frank Mussett and Burrows & Stacker as dealers in Victoria, while sidecar racer Stan Bayliss was given the rights to southern Sydney.

The Tokyo Motor Show of 1965 was where the 175 DT first appeared. It was effectively a doubled-up 90, sharing the same 50mm x 45mm bore and stroke, but more than doubling the power output – 7.8 horsepower at 7,000 rpm for the 90 versus 20 horsepower at 8,000 rpm for the twin. With the comparative weights of 82kg to 123 kg, the 175 had a very competitive power-to-weight ratio. Acceleration was remarkable for a 175: the standing quarter mile covered in 17 seconds with a top speed of 113 km/h.

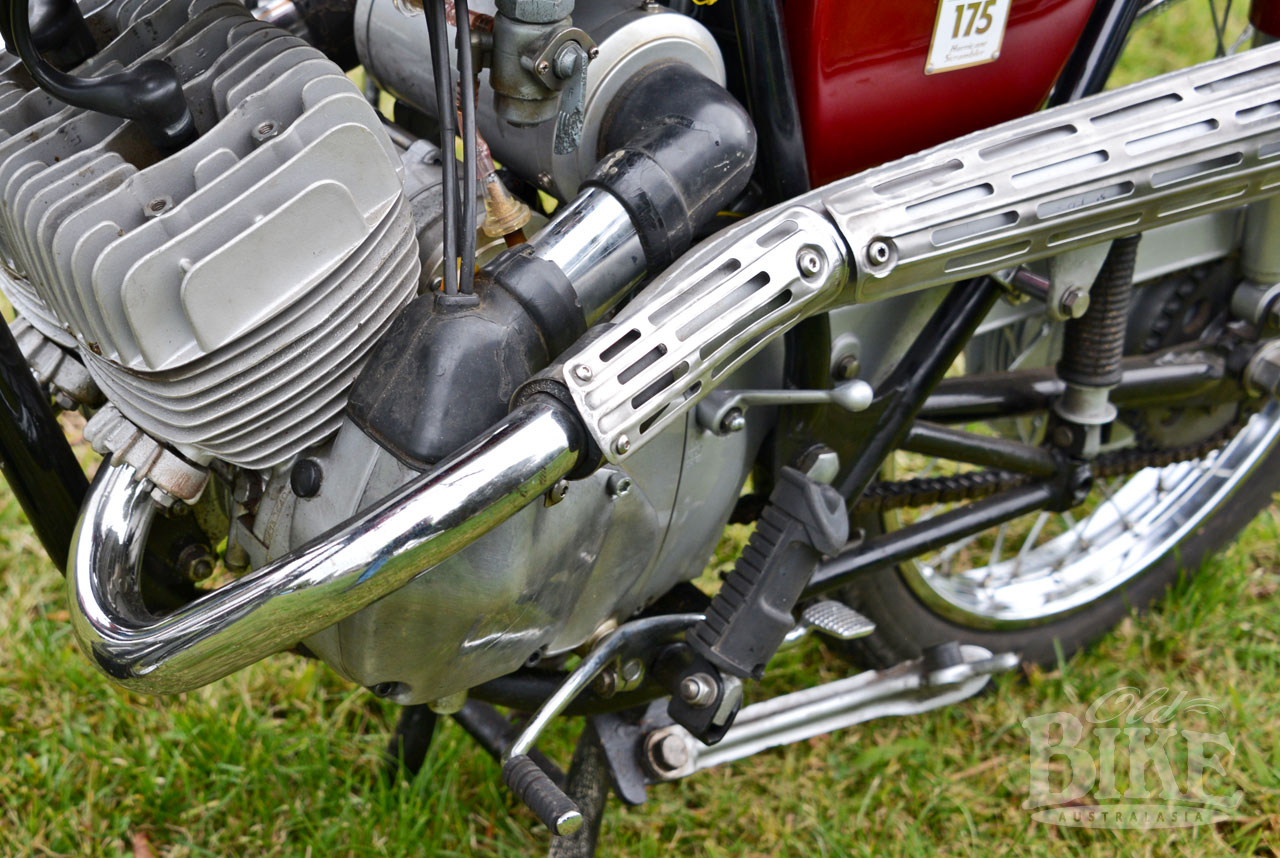

Like all the Bridgestone lightweights, the DT used rotary valve crankcase induction, which although efficient and effective, resulted in a fairly wide motor with carburettors at each end of the crankshaft. The concept of rotary crankcase valves for two strokes had been admirably demonstrated on the East German MZ racers, and copied by several others. Rotary valves eliminated the old bugbear of piston-port engines; that of enforced symmetrical port timing between the intake port opening and closing. Rotary valves, at least in theory, permitted unlimited variation in port timing, and a wider spread of power. On the 175 DT, the Amal-pattern carbs were enclosed in their own neat polished alloy covers, which kept dust and water out and kept the engine nice and clean and free from the usual two-stroke petrol/oil mess. The carbs breathed through tubes connected to a barrel-shaped air filter which sat in the position normally occupied by carburettors at the rear of the engine above the gearbox. Of course, having both crankshaft extremities taken up with carburettors, a different location needed to be found for the generator and ignition. These two components were combined into a one-piece unit, located beneath the air filter and driven by a coupling from the clutch-hub gear.

Cylinder bores were chrome-plated directly onto the alloy castings – a method claimed to give more even expansion rates and hence, less chance of seizures. On the 175 DT, Bridgestone addressed the often tricky problem of accurately timing the ignition by putting two locating holes in the left side flywheel, 180º apart, where a pin could be inserted through a hole in the crankcase. This indexed the crank with one piston stopped at 21º before top dead centre, where the point were set to break. Then the pin was removed and the crank turned 180º and re-indexed so that the other set of point could be set.

Another worthwhile feature was the automatic oil pump (dubbed Jet Lube Oil Injection by Bridgestone), driven from the left side of the crankshaft, featuring a variable output according to throttle opening. The pump sat behind the left side carburettor with a cable connecting it to the twist grip. Orifices in the carburettor mounting stubs, ahead of the rotary discs, delivered the oil to the engine. The oil supply came from a conventionally mounted tank on the right side, complete with a small window for checking the level. Even with this system, Bridgestone recommended mixing a small amount of oil with the petrol during the running-in period.

A quirky feature was the gearbox, which could be used as either a four or five speeder. This feature was activated via a lever (called the ‘Sport Shift’) located on the left side of the engine casing near the countershaft sprocket. In the rearward position, this lever engaged the four speed mode, the gearbox operated in ‘rotary’ fashion, meaning that in top (fourth) gear, the change pedal was pressed down again once for neutral, and once more to engage first gear. This may have been handy when in traffic and pulling up for traffic lights, but it caused more than the odd over-rev if the rider forgot which pattern had been selected. Reversing the direction of the lever engaged a conventional five-speed transmission, with fifth gear as an overdrive, and with the neutral in the normal position between first and second gears. A heel-and-toe pedal was used and folding footrests were an unusual feature for the time. It’s debatable whether anyone actually bothered with the four-speed rotary option. One handy feature (especially if one stalled the engine in traffic), was the kick starter that worked on the primary gears, meaning the bike could be started in gear when the clutch was engaged.

Bridgestone made much of its all-welded tubular steel frame in the advertising for the 175 DT, and road tests of the day praised the overall handling, even though most found the springing too soft. There was no adjustment provided for either the front forks or the rear shock absorbers. Stopping duties were performed by a very neat 180mm (7 inch) twin-leading shoe job at the front, with a single-leading shoe drum of the same size at the rear.

Styling was typically conservative, like the smaller models, and available only in Candy Red, but with plenty of chrome and polished alloy. According to the factory manual, “The balanced appearance of the motorcycle and fine finish of all parts combine to fascinate the rider so he wants to get on it and take a ride as soon as he sees this motorcycle”. So there.

Instrumentation consists of a speedo mounted in the headlamp, with a neutral light and high beam indicator. That’s it – no tacho, although it certainly would have been handy on such a free-revving engine. A large steering damper knob sits atop the steering stem.

If there’s one feature that dominates the 175 DT it’s the mufflers; formidable affairs that connect to the header pipes via rubber sleeves held in place by spring clips. Over time, these rubbers harden due to the heat, resulting in less than perfect sealing. And it’s the mufflers, more than any other feature, that distinguish the DT from its stablemate, the Hurricane Scrambler (175 HS). These enormous items almost require the rider to have cowboy-style bow legs, such is the width of the bike at calf height. Adding to the overall dimensions are substantial (and necessary) heat shields, and rather than the megaphone-style ends of the DT mufflers, those of the Hurricane finish in rather menacing looking ‘stinger’ pipes. The high pipes of course mean that the lower run of the rear chain is exposed to the world.

Other distinguishing features of the Hurricane are the high-rise and braced handlebars (requiring longer front brake, throttle and clutch cable than the DT), a skid-plate under the engine, and the abbreviated front mudguard. Mechanically, the two models are identical. There was even a third 175 model, albeit US-only, called the 175+Racer, which the maker described as “A factory-tuned, limited production model designed to give the dealer a successful promotional program through racing. Features include dual carburation, modified dual rotary valves, hand-polished ports, and other performance modifications. Virtually unbeatable in the hands of an experienced competition rider.” Ah, the days of truth in advertising!

With no local 175 racing class, very few Bridgestone DTs made it onto the track in Australia, but one notable exception was the Bayliss brothers; Stan forsaking his outfit (and his TD-1A Yamaha racer) to gallop the 175 DT in the hotly contested 250 production class at Oran Park. His brother Merv actually thrashed hoards of Suzuki Hustlers and Yamaha DS3s to win one of the events, only to be disqualified as the engine was under-sized for the 200cc – 250cc class!

The nippy 175 was inevitably overshadowed by the rather scary 350 GTR which appeared in 1967, but time was already running out for Bridgestone motorcycles, hastened not only by the threats from the other Japanese brands, but the ever more stringent US emission laws which would eventually spell the end for virtually all two strokes. Before the decision to pull the pin, Bridgestone engineers even drew up a four-cylinder four stroke 350, but it never reached the metal stage.

A pigeon pair

The bikes featured here belong to Ray Kinch (DT) and Laurie Boardman (Hurricane). While Laurie’s is largely original and unrestored, Ray’s was a total basket case as received. Ray is a real fan of the marque; his collection including a 90 Deluxe, a 90 Mountaineer, 90 Sport, and the DT. The poor old 175 was not just dilapidated, but incomplete; missing the air filter and the related hoses, rear mudguard, tool box, correct handlebars and switches, battery box and cover, rear chain guard and many small items. It was more a complete rebuild than a restoration, but the finished job looks a treat and is regularly used in vintage rallies. The chrome plating on the petrol tank of Laurie’s Hurricane was beyond saving, so he opted to replace the chrome panels with silver paint.

1966 Bridgestone 175 DT Specifications

Engine: Twin cylinder two stroke with rotary disc valve induction.

Bore and stroke: 50mm x 45mm = 177cc

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Power: 20 hp @ 8,000 rpm

Torque: 1.9kg-m @ 7,500 rpm

Electric system: AC generator

Ignition system: Battery and coils

Carburation: Amal type VM 17SC

Transmission: Four speed (rotary) or five speed (return)

Maximum speed: 132 km/h

Frame: Tubular cradle, all welded

Front suspension: Telescopic fork

Rear suspension: Swinging arm

Weight: 123 kg

Fuel tank capacity: 18 litres

Wheelbase: 1235mm

Tyres: Front 2.50 x 18, Rear 2.75 x 18