From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 65 – first published in 2017.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Jim Scaysbrook, Alan Cathcart

Draconian emissions laws had all-but killed the road-going two-stroke by the late ‘nineties. But one company believed there was life in the design yet.

Priced at $34,490 in Australia, there was only one motorcycle more expensive in 1997 than the Bimota Vdue, and that was the $35,995 Ducati 916 SPS. Both were high performance vee twins, but that’s where the similarity started and finished. The Vdue was a 500cc v-twin two stroke no less, from a time when ring-dingers had largely been consigned to museums. Only on the Grand Prix circuits did the two-stroke continue to reign, and that was about to change as well. But then, Bimota had always done things differently. It’s just that this time, the result was so catastrophically unsuccessful that it sent the company to the wall.

First, let’s establish just who Bimota is, or was. Back in the late ‘sixties, Massimo Tamburini (yes, the same man who later became synonymous with Ducati, MV Agusta and Cagiva) had a successful business making heating equipment, based at the Adriatic seaside town of Rimini, where many an early-season racing battle had been fought on the streets. Just down the road at Pesaro was the famous Benelli factory. Tamburini was well known in the district for his ability to tinker with motorcycles and produce something that worked much better than the original. As well as tweaking his mates’ bikes, Massimo transformed one of the original, plug-ugly 600cc MV Agusta fours into a sweet handling, decidedly quick and good looking sports machine, which pleased everyone except Count Agusta himself, who had taken great pains to produce a motorcycle that was diametrically opposed to the factory’s legendary racers. The last thing the Count wanted was for boy racers to fiddle with the road bike and dilute the factory’s racing reputation, which was the prime reason the 600cc capacity was selected. But Tamburini managed to circumvent all that, turning out a motorcycle that was scarcely recognisable compared to the original and which featured a frame of his own design.

Replicas of that frame were soon produced in very limited numbers, one fitted with a CB750 Honda engine and raced by Luigi Anelli. Such was the interest generated, a company was soon set up to capitalise on the market for similar machines, and the name was coined from the first two letters of the surnames of the three partners – Valerio Bianchi, Guiseppe Morri and Tamburini. Initially, Bimota’s limited production focussed on chassis kits for road-going replicas of Anelli’s race bike, designed to accept the customer’s CB750 engine and dubbed the HB1. The kits used an eclectic range of proprietary equipment such as Marzocchi rear shocks, Ceriani forks and Scarab disc brakes, with Bimota’s chrome-moly frame with its box section swinging arm. Tamburini continued to concentrate on race bikes, initially to take the ubiquitous Yamaha TD2 and TR2 engines; in fact the road bike sales were primarily seen as a necessity to finance the racing side, which was always the firm’s priority. There were other race chassis too, notably a batch of 50 Suzuki TR500-engined machines commissioned by Suzuki’s Italian importers, as well as chassis for Paton four stroke and two stroke twins and fours, and Harley-Davidson 500cc two stroke twins. In 1980, South African Jon Ekerold took out the 350cc World championship riding a Bimota chassis with a Yamaha TZ350 engine.

As well as the racers, a continuous supply of exotic road bikes flowed from the Rimini factory, with Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki power, but these were relatively conventional motorcycles compared to what lay in store. The Tesi, with its hydraulically operated central hub steering, caused a sensation when it first appeared at the Milan Show, but it did not translate into volume sales, mainly because Bimota did not have the finance to back the production. In July 1984 Bimota was declared insolvent, and placed into administration. Under Italian law, the company was given two years grace to permit restructuring and to trade itself out of debt. Mainly due to the sales success of the Ducati Pantah-engined DB1, Bimota did indeed turn its fortunes around, and was able to be released from administration in July 1986. By this stage Tamburini was gone, replaced by the DB1’s designer, Fredrico Martini. The Yamaha FJ1200-powered YB5 and the FZ750-powered YB4 also helped fill the coffers, sufficient for a tilt at the inaugural Superbike World Championship in 1988. Riding a fuel-injected YB4, Davide Tardozzi was runner up to Honda rider Fred Merkel.

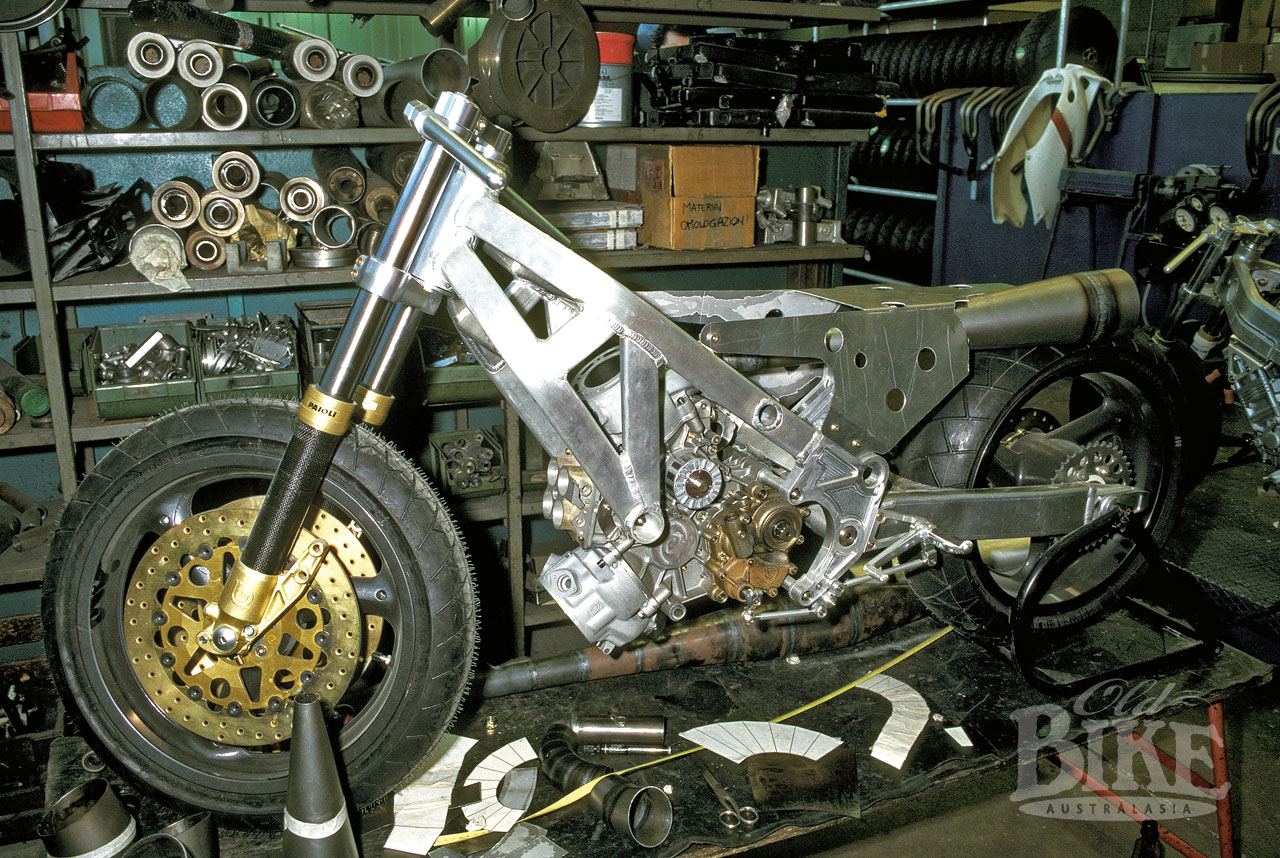

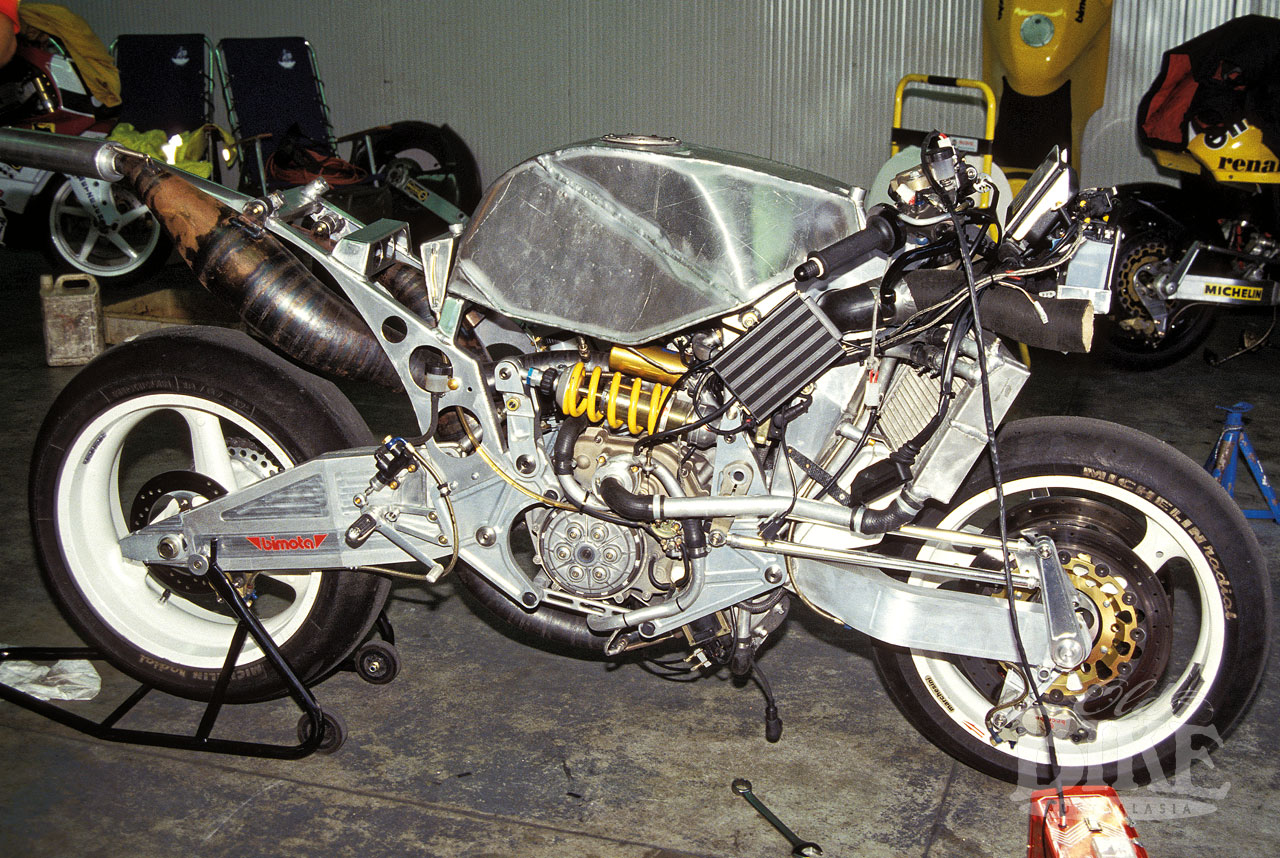

Rather than steer a conservative ship in the face of the delicate financial situation, Bimota chose to build its own engine for the 500cc GP class which was then the domain of four-cylinder two strokes which had a minimum weight of 130kg. It was a v-twin two stroke which initially used a Tesi-style front end, but strictly speaking, Bimota did not actually build the engine, which was outsourced to the nearby Franco Morini Motori. The FIM had recently gazetted a lower (105kg) limit for 500cc class twins, the aim being to encourage production of cheaper machines that privateers could afford to buy and race, and Bimota aimed to exploit that advantage. The fuel-injected engine used forced lubrication for the twin crank bottom end and poked out 132 hp. Parallel to the racing effort, Bimota was also working on a road-going version of the 500, but it was a long time coming. This was the Vdue, which first appeared in prototype form in 1992 but took a full five years to reach the stage of production. During this period, various mock-ups of the Vdue (without the hub-centre front end) did the rounds of the Expos, to the point that few believed it would ever reach the production stage. But eventually, and against all conventional wisdom, it did. Sadly, the sole remaining company founder Morri had been forced out in the face of dwindling sales, his place taken by Walter Martini.

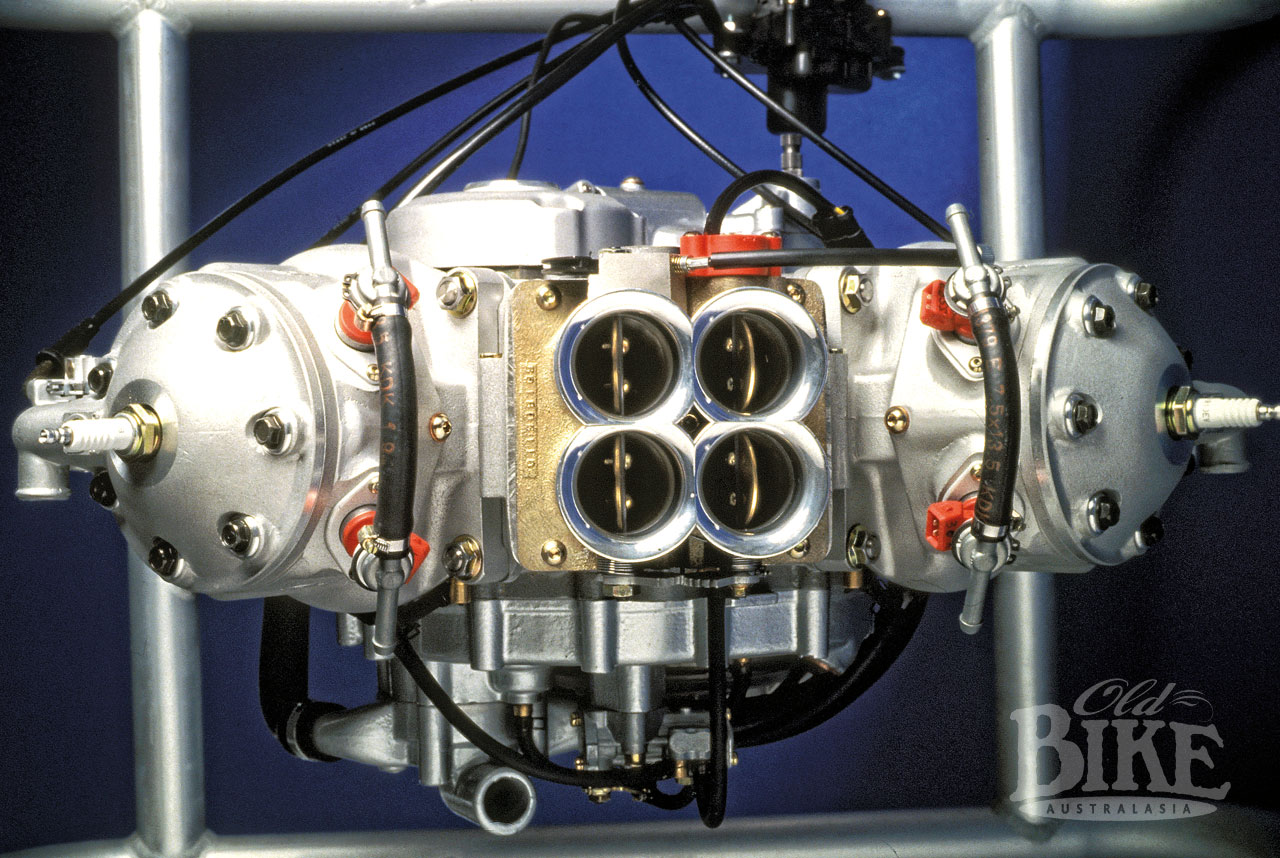

The Vdue was touted as a GP racer for the road, and in most respects, it was. At the heart of the matter was the combination of electronic ignition with direct, electronically monitored fuel injection, which was absolutely critical to the model meeting the ever more stringent emissions laws in Europe and USA. Honda had tried a similar set up on its GP two strokes and abandoned it, but Bimota reckoned it could be made to work. The two-stroke’s bete noir, in carburettor form, was that fuel still made its way into the engine when the throttle was shut, and also arrives inside while the exhaust port is still open. The escape of this unburned mixture was pure death as far as exhaust emissions went. With DFI, the fuel flow stopped when the throttle was closed. The Vdue design took air into the crankcase via reed valve blocks located within the cylinder vee, with fuel added into the transfer ports via the injectors when the exhaust port had virtually closed. It was this need to detonate the mixture as late as possible (in the interests of lower emissions) that had led to the demise of the two stroke in road-going form, as there was simply insufficient time for the air/fuel mixture to remain in the combustion chamber before being expelled. In the case of the Vdue, fuel was sprayed from the injector directly onto the top of the piston fractionally ahead of the spark, theoretically allowing sufficient time for the mixture to atomise before being ignited. Each aspect of this process was measured by the computer system, which monitored the oxygen levels in the air box and exhaust and also constantly checked temperatures of air, water and exhaust gases. Bimota’s EFI was expensive to develop, but the company had planned to recoup some of the cost of their patented system by licencing the technology to other manufacturers of two strokes. Bimota’s system used twin 40mm throttle bodies for each cylinder, with fuel supplied by an electric pump.

There was no pre-mixed fuel required (with its inherent contribution to the emissions) because the Vdue used forced bottom end lubrication, four stroke style, sharing the oil with the gearbox. A separate pump sent oil from a tank within the fuel tank to the big and little end bearings, while the Nikasil bores and pistons were lubricated via orifices in each cylinder. Some oil was still burned and sent out the exhaust pipe in the form of smoke, but Bimota claimed this was less than half of that on a conventional two stroke.

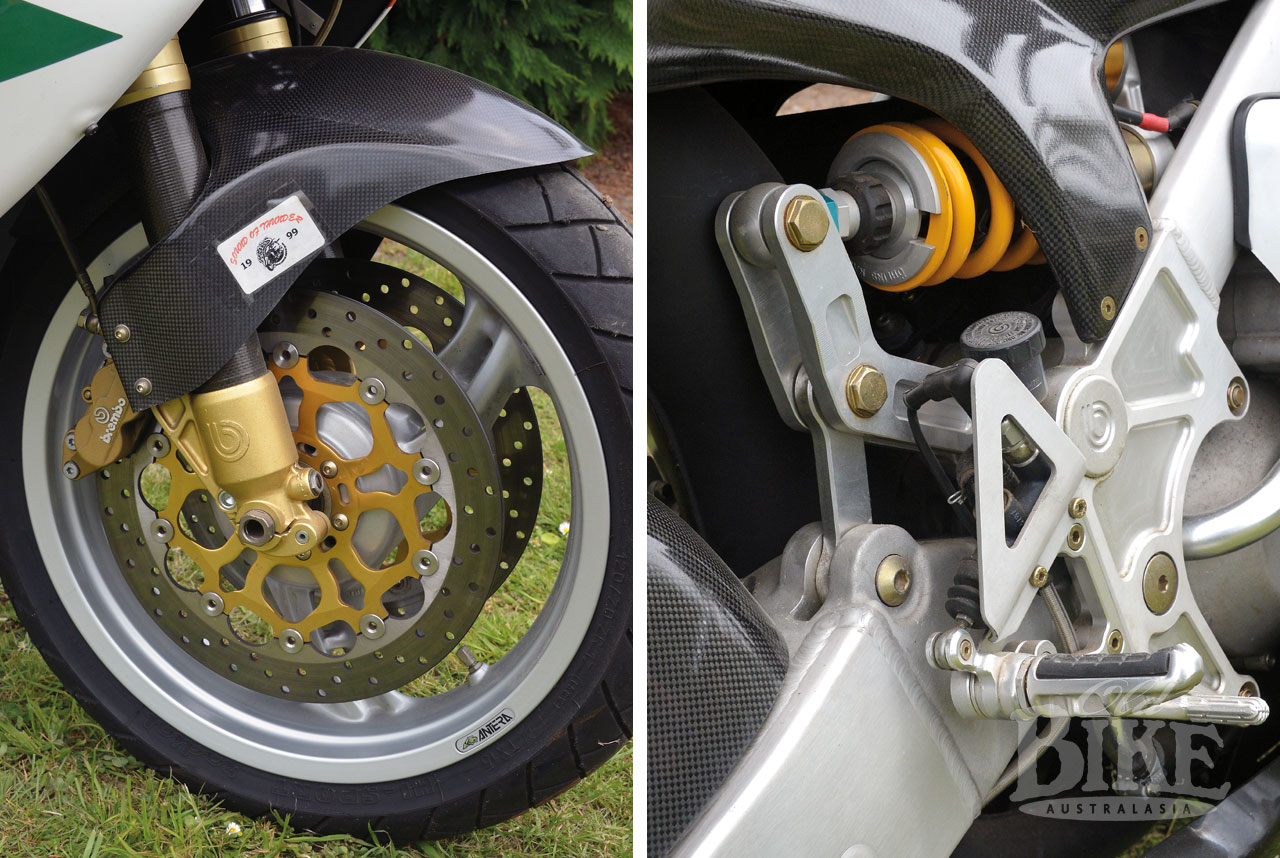

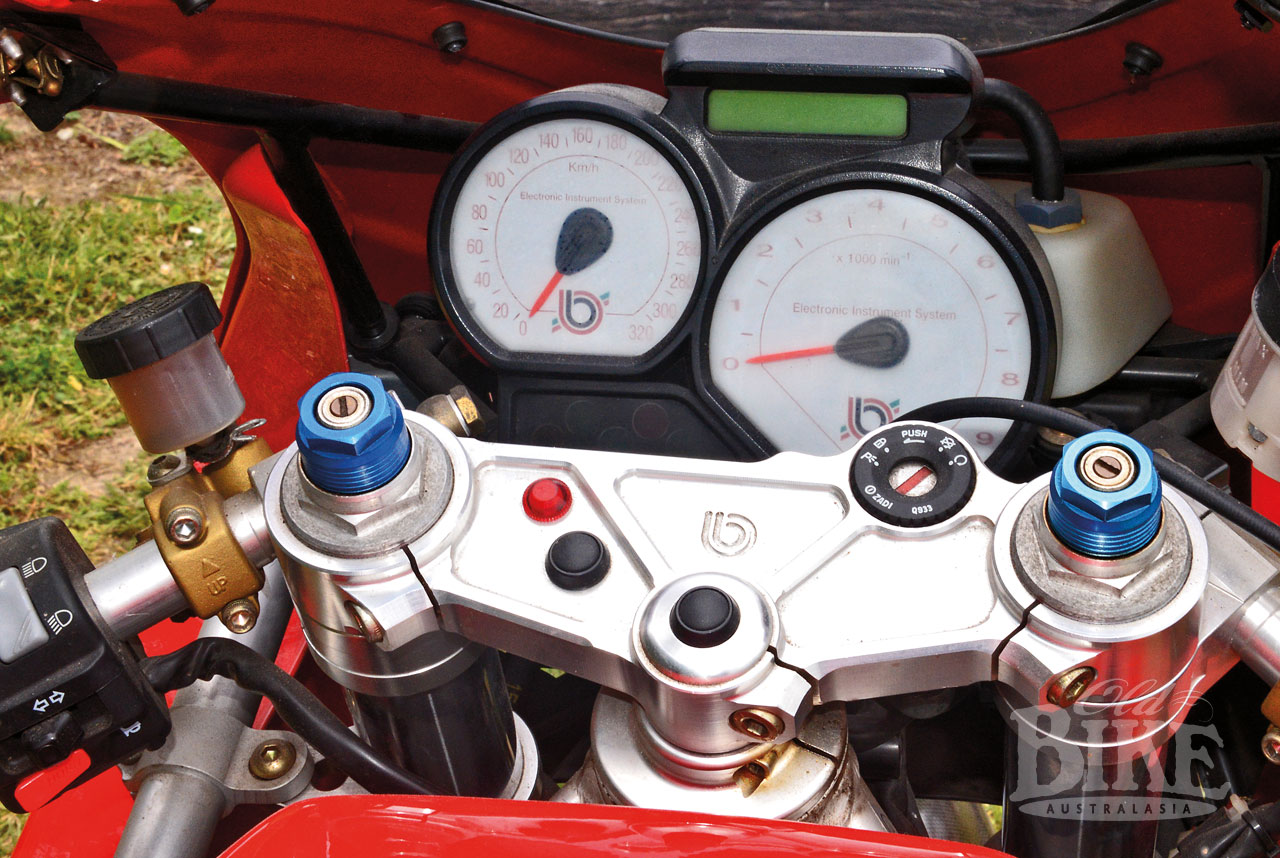

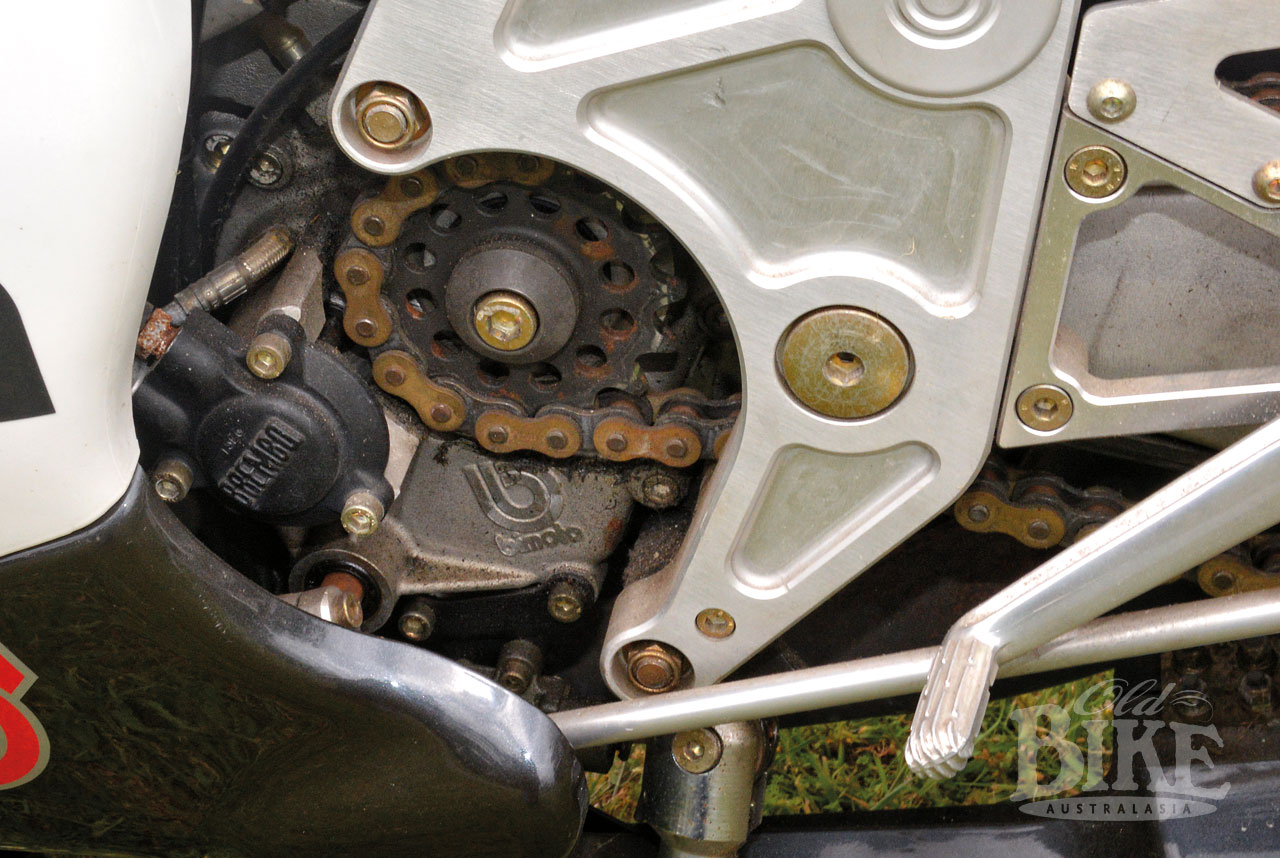

The Vdue was designed by Piero Caronni, and although it looked the goods, and the company had a healthy order book with very patient customers, there were problems aplenty from the very start. There were so many problems that it is impossible to pinpoint any one as being the cause for the malaise that engulfed the model. But before we get into the troubled and very brief history of the Vdue, it’s worth looking at the specification. The engine was a 90º v-twin with twin contra-rotating cranks geared together, a bore and stroke of 72 x 61.25mm to give 499cc and a power output of 105hp. A six speed, side-loading cassette gearbox with a built-in quick-shifter ran a dry clutch. The frame was made from oval-section aluminium, with an exquisite alloy swinging arm. Because it was originally designed to take the Tesi-style front end, the engine was built to take the loads as a fully stressed chassis member. Up front were 46mm Paoli front forks with 120mm of travel and a single shock rear end moving through 130mm. Standard tyres were 120/70 ZR 17 TX15 35GX Michelin front, and 180/55 ZR 17 TX25 35GY Michelin rear, sitting on Antera three-spoke alloy wheels. Stopping was via Brembo Goldline 4-piston front calipers with twin 320mm floating discs, and a single-piston caliper at the rear on a 230mm disc. Wheelbase was 1340mm and dry weight a svelte 164kg, thanks in part to the use of carbon fibre for the rear fairing, mufflers and other parts. Those mufflers sat on the ends of some very exotic stainless steel expansion chambers made by Bimota themselves.

And so to the long-awaited moment in 1997 when those patient customers began receiving the new motorcycles. The aforementioned fuel-injection system was developed in the hope and expectation that it would allow the Vdue to cope with the ever more stringent emission laws, but the power delivery was badly flawed as a result – it was literally all or nothing and just 1500 revs wide. In traffic, the engine hunted annoyingly until it reached, and stayed briefly within, the power band, which kicked in around 7,000 rpm. The rancour was instant and loud, owners complaining vehemently that they expected a lot more for their money – like a bike you could actually ride. There were other gripes, in fact lots of other gripes. Oil leaks were commonplace, fuel consumption was horrific and consumption of the highly expensive fully synthetic two stroke oil even more so. Plugs fouled, electrics developed a mind of their own, and there were problems with the cranks. With so much at stake, Bimota had no option but to make good the repairs at their own expense. Bimota tried hard to find a solution to the fuel problems, initially repositioning the injectors deeper into the cylinders, which helped slightly. The only complete solution to the fuel injection malady was a complete back-flip; revert to a pair of Dell’Orto 39mm CV carburettors, which immediately negated the emissions target. This was officially known as the Evoluzione upgrade.

With the factory filling up with abandoned Vdues, Bimota even tried to placate owners by offering them a swap for a SB6R, but most were having none of that. The Vdue would work in race trim, but not on the road, and in desperation Bimota hit upon the idea of a one-model race series, which it figured might just eat up many or most of the stockpiled bikes. It did, to a small extent, with 26 carburettor ‘Trofeo’ (Trophy) models produced (or converted) but there was still the problem of reimbursing furious owners, and this proved insurmountable. In 2001, Bimota was declared bankrupt (again). Ironically, the Vdue designer, Piero Caronni, purchased the complete inventory for the model from the liquidators, and set about working through the issues, which resulted in the Evoluzione 03, 04 and Finale versions; all using carburettors and with the power up to 120 hp on the 03 and 130 hp on the Finale. He was also successful at flogging them to collectors far and wide and still does so. To be fair, the bikes could be converted for track-only use without undue consternation, but only by delicately side-stepping individual country’s registration laws could they be ridden on the road. In fairly recent times, new crankcases have been produced, and this has confirmed that many of the engine’s original problems lay in the original cases, which were flawed in several respects and failed to seal correctly. One reason for this was that there was insufficient space to fit crankcase seals of the appropriate size, and the smaller seals simply could not cope.

Using modern technology, even the EFI has been made to work satisfactorily – a fix that involves replacing the entire injector units with a product capable of more precise mapping – but the fact remains that the engine needs a comprehensive rebuild after about 5,000 km. Still, the Vdue still boasts one of the most impressive power-to-weight ratios of any road-legal motorcycle, ever. What you had was a motorcycle that weighed the same as an Aprilia RS250, with double the horsepower. According to Caronni’s website www.vdue.it 185 of the original EFI models were built, 26 Trofeo models for the one-make series, 141 Evoluzione models (set up for road registration in Italy), 14 Corsa Evoluzione and 22 of the last version, 22 Racing E.F. (Edizione Finale). All except the original 185 were fitted with carburettors.

As for Bimota itself, the company was reborn in 2003 with new management and today produces a range of avant-garde motorcycles that includes the 999cc BB3 with its 4-cylinder BMW engine, the radical Ducati-engined Tesi 3D and the 1198cc desmo DB9. The reborn Bimota range still calls Rimini home, but you won’t find a photo of the Vdue hanging on the factory wall.

Down under Vdues

The featured Vdue belongs to New Zealander Martin Bootten and is number 4 of the original batch, still sporting the direct fuel injection system. Martin believes it is one of around 23 that were not returned to the factory, and following “computer and exhaust changes”, runs perfectly. He obtained a diagnostic kit from a dealer in Norway which plugs into the computer and sorts out most of the issues. He says the complex muffling system required under European laws “strangled” the engine and severely restricted performance and reliability. A second model is resident in a private museum in Nelson. In Australia, a Vdue was an exhibit in the now-closed Australian Motorcycle Museum at Haigslea, Queensland as part of an extensive collection of Bimotas.

Specifications: 1997 Bimota V Due

Engine: V-twin two stroke with twin contra-rotating crankshafts.

Bore x stroke: 72mm x 61.25mm

Capacity: 499cc

Compression ratio: 12.0:1

Ignition/fuel: CDI. Marelli/Bimota electronic fuel injection. 4 x 40mm throttle bodies with twin reed valve blocks.

Transmission: 6 speed, cassette style side loading.

Clutch: Dry multi plate.

Final drive: Chain

Frame: Oval section tubular with engine as fully stressed member.

Suspension: Front: 46mm Paioli telescopic forks. 120mm travel.

Rear: Single Ohlins shock with rising rate linkage. 130mnm travel.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 320mm discs with Brembo 4-piston callipers.

Rear: 1 x 230mm disc with Brembo twin piston calliper.

Weight, dry: 164kg

Seat height: 805mm

Wheelbase: 1340mm

Power: 105ps at 9,300 rpm

Torque: 8.4kg-m at 8850 rpm.

Maximum speed: 240 km/h