From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 62 – first published in 2016.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook/OBA archives.

Before the four stroke invasion took over, Suzuki’s big two stroke twin enjoyed an enviable reputation as a roadster, as well as proving very receptive to tuning for the race track.

When the first version of Suzuki’s big two stroke twin appeared as the 500/Five in 1968, with the vast majority of production destined for the USA, it rapidly gained a reputation for a prodigious thirst, and extremely wayward handling, as well as a rather astonishing turn of speed. That model was fairly short-lived, and was replaced by the T500 Cobra. Outwardly and inwardly there was little difference, but in an attempt to tame the handling, Suzuki lengthened the swinging arm by a whopping 11.7mm. The ploy worked, and thereafter the Cobra gained a reputation for predictable steering to match the impressive power output. The extra length also had a spin-off of providing more space for a pillion passenger and for mounting panniers, so the Cobra began to find favour as a tourer as well as a sports machine. As a concession to British and US markets, a cross-shaft in the gearbox permitted the gear change and brake to swap sides if required. That gearbox, at least initially, had what was supposed to be a safety feature whereby first gear could not be engaged from second while on the move. Because the tachometer drive was from the countershaft, the instrument ceased functioning with the clutch in.

Engine-wise, the T500 dispelled the belief that large capacity two strokes were difficult if not impossible to build, although the legendary twin-cylinder Scotts had put paid to that myth a half century previously. The motor boasted a very hefty bottom end on three ball main bearings, with direct oil injection into the crankcases via Suzuki’s CCI lubrication system. This used throttle-controlled oil metering to the intake passages and the outer main bearings. After passing through the mains, the oil is fed to the caged needle rollers of the big ends. An unsual feature was the oil pump and tachometer drive being taken from the gearbox output shaft, which meant that holding the clutch disengaged with the motor running for too long can starve the engine of oil (and the tacho stopped working). The kickstart connected to the gearbox mainshaft, meaning the engine could not be started in gear with the clutch in, and as the kickstarter is mounted on the left, stalling the bike at an intersection usually involved dismounting to re-start it. A practical touch was the vacuum operated fuel tap, which could be left on without flooding the crankcase.

The Cobra of 1968 poked out 46hp at 7,000 rpm, with 5.5 kg/m (37.5 lb/ft) of torque at 6,000 rpm. It was no lightweight, scaling 185kg ready to roll. Early testers complained of pitiful brakes and the need to carefully chart fuel stations on any route. The styling also failed to please many; with a dumpy fuel tank with out-dated chrome side panels and a velour seat. There was noting particularly special about the frame, which was heavily gusseted in the steering head area but not so rigid around the swinging arm pivot. Although the seat was fixed in place, there was easy access to battery, tool kit and air cleaner via the easily-removed side cover. Gearing was extra high, giving a theoretical top speed of 115 mph (185 km/h).

Re-named as the T500 II Titan for 1969, changes were many, including the addition of a few kilos. Engine power was up marginally to 47hp with a marked increase in mid-range torque (thanks to revised porting and 32mm Mikunis replacing the 34mm jobs, which also significantly enhanced fuel consumption), the tank and side covers restyled into a more appealing shape and décor, and the overall appearance much less dumpy thanks to lighter mudguards and the increased overall length. There was now a grab-rail for the pillion passenger, better instrumentation, a friction steering damper, and as a concession to US tastes, high-rise handlebars. Interestingly, the Titan was still sold in UK as the Cobra, because well-known dealers Read Titan had the name registered for motorcycle use.

In this basic form, the Titan continued with just colour changes, plus a short-lived Triumph-style tank-top rack on the T500 III of 1970. One problem that had been highlighted was the tendency of 3rd, 4th and 5th gears to chop out if the motorcycle was subjected to prolonged periods of high speed. This was put down to oil starvation, so for the 1973 T 500 K, gearbox oil capacity rose from 1200cc to 1400cc. For some reason known only to the Suzuki marketing department, the T 500 gradually shed horsepower, dropping to 44 hp, with peak power developed at 6,000 rpm instead of 7,000. Cynics suggested that this was a ploy to make the slow selling GT380 and GT 550 triples more attractive to the buying public, but if so, it backfired.

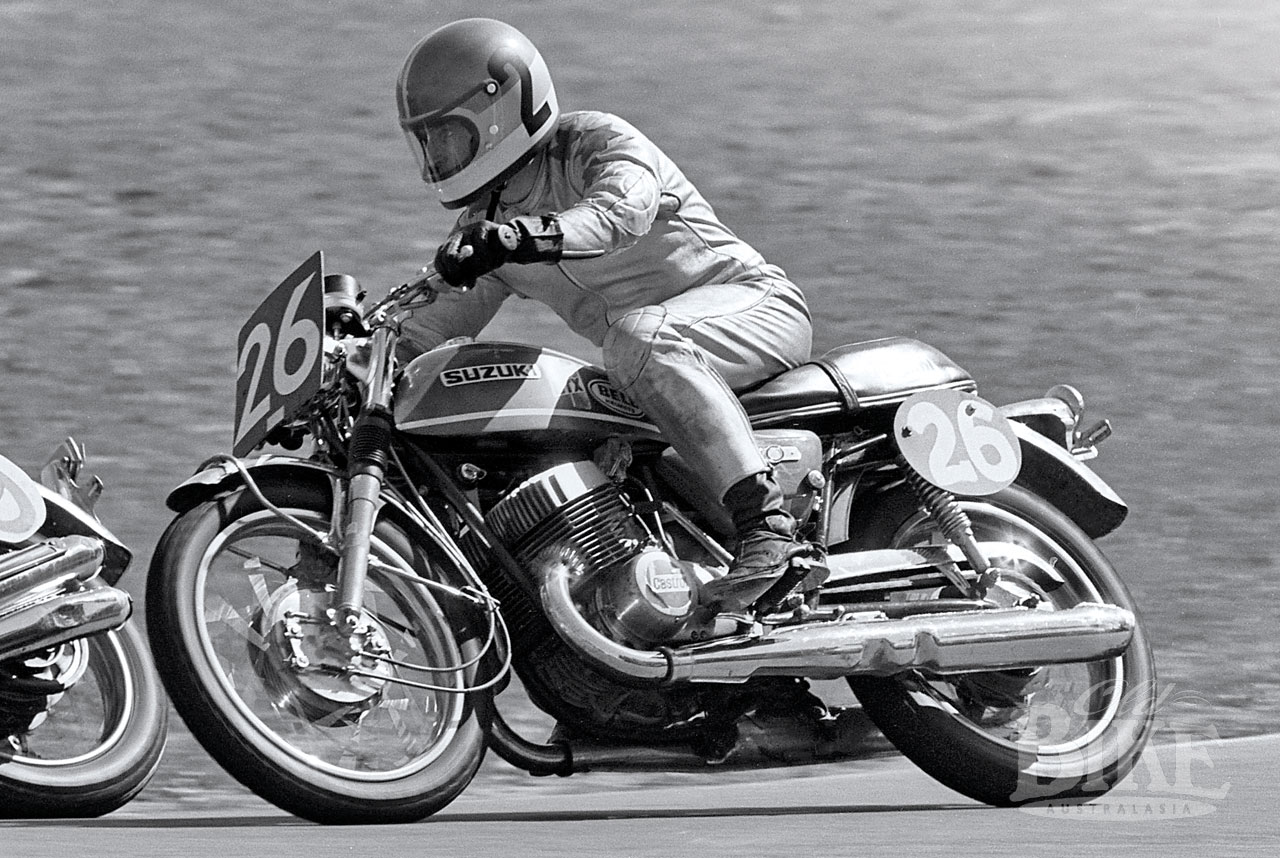

British T500 sales receive a considerable boost when Frank Whiteway won the 500cc Production TT at the Isle of Man on a T500 entered by dealers Crooks Suzuki. The term ‘production’ was only loosely applied, with porting mods, carburation changes, and modified internals for the silencers, resulting in a power output exceeding 60hp and a top speed of 130 mph. The winning T500 also featured a racing style tank, half fairing, and rear-set footrests, rear brake lever and gear lever. Production? Hardly, but the sales boost was gratefully accepted by dealers and Suzuki alike. And with a price tag in UK of #425 (£70 more than a Triumph Bonneville, the T500 needed all the help it could get). In Australia and New Zealand, the T500 turned in some admirable track performances, including a surprise win for dirt track star Bill McDonald in winning the 1969 Unlimited Production Race at Bathurst. The model also served as the basis for numerous race bikes, especially in New Zealand where the combination of highly tuned T500 engines and Roberts frames proved a very successful combination. Joe Eastmure turned in some giant killing performances on his T500 special which was tuned by Bob Burgess.

Probably the most successful example of the conversion of the T500 engine to a race tool was the motorcycle built by Aussie GP legend Jack Findlay and Danielle Fontana in Milan in 1970. Using a modified T500 engine from a much-travelled road bike, the pair installed it in a Seeley frame and Jack won the Ulster 500cc Grand prix in 1971 – his first World Championship win and Suzuki’s first win in the 500 class. It was entirely a private effort – the only support came from Suzuki GB who loaned Jack two pistons to use at Ulster – and which he had to return after winning the race! That machine was further developed by Fontana with a new light-gauge frame, and was known as the Jada, from the first two letters of their Christian names. On the Jada, Jack scored two rostrum positions in the 1972 GP season and was holding third in the Isle of Man Senior TT when the front frame tubes broke. His overall eighth position in the championship standings earned him a place in the Suzuki Italia squad for 1973 on works-supplied machines.

The 1975 T 500 M was the final incarnation for the model with its drum front brake. Featuring styling cues from the GT750 triple, the GT500, introduced in 1976, was an attempt to squeeze a few more years from the design which was facing extinction from increasingly savage anti-pollution laws, particularly in the United States. On the GT 500 A, which gained CDI ignition, the engine was in the same soft specification of 44 hp, now at 6,000 rpm, while weight had again risen sharply to 187 kg. A single disc front brake, sourced from the GT 380/550 added a touch of modernity, with larger (35mm) diameter front forks and instruments from the same models. Even the fuel tank on the GT 500 A came from another model; the GT750, with the flap for the radiator cap blanked off with a plastic cover. In keeping with the range styling, the headlight shell, side covers and oil tank were painted matt black. The end finally came in the form of the GT500 B of 1976, which shared the showroom floor with Suzuki’s all-new GS750 four-cylinder four stroke and not surprisingly sold like kittens. The popularity of the new ‘four’ also killed off the three-strong range of two stroke triples.

If there was one common criticism of the big twin, it is vibration. According to one report of the second model, “The carburetion and porting alteration introduced as an almost immediate reaction to the reception of the Cobra have given the Suzuki a delightful spread of torque; 2,000 rpm in top gear is quite acceptable to the motor, and the engine pulls sweetly up to about 3,500 or 4,000 before vibration sets in. When the vibration does start it is severe and becomes quite remarkably uncomfortable above 5,000. To use the 500 to full r.p.m. limits is an unrewarding experience as one’s foot can be firmly but steadily shaken off the footrest, as one’s hands go to sleep under the shaking.” The handlebars were rubber-mounted to combat the vibration, and even the mirrors had rubber dampers in the stems in a mainly futile attempt to produce a clear image.

The front drum brake was another oft-criticised area, despite its rather good looks. The brake generally fades quickly and this has been ascribed to the hub distorting as heat builds, leaving the shoes with reduced contact with the brake drum.

Speaking of heat, Suzuki was quick to address the notion that a whopping great twin cylinder air-cooled two stroke would have trouble staying cool enough. Suzuki sent a bunch of US journalists on a test ride through Death Valley in the middle of summer, and to everyone’s amazement, the bikes all emerged happily out the other side.

In terms of restorability, the T500/GT500 shares many parts with other models, including pistons from the GT750 which are heavier and less prone to seizing than the earlier types.

When the 500 twin was finally phased out, it was a sad day for many dealers and customers, as the model had attracted somewhat of a cult following in its life. It responded exceptionally well to tuning and formed the basis for a great number of successful club level racers, as well as more than a few machines that achieved notable results even at Grand Prix level, plus, of course, that famous TT win. In New Zealand, the genius of Steve Roberts’ chassis and numerous engine fettlers produced machines that could, and did, see off opposition in the hands of some of the world’s top riders.

But by 1977, the big two strokes were an endangered species, legislated out of existence, especially in USA. We can only surmise just what could have happened had the GT500 been allowed a few more years of development – electric starter, reed valve induction, more sophisticated exhaust system? It was already a damn fine motorcycle.

Last of the line

The featured motorcycle here represents the end of the line for the Suzuki twin. It is a 1976 GT500A, and as such, one of the rarest in the lineage that remained in production for ten years. The model shares styling cues from the GT750A and the all-new four-stroke four cylinder GS750, such as the décor and tank striping. Three colours were listed; black, blue or red. The 500 also shared the single disc front brake found on the new GS750 and the seat was completely redesigned along similar lines. Essentially, of course, the GT500 differed little from the earlier models, apart from the disc brake that appeared first on the GT500A. The subsequent B model also had the black-painted side covers used on both the GT750 and GS750.

Owner Michael Goodwin has collected numerous awards for the superbly presented Suzuki, which he purchased from fellow Macquarie Towns (NSW) club member Dick Arter. “Speaking to Dick at Bathurst one year I found out he had 2 GT500s but really only wanted to restore one of them,” says Michael. He agreed to part with one and settled on a price so I bought it. He had made a start on both bikes but really only wanted to complete one. Dick had powered coated the frame and re-spoked the wheels and started work on some other bits and pieces. It was at this stage he decided to focus on one bike, so he fitted the better parts to the one bike which make sense. The GT500 I bought required an extensive amount of work and many parts sourced as I wanted to keep it as original as possible. The tank was extremely rusted but mainly on the inside with only one spot penetrating to the outside. The bike had the seat attached but the base, foam and cover were well beyond help and needed replacing. The same applied to the mufflers which were rusted beyond repair the entire length on the underside. The bike has an extensive amount of chrome all of which was pitted and rusted including the fork tubes. Basically it was a sound motorcycle which I wanted to get back to its original glory. The engine wasn’t bad, in fact I haven’t even restored this, just carefully cleaned the metal which came up very well.”

It certainly did, and the rest of the bike is just as impressive. Even hard to get items such as the indicators, rear shocks and tail light are correct, as are the unusual brown-faced instruments (shared with the GS750). “The paintwork was done by Mototech at Smithfield, and Pioneer Plating at Moorebank did the chrome,” adds Michael. “Fifth gear is a bit dodgy so that will need to be addressed at some stage.”

“My history with the model goes back to the 1970 Castrol Six Hour where I rode a T500 in partnership with Allan Dale. Unfortunately as a result of my crash round the back of the circuit the bike was badly damaged and we did not finish. All these years later I was looking for a project and a bike to restore not just any bike but one that meant something to me.”

Specifications: Suzuki GT500B

Engine: twin cylinder air cooled piston-port two stroke

Bore x stroke: 70mm x 64mm

Capacity: 492cc

Compression ratio: 6.6:1

Carburetion: 2 x VM32SS Mikuni.

Lubrication: Suzuki CCI injection

Gearbox: 5 speed with helical-cut gear primary drive.

Starting: Kick only

Electrics: Denso 12-volt crankshaft mounted alternator with Electronic Ignition.

Frame: Welded steel tubular, full double cradle.

Brakes: Front: Hydraulic single-caliper disc

Rear: 200mm single leading shoe.

Suspension: Front: Oil damped telescopic forks.

Rear: Five-way adjustable spring/damper units.

Wheels/tyres: Front: 3.25 x 19 • Rear: 4.00 x 18

Wheelbase: 1460mm

Ground clearance: 160mm

Seat height: 81cm

Dry weight: 187kg

Fuel capacity: 14 litres.