Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

The basic design spanned nearly 30 years of production, and the Ariel Square Four has legions of fans more than half a century after the last one was made.

The story of the Ariel Square Four must start with the young Edward Turner, who in time, would rise to become the most powerful figure in the British motorcycle industry. But it was a different situation in the mid 1920s, when young Turner was a struggling engineer in London, who was cobbling together a 350 cc overhead camshaft-engined motorcycle of his own design in a tiny workshop. He had dreams (and designs) of producing a four-cylinder machine, but this was way beyond his modest means, and although he had hawked the concept around the trade, there were no takers. Then, during a visit to Birmingham with his blueprints under his arm, Turner met Jack Sangster, the owner of the Ariel company at Selly Oak, and Sangster agreed to give the youngster a drawing office, as well as an assistant – Bert Hopwood. Turner reasoned that his square-four design overcame the bugbears of the normal in-line four which, when mounted transversely in the frame was too wide, and when mounted fore-and-aft, resulted in an overly long wheelbase.

What emerged was a 500 cc design with a chain-driven overhead camshaft, with the drive to the gearbox taken from the left-hand end of the rear crankshaft. It was in effect a doubled-up vertical twin, with the two cranks coupled by gears. The prototype engine was mounted in the lightweight frame used for the company’s 250 cc single, but by the time the new model was ready to be displayed at the 1930 Earls Court Show, the engine had been transferred to the more robust chassis used for the 500 cc Ariel single. A hand-change four-speed Burman gearbox was used initially. The Square Four (catalogued as the model 4F) caused a sensation at the show, sharing the limelight with another new ‘four’, the V4 Matchless Silver Hawk.

The economy, on the other hand, was on rapid downward spiral following the Wall Street crash, and even though Ariel was gearing up to produce the new model for 1931, the company was already in serious strife. So serious in fact, that by 1932 Ariel was bankrupt, and was only saved by the injection of private capital from Jack Sangster, who reformed the company into Ariel Motors (JS) Ltd. Staff numbers were slashed and the majority of the factory leased out. Motorcycle production shrank into one small section of the premises, and the ranged of models trimmed.

Surprisingly, given the austerity of the times, the big-ticket Square Four remained in production, but the engine was scheduled for a major redesign in the coming years. Early examples suffered from insufficient cooling off the cylinder head and rocker box, resulting in frequent blown head gaskets. To encourage sidecar use, the capacity was quickly upped for the second year of production to 587 cc, by the simple expedient of over-boring each cylinder by 5 mm. For 1933, a four-speed, positive stop foot change gearbox was added.

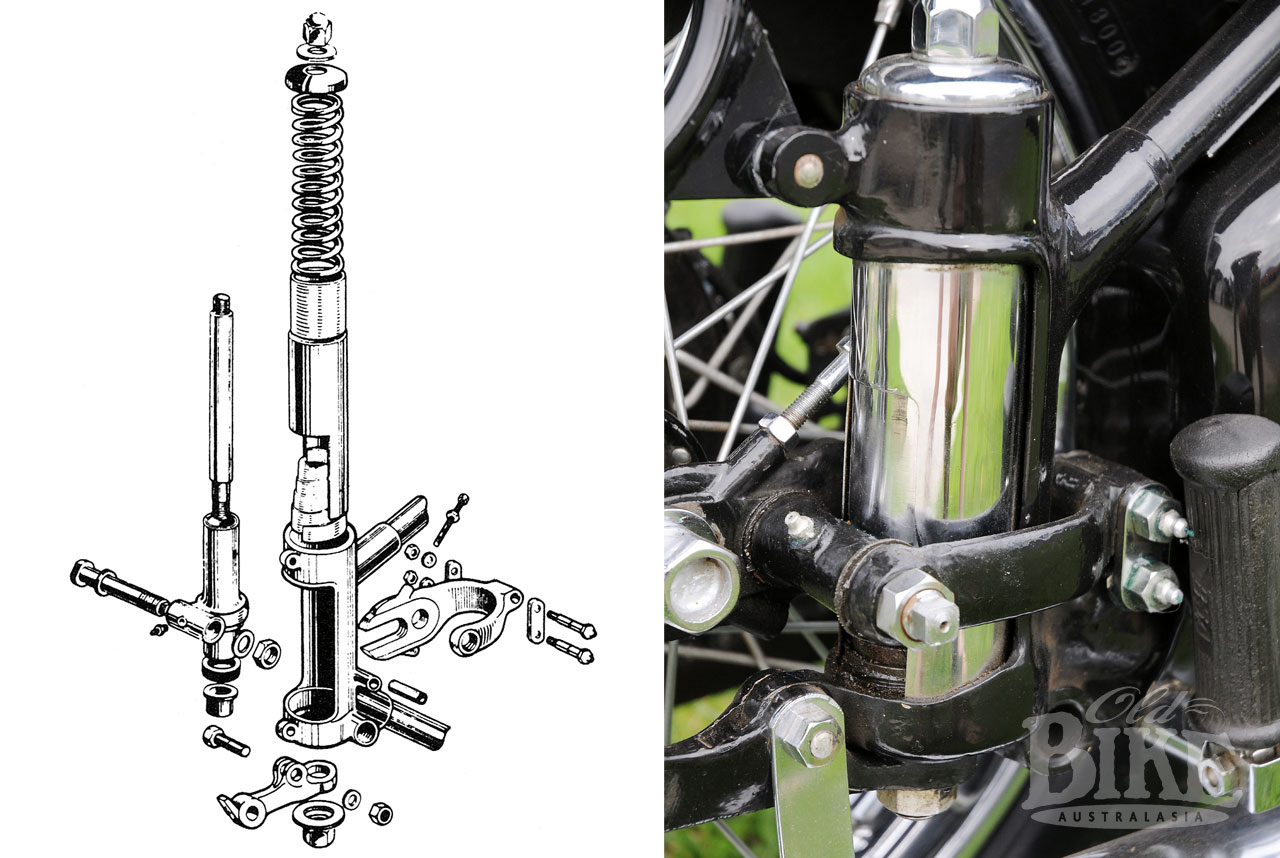

In the next major redesign, towards the end of 1935, the costly overhead camshaft operation gave way to pushrod overhead valves. Down below, the original design which had overhung cranks (with the exception of the driving crankshaft on the left rear) was completely redesigned to feature full crankshafts, coupled by gears on the left hand side, rather than in the centre. As well as the 600 cc version, a full 1000 cc job was also on offer when the new model (known as the 4G) went on sale in 1937. The larger model put out 38 bhp at 5,500 rpm and Ariel claimed it would pull from ten to one hundred miles per hour in top gear. In 1939, a unique form of rear suspension was added (as an option) to the Square Four, and also to the single cylinder red Hunters. This was a form of plunger suspension, but with pivoted links that allowed the rear wheel to travel through an arc, giving constant chain tension. Both the 600 and 1000 versions dispensed with Amal carburettors in favour of the Solex 26FH carburettor and from 1938, the Solex 26AH.

Just when things were looking rosy, along came the war, and much Ariel’s production was switched to armaments and other engineering, although a 350 cc military model based on the 1939 Red Hunter was produced. When peace returned, motorcycle production at Selly Oak at first concentrated on the 350 single, but eventually the Square Four went back into production, but in 1000 cc form only. By this stage, Ariel had new owners – the BSA Group – but the company, at least publicly, remained in charge of its own destiny, with former racer Ken Whistance at the helm. The Square Four again was the subject of a major redesign (the Mark I), with telescopic front forks and the substitution of aluminium alloy for major engine components, including the cylinder block and the head. This chopped a whopping 33 pounds (15 kg) from the considerable all-up weight. The engine was still in its pre-war ‘two pipe’ form, with the exhaust ports exiting front manifolds attached to the cylinder head, but it 1954 another major redesign took place to produce the Mark II version – the ultimate incarnation of the design.

When the British magazine Motor Cycle tested a Mark II in 1956, the report said “few, if any, other types of machine provide the same feeling of exhilaration. The driver of a “Squariel” has four cylinders and 1,000 cc at his fingertips, waiting to respond to his every whim.” The tester confirmed the amazing flexibility of the engine, which pulled ‘snatch-free’ from 10 mph to the top speed of 102 mph. It also praised the braking capabilities, saying “ with such an abundance of power and speed at one’s disposal, the subject of stopping quickly and safely becomes one of prime importance. The magnificence of both the Ariel’s brakes cannot be exaggerated. The functional-looking full-width alloy front brake was fade-free, delicate in operation and completely trustworthy under hard application and in all circumstances.” The five-gallon fuel tank allowed almost 300 miles (480 km) to be covered between fuel stops.

The Mark II featured four separate exhaust pipes, two on each side, which emerged from handsome polished alloy manifolds and curved downwards to join a single muffler on each side. With high quality fuel becoming available, compression ratio was raised to 7.2:1, with power subsequently up to 42 bhp at 5,800 rpm. Carburation was now by a variable choke MC2 SU carburettor, fitted with an air cleaner. However while the sporting Ariel singles gained a very effective new frame with swinging arm rear suspension, the Square Four soldiered on with the plunger/link design, and would do so until it reached the end of its production in 1958, by which time the UK price was £336/16/6 included the dreaded UP Purchase Tax. Indeed, this was the end of the line for all four-stroke Ariels, replaced by a new wave of two strokes headed by the Val Page-designed twin cylinder Leader.

The Square Four had a rebirth of sorts in the late 1960s, when the Healey brothers, George and Tim, produced the Healy 1000/4. Tim had been drag racing a machine with a highly modified Square Four engine, and with what he and George had learned about making the engine work more efficiently (and stay together longer), they came up with the idea of their own complete machine. This used the MkII engine which had carefully thought out modifications to the lubrication system, including a separate oil filter in an Egli-type spine frame (made by Slater Bros in England) with the motor hung underneath. Metal Profiles front forks and Girling rear units were used, with a huge Grimeca double sided front brake. The massive top tube of the frame carried the oil, and the improved lubrication and subsequent cooling allowed the compression ratio to be raised from 6.7:1 to 7.5:1, giving a 10% increase in power. The Healey brothers managed to carve around 60 pounds in weight from the original model, which further enhanced performance. Inspired by their creation and buoyed by the interest it created from prospective buyers after its release at the 1971 Earls Court Show, the brothers abandoned their trucking business in the Midlands and moved to Reddich, near the old Royal Enfield factory, to concentrate on producing the 1000/4 as well as spares for other Squariels, but from 1971 to the end of the show in 1977, only 28 complete machines were built. Today, Healey 1000/4s bring big prices on the rare occasion one comes up for sale.

Wollongong Squariels

Former sidecar racer Neville Stumbles recalls there were several Square Fours around his stamping ground of Wollongong, including his own – a 1953 Mark II in the optional blue colour scheme.

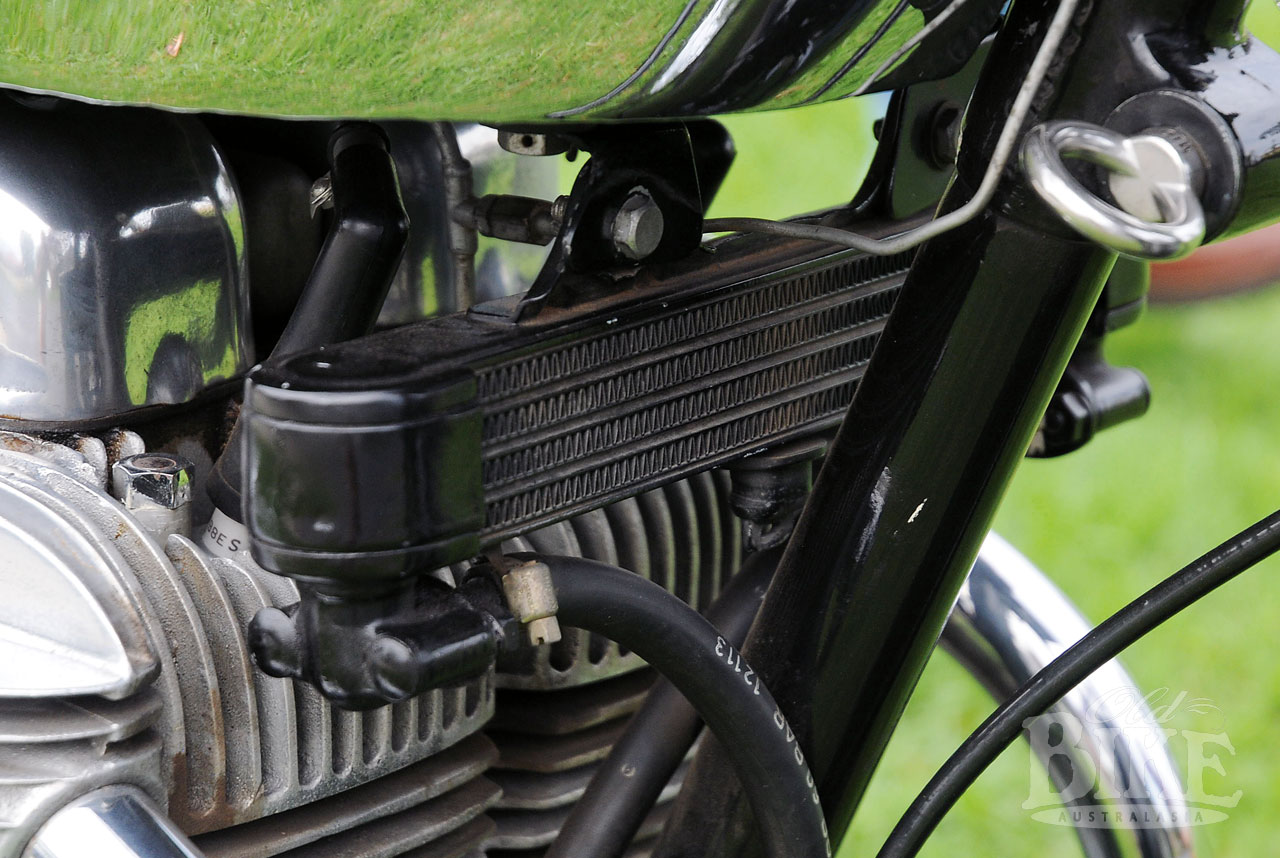

“My S4 was a four pipe model, but with the 6 pint oil tank. Kevin Cass had a similar model, but with the 1 gallon oil tank. Both of us had Tilbrook sidecars attached, and I recall that the Square Four was the only motorcycle I owned that could haul a sidecar easily on solo gearing because of its torque. One advanced feature was the ability to remove the rear wheel without dislodging the chain or rear brake. However, on one occasion while ascending Bulli Pass, a rear piston seized in its sleeve and punched a hole in the crankcase. Gordon Spence (who employed Doug James in his Wollongong dealership) repaired the hole in the crankcase by welding it up, no small feat in the mid 1950s. Gordon was rather sceptical about the car type Solex carburettor fitted as standard equipment, so he modified one of the rear frame petrol tank supports and fitted an Amal carburettor. This was easier to tune than the Solex and I had no further trouble with the bike. I think the overheating problem, for which the Square Four was known, was caused by a gradual blockage of mud from the front wheel becoming lodged in the rather small air passage between the front two cylinders. In retrospect, I believe that all Square Fours should have been fitted with the 1 gallon oil tank, plus an oil cooling radiator.“

A Squariel for Steve

In previous issues, we have featured several of the motorcycles in Steve Thompson’s extensive collection, among them his fleet of Suzuki GT750s and BMW R75/5. But his latest acquisition is from another era altogether – from 1956 to be precise. This 1956 MkII Square Four was recently purchased from Arthur Charlton from the NSW Central Coast, who owned the bike for a number of years and undertook a cosmetic restoration during this time. The engine was rebuilt by a man who knows his way around Ariels, Bathurst resident John Shanks. John raced Ariel singles very successfully in the 1950s, and these days is a regular at rallies in the NSW Central West on his immaculate MkII Square Four, which is finished in the very fetching blue décor rather than the black of Steve’s example. There was also a colour which Ariel called Deep Claret available in the MkII. Arthur was conscious of the fact that lubricant quality is the most vital factor in maintaining a happy powerplant, and sensibly fitted an oil pressure gauge, which hides almost invisibly on the right side of the steering head where it is clearly visible by the rider. There is also a massive oil tank, holding a full gallon of oil, and Arthur also fitted an after-market oil cooler, just to be on the safe side.

On the day I arrived for the photo shoot, Steve was still screwing the number plate to his latest purchase, and had only ridden it a few metres up his driveway at that stage. Starting is a simple process – raise the choke lever under the Solex carburetor and kick away. Just two kicks were necessary to bring the engine to life, whereupon it settled into a gentle idle with appropriate light whirring noises coming from inside the formidable power unit. I suspect that some of this music comes from the straight-cut gears that link the two cranks. He suggested I ride the Ariel the few kilometers up the road to where we had selected a location for the photos, so here was my first taste of piloting a Square Four. Straddling the bike, it is nowhere near as wide as you might expect, after all it really is a doubled up twin, and the weight distribution gives a low centre of gravity. I imagine the centre stand gets little use, due to the muscle involved in heaving the machine onto it, so it was just a case of flicking the quite adequate side stand back and we were ready to roll.

The clutch is feather-light and completely vice-free in operation. As you would expect, the engine simply oozes torque, and is extremely smooth and vibration-free. There is no need for revs, you just keep changing up. In fact, after one stop I mistakenly took off in third, but there was hardly a whimper of protest from this willing engine. In operation, the engine exudes a throaty drone, very car-like. I must say that it did feel a bit inclined to wallow over bumps, but most plunger-frame bikes do, and considering the mass of the square Four, it was quite acceptable, and the suspension itself actually worked reasonably well. Many Square Four owners however say the Frank Anstey-designed link-and-plunger rear suspension is the weakest point in the chassis design. It was meant to keep the rear chain tension constant, but in reality it creates more problems than it solves, and is prone to wearing the many small plain bushes in the linkage, which exacerbates the handling problems. The only flaw was the rather ineffective front brake, which I suspect simply needs refurbishing, as Ariels generally are good stoppers.

It was a sad day for motorcycling when the Square Four was axed from the Ariel range, because it represented a machine with genuine character in a sea of me-too models. But it fell under the slash of the accountants’ razor at the soon-to-be-struggling BSA concern, deemed too expensive to produce. A real pity because with a more modern chassis (which could easily have been sourced from the BSA range) and the long-overdue attention to the inherent lubrication problems, the Square Four could have gone on for many more years.

Thanks once again to Steve Thompson for making one of machines available to us; a bike that we will be seeing regularly in future as Steve is a very keen rally-goer, although he has the enviable problem of a vast array of fine motorcycles from which to choose for the occasion.

Model Years Produced Production

4F-500 1931–1932 = 927

4F-600 1932–1940 = 2,674

4G-1000 1936–1948 = 4,288

Mk I 1949–1953 = 3,922

Mk II 1953–1958 = 3,828

All Models 1931–1958 = 15,639

1958 Ariel Square Four Specifications

Engine: Air cooled 4-stroke ohv square four

Displacement: 997cc

Bore x stroke: 65 x 75mm

Compression ratio: 7.2:1

Carburation: single SU carburettor

Claimed power: 42hp @ 5800rpm

Transmission: 4-speed

Electrics: 6V 20A/h battery, coil ignition

Frame: Steel diamond

Front suspension: Telescopic forks

Rear suspension: Twin link-and-plunger units

Front brake: 8-in (203mm) sls drum

Rear brake: 8-in (203mm) sls drum

Front tyre: 3.25 x 19in

Rear tyre: 4.00 x 18in

Wheelbase: 56 inches / 1422mm

Seat height: 30 inches / 787mm

Fuel capacity: 5 gallons / 23 litres

Weight: 425lb / 197kg dry

General equipment: Full tool kit, tyre pump, 120 mph Smith’s speedometer, pillion footrests.