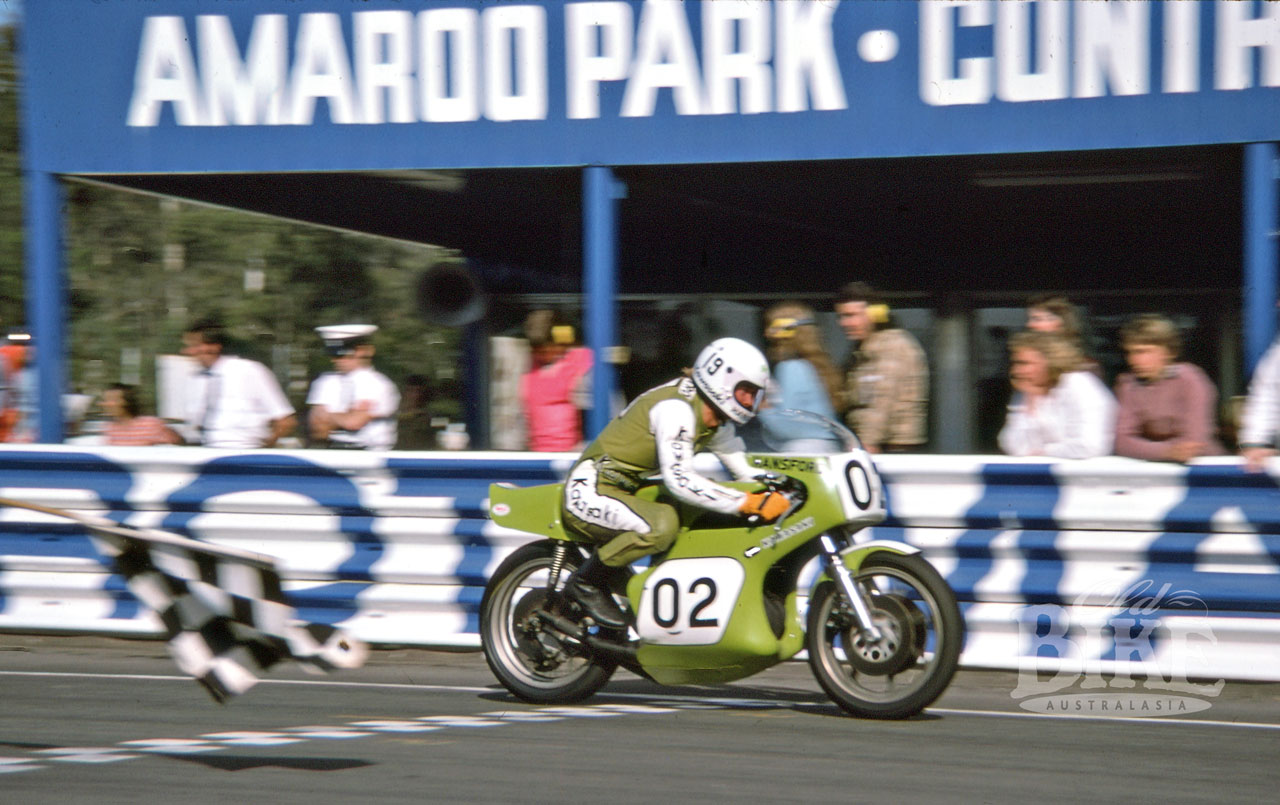

A road racing circuit, motocross track, tar hill climb, oiled-dirt short circuit (and briefly, a speedway). And less than an hour from Sydney CBD. A dream? No, for 35 years, this was Amaroo Park; the brainchild of developer Oscar Glaser, and in its original conception, was to be a facility perhaps unique in the world, not just Australia.

Glaser ran North Sydney Traders which did all kinds of commercial and retail business including earth moving and plant equipment hire and sale. NST was one of the first to offer an equipment and specialised tool hire service for tradesmen, now a common practice but rare in the late 1950s. Glaser owned a large tract of land, approximately 250 acres, in Annangrove, near Dural in the north west of Sydney. It was pretty rugged country, with Cattai Creek winding its way through it, craggy rock outcrops, mobs of kangaroos, swamps and very little flat land. The valley was officially called “Black Captain’s Gully” after the last of the aboriginal tribal chiefs in the area, who was known as Black Captain. “Amaroo” is an aboriginal word meaning “peaceful”.

Glaser formed Amaroo Park Pty Ltd which later leased the entire operation to Amaroo Country Sporting Club Limited, and besides the various forms of motor sport, the venue was to include several swimming pools including an Olympic quality pool and diving tower, tennis courts, bowling greens, extensive picnic and barbeque areas, a restaurant, a motel and caravan park, function rooms that could be hired by clubs, and even a ballroom and dance centre. Membership to the Country Club was opened to the public in 1963, and stage one of the development was scheduled for completion in March the following year. The opening offer of debentures called for 250 foundation members at £25 per debenture unit, producing £6,000, or one-third of the estimated cost of construction the clubrooms .

It was a time of unprecedented interest in motor sport. As well as the under-construction Oran Park at Narellan, another track at nearby Hoxton Park reached the stage of submitting a development application, and some preliminary work was done before the project was abandoned.

At Amaroo Park, no fewer than five circuits were to be included in the initial construction, the highlight being a 2.5 mile Grand Prix circuit on the eastern side of the property. Initially, an extremely rugged scrambles track was hacked out, running along the valley floor and up and down the rocky escarpment. This was inspected by the Police Department in February 1962 with a recommendation to the Chief Secretary’s Department that a licence under the NSW Speedways Act be granted. This predictably took longer than anticipated, and the first open meeting was set down for August 26th, 1962, with an official opening ceremony for the Amaroo Park complex held during the meeting. Stars of the day were two riders destined to go on to great things in other branches of the sport: future speedway legend Jim Airey, who won both the Senior and Aces Invitation, and future World 250cc road race champion Kel Carruthers. There were many complaints about the rocks that littered the track, causing numerous punctures and falls. A second open scramble meeting was held in late October, and two more in 1963, but the circuit’s reputation as a machine wrecker was intensifying, and the circuit was abandoned following the open meeting in February 1964 which drew only 27 entries.

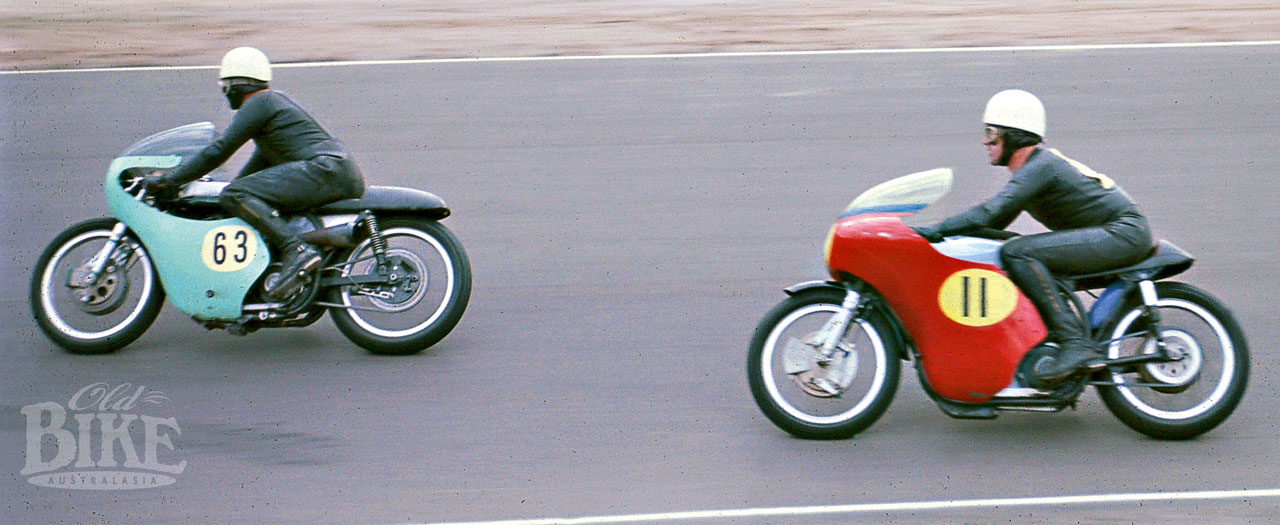

On December 1st, 1963, the second Amaroo track – the oiled-dirt Short Circuit – opened. This proved to be an immensely popular circuit amongst car clubs as well as for bikes, with a high sandstone natural grandstand providing excellent viewing for spectators. The dominant Northern Centre riders soon discovered the new Amaroo Short Circuit, with Herb Jefferson, Dave O’Brien, Keith Davies and Kevin Fraser regularly scooping the pool at the frequent open meetings.

Meanwhile, the tar hill climb, primarily a car venue, opened in the far northern corner of the site, as did a Go Kart track, but nothing further was heard of the proposed Grand Prix circuit, and the owners began to eye an area at the western side with a view to building a smaller tarred circuit of just under 2 kilometres in length. As the old scrambles track gradually returned to nature, the Short Circuit up the hill boomed, hosting a meeting a month throughout 1965. Indeed, Short Circuit racing in Sydney was going through a major revival, with the new Nepean circuit hosting its first open meeting in October 1965, as well as regular racing at the Vineyards track near Windsor, at Eastern Suburbs MCC’s Arcadia track, and at nearby Glenorie which was owned by Western Suburbs MCC.

While the dirt track was raging away, there was much activity at the opposite end of the property, where the new 1.93 km road racing circuit had been hacked out of the side of a small gully. Space was tight, just like the track itself, as Cattai Creek ran through the valley and virtually dictated the shape of the circuit. Amaroo CSC itself however was in financial straits, cost overruns on the track’s construction and shortfalls in revenue leading to the sacking of its full-time promotion secretary and the out-sourcing of such duties to individual committees. The proposed debenture issue had failed to tempt subscribers, meaning that virtually none of the infrastructure or non-motorsport amenities had come to fruition. Eventually an administration building (which could be hired as clubrooms) was constructed, and a café/shop adjacent to the main road added.

The road racing circuit had no real straight as such, with a right hand bend halfway up the hill after the starting area, bordered by a fairly savage looking wall constructed from boulders on the outside of the track. This un-named bend was the scene of numerous disasters for both cars and motorcycles, and following a major pile up in the Castrol 1000 (Six Hour) Race in 1970, was eased by tarring the verge of the corner right up to the Armco fencing on the inside of the track. As well as making the corner wider and slightly safer, it made the run up the hill quicker and had the effect of lowing lap times.

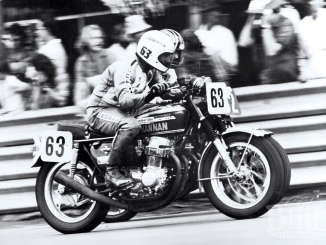

The opening motorcycle meeting (which preceded the first car meeting – a club day – by six weeks) on February 26th, 1967 was organised by Parramatta dealer Barry Ryan on behalf of the Amaroo Motor Cycle Committee, and featured a 40-lap race for Production bikes as the first race. Production racing was to become synonymous with the circuit throughout its entire existence. After a colossal amount of work by the committee which included stalwarts like Paul Giles, Dave Elliot, Norm Askew and George Slatyer, the first motorcycle meeting was almost washed out. Saturday’s practice was conducted in glorious sunshine, but the weather did a back-flip overnight and the races were all run on a very wet track. Top man of the meeting was Len Atlee, who rode three different machines and won both the Junior (on Barry Ryan’s Cotton) and the Unlimited Feature (on his own Manx Norton). The Production Race was cut from 40 laps to 30, and won by Larry Simons on his BSA Lightning, ahead of the Bultaco Metrallas of Kevin Fraser and Alan Arnold.

With lap times meaningless from the wet opening meeting, the first ‘dry’ records were established at the second meeting on 21st May, which attracted top names Jack Ahearn, Ron Toombs, Len Atlee and Bill Horsman, plus sidecar stars Dennis Skinner, Noel Manning, Orrie Salter and Bob Levy. In winning the Unlimited Feature, Ahearn left the outright lap record at 63.9 seconds. At the third meeting on September 17, Ahearn, now mounted on a Dunstall Norton Atlas, slashed 2.4 seconds from his previous best. A further meeting took place on December 27th with another Atlee benefit, but by now Amaroo Park was in serious financial trouble. The car meetings had all been thinly supported, with much grumbling about the facilities for spectators and competitors alike, and with good reason. There was no seating for spectators other than the abundant rocks, few toilets, and no power or shelter in the pits. Little thought had been applied to drainage, with the result that the lower reaches of the circuit were frequently under water. With no money to build the necessary improvements and rectify the faults, the Road Racing track effectively shut down in early 1968, although the Short Circuit continued on a reduced basis.

For more than two years the majority of the complex lay silent, until Glaser did a ‘handshake’ deal with the Australian Racing Drivers Club to take over the operation. The ARDC in turn entered into co-op arrangements with Willoughby District MCC to run motorcycle events on the Road Racing track and on a new Motocross circuit, which was built in the same area as the original scrambles track but used much clean ground fill to obviate the problem with rocks. Ryde MCC took over the running of the Short Circuit and built that promotion into a very popular show, culminating in the track being awarded the Australian Short Circuit Championships for 1972.

After divesting themselves of the perennially fog-bound and loss-making Catalina Park circuit at Katoomba, ARDC swung its efforts behind Amaroo, instigating a continuous program of improvements to the Road Racing circuit that included much enhanced spectator facilities and a big makeover for the pit area. One of the first projects was the construction of a new race headquarters and commentary tower, which was completed in time for the re-opening meeting in May 1970. Victorian Peter Jones (TR500 Suzuki) won the main event, the 10-lap Jack Ahearn Motorcycles Feature from Kenny Blake’s H1R Kawasaki, but a new outright lap record went to Ron Toombs, mounted on another H1R, at 61.2 seconds. At the next meeting in August, Toombs (back on his 350 Yamaha) carved the record down to 60.4 seconds.

But the event everyone was talking about was the Castrol 1000 for Production motorcycles, set down for October. The race attracted not just massive interest but healthy sponsorship and prize money, with most of the country’s top riders jumping onto the previously unfancied roadsters. The race began in carnage however, with a big pile up as the field left the grid after the Le Mans start, then a major accident the following lap which saw the ambulance ushered onto the circuit, only to be struck by Garry Thomas’ Honda CB450, who was catapulted over the fence and into the scrub on the inside of the circuit. Eventually order was restored and the race settled down to a battle between the Triumph Bonneville of Len Atlee/Bryan Hindle, and the CB750 Honda ridden by Craig Brown/Roger Jackson. The issue was decided when the Honda spent precious minutes having its brake pads changed, eventually finishing second with another Bonneville ridden by Jack Ahearn/Graeme Besson third. Despite the accidents, the concept was decidedly a winner, and went on to become the signature meeting at the track for the next 13 years.

Willoughby club also pioneered the ground-breaking Chesterfield Superbike Series, coining the name many years before it was picked up overseas. The club and its energetic secretary Vincent Tesoriero were pivotal to having the Motocross track constructed, which opened in July 1971 and went from strength to strength thereafter. Tesoriero adapted the Chesterfield-style back-to-back short races to Motocross with the Mr. Motocross Series in 1974 – the title quickly becoming the biggest thing in off-road racing and continuing for more than ten years.

1984 was a watershed for motorcycle activity at Amaroo. Willoughby club had been at loggerheads with ARDC over circuit hire costs and had threatened to take the prestigious Castrol Six Hour to Oran Park unless an agreement could be reached. However at the opening meeting for the year, 27-year-old Jayne Litterick was killed in a crash on the infamous Wunderlich Corner onto the starting straight – a section of the circuit that had claimed two lives already. Covering Litterick’s races on the day was a television crew for the Mike Willesee Current Affairs program, and the fatality attracted unprecedented media coverage, leading to the ACU of NSW temporarily withdrawing the track’s licence. The ACU wanted the Armco fence shifted by at least ten metres to allow a run-off area, but this would have meant the loss of a section of the already minimal paddock area as well as the need to build a new pit entry road, and the ARDC would not hear of it. A knee-jerk reaction was to construct a dog-leg chicane inside the corner, which proved entirely unsatisfactory, especially for an event such as the Six Hour, which never returned to Amaroo. With its major promotion now based at Oran Park, Willoughby club gradually lost interest in Amaroo, and even the Mr Motocross Series abandoned the location for the 1983 series. The Short Circuit track was closed soon after.

Despite the loss of the high-profile motorcycle events, Amaroo Park continued as a popular facility for car racing, hosting rounds of the Australian Touring Car Championship as well as major races for sports cars and open-wheelers. As the race team transporters grew ever-more gigantic, Amaroo’s confines became even more cramped, but it was not the venue’s limitations, nor even the increasing complaints about noise and traffic congestion that led to its demise.

It is widely believed that the legislation that was bulldozed through NSW parliament in order to facilitate the construction of Eastern Creek Raceway (and to snaffle the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix from Phillip Island) contained a section that required one of the existing motor sport circuits in the state (Oran Park and Amaroo Park) to cease operations so as not to jeopardise the economic viability of the government-owned and taxpayer-funded Eastern Creek. The situation came to a head when the lease and management of Eastern Creek was offered to the ARDC, which packed its bags and departed Amaroo fairly quickly. The club had sustained heavy losses promoting the fledgling Two Litre Touring Car formula at Mount Panorama and needed the capital to stay afloat. A number of other suitors, amongst them the successful Stay Upright Motorcycle Training business, looked at purchasing the Amaroo site outright, but the gap in motor sport promotion, short as it had been, had effectively played into the hands of the residents and the local authorities, and any thought of continuing racing would have meant an expensive and lengthy legal challenge.

And so on August 23rd, 1998, with a club car meeting on the road circuit and a vintage motocross on the site of the former Mr Motocross venue, the gates closed for the last time. Despite concerns over the environmental sensitivity of the flora and fauna in the area, and the well known problem of the flooding of Cattai Creek, a bid of around $4 million saw the venue change hands, to be quickly earmarked for subdivision for more of the massive houses that now characterised the Annangrove suburb.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Jeff Nield, Michael Andrews, John Ford, ARDC archives.