- Longford, Tasmania

It’s been nearly 40 years since Longford, 30 minutes south of Launceston, hosted its last motor race. But until a few years ago, you could still drive around most of the public roads that made up this awesomely fast circuit. Then, in the name of progress, a new section of highway was laid, bisecting the circuit, which now lays in broken sections with nature rapidly reclaiming her territory. At 4.4 miles (7.1 km) to the lap, Longford’s roads formed roughly a triangle that twice crossed the South Esk River via wooden bridges. In the sixties, skin divers were stationed below both bridges to drag out anyone unfortunate enough to take the plunge!

The start and finish area used from 1959, adjacent to the famous old Water Tower that still survives as a relic in a paddock, launched the field for about one kilometre before plunging downhill and under the railway line through a magnificent brick Viaduct. The left/right flick led to a short, very narrow straight onto King’s Bridge across the river and into Longford township itself. The most famous landmark was, and still is, the Country Club Hotel which stands on the inside of the right hander leading onto Tannery Straight. There was a small matter of a railway line to be negotiated (jumped) before a very rapid section on the way to the right angle Tannery Corner. Downhill once again, the circuit swept across the picturesque Long Bridge and into the hairpin Newry Corner. Accelerating sharply uphill took you onto the awesome Flying Mile, which is more like a mile and a half if you include the flat out sweeping left that leads onto it. Then it was hard on the anchors for Mountford Corner, a 120-degree right leading back to the start/finish. Originally, the start/finish line was located at the end of the Flying Mile, but this was moved in 1959 around the other side of Mountford Corner, together with a new pit area and control tower.

Longford was reminiscent of the ultra-fast Continental circuits, with the long not-quite-straight stretches that demanded precision and commitment to put together the quick lap. It had every element required for a classic road circuit, including the blast through Longford village.

Our top title

Although it became more famous for car racing, notably the Tasman Cup, Longord came into being specifically to host the 1953 Australian TT for motorcycles. The TT had originally been offered to Tasmania for 1950, but no suitable circuit could be found. Late in 1952 a delegation from the Auto Cycle Council of Australia inspected the proposed layout and gave the thumbs up, subject to the section from the water tower to the viaduct (which was gravel) being tar-sealed.

Local identity Martin Coombe was determined that the opportunity should not be lost again, and, with Longford councillor Ray Hortle, formed the TT Racing Committee (TTRC), which in turn engaged the Tasmanian Road Racing Association (TRRA) to organise the event on February 27 and 28, 1953. It was Coombe who was the tireless worker for the cause, later upholding the interests of the bike fraternity as car-minded groups gradually took control of Longford. The State government gave permission for the roads to be closed for two days.

Ron Mackinnon, whose property ‘Mountford’ stretched from the South Esk river near the viaduct up to what became known as Mountford Corner (on both sides of the road) was a supporter, and used his wartime Army contacts to gain access to local Army Reserve groups, who provided logistical help in the form of radio communication around the circuit.

Public address was provided at all spectator areas, with commentary from a number of points around the circuit. This was a major undertaking for a local organisation which had no previous experience of such things, and a sporting association which had previously only organised racing on airfield circuits.

Considering the remoteness of the location, the TT drew a top entry, headed by the official state representatives Harry Hinton (NSW), Bill Anderson (Queensland), Maurie Quincey (Victoria), Alan Wallis (SA) and Peter Nicol (WA). On his home-made 250cc Manx Norton, Hinton ran away with the Lightweight TT, but in the 125 race, run concurrently, the favourite George Morrison was beaten by Victorian Keith Hambrook’s BSA Bantam. Quincey won the Junior 350cc TT after a fierce dice with Hinton, who broke a chain, while a similar fate befell runaway leader Anderson in the 500 race, giving Quincey another win. The final Unlimited TT was to be run over 12 laps, but the meeting was running late and the rail gates had to be opened to allow the evening train to pass through. The event was quickly cut to 4 laps, and once again Anderson’s rapid Manx made the running with Quincey doing his best to hang on. The Victorian timed his move perfectly, slipstreaming past on the final run down the Flying Mile and winning by a wheel. Both sidecar classes were run together with Bob Mitchell (Norton) winning the 500 and Frank Sinclair (Vincent) the Unlimited.

The 1953 TT was initially seen as a one-off event. It was extremely costly to organise and administrate, communications around the long lap were difficult, and the group that had run the meeting – the TT Racing Committee, specially formed for the occasion – ceased to exist after the event. However interest was rekindled, chiefly by Ron Mackinnon who wanted to see car racing on the track, and the Longford TT Racing Committee (LTTRC) reformed in 1954. After much hard work the show was on again for 1955. It was to be the final leg of reigning World Champion Geoff Duke’s Australian Tour, and the meeting attracted considerable attention, but few ‘mainland’ entries. On his works four-cylinder Gilera, Duke was timed at 144 mph on the ‘Flying Mile’, and despite some severe misgivings about certain aspects of the circuit he won both his races. Duke noted that the planks used to surface the bridges ran in the direction of travel and had sizeable gaps between them! In his first start, magneto trouble that knocked 1600 rpm off the Gilera’s maximum of 10,600 set in on lap 6 of the eight lap race, allowing local star Max Stevens on the ex-Quincey Norton to close within nine seconds when the chequered flag came out. A replacement magneto was flown across from Melbourne, and after a quick trip to Launceston to fit it, he returned to win again and he raise the lap record to a 92 mph average.

A lull in proceedings

Plans were laid for 1956 but, with the traditional March Labour Day long weekend fast approaching, the promotion was scuttled by a shipping strike which prevented cars and bikes, as well as vital communications equipment arriving from the mainland. One year later the racing returned, this time titled the Tasmanian TT. The expected dice in the Senior TT between Maurie Quincey and local Dave Powell failed to eventuate after Quincey’s Norton expired on the first lap. Earlier in Saturday’s program, Maurie had comfortably won the Junior TT. One Monday Powell and Quincey met again, and this time diced hard for the Unlimited title which went in Quincey’s favour. Local Peter Thurley won both 125 and 250 TTs, and Bernie Mack took a Sidecar double.

In 1958, Sydney printing magnate Len Deaton enjoyed the biggest day of his motorcycling career (he later took up car racing) when he rode his Norton to both 500 and Unlimited titles at the Tasmanian TT. Victorian George Huse was the 350 winner and Alan Lee the 250, with Peter Thurley on the Walsh Bantam BSA again winning the 125. Bernie Mack again rode his Norton to both scratch and handicap Sidecar TTs.

1959 was a pivotal point in the circuit’s history. Longford was awarded the Australian Grand Prix for cars, and the Australian TT for motorcycles for its March date. The cars drew a class entry headed by Stan Jones in his Maserati 250F, muffler king Len Lukey’s new Cooper Climax, and local star John Youl.

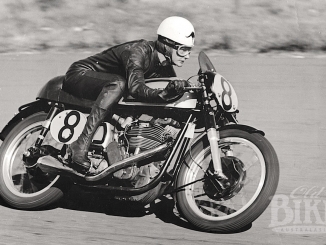

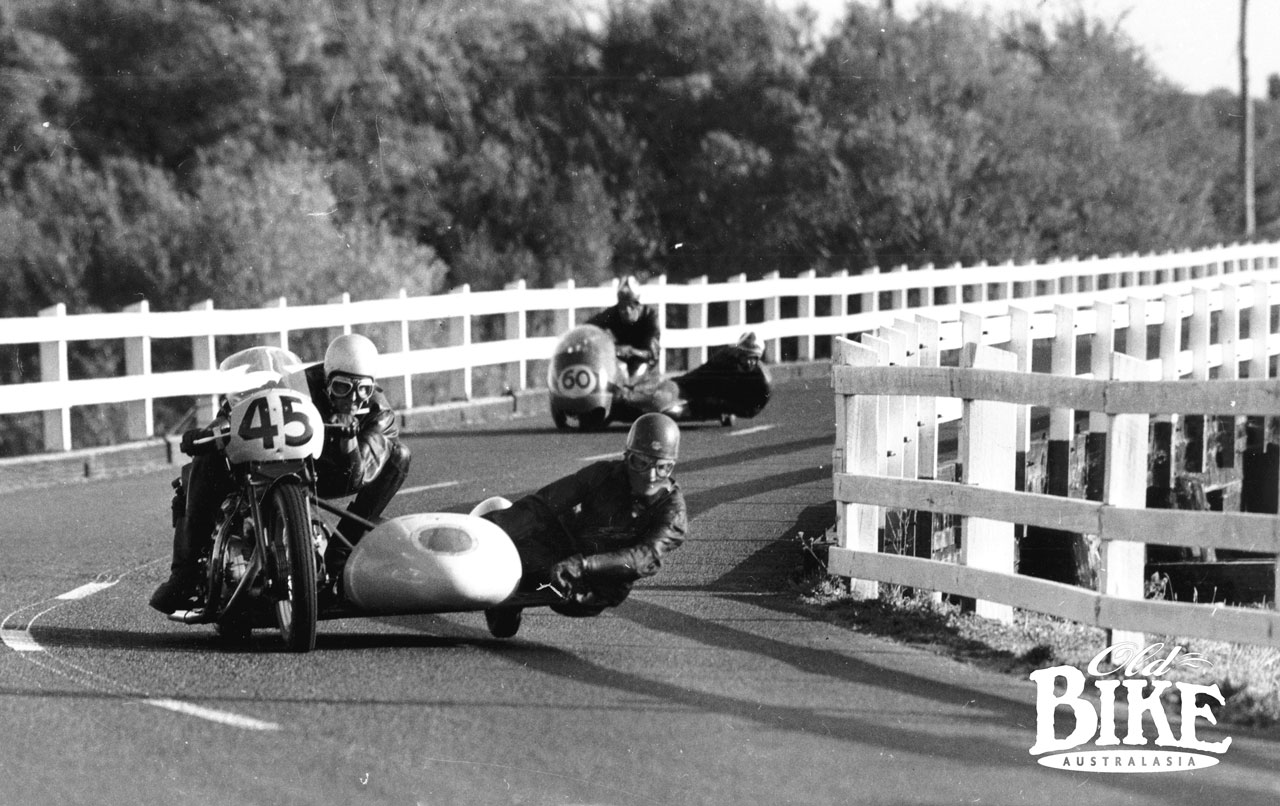

In the bike line up, rising star Tom Phillis secured the official NSW nomination, but was soundly beaten in all events by Eric Hinton. Eric’s achievements were all the more meritorious because his own bikes were still in New Zealand and he resorted to a motley collection from the home Hinton stable. In the 250 race, he rode the old New Imperial-based special, the engine of which dated back to the mid-thirties, to an easy win over mainly local opposition. But Hinton really showed his brilliance in defeating Phillis in both the Junior and Senior TTs. Hinton’s Nortons were old long-strokers used by his famous father Harry and fitted with home-made full ‘dustbin’ fairings, while Phillis was aboard the latest short-stroke Manx Nortons that he had brought back from Europe at the end of his successful 1958 season. The streamlining worked, giving Eric speed on Phillis on the Flying Mile during the early part of the 350 race, before he pulled away to win by 20 seconds. The 500 race was much tighter, with Phillis glued to the back of the Hinton machine, the pair leaving West Australian Don Leadbetter behind. It would come down to the final Mountford Corner. After recording 135 mph through the speed trap on the Flying Mile for the last time, Phillis made a lunge under brakes. But Hinton was ready and in the scramble to the finishing line Phillis missed a gear and it was all over. Both men were credited with raising Geoff Duke’s lap record to 93.66 mph. Phillis did not start in the Unlimited TT which went Leadbetter’s way after Hinton retired with carburettor woes, while classy Victorian Jim Hocking easily won both Sidecar TTs. It was a grand meeting held in front of 30,000 spectators and cemented Longford’s claim as one of the fastest and most spectacular circuits in Australia.

Cars to the fore

The Australian Grand Prix was awarded to Longford in1960, and once again Eric Hinton showed he was the master of the roads, winning the 250, 350 and 500 classes with Bob Brown and Ron Miles filling the placings. Back in Australia for the first time in nearly a decade, Ken Kavanagh, on a works 125 Ducati was an easy winner in the Ultra Lightweight, while Jack Ahearn took out the Unlimited. The following year was a lower-key affair, with Ahearn the only name rider. He duly won the 500 and Unlimited, but retired when in the lead of the 350 after a footrest fell off, letting Victorian Bob West through for the win.

In 1962, seven-times world champion John Surtees was the star name at Longford, but in a Lola Formula One car, not on a motorcycle. He didn’t disappoint; winning the 90-mile car GP at an average speed of 110 mph, with a new outright lap record of 114 mph. Our own reigning world champion, Tom Phillis, was king of the bikes, taking out the 250, 350 and 500 races on the works 4-cylinder 250 Honda. He also hoisted the motorcycle lap record to 94.19 mph with his 2 minute 52 second lap. In fact, lap records were broken in every single solo class. No sidecar races were held. In winning the 125 TT, Honda-mounted Barry Smith took no less than 11 seconds off Ken Kavanagh’s 1960 mark. Phillis started his day with victory in the combined 125/250 event, where he saw off Mick Dillon’s TD-1A production Yamaha. The speed trap times from the Flying Mile told the story, with the Honda-4 clocked at 135 mph and Dillon only 109. At the presentation, Surtees opined that the 500-4 MV, his former factory mount, would easily top 150 mph on the Flying Mike and probably achieve a 100-plus lap.

World Champion Jim Redman was on tour in 1963, and Longford marked his first defeat on Australian soil. The Rhodesian easily won the 250 and 350 races on his 250 Honda-4, but was soundly beaten by Jack Ahearn’s 5-speed Norton in the Senior. The Lithgow-born veteran repeatedly smashed Phillis’ lap record, finally leaving it at 2.48.8 (95.43 mph) – just 6 seconds short of the magic 100 mph lap. Both Eric Hinton (500 Norton) and Arthur Pimm (1000 Vincent) also got well under the old record. Redman sat out the Unlimited, which also went Ahearn’s way. The meeting had a very international flavour, with Kiwi international John Hempleman winning the 125 event on a works Honda twin provided by Redman. The sidecar race saw an epic duel between Alec Corner, on Frank Sinclair’s famous Vincent, and former passenger Ray Foster’s kneeler Manx Norton. Foster’s 500 crossed the line first after magneto trouble slowed Corner.

The 2-day Longford meeting was now established as an annual favourite with riders from the mainland. All competitors were accommodated and fed at the grand Jesson Lodge, one kilometre from Longford’s town centre, the proprietors of which also served each rider a lunch from a large marquee in the pits. The local police obliged with an escort to allow competitors to ride their racing machines from the lodge to the pit area each day. Very civilized indeed.

Business as usual for Kel

1964 was the year that Kel Carruthers came, saw and conquered – winning every one of his five starts. The only other winners were John Bauskis, who rode his Honda to the 125 class victory in the combined 125/250 race, and Victorian Peter Highland who won the Unlimited B Grade race. Carruthers’ 250-4 Honda was in a class of its own in the 250 event, streaking away from local rider Ike Chenhall’s TD-1A Yamaha. In the 350 event Kel had 25 seconds in hand over Malcolm Stanton’s 350 Norton. Switching to his own 500 Norton, Carruthers was waltzing away with the Senior race until the strap securing the fuel tank broke, allowing the tank to slide forward under braking and jam the steering. Undeterred, he simply flattened his body over the tank and pressed on, once again leaving Stanton and Bill Pound in his wake. There was much muttering about the poor status of the bikes compared to the car events. Organisers declared there was insufficient space on the program to run sidecars and the solo races were crammed between car events. The inevitable question of circuit safety again arose when American Tim Mayer crashed his works Cooper Climax in the Tasman Cup race and was killed instantly.

The Australian TT title was once again awarded to Longford in 1965, and Carruthers was back. Once again the bikes were shoved around to suit the program, restricted for the first time to the Saturday only, and still sandwiched between car races. As a spectacle it probably left spectators bemused as well, with Carruthers simply disappearing into the distance to take a clean sweep of all five TT classes – the first time it had ever been achieved. Despite his domination, Kel never challenged Ahearn’s 1963 lap record, cruising to the 500 title over John Dodds and Ron Angel, then leading Keo Madden home in the Unlimited. Alec Corner romped away with the 4-lap Sidecar TT from Dennis Skinner. But a pall of gloom hung over the meeting when local Launceston rider, 25-year old Dennis Wing, crashed on the first lap of practice when his 350 Norton seized on the approach to King’s Bridge. The rider was thrown down the bank and into a steel post. Many of Wing’s Tasmanian MCC team-mates withdrew from the meeting as a mark of respect.

Last rites

The Yamaha Motor Company flew out one of their works RD56 250cc Yamahas for the early Australian races of 1966, and on March it was Longford’s turn to see the red and white missile, ridden by Allan Osborne. The meeting was titled the Australian Grand Prix, but drew only a mediocre entry. Electronic timing on the flying mile returned the astonishing and highly questionable speed of 164 mph (262 km/h) for Osborne as he cakewalked the 250 and 350 from Barry Smith’s Bultaco. He was heading for victory in the Senior 500cc GP when one cylinder went missing, letting Dick Reid’s Norton through to win from Bill Pound’s Norton and Smith’s remarkable little Bultaco. In the Unlimited GP, Bill Pound, mounted on the late Arthur Pimm’s Vincent Black Lightning, won from the Nortons of Ron Angel and Reid. Once again, Ahearn’s lap record stayed intact.

Although the cars soldiered on for two more years, 1966 would transpire to be the last hurrah for motorcycles at Longford. Today, the casual observer would hardly guess that Longford was once the annual mecca for motorsport run over a truly magnificent circuit. The meeting was a boon for local enterprise, with accommodation booked out for miles around and the Church cake stall doing record business on scones and tea. However the district still attracts a steady stream of visitors who clamber through the bush to inspect what’s left of the track. A compulsory stop is the Country Club Hotel, where a big collection of Longford memorabilia graces the wall, and a racing car pokes out the front window. Look up on the outside wall and you’ll see a mural depicting Stan Jones and his Maserati 250F in his victorious Australian GP of 1959. When the decision was made to obliterate the original network of roads making up the Longford lap, the constructors of the new highway gave scant regard to preserving history. The viaduct is still there, and you can scale the escarpment and walk under it and along a kilometre of the original track that led to the Kings Bridge. The bridge is long gone, but standing at the water’s edge you can imagine what it must have been like to take this section, flat as a maggot, bouncing and leaping over the corrugations. Newry Corner still exists, as does a section of the road leading off Long Bridge, but a power sub-station has been planted smack in the middle of what used to be the braking area. And the Flying Mile is completely intact. Tuck your chin down on the tank at the regulation 80 kph speed limit and picture what it must have been like to have a 500 Manx engine spinning to 8,000 under you as you rocketed past the sleepy property gates on either side. Any trip to Tassie must include a visit to Longford – the big daddy of the Australian road circuits.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photographs: Charles Rice, Keith Ward, Rob Sayward