From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 91 – first published in 2020.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook with assistance from Graeme Staples • Photos: Phil Ainsley, Graeme Staples, John Ford, Lloyd Williams.

The Kiwis have a reputation for home-spun engineering that rivals, or betters, anything anywhere. And this is never more apparent than in the monocoque racers created by Steve Roberts.

The term Monocoque comes from the Latin for single (mono) and the Gaelic for shell (coque). It is commonly used to describe a construction technique that supports a structural load by using an object’s external skin as opposed to using an internal frame or truss that is then covered with a non-load-bearing skin. Monocoque construction was first widely used in aircraft in the 1930s. The technique took over Formula One in the ‘sixties and soon after appeared in motorcycle GP racing, in the form of the 250cc OSSA ridden by Santiago Herrero, and the 500cc SMAC built by Frenchman Eric Offenstadt.

Fresh thinking

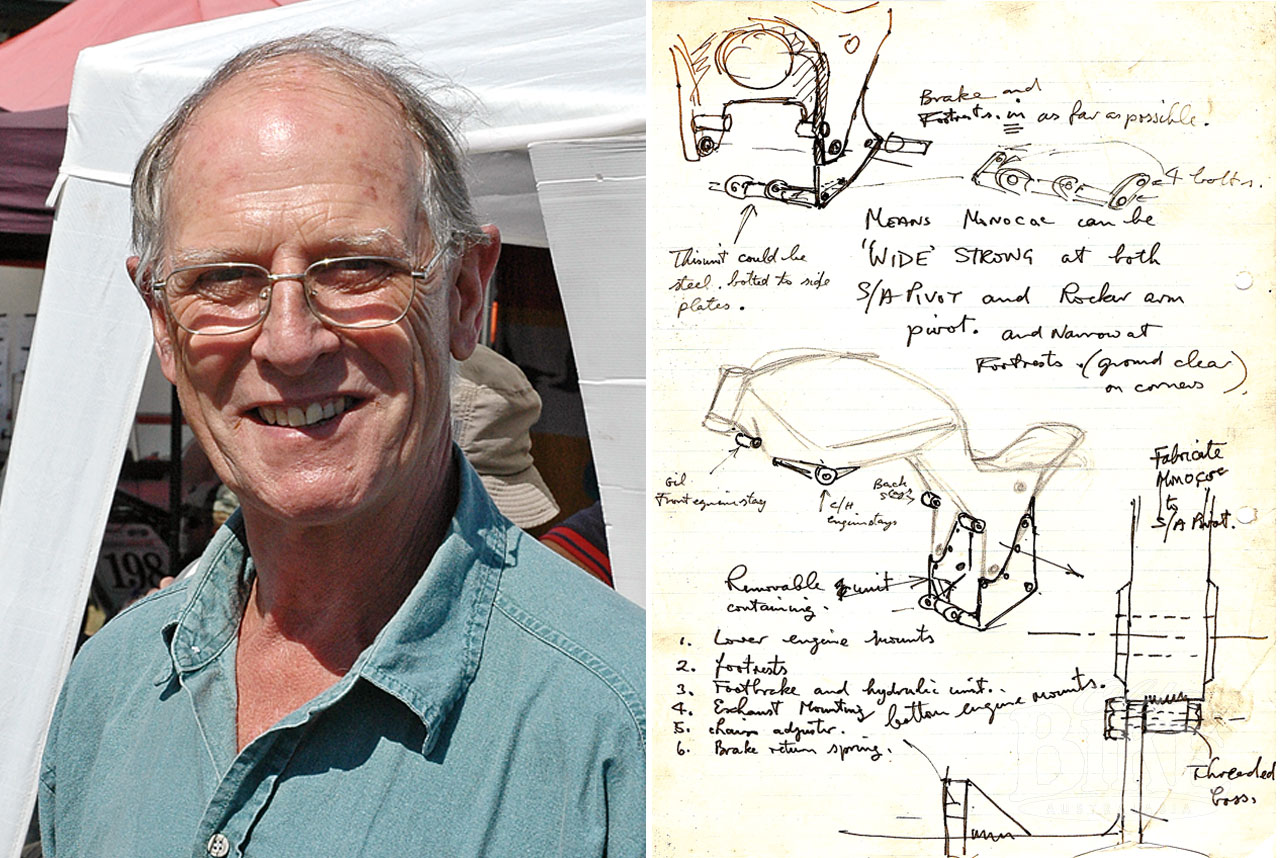

Quite a few years back I had the pleasure of interviewing the legendary Steve Roberts in New Zealand. Steve is a man who is absolutely devoid of airs and graces; what you see is what you get. He is also arguably one of the most innovative and influential motorcycle design engineers ever, although he modestly says, “I’m just a tin basher”, referring to his original training as a panel beater. Yeah, right, like Michelangelo was a plasterer.

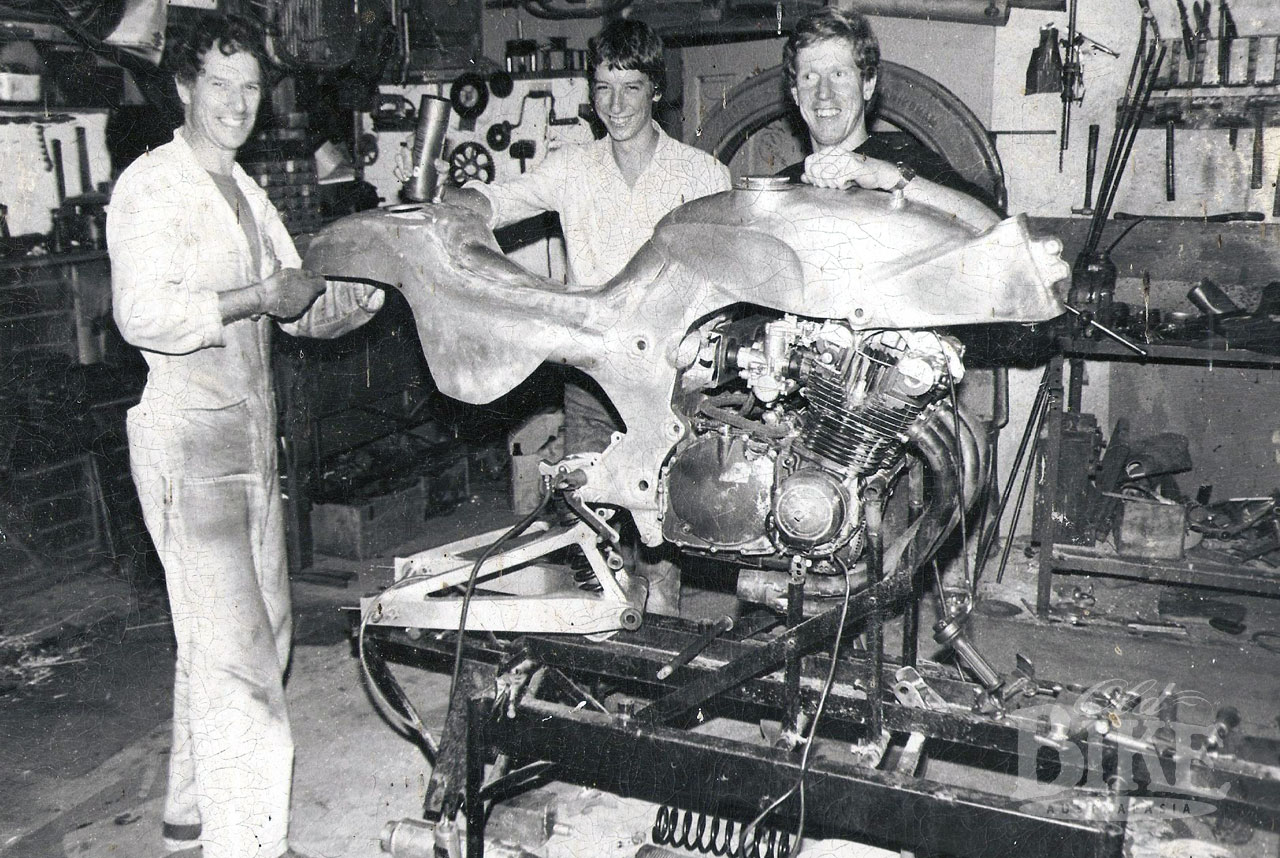

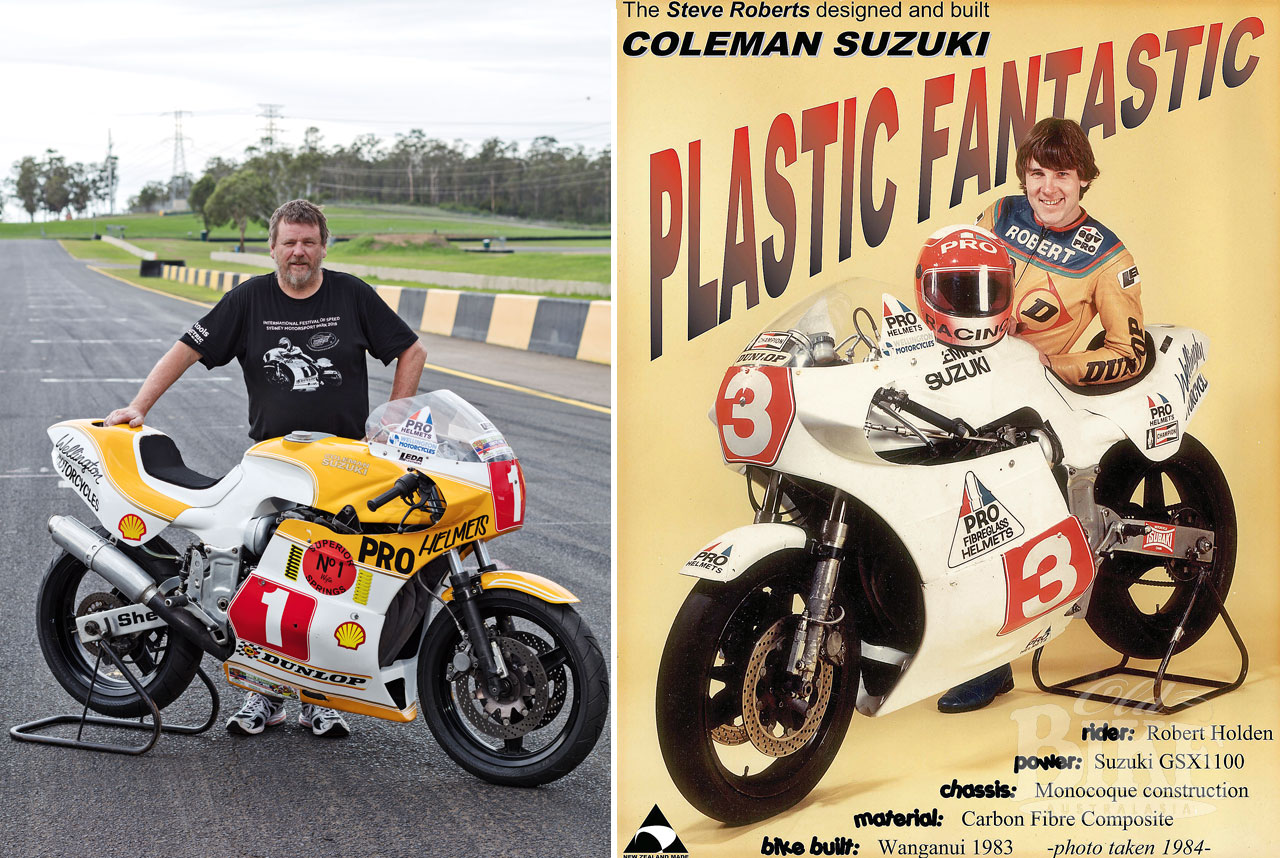

The creations that have emerged from Steve’s humble workshop/shed near Wanganui are many and varied; all manner of motorcycles, priceless racing cars, and things that fit into other categories. Many of these were the result of input and finance from Coleman’s, the long-time NZ Suzuki importer. One of the most famous and significant is the motorcycle (or motorcycles, there were three built) known as the Plastic Fantastic – the Suzuki-engined Kevlar monocoque TTF1 machine raced by the likes of Dave Hiscock, Robert Holden, Norris Farrow and others. Steve told me that when he first floated the idea several riders rubbished the concept. His answer was, “You wear a carbon fibre helmet. Would you rather wear an aluminium one?” He added, “At the time, the police had just been issued with bullet-proofed vests using Kevlar, and I thought – if it can stop a bullet, that’s for us.”

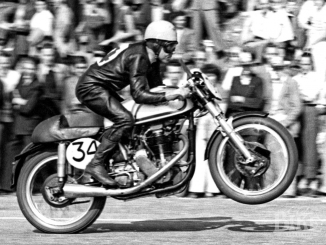

Monocoque construction was something that had interested Steve for some time. In 1967 he built a motocross bike largely from fibreglass, and in 1972 produced an aluminium monocoque to take a TR500 Suzuki engine which Keith Turner, who had finished second in the 1971 500cc World Championship, intended to use for the 1972 championship. The new machine was ready for the Singapore Grand Prix, and although it handled superbly, the big air-cooled two stroke twin engine overheated badly as a result of being enclosed by the chassis. While Turner went back to his 1971 machine (which featured a Roberts-built steel tube frame), the monocoque TR500 was taken to USA for ‘development’ but soon vanished. A few years later, he built a sheet steel monocoque chopper with a Suzuki GS1000 engine for a customer.

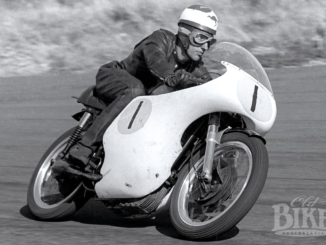

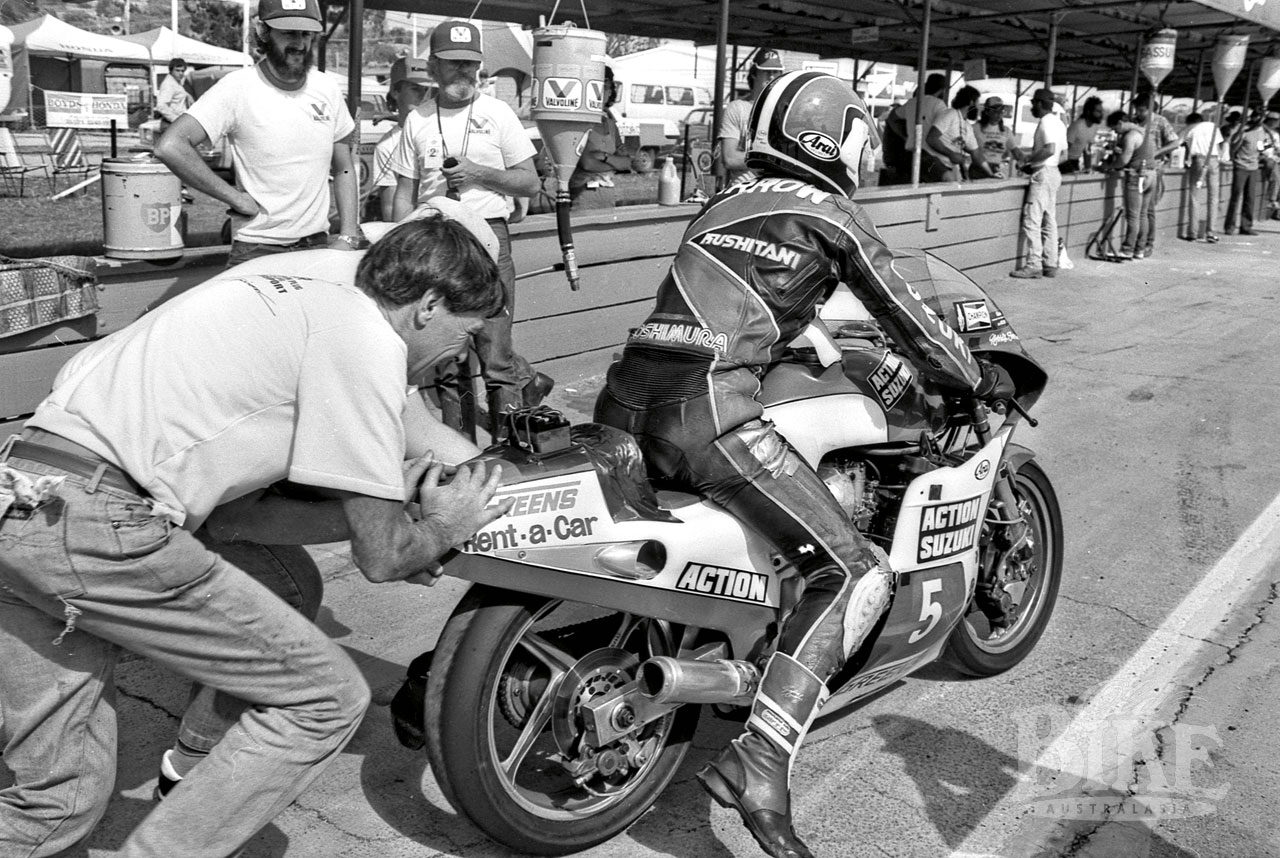

Steve was still very keen on the concept, and later began work on a scaled-up version to house a Suzuki GS1000R engine, the chassis constructed from hand-beaten 3mm aluminium. This became the machine that Dave Hiscock took to Britain in 1982, primarily to contest the TT. He finished an excellent third in the TTF1 race (behind only the works Hondas of Ron Haslam and Joey Dunlop) that opened the TT week, and followed this up with ninth place in the final event, the Classic TT. Later in the year Hiscock brought the aluminium bike to Australia to contest the Swann Insurance International Series, which he won convincingly, despite not finishing in the opening round.

Something that Steve had learned from working on the locally-built Leda Formula 5000 and Can Am cars which Graeme McRae drove with great success was not just how aluminium monocoques worked and needed to be designed, but the process of using pressurised air to increase performance. McCrae told Steve that it was vital to enclose the carbs and get equal pressure to the carbs and the fuel tank. “We couldn’t do that with normal ducting, so I decided to take the air from the back of the rider – there is an area of high pressure created there – and ram it into the air-box. None of the TTF1 bikes had air-boxes – open carbs with bell-mouths was thought to be the way to go then – but when we got this working Dave was really excited. He said it was worth at least five horsepower.”

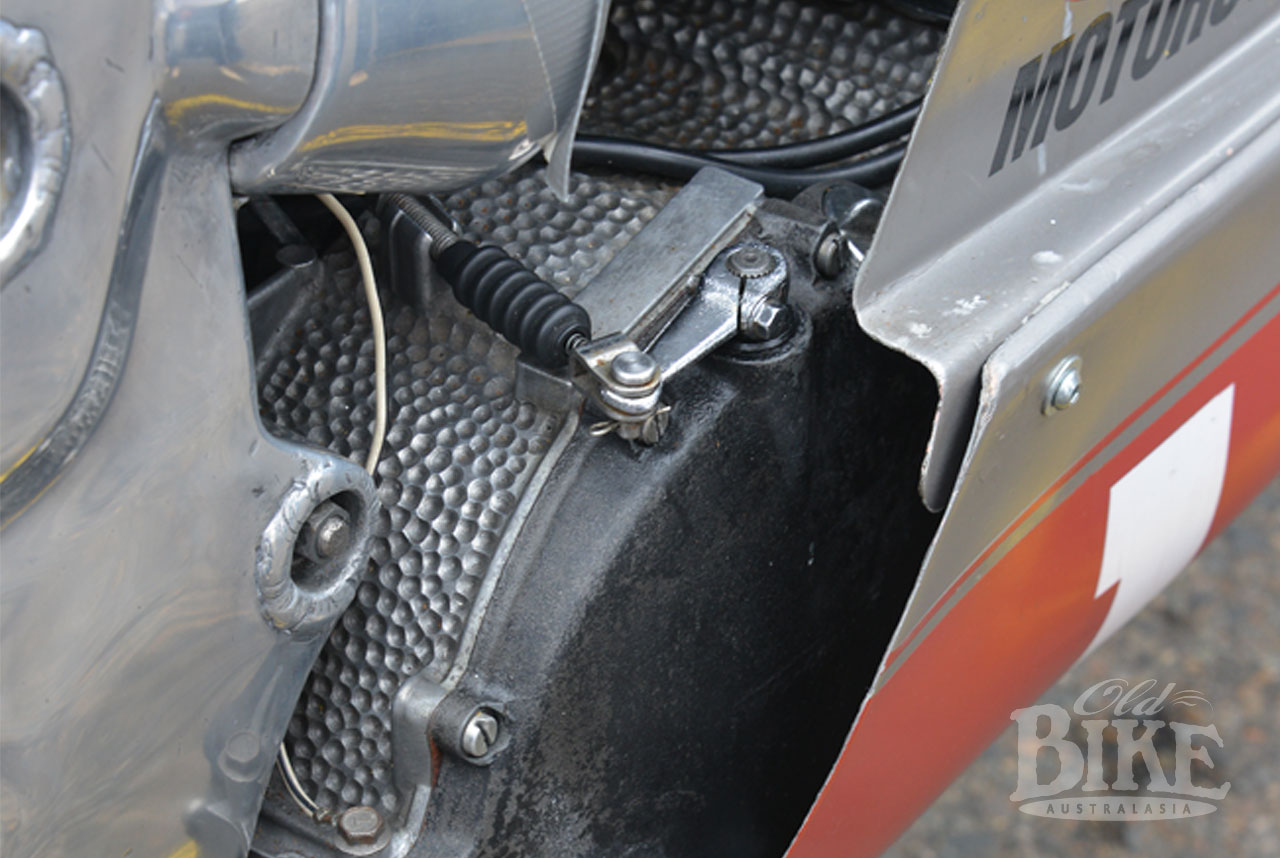

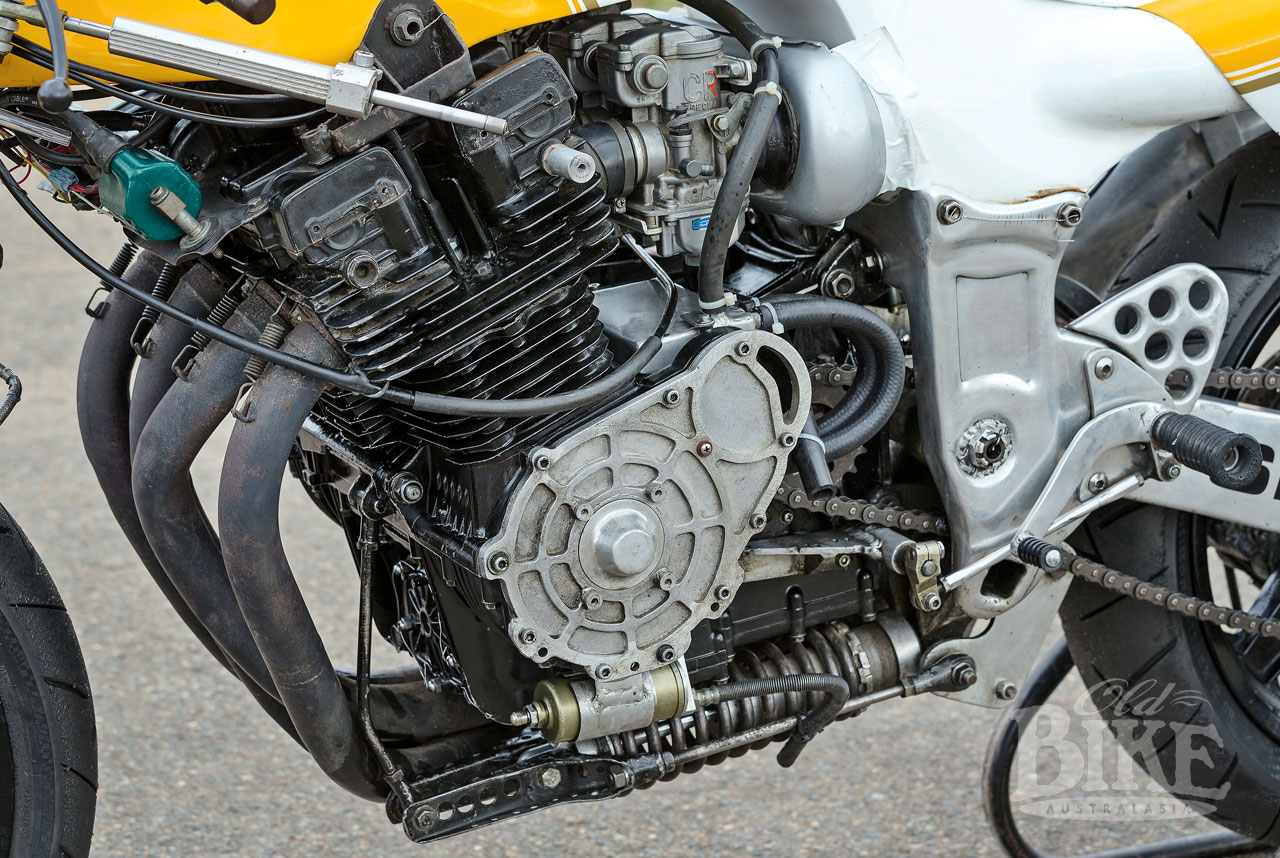

Steve was well aware that aluminium fatigues over time, so the decision was made to use the alloy chassis as a dimensional model for a brand new chassis made from Kevlar. The concept for the revolutionary new machine, quickly dubbed the Plastic Fantastic, was born. “I began experimenting with carbon fibre and Kevlar. When you hit the carbon fibre with a hammer it would just shatter, but the Kevlar stayed intact. I used carbon fibre at places for bearings because you can machine it.” One of the problems on the aluminium bike was that the rear shock, positioned behind the engine, overheated when the oil got hot. “Dave came up with the idea to put the shock underneath the engine with the exhaust pipe running alongside,” says Steve, who christened the system ‘Tension Suspension’, since the shock worked in the opposite way to the usual practice, with linkages running back to the alloy swing arm. “We also ducted air in there to keep it cool. Moving the shock gave us more space for the tank”. Because the ‘chassis’ for the machine (the entire front end and fuel tank/backbone section) was so easy to detach, Roberts and Hiscock even envisaged having separate wet and dry weather configurations, with different head angles.

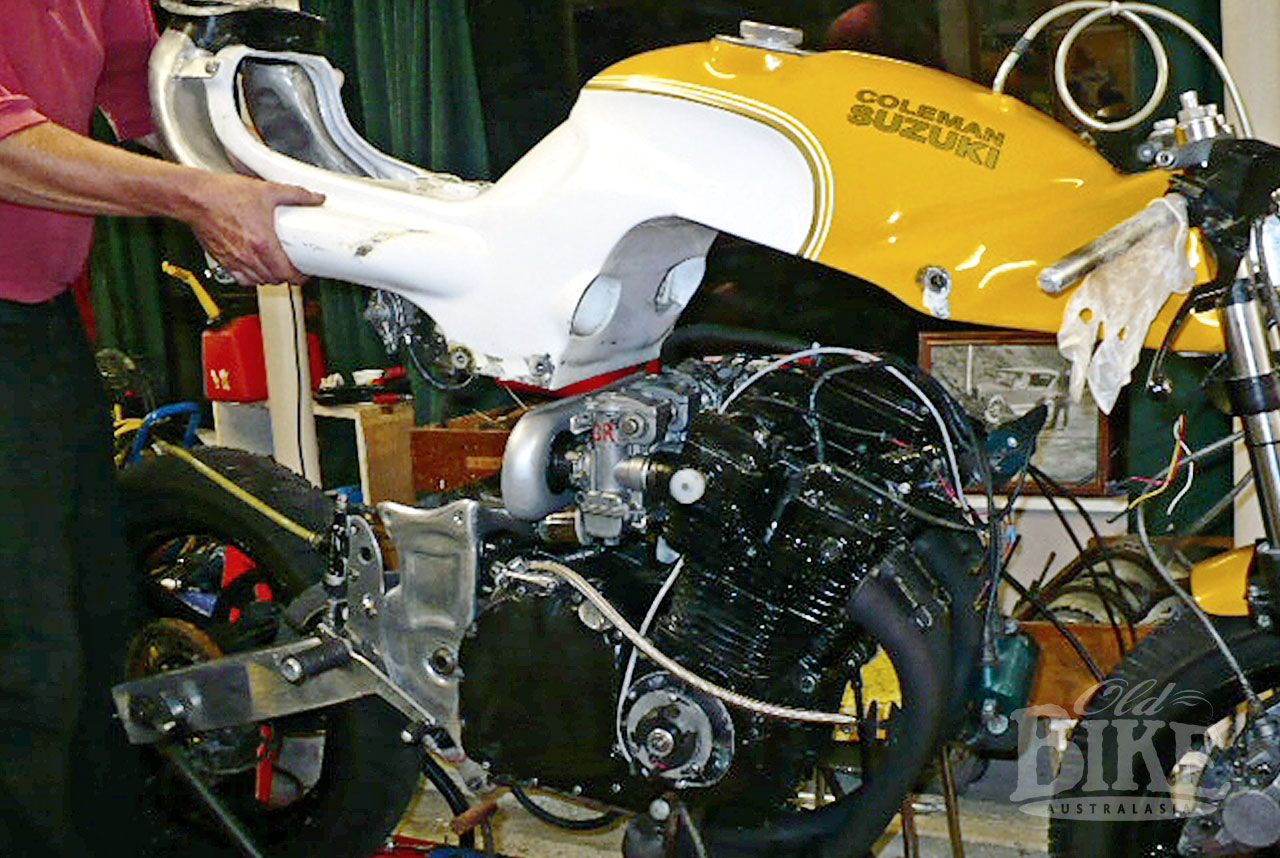

A prototype of the Kevlar bike came together remarkably quickly, and by early 1983, it was ready for shakedown tests, using the engine and some parts from the aluminium bike in the new chassis. The shakedowns were encouraging and Roberts set to work to build a completely new Kevlar machine, officially the latest of the Coleman Suzukis but always known as the Plastic Fantastic.

The aim once again was to have the bike ready for the Isle of Man, and the rolling chassis was dispatched to Britain where it was fitted with a new Yoshimura GSX1000 four-valve engine. Time was tight, but the Plastic Fantastic was ready for the TT, where Hiscock took it to 8th place in the TTF1 race. Later in the week he was running strongly in the Classic TT until the engine destroyed a piston.

Engine problems plagued the season, and when the engine locked up at Assen, Dave was thrown heavily while the bike executed barrel rolls, discarding bits along the way. It looked a mess, and Dave suffered serious injuries to his knees, but the monocoque stayed straight, vindicating Steve’s theories.

Back in New Zealand for the year-ending International Series, Hiscock took out the Bryan Scobie Memorial Trophy at Wanganui and cleaned up at Gracefield to wrap up the series. Robert Holden thereafter took over riding duties, winning the New Zealand Championship for the 1983/84 season and eventually purchasing the machine from Colemans. Although Holden won the 1984 Brut 33 Series, the engine, a fairly standard GSX1100 which had replaced the Yoshimura unit, became increasingly unreliable. It was brought to Australia in 1985 to contest the Arai 5oo at Bathurst, where Holden was to have teamed with Rob Phillis, but the engine blew up in practice and the team non-started. That was to be the Plastic’s swan-song, an ignominious end to a promising beginning.

A further Kevlar bike had been built by Roberts during 1984 to be raced by Norris Farrow, with the Kevlar chassis slightly redesigned to provide additional strength in certain sections. Farrow scored a notable win at the Penang Grand Prix in 1985, and also came to Bathurst in the same year, where he scored a commendable third place in the feature race, the Bathurst Centenary Grand Prix. In this race, which was marred by crashes to front runners John Pace and Rodger Freeth, Holden again suffered engine failure, Farrow avoided the incidents and came home behind winner Mike Dowson and Malcolm Campbell. However Farrow’s subsequent season was also marred by repeated engine failures, and the third of the Roberts Kevlar bikes (after the prototype and the Hiscock model) was sold to Kiwi Blair Briggs, who eventually moved to Australia and brought the bike with him which he still owns.

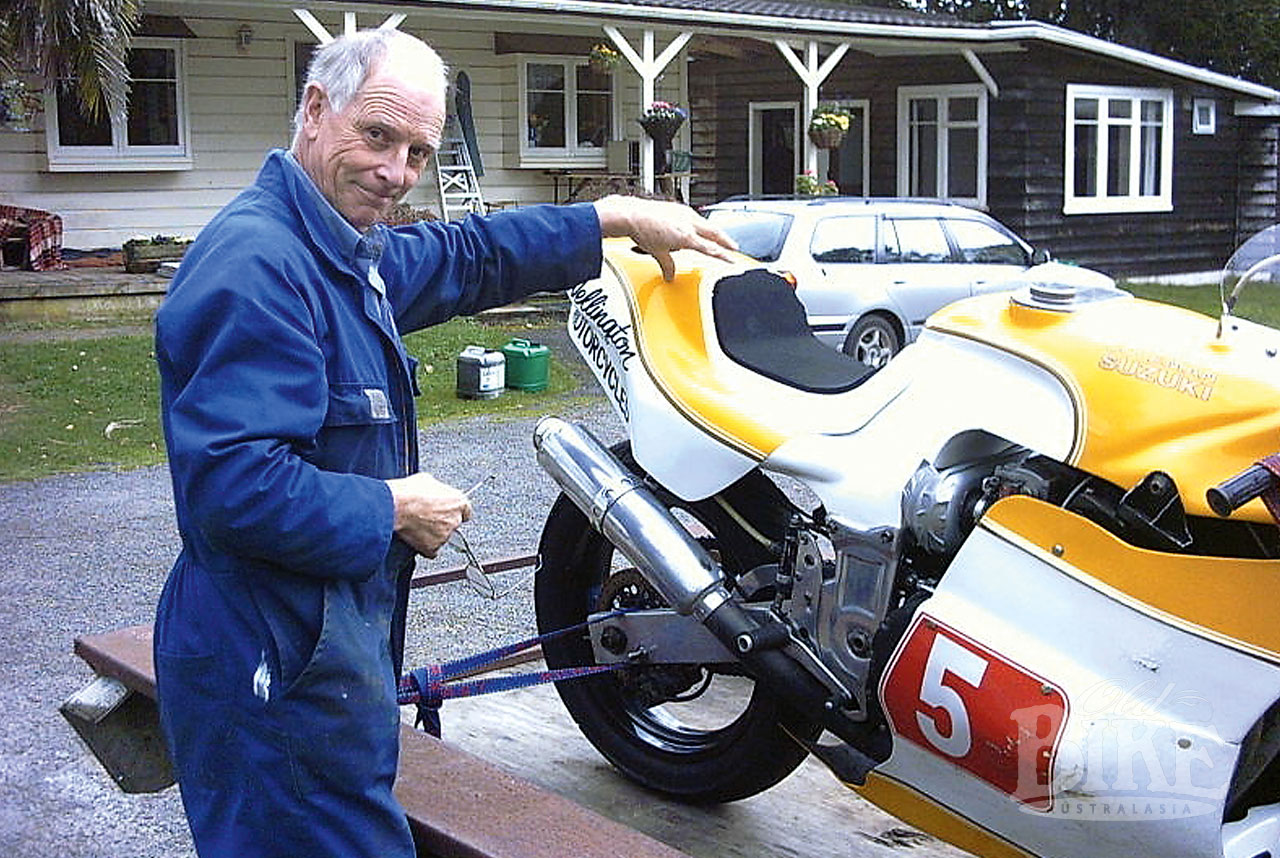

The ex-Hiscock Plastic, for which Roberts received a 1983 Inventors Award in New Zealand, was sold to Wellington enthusiast Graeme ‘Spyda’ Staples, who had become enamoured of Roberts’ work when he acted as passenger in Andy Kippen’s Kawasaki outfit which featured a Roberts monocoque. The team won three New Zealand Championships on the outfit.

Which brings us to the current day, or actually March 2018 when Spyda brought the Plastic to Sydney Motor Sport Park for the Festival of Speed, where significantly, it rubbed shoulders with the aluminium bike for the first time in many moons. I already had a pretty full dance card, with guest spots in the demonstration sessions to reacquaint myself with the NCR Ducati F1 that I raced in the 1978 Isle of Man TT, plus a run on the chain-drive Yamaha XS1100 which the late Greg Pretty took to three wins from three starts in 1981 Superbike competition. But when Spyda offered me the opportunity to ride the gleaming yellow Plastic Fantastic in the final session on Sunday, I grabbed the chance with both hands. I had heard so much about this motorcycle, and seen it demonstrated by Dave Cole at Pukehole ten years previously, but here was a chance to ride it for real.

Just getting to the bike was the first challenge. All weekend, the Plastic and the sister aluminium bike had been surrounded by eager onlookers. After all, on this side of the Tasman, the last real glimpse had been Dave Hiscock in the 82 and 83 Swann Series and Norris Farrow at Bathurst 85. And as an added bonus, Blair Briggs had brought along the Farrow machine, generally known as Mk2 even though it is the third of the three built, and had demonstrated it enthusiastically over the weekend.

For me, the trio of mounts to be ridden could not have been more different. The rangy Ducati, with its chopper-like steering geometry and relatively gentle power, was an armchair ride, and on very old tyres, a fairly cautious one. Then the XS1100, a rortin’ snortin’ big lump of a thing that twisted and leaped like a cornered polecat, yet behaved itself once you learned to relax a bit. And boy it was fast. Then came the Plastic, undoubtedly the most sophisticated of the lot.

Power-wise, the Plastic had enough steam to be very competitive, but with the fragile engine, seldom was. I think the motor as it stands is now in a fairly placid state of tune in the interests of rideability and reliability, but it revved freely and had plenty of poke. The machine’s true forte however is the handling, which, as I said, is in a different league to the Ducati and the Yamaha. On this occasion, the bike was shod with Continental Road Attack tyres, still 18 inch at each end, which are probably better than the race tyres it originally wore nearly 40 years ago. The Plastic steers beautifully which would have been a major asset at the Isle of Man and made for a very pleasant and precise ride at SMSP, which is mainly tightish corners separated by an overly long main straight. Being able to tip the bike into the turns and have it hold its line (the line you want), and not get all snarly as the power is applied exiting the turn is where time is made up and energy conserved. I didn’t think the brakes were anything spectacular, but then again, they are 40 years old.

At one point I could see Blair Briggs just ahead on the blue Plastic and thought there may be an opportunity for a bit of fun with both bikes circulating together, but just at that moment, his version decided it had had enough for the weekend and ceased operation. All too soon the outing was over and I reluctantly returned the bike to Spyda, who seemed very happy to have it back in one piece. It was a fantastic experience and simply reinforced my belief in what Rod Coleman had said to me years ago about Steve Roberts’ work, “The man is a genius, nothing less.”