From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 98 – first published in 2022.

Story Rennie and Jim Scaysbrook • Photos Russ Murray and Yamaha-Motor Australia.

There was something funny going on in the mid ‘eighties, bike-wise that is. It was okay for small shops and home tuners to build mega-monster bikes with car engines, multiple turbocharges, nitrous oxide injection and all sorts of other demon tweaks, but a conservative major Japanese manufacturer?

To be fair, all the Japanese companies were testing the water with outsized offerings around this time. Suzuki had the GV1200GL, an 82-degree 1165cc V-4 sold as the Madura in USA. Kawasaki’s entry was the ZL900 Eliminator, a transverse four of 908cc, while Honda’s entry was the VF1100C Magna, another V-4 with 90-degree angle between the cylinders. And then there was the V-max, the most expensive of the quartet by quite some margin ($5299 in USA, 1986), the only one with a five instead of six-speed gearbox, and the meanest and most powerful of the lot.

Yamaha didn’t exactly start with a clean sheet of paper when the V-max was conceived. It had the Venture, a very Harleyesque cruiser that appeared in 1983 using an all-new 1198cc water-cooled 70º V4 engine. Its full title was the Yamaha Venture Royale, and complete with the luggage suite, fairing, massive lights, crash bars and assorted bling, it just crept under the 400kg mark when ready to ride away. In Royale form, the engine poked out an adequate 90 bhp, but more grunt, a lot more, was in the V-max terms of reference.

The V-max concept had its genesis from a fact-finding and trend-studying mission to the USA undertaken by a group of Yamaha engineers, including Akira Araki, who would become the head man on the V-max project.

The Venture engine underwent a severe program of weight loss and power mods. Lighter pistons, slimmer stems for the 16 valves (which had larger heads), enhanced air flow through to the combustion chambers, stronger crank and rods, were all aspects of the V-max package that saw peak revs shoot from 7500 on the Venture to 9500. The four camshafts were modified with increased dwell and lift and the rejig saw power skyrocket from 90 bhp to 143. The standard 5-speed gearbox was largely untouched, a beefed-up diaphragm clutch employed, but the shaft final drive was strengthened to cope with the 60% increase in power. Unlike its competitors in the merging mega-cruiser segment of the mid-eighties, the V-max used a counterbalance to smooth out primary imbalance.

Boosting the beast

However despite all the internal work, Yamaha’s engineers were still dissatisfied with the power output for their new flagship and went back to the drawing board. What transpired was christened the “V-Boost system”. This involved connecting the manifolds leading from the four 35mm Mikuni CV carbs to the inlet tracts on each bank of cylinders, with a central butterfly valve that operated via a servo motor itself triggered by the ignition. When the engine reached 6,000 rpm, the servo kicked in to progressively open the valve, reaching the fully open point at 8,000 rpm. It meant that each cylinder was now being fed simultaneously, which had the effect of vastly increasing the flow of fuel mixture at higher rpm, similar to a supercharger. It also retained the milder state of tune below 6,000 rpm, ensuring excellent low-speed response and tractability.

The V-Boost wasn’t for everyone however. In Britain (where the V-max went on sale in 1991) and parts of Europe, the voluntary 100 horsepower limit meant the system was disabled, dropping power to much the same levels as it had been in the Venture Royale, which meant buyers stayed away in droves.

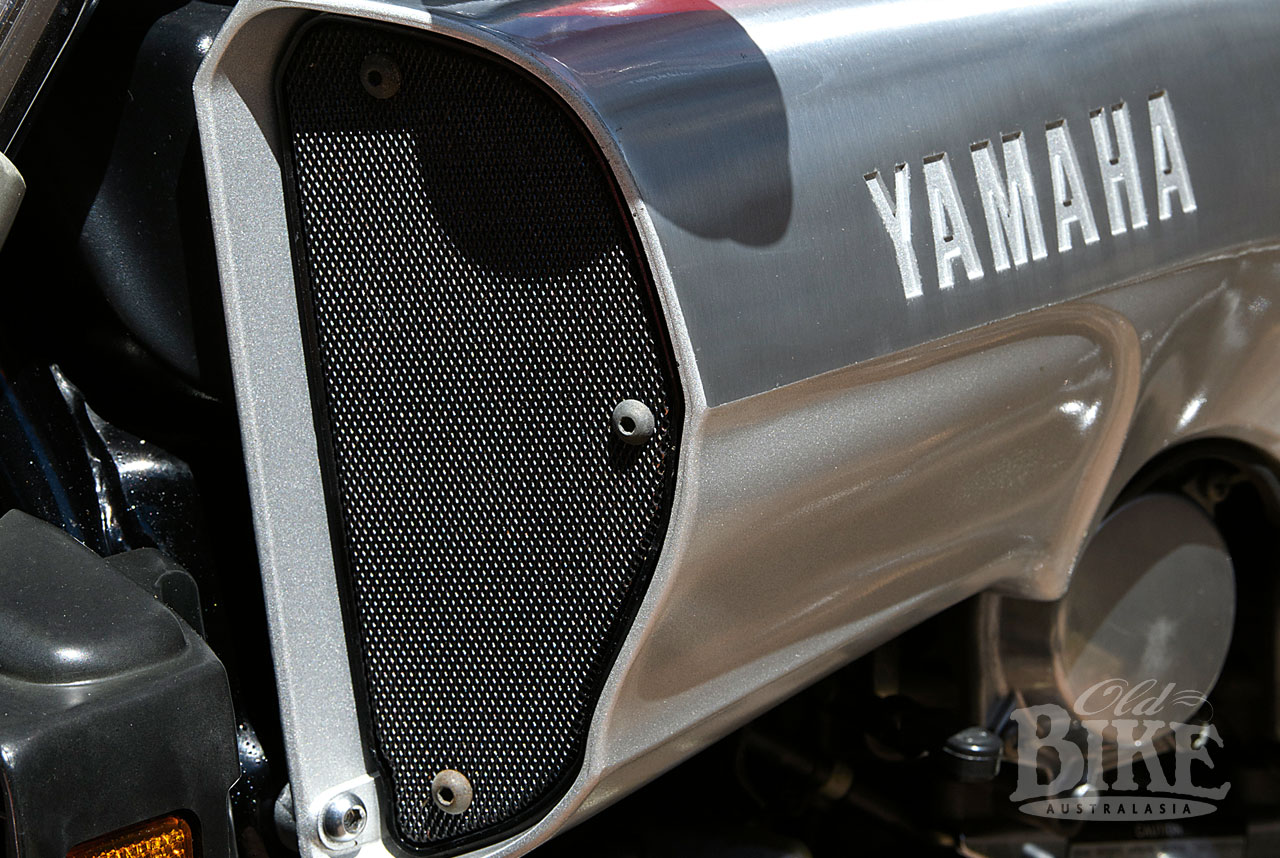

Reaching that 6,000 rpm kick-in was basically experienced through the seat of the pants, because the tacho was for some unfathomable reason not positioned where it logically should have been – beside the speedo above the headlight – but ensconced in a small panel let into what looked like the petrol tank (but wasn’t, it’s under the seat) alongside the stack of warning lights. So keeping an eye on the revs was almost impossible, particularly when the V-Max was launching towards terminal velocity. The faux fuel tank was accompanied by what looked like air scoops on each side, but actually were just for decoration. The air for the carbs actually came via ducts underneath the dummy tank. With the carbs sitting neatly in the vee of the engine (along with the ample airbox), there was ample space in the mid section, so that’s where the fuel tank went, along with the battery.

Chassis-wise, the V-max was reasonably conventional, although understandably beefy and, thanks to the 1590mm wheelbase, long. The 40mm Kayaba front forks were also long, kicking up the front end of the bike, and making the ultra low seat (just 760mm off the ground) seem even lower. Still, with 29º rake and 119mm trail, the front-end dimensions produced reasonably acceptable steering. To assist this stability, the tubular steel frame was heavily gusseted around the steering head.

Road manners

Early road tests criticised the paucity of the seat padding which made long stints in the saddle rather painful, and much head scratching surrounded the aforementioned positioning of the tacho. Surprisingly, most testers reckoned the V-max handled reasonably well, up to the limits of the ground clearance which saw things scraping as soon as any inspired cornering took place. To maximise the ground clearance, Yamaha went for stiff springing and firm damping, and although this sharpened the handling, it also made for a fairly rough ride, especially on the US freeways with expansion joints in the concrete surface. A legitimate concern was the fuel range – barely 150 km between stops thanks to the 15 litre fuel tank. When the low-fuel warning light in the secondary instrument popped on, reserve was engaged via a thumb-operated switch on the right handlebar. The riding position too was not overly popular; a common complaint was that the footrests were too high and to far forward.

Despite their hefty appearance, the front brakes were not really up to the job, that job being to haul down around 280kg of mean motorcycle. But it sure was fast; sub-eleven second standing quarter miles were racked up with ease in a US test, with terminal speeds around 125mph (200km/h). That meant the V-max was almost reaching its stated top speed of 217km/h in just 440 yards. Score ten points for acceleration.

Obviously the V-max was aimed directly at the US market, and the timing was not exactly ideal. By the middle of the 1980s, the country was hovering on the brink of recession, and motorcycle sales had dropped drastically. So much so, that because of the rash of ’86 models still languishing in showrooms, Yamaha made the decision to suspend production of the V-Max in 1987. But while this may have looked like the death-knell for the big bruiser, it rose again in 1988, with few changes other than new wheels. In following years, a digital electronic ignition system was added, a few minor chassis changes in 1993, and at last, larger 43mm fork tubes to combat the front end flex that had been synonymous with the model. Front brakes went to 4-piston calipers, and the electrical output was ramped up.

Hold your horses

Out in the colonies, there was much hysteria when the V-max was announced, but seven long years passed before it finally hit our showrooms. Yamaha Australia had dodged questions about the V-max for ages, probably hoping that it would just go away. It was, after all, a politically incorrect motorcycle with its stupendous power, eye-watering acceleration, and insatiable appetite for fuel and rear tyres, at a time when going green was starting to catch on. But while Yamaha Australia steadfastly refused to add the V-max to its local offerings, one of its leading dealers had other ideas. Sole distributors for the brand in South Australia and Northern Territory, Pitmans was a family-owned outfit that had its own ideas on selling motorcycles. Pitmans had imported a single V-max to display on their stand at the 1987 Adelaide International Motor Show (along with a Ventura Royale). The reaction was extremely positive, but as the V-max had no Australian compliance, the next step was anything but simple. It took 18 months and a considerable amount of cash before the ADR (Australian Design Rule) number was issued. This led to a small but consistent supply of the V-max, all imported directly by Pitmans. Thankfully, all thoughts of importing the dumbed-down Euro 100ps model were quashed, and what we got was the full-nine-yards 145hp job.

By 1992, the model was in stock, at least in the landmark Pitmans showroom in Athol, South Australia, with a price tag of $15,500, plus freight to dealers outside of SA. With seven years of existence behind it, there was even a healthy range of after market gear including, would you believe it, a big-bore kit with new sleeves and 86mm pistons that pushed power beyond 160hp. There were also replacement wheels to accept the more fashionable and practical 17-inch tyres that were becoming standardised and which had seen development of odd sizes (like the original 15 inch rear) stagnate.

Parental control

When Pitmans relinquished the distribution of Yamaha in South Australia to Yamaha-Motor Australia, the Japanese company also inherited the ADR-compliance V-max. Little had changed, save for larger 300mm front discs which were gripped by four-piston calipers, while fork tubes had increased to 43mm. By this stage the price had crept up to AUD$16,950 but Y-MA decided to drop it back to the original $15,500.

Then in 2007 came the announcement that the V-Max was to cease production forthwith, which was partially true. In fact, it marked the end for the 1198cc V-Max, and the beginning (in 2009) for the VMAX (no apostrophe) – a 1700cc (actually 1679cc) fuel-injected 190hp, 310kg behemoth capable of 273 km/h that arrived with a bang and departed with a whimper. With 163Nm of torque, it’s no wonder a five-speed gearbox was considered entirely adequate. While the 1700 was sold up till 2020, production actually ceased in late 2017, with sales never having achieved anything like forecasts. The price tag of $31,299 plus ORC may have had something to do with the lack of mass appeal. With these poor figures, plus the need to substantially revamp the VMAX to meet Euro 5 Compliance, the time had come to say sayonara.

Our featured V-max is a 1995 model, produced about halfway through the big bruiser’s production run. Owner Nick McGinn says, “l’d sold a bike and was looking at getting something to replace it. After months of contemplating what to get, l remember looking at a V-max at Clipstone Yamaha in the late ‘80s. So that was it. I purchased mine in March 2017 from a shop in Bairnsdale; a nice original untouched one. I picked it up for $5,000. It’s a lot of bike for the money. I looked around for a few months before settling on this one as it is completely original. I like unusual bikes and it fits the criteria perfectly. I’m the third owner and have covered 13,000 trouble-free km in nearly five years. Loads of fun and it draws a crowd where ever you park it.”

Specifications: 1995 Yamaha VMX12N V-max

ENGINE: 70-degree-four, dual chain-driven overhead camshafts, 4 valves per cylinder.

BORE X STROKE: 76.0mm x 66.0mm

DISPLACEMENT: 1198cc

COMP. RATIO: 10.5:1

COOLING: Liquid.

CARBURATION: 4 x Mikuni BDS35

IGNITION: CDI

LUBRICATION: Wet sump

TRANSMISSION: 5-speed, wet clutch, shaft final drive.

FRAME: Twin downtube, full cradle frame with steel swing arm.

WHEELBASE: 1590mm

SEAT HEIGHT: 765mm

SUSPENSION: Front: Kayaba Air-adjustable front fork with 40mm tubes. 140mm travel. Rear: Kayaba Twin shock absorbers, adjustable spring preload and rebound damping. 100mm travel.

BRAKES: Front: 2 x 298mm discs with 2-piston calipers. Rear: 1 x 282mm disc with 2-piston caliper.

TYRES: Front: 110/80 V18. Rear: 150/90 V15.

FUEL CAPACITY: 15 litres

DRY WEIGHT: 262kg

PRICE: $15,500 (Australia, 1992)