From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 82 – first published in 2019.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Des Lewis and OBA archives.

Is it really twenty-five years since the GSX1300R (also known as the Hayabusa, after the fearless dive-bombing bird of Japan) smashed through the speed barriers to become the fastest-ever production motorcycle? To achieve this, the ‘Busa’ had to unseat another feathered foe, Honda’s CBR1100XX ‘Blackbird’, which hitherto had narrowly held that mantle.

Interestingly, its name was also a clever play on words by Suzuki as, apart from being the fastest bird in the world, the “Hayabusa” Peregrine Falcon also preys on other birds – including Blackbirds. The new Suzuki could be had for $17,490 at the time of its Australian release, or $491 more than the Honda Blackbird.

In terms of sheer presence, the Suzuki broke new ground, abandoning the current trends for a shape (and décor) that was as controversial as it was functional. Colour options for the original Gen 1 model were the Copper brown and silver that came to define the model, red and black, or grey and black.

Strip scorcher

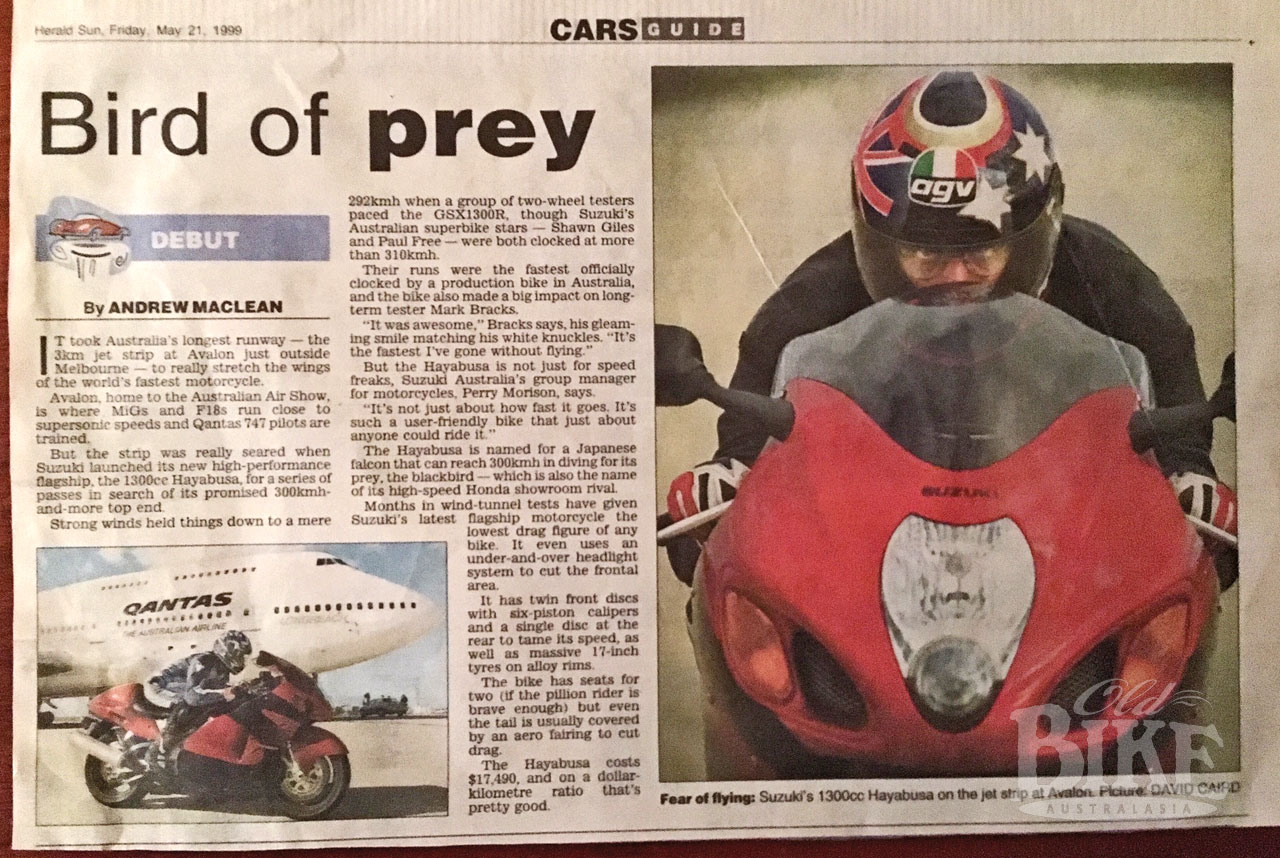

Launched locally at Avalon Airport in Victoria in June 1999, the experience had journalists scrabbling for superlatives. It was not just the outright, mind-warping top speed, which saw the Suzuki scream past the magical 300 km/h mark, but the complete performance package that had been achieved by meticulous attention to aerodynamics. Head of Suzuki Australia at the time, Perry Morison, recalls the event. “I had taken a couple of local journos – the late Ken Wootton and the late Jeremy Bowdler – to Spain for the international launch which was a great event, but I wanted to do something locally that would be different and respect the nature of the bike. Along with a contingent of Australian journos, I went on a ride to Lorne on the Great Ocean Road, but I didn’t tell them what we had planned next. We hired Avalon Airport and the police manned the radar speed equipment, and we produced a special Certificate of Speed for each journalist as they had their runs. Sean Giles and Paul Free, who were our Superbike team riders at the time, had been there the week before and clocked over 310 km/h, but on the media day there was a strong cross wind which made things pretty tricky. As I recall, Mark Bracks was the fastest of the journos at something like 292 km/h.”

Bracks himself has fond memories of the day at Avalon. “The cross wind was so strong that I was banked at about 15 degrees to counter it. The police had their radar set up about halfway down the strip to leave plenty of room for braking, but the Suzuki was still accelerating at that point. After the police packed up and left, a few of us went out again and kept the throttle open way past where they had been and the top speed would have been heaps faster. After my last run Gilesy and Paul Free asked me where the tacho needle had been (no point looking at the speedo which was not accurate) and I said it was off the clock. They said, “OK that’s what we have to aim for!”

Cheating the breeze

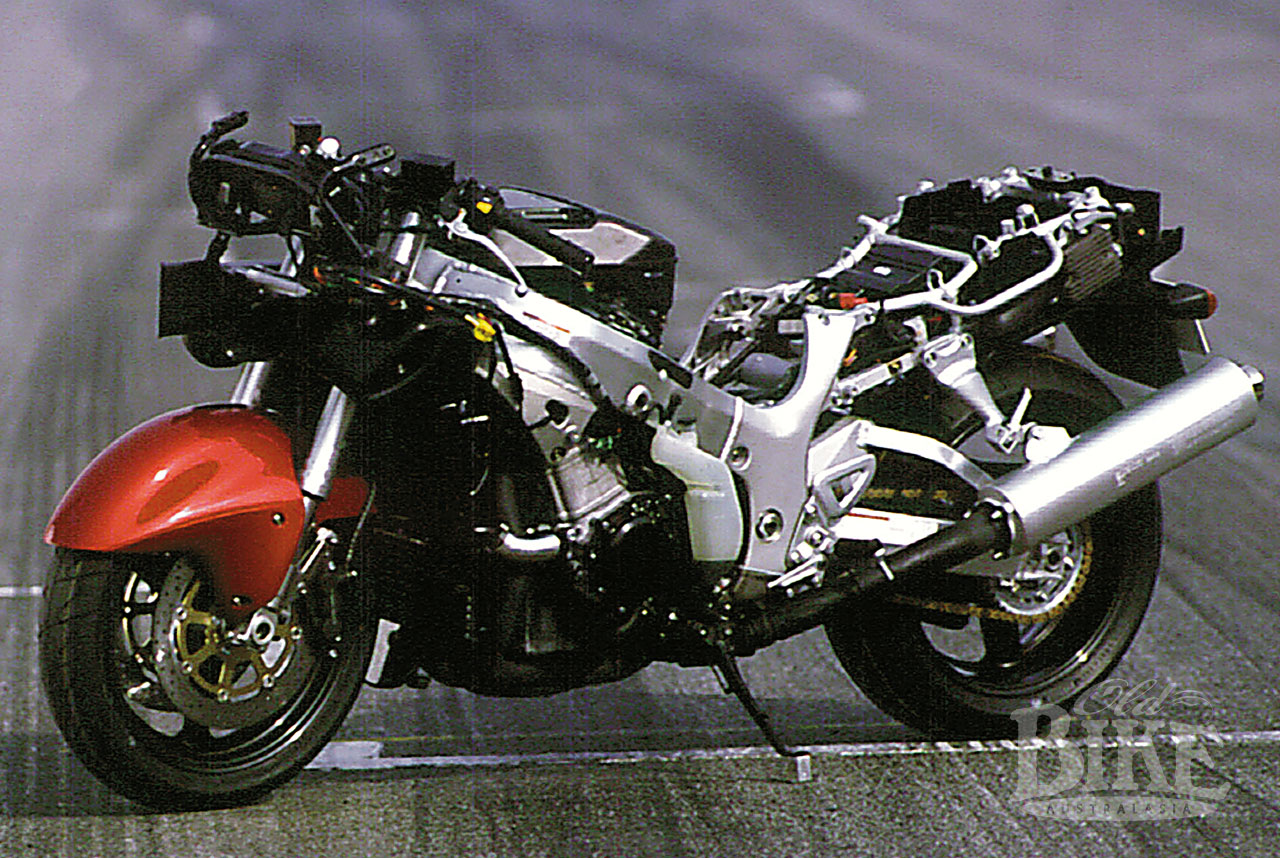

It’s fair to say that the styling of the Haybusa wasn’t everyone’s cup of sake. The front end of the bike indeed resembled the fabled flying version of the Hayabusa, with a droopy snout that was completely enclosed underneath the cowl to prevent ingress of air and lower the CdA (Drag co-efficient). Combined with a similar treatment for the front mudguard that minimised turbulence around the forks and front tyre, the result was a reduction in the tendency for the front wheel to lift at high speed. Even the mirrors were claimed to be of ‘anti lift’ design. The fairing itself extended well forward of the normal pattern, with twin intakes to ram the air into the cavity above the injectors. To permit easy access to the airbox and fuel system, the petrol tank hinged upwards from the rear. The dashboard area abounded in carbon fibre, or at least, material to imitate the look of carbon fibre. Whatever, it looked trick. Apart from the usual twin speedo/tacho, instrumentation consisted of fuel gauge, clock, temperature gauge, LCD odometer and twin tripmeters with fuel consumption gauge.

Naturally, concessions to pillion comfort weren’t high on the list, in fact the pillion accommodation was just a pad (plus a grab rail) that clipped in place of the tail hump behind the rider, under which sat the tool kit. In standard form, there was no side stand, but one was listed as an extra from Suzuki for $230. That accessory list also included a pair of 30 litre Suzuki panniers and a choice of 40 litre or 45 litre top boxes.

Although of seemingly substantial proportion, the rigid twin-spar aluminum frame was actually lighter than the version used on the GSXR750, for minimal weight while maintaining high torsional strength. Up front sat large diameter 43mm inverted front forks with no less than 14 adjustments for compression damping and 13 for rebound, plus 15mm of spring pre-load adjustment giving an almost limitless range of options. For a roadster, the steering geometry was quite sporty – 24.2º rake and 98mm trail. Should the steering prove frisky, a steering damper was standard equipment. Rear suspension was by Suzuki’s proven progressive linkage with a remote reservoir single shock, with 22 adjustments for both compression and rebound damping, and 10mm of spring preload. The 6-piston front calipers came from Tokico, clamping onto twin 320mm floating steel discs, while at the rear sat a single 240mm disc with a 2-piston caliper. Bridgestone BT56 Battlax radial tyres were standard fitment on lightweight 3-spoke 17” aluminum wheels; 3.50” at the front and 6.00” rear.

For such a missile, the Haybusa engine was conventional, albeit, stonkingly powerful. Piston cooling was enhanced by Suzuki’s proven oil-jet cooling, and to cancel, or at least ameliorate the vibes, a gear-driven counter-balancer was fitted, although the feedback to the rider was never one of silky smoothness, possibly because the engine was bolted directly into the frame to aid stiffness. Serious attention paid to reducing component weight wherever possible, including in the valve train with lightweight shim-under bucket adjustment to the valves which were set at a narrow 14º angle. The combustion chambers featured what Suzuki called TSCC (Twin Swirl Combustion Chambers), while to eliminate iron cylinder liners, reduce width, and maximise heat dissipation, the bores were treated with Suzuki Composite Electro-chemical Material (SCEM). Suzuki was known for its fondness for acronyms, and to minimise the expulsion of unburned hydrocarbons in the exhausts had a system they called PAIR (Pulsed-secondary AiR), which used a vacuum-operated system of valves to bleed air into the pipes. The exhaust system was a four-into-two arrangement with stainless steel header pipes connecting to large volume aluminium silencers. The digital direct-ignition system combined an ignition coil with each spark plug cap for reduced weight and stronger spark. The dual headlights were vertically stacked to pit between the air intakes with a 60W projector-type high-beam and a 55W low-beam halogen bulb.

It is a measure of the success of the original design that the Hayabusa has remained largely unaltered, apart for colour schemes, for the entire life of the model. One reason for this was that from 2000, the Japanese and European manufacturers agreed upon a power/speed ceiling, which meant the Haybusa’s claim as king of the heap would never be bettered. For the 2003 model year, a new lightweight 32-bit ECM with 22- trigger pole sensor provided more precise control of ignition timing and injector operation for each cylinder. There was a lighter weight generator rotor, polished stainless steel exhaust pipe, gold anodized brake calipers and black forks.

In 2008, subtle variations were made to the bodywork, including a redesigned tail section that was bulkier and mirrored the front’s ‘droop’ shape, but the biggest changes were to the engine, which was upgraded to meet Euro 3 Emission Standards. This meant fitting a catalytic converter to the exhaust system, which grew in size correspondingly, and enlarging the engine to 1,340cc, boosting power to a staggering 194 hp and torque to 155 Nm. Weight crept up by 5kg to 220kg. The brakes and clutch also received detail mods.

For the 2013 model year, ABS became standard equipment on the Hayabusa, along with radial-mounted Brembo Monobloc front brake calipers. The fuel injection system became a dual throttle valve setup, with what was called S-DMS (Suzuki Drive Mode Selector) providing a choice of three engine maps. A further acronym, SCAS (Suzuki Clutch Assist System) was in other words a slipper clutch to deliver smoother downshifts.

From the moment of its conception, the Hayabusa captured the attention of customisers, modifiers and performance enhancers, not that the performance needed much in the way of enhancing.

As the Hayabusa neared its 20th anniversary, dark clouds were looming. The threat sprang naturally from the ever-stringent European emission controls, and for 2018 Suzuki decided it could no longer justify the expense of meeting these for what was, and had always been, a niche model. However Europe’s lost was Oceania’s gain, and the motorcycle that blew the socks off the pack of journos at Avalon in 1999 continues as part of the 2019 range, as it will in USA, at least for the time being. Suzuki has renewed patents on the Hayabusa tag, indicating that there may be, at some point in the future, a rebirth, but with the price of compliancy being something akin to strangulation, what ever emerges wearing the famous moniker is unlikely to be as ground-shattering as the original.

Phil’s favourite

The Silver Hayabusa, a 2003 model, belonged to Phil Froebel, who clocked up around 30,000 km during his ownership. “At the time I was living on the NSW Central Coast, and I bought the ‘Busa from Central Coast Motorcycles. I was coming off a Yamaha R1, which really was just a racer – you had to wring its neck everywhere you went. The Suzuki was more sensible for what I needed, with its longer wheelbase and better riding position. I’m pretty tall so I put genuine handlebar risers on plus a slightly taller ‘bubble’ screen and it was really comfortable, and it was fast. This colour scheme (silver/grey with red Hayabusa decal on the fairing) was only available for one year (2003) and this was the last model before they changed to the 3-stage engine map. It had Staintune mufflers but otherwise was standard. The ‘Old Highway’ (from Berowra to Gosford) was our race track, and the king of the road was Alan Hales, who had a ‘Busa before he got his Ducati. It was Alan who suggested I got rid of the R1 and got the Suzuki, and it was good advice. I wish I still had it. That bike and my son were the two most valuable things to me that I managed to salvage at my divorce settlement!”

A pigeon pair

The Hayabusa on our cover and on this page belong to Neil Fynney and partner Tracey Bowling. They represent the changing face of the model, being a Generation 1 and 2 respectively. The 1999 ‘Copper’ model (as in colour, not police), and is all original except for the windscreen, which is currently being sourced. It is also a quite significant example, as Neil explains. “It was sold new by McCulloch Suzuki in Perth in April 1999 and has the VIN number 6. I believe six models from the original batch were sent around the country and this one went to WA. I am the third owner and I bought it about 12 months ago with 130,000km on the odometer. The previous owner had set it up with high bars, a big seat, lowered footpegs and Triumph brakes but had kept the original parts in boxes. Mark “Camel” Lange, who is the Hayabusa guru here in WA, rebuilt the original calipers and helped me get it back to original.”

The Copper ‘Busa nicely complimented the 2009 Gen 2 model that Neil has owned for six years. “I was living in Adelaide at the time and I saw this one advertised in Canberra, so I drove over there and brought it back. Then when I went back to Perth it came with me. It had 9,000km on the clock when I bought it and now has 30,000km, and has Yoshimura pipes.” So with two models, ten years apart from which to choose, which one does Neil prefer? “Definitely the ‘09”, he says without hesitation. “I had a 1998 Honda Blackbird, and the Copper feels much the same, like an old bike. I get on the Gen 2 and it’s got more horsepower, better brakes, and it’s smoother. Tracey likes the Copper and we both also ride Harleys, so she’s used to big bikes.”

A ‘Busa day out

The Japanese Bike Show, held on 31st March in Perth (see report OBA 81), celebrated Japanese motorcycles in general, and the Hayabusa in particular. Now fewer than four of the original ‘Copper’ models were on display, plus two later models and a customised version graced the main arena.

The Black sheep

The family resemblance from two decades of Hayabusas runs deep; there is visually very little difference apart from the livery and detail changes. But there is one variation that falls a long way from the family tree – the GSX1300 B-King. Stripped of its distinctive bodywork, the B-King is a Hayabusa sans vêtements, with the same 1340cc engine, and as shown at the 2001 Tokyo Motor Show, supercharged to produce around 240 bhp. The B King remained a fanciful concept bike until Suzuki sprang a surprise by putting it into production for the 2008 model year. The new model had changed considerably from the concept bike, notably with the removal of the supercharger, and a power output 10 bhp down on the standard Hayabusa. The exhaust pipes with their massive silencers exit under the seat and the whole package weighs 235kg dry.

The B-King shown here, a 2008 model, belongs to Mark Hollingshed, who is also a keen classic sidecar racer. He explains some of the features. “The new (Gen 2) engine appeared in the B King before the Hayabusa. The model ran from 2007 (in black or black/silver) until 2010 when it was in Suzuki blue and white. It has a complex four-into-two-into-one-into-two exhaust system, with the single pipe sitting beside the shock absorber before it splits into two mufflers under the seat. This one has Yoshimura carbon mufflers which fit in under the standard shrouds. There are lots of visual differences to the standard Hayabusa which are obvious, but it also has Nissin brakes instead of Tokico. I go on a couple of longish rides per year and I find it really comfortable. It has plenty of poke but it is so flexible you can ride it in top gear almost anywhere.”

Specifications: Suzuki GSX1300R (1999)

Engine: Four cylinder, liquid cooled 16 valve DOHC, 4 valves per cylinder.

Bore x stroke: 81mm x 63mm

Capacity: 1298cc

Compression ratio: 11.0:1

Ignition: Digital Electronic

Fuel system: EFI with 4 x 46mm throttle bodies with single injectors.

Lubrication: Wet sump

Gearbox: Six-speed.

Frame: Aluminium twin spar

Wheelbase: 1485mm

Suspension: Front: 43mm inverted telescopic forks with inner cartridge, 14-step rebound and 13-step compression damping, 120mm travel.

Rear: Swinging arm with progressive linkage, 22 step compression and rebound damping, 140mm travel.

Wheels: Front: Three-spoke cast alloy 3.50 x 17; Rear: 6.00 x 17

Tyres: Front: 120/70ZR – 17; Rear: 190/50ZR – 17

Brakes: Front: 2 x 320mm floating steel discs with Tokico 6-piston calipers

Rear: 1 x 240mm steel disc with 2-piston caliper.

Dry weight: 215kg

Seat height: 805mm

Fuel capacity: 22 litres

Power: 175ps (172.5hp) at 9,800 rpm

Torque: 138.3 Nm at 7,000 rpm.

Top speed: 310 km/h

Price: (1999 Australia) $17,490 + ORC