From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 70 – first published in 2017.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: John Ford, Ross Hannan and Jim Scaysbrook.

It is a testimony to the brilliance of the original Honda CB750 that it lasted, basically unchanged, for as long as it did. From 1968 to 1976, the CB750, from the 1969 original to the K6, sold in massive numbers, performed almost faultlessly, and introduced uncountable numbers of people to what was then large-capacity motorcycling.

But like all brilliant ideas, the CB750 was in the cross-hairs of its rivals from day one, not just with across-the-frame fours like the Z1 Kawasaki and the later GS750 Suzuki, but other big bores that even included the Suzuki GT750 and briefly, the Yamaha TX750. Even though the Z1 established a sub-class of 900cc, there was still something traditional about 750cc motorcycles that the Honda graciously championed. The new Suzuki GS750, with its double overhead camshaft engine and superlative handling, was audaciously poised to snaffle Honda’s previously unchallenged position in the 750cc category, so by the mid-seventies the Big H seriously needed another arrow in its quiver, and it came in the form of the CB750F, which very soon became the CB750F1 and eventually the CB750F2.

The new F was released initially as a USA-only model, but it failed to excite for various reasons, one being the increased weight, from the K2’s 226kg to 244kg (wet). Another factor to the American indifference was undoubtedly the styling, which lay somewhere between a sporting model and a tourer, but satisfied neither completely. In Britain, the F1 was universally referred to as a Café racer, which is stretching the point a bit. The original F lasted only briefly in its solo status in USA before it was replaced by the virtually identical F1, not just in USA but in other markets around the world. In fact the Yankee coolness to the F1 resulted in a stay of execution for the K series, which plodded on in K7 and K8 form before finally bowing out in 1978 when the all-new twin cam models came on stream.

The new F sold alongside the four-pipe K6, which differed only marginally since the introduction of the K1 but had progressively become slower. In Australia, the K2, which was introduced in 1972 had a very long innings, as we did not receive the K3, K4 or K5 models. Styling wise, the F was a complete departure from the K models, but retained as its heart the proven, virtually bullet-proof, single overhead camshaft two-valve four. There were some changes inside the engine however; the cylinder head was internally new, with a higher-spec camshaft, and slightly higher compression 9.2:1 pistons were in the block. Fourth and fifth gears were altered for a closer set of ratios, and the primary drive ratio was higher by 3%. The increased performance was an important selling point, because the K series had gradually lost some of the punch of the earlier models in a quest for quietness of operation and smoother power delivery. Not that the revised specs for the F produced neck-snapping acceleration, but with a revitalised appetite for revs (now red-lined at 8,500), Honda thought it advisable to uprate the clutch basket and plates at the same time.

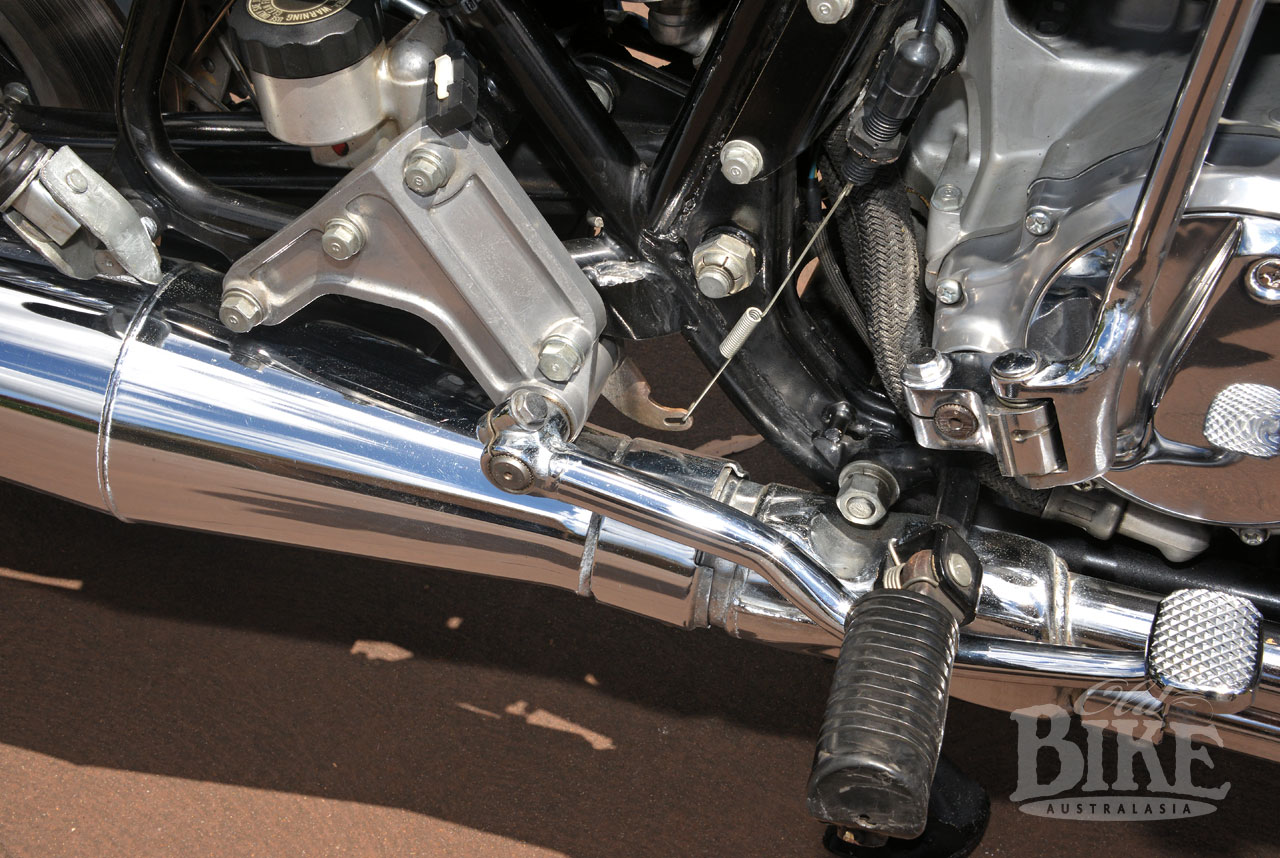

Replacing the much-admired four separate exhaust pipes and mufflers was a four-into-one system with a fairly bulbous and unfortunately low-slung muffler on the right side. The loss of the mufflers on the left side meant the chain run and rear sprocket was now exposed – a raw appearance that did not sit well with some buyers. With dealers reporting fairly robust resistance to this and other aspects of the F’s styling, the K series was resurrected in the form of the K7 and finally, the K8.

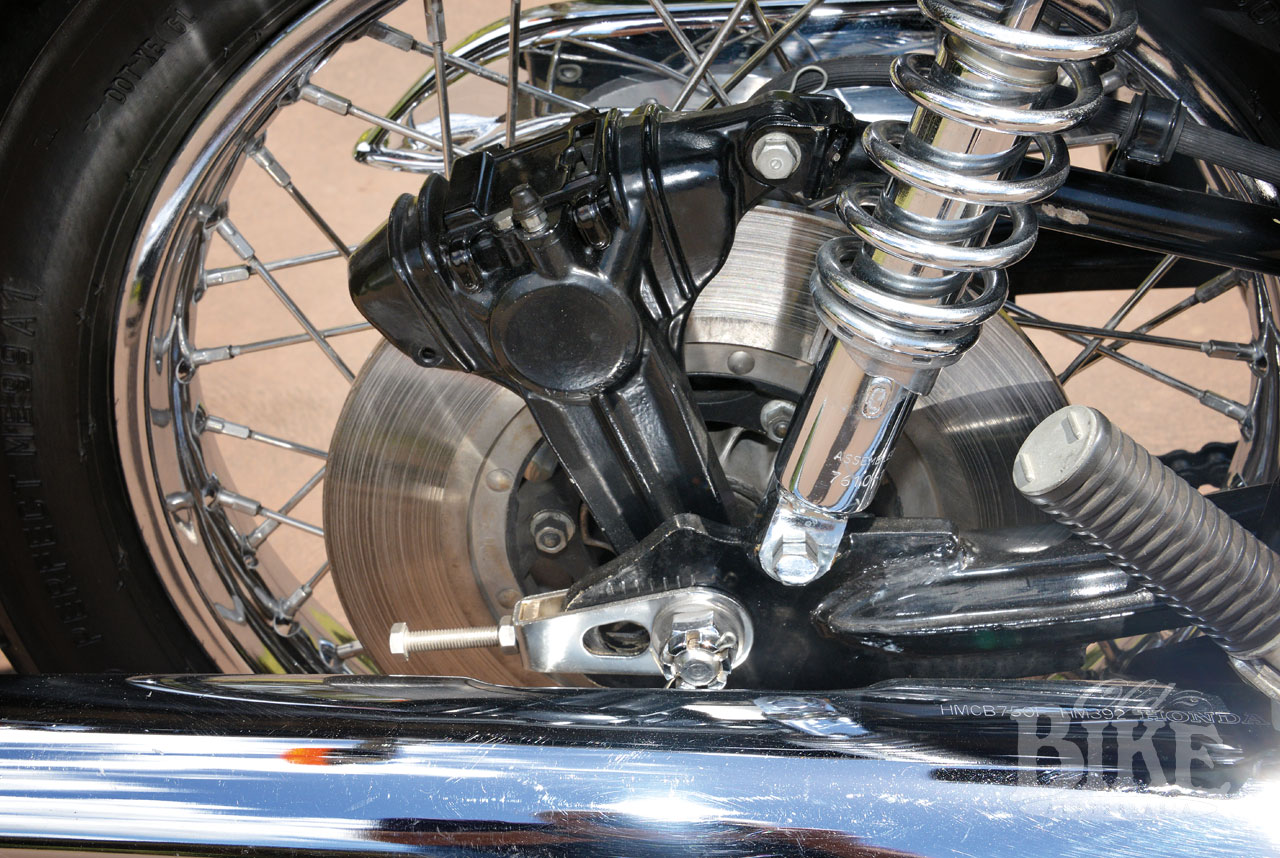

While the F’s frame appeared identical to the K, it too bore subtle differences, most visibly for the mounting loops for the muffler bracket and rear brake mounting plate, and with a longer and more robust swinging arm giving an increased wheelbase. The steering geometry was slightly revised, with a steering head angle of 28 degrees and triple clamps sporting less offset – all designed to reduce the laziness of the steering. The K’s long-running rear drum brake was gone, replaced by a big 300mm disc that employed a dual opposed-piston caliper that was considerably more powerful than the front. Oddly, the front stopper retained a slightly revised single piston set-up. A very curious engineering decision, to be sure. The F and F1 retained traditional steel rims and spokes, 19 inch at the front and 18 rear. A 530 rear chain was standard.

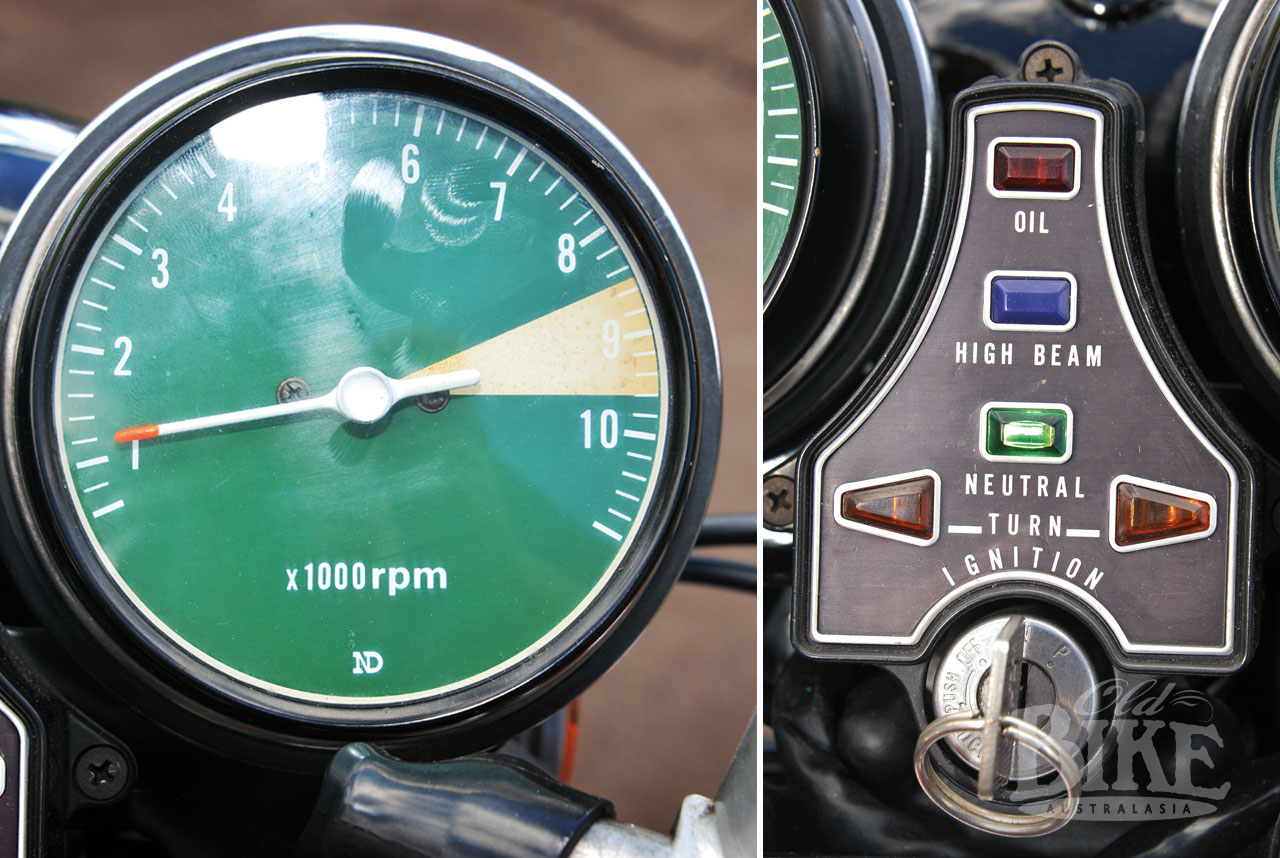

Up front, ‘naked’ front forks dispensed with the K’s signature headlamp brackets and rubber gaiters in favour of the exposed stanchions pioneered by the likes of Ceriani. The rear shocks, made by Showa, were virtually identical to the K6, but without the chrome upper shrouds. The headlight itself, which came from the parts bin of the twin-cylinder CB500T, was mounted on a tubular bracket that owed its inspiration to that on the CB400/4. Finally, one of the most criticised features of the K-series – the positioning of the ignition switch under the left side of the petrol tank – was addressed, and the switch migrated to a comfortable and easily accessible location between the speedo and tacho. It now sat in a cluster that included the usual warning lights for oil pressure, high beam, neutral and turn indicators.

In keeping with the sporty styling, footrests were moved rearwards and mounted on cast aluminium brackets. On the right side, this bracket also served as the pivot mount for the rear brake pedal, which on the Ks had pivoted on a tubed welded to the frame. The kick starter’s main boss was cranked out to clear the footrests. New, matt-black painted plastic side covers now occupied the midriff section, with a redesigned oil tank hidden away, without the previous exposed filler cap and dipstick. This meant the right side cover had to be removed to check the oil level. The seat now finished in a tail piece colour-matched to the fuel tank, and in this rearward section (which also incorporated the plastic rear mudguard) was a small compartment for holding things like the owner’s manual. The tool kit now sat on a shelf beside the battery.

In the USA, just over 15,000 examples of the CB750F found buyers in 1975, and in the following year, when the F1 was released to worldwide markets (once existing stocks of the K series had departed dealers’ showrooms), a total of 48,295 were sold. The F1, available in Sulfur Yellow or Candy Antares Red, was almost identical to the F, save for the introduction of thinner piston rings which were introduced during the F production. The twin Nippon Denso instruments, which harked back to the original CB750, changed from dark blue on the F to light green faces on the F1.

Compared to the heady days of the big selling K1 and K2, sales of the F1 were still modest in the face of serious competition, so Honda’s retaliation was the F2, which differed quite a bit from the F1. The CB750F2 (and the US-only F3) embarked on further styling tricks with an all-black engine, a less angular four-into-one exhaust system with a megaphone style muffler that was slightly upswept for increased ground clearance, and Honda’s curious Comstar wheels – cast alloy rims held in place by riveted-on five-spoke steel pressings that were noted for their ability to be buckled in the simple process of changing a tyre. At last, the under-performing single disc and single piston caliper was gone from the front end, replaced by a pair of 275mm Nissin discs, mounted to the rear of the fork legs. These were still single-piston type, but bolted to a bracket and directly to the fork leg (instead of via the earlier pivoted-arm bracket). In a retro styling move, conventional headlight brackets reappeared.

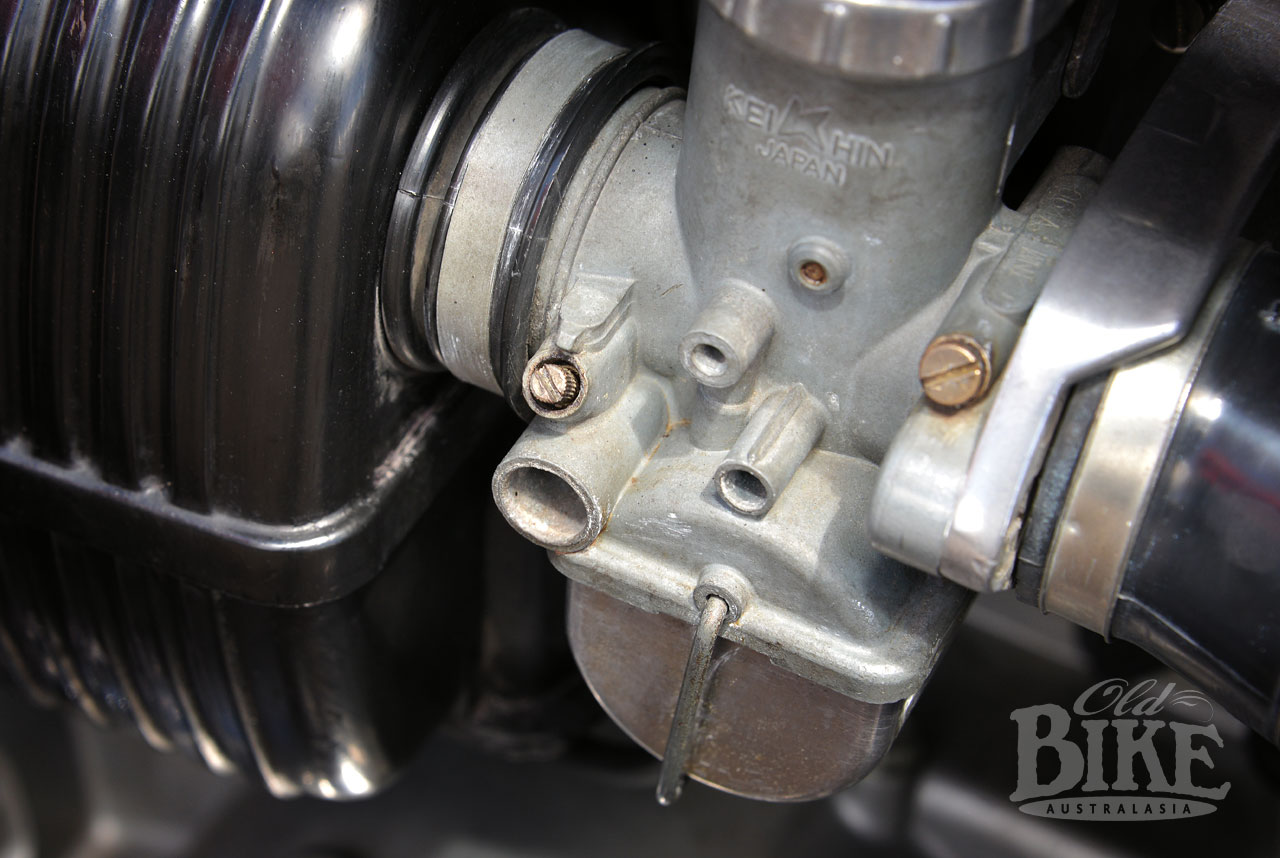

The F2 saw a slight decrease in compression ratio but with a redesigned cylinder head sporting larger inlet ports, with both inlet and exhaust valves increased in diameter with revised angles in the head. There were also stronger conrods and new Keihin carburettors with accelerator pumps. The camshaft introduced for the F was further up-rated and along with the other changes, pushed power up to 73hp at 9,300 rpm. The original 1969 CB750 was listed by Honda as producing 67PS (66.1hp) at 8,000 rpm. The new specification was sufficient to warrant a slight beefing up of the crankshaft, cylinder head studs and clutch springs. Naturally the tachometer (now black-faced) was red-lined at 9,500rpm.

The last hurrah for the F series was the F3 of 1978 (it was already common knowledge that the new twin-cam design was imminent) and was again a USA-only model, differing only in minute detail from the F2.

One for the road

Clyde Ikin is a CB750 fan; he owns four in total, from a 1971 K1, a K2, CR750 replica, and the featured CB750 F1. He’s also extremely knowledgeable about the intricacies of each model, what works and what to watch out for. In his view, the F1 is the pick of the crop, for a number of reasons. “Out of all my bikes, including the Z1 (featured in OBA 31), Suzuki Water Bottle, my K2 or the F1, I would pick the F1 for long rides. It’s been (from Sydney) to Phillip Island twice, and the last time I put an extra tooth on the countershaft sprocket for a bit higher speed and it pulls it fine with no real difference in acceleration. Fourth and fifth gears are slightly higher than the K2 – top gear is 0.97:1 instead of 0.94 I guess that’s because the engine revs higher.

“Considering that the original CB750 was probably the quickest and was red lined at 8,500, whereas this dropped back to 8,000 on the K2, the F1 is red lined at 8,500 and would be just as powerful as the first model due to slightly higher compression ratio and a hotter camshaft. Honda was trying to recover the power that had been lost in the K1-K6 series because of restrictive air boxes, mufflers and so on. The F1 is no lighter than the K2; the rear disc is heavy – the same size as the front and actually similar to the Gold Wing. The front forks are slightly different with the aluminium sliders about 20mm longer for extra rigidity, and the front brake is marginally better. It has a 42mm diameter caliper piston instead of 38mm so it has more hydraulic leverage, and this brake continued on the K7 and K8 US models. The offset has been reduced on the F1 with a slightly different head angle and I think it turns better. The pillion seat is really comfortable too for my wife Vicki, she says it’s even more comfortable than the Suzuki. The F1 had some nice improvements like moving the ignition switch up to the centre of the console, but a lot of people didn’t like the styling and the four-into one exhaust with the big cigar shaped muffler. It makes the left side of the bike look a bit strange without the pipes there. The general opinion seems to be that the F1 (and F2) were not good sellers, but in 1976 the F1 matched the Z900 for sales in USA at over 22,000 units, so it can’t have been that bad. Globally, it marginally outsold the K6. I still like it. This bike was my daily ride for quite a while and has been continually registered since it was rebuilt in 1997. I just need to find the time to ride it more.”

Once more around Amaroo

By 1975 the days of the Honda CB750 as a weapon in Production Racing were well and truly over. It left sporting minded Honda dealers with little to do but watch when it came time for Australia’s premier event, the Castrol Six Hour Race, to roll around. Yet, come October, two new CB750F1s were amongst the entries in the Unlimited class, which was an eclectic mixture of Kawasakis (Z1 900s and H2 75os), Laverda 750s, Ducati 900SS, BMW R90S, a Triumph 750, a Norton 850 and a few Yamaha 350s. The two Honda entries came from Ross Hannan Yoshimura (the bike actually owned by Bennett Honda) to be ridden by Tony Hatton and Garry Thomas, and a dealer entry from Bondi Motorcycle Supermarket for Greg McDonald and Ian Scattergood. Ross Hannan recalls, “The whole thing about entering the F1 was (NSW Sales Manager) George Pyne’s idea, to publicise the model, so I said OK, let’s do it. It was hard because it was so bloody slow, and nothing we could do would speed things up.”

With Amaroo’s clockwise direction, another major drawback was the right-side muffler, which dragged on the deck at the slightest provocation. An hour and a half into the race, the rain that had threatened all morning turned real, and the resulting dump saw McDonald drop his F1 at the slow Rothmans Corner. He was quickly up and on the go again, but the big mover was the Hatton/Thomas F1, with Garry aboard, which climbed from 18th to 5th while the track was wet. As the track dried, normal service was resumed, but at the end of the race, Hatton and Thomas had clocked up 326 laps (9 behind the winning Z1 of Gregg Hansford and Murray Sayle) to claim a creditable 6th place, while McDonald and Scattergood notched up 309 laps for 22nd position.

Two years later, Highway Motorcycles at Gordon on Sydney’s north shore entered a CB750F2 for Mick O’Brien and Stephen Hardwick, the pair bringing the Honda home in 18th place on 335 laps, 21 behind the winning BMW of Ken Blake/Joe Eastmure.