From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 70 – first published in 2018.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Rob Lewis, Yamaha, Ducati, John Ford, Burgess archives.

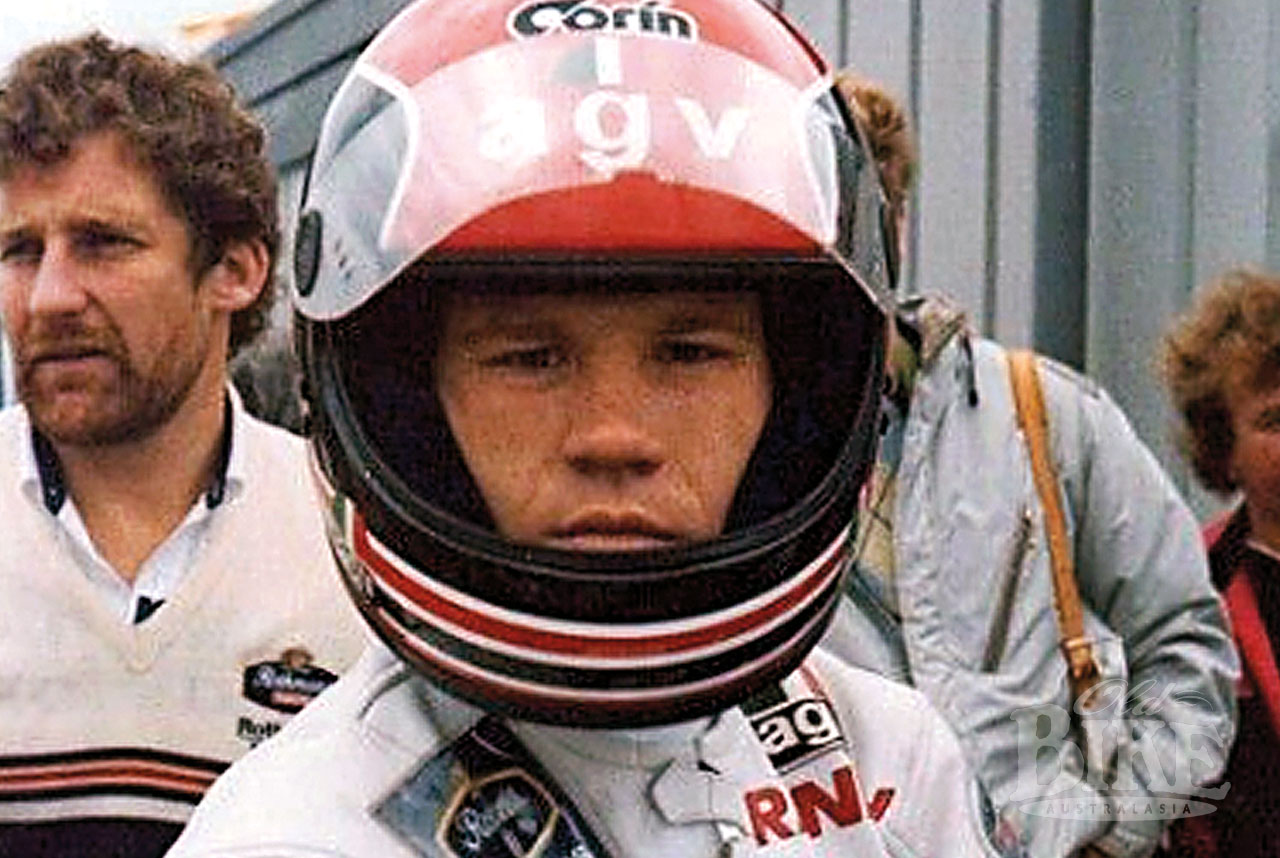

After a short but enjoyable career as a rider, Jeremy Burgess became, almost by accident, the man charged with guiding the careers of some of the world’s most legendary riders. With 13 World Championships in 500cc and Moto GP to his credit, ‘JB’ has a record unique in the sport.

In his self-built home in the Adelaide Hills, 64-year old Jeremy Burgess appears not to have a care in the world, nor an enemy. In the garage is his restored Jaguar, a long-term project now nearing completion, with a Triumph T3A next in line. There’s a day of golf each week, a few speaking engagements, and appearances at events like the Levels Classic in Timaru and the International Festival of Speed at SMSP. Indeed, life these days is pretty relaxed – a direct contrast to the previous 35 years on the Grand Prix trail that included high-profile (and high pressure) stints as crew chief to Wayne Gardner, Mick Doohan, and, from 1999, Valentino Rossi. It’s true that that career came to a sudden end, but it wasn’t unexpected, says Jeremy with a typical shrug.

What is all the more remarkable is that Jeremy managed to achieve all this with no formal training. “I have no qualifications whatsoever,” he says offhandedly. We (our family) were all given the opportunity of a university education. My brother studied law. One sister is a doctor and the other sister works in publishing in Melbourne. But I bailed out of school about a week before the final exams in 5th year, stupidly, and worked in a tile factory that was paying adult wages – $54 a week on day shift and $57 a week on afternoon shift. For a young bloke, it was the same money a guy was getting who was raising a family and paying a mortgage. So through my working life there and later in a brick company I’d just get all the overtime I could get. We had a newspaper here called The News, and everybody bought a copy at lunch time and if you had your photograph in The News from the bike racing on the weekend you were almost a hero. So they gave me a lot of time off on the condition that I would work the weekends when I was home. So I was driving fork lifts and loading and unloading kilns. I did a stint drilling bore water and minerals for a while in the South East. It was all a means to make money and go motor bike racing, but in hindsight I should have taken the university option – I would have done engineering, probably civil engineering.”

For Jeremy, racing a motorcycle began towards the end of 1972, and it was a painful baptism. “I needed a motorcycle to go to work, cheap transport, and you meet like-minded people, and I remember one of them saying, ‘Why don’t you come out to the race track on a Saturday afternoon – AIR had just opened – and just have a ride around?’ So I went out there, whizzed around on my H2 750 Kawasaki and thought, ‘This is pretty good’. Out of every bad comes a bit of good. At my first meeting I crashed in practice and ended up taking the back out of my hand and spending a week in Adelaide hospital with a skin graft. I never made it into the race. But undeterred I came back in March of the following year when they had the Advertiser Three Hour, and finished third riding with Geoff Ellis on my H2 – the first South Australian team home. Out of that you get gifts. One was a free entry to the 1973 Castrol Six Hour in Sydney. That was probably the last thing we wanted with the sort of experience we had, but I kept racing in South Australia at Mount Gambier and we went over to Calder for their Two Hour and then to the Six Hour, all on the H2. At the Six Hour we only did practice, my mate went picking daisies at Cattai Creek and crashed the bike.

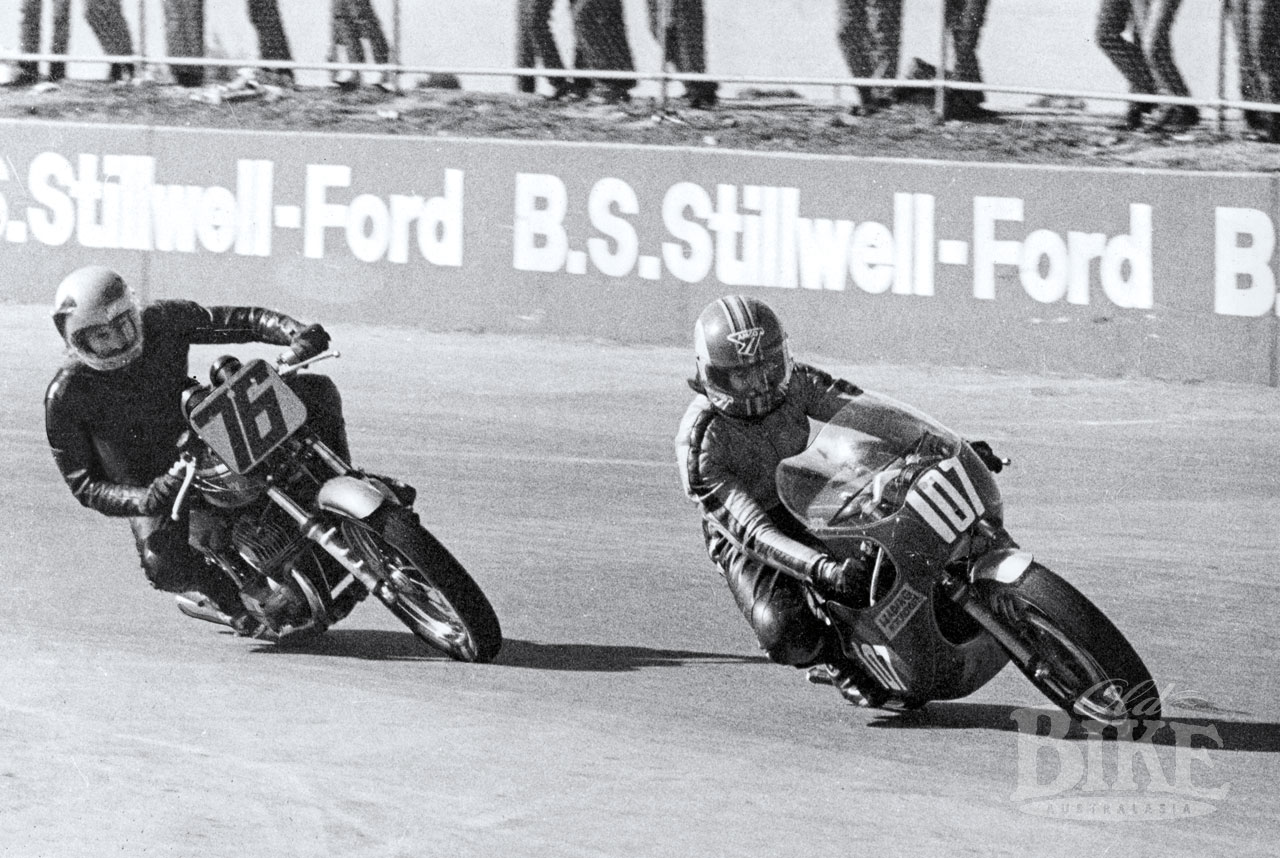

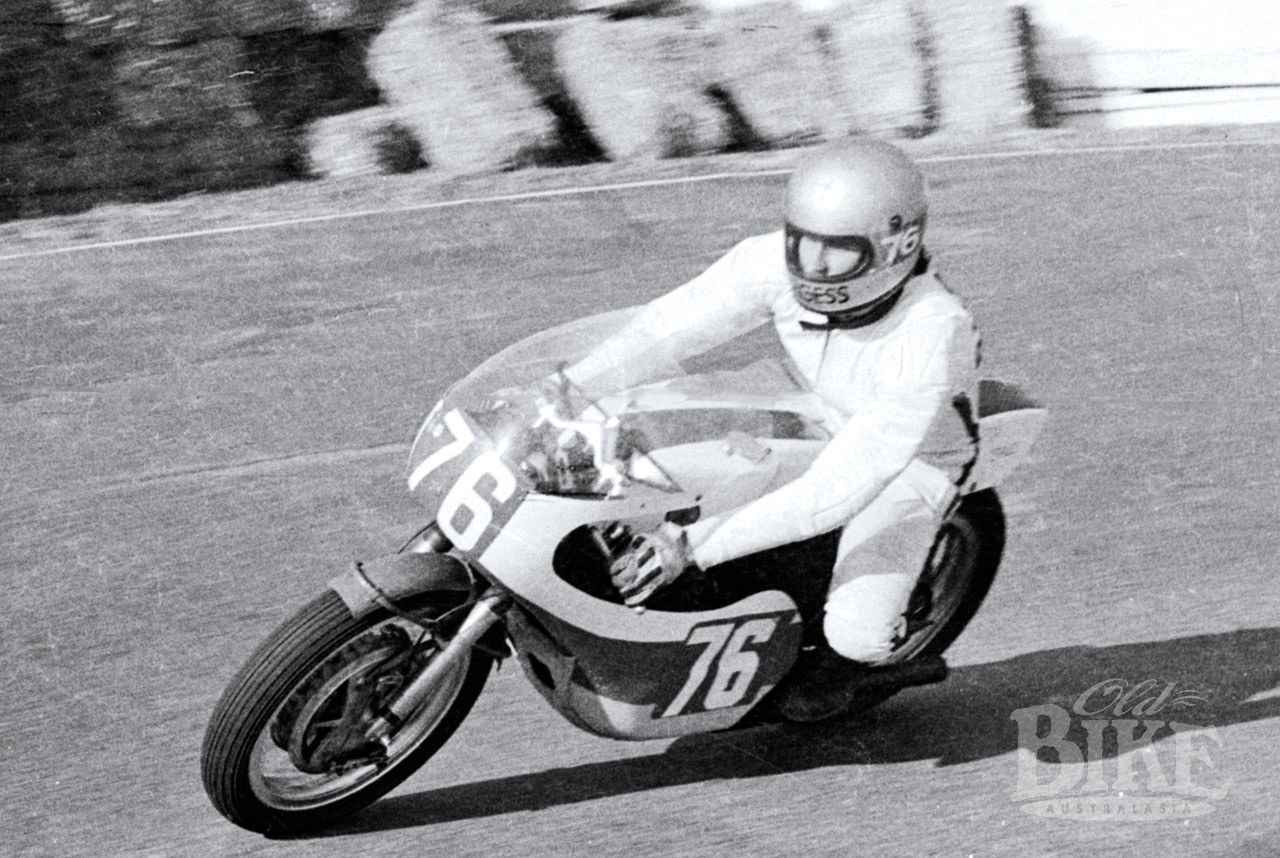

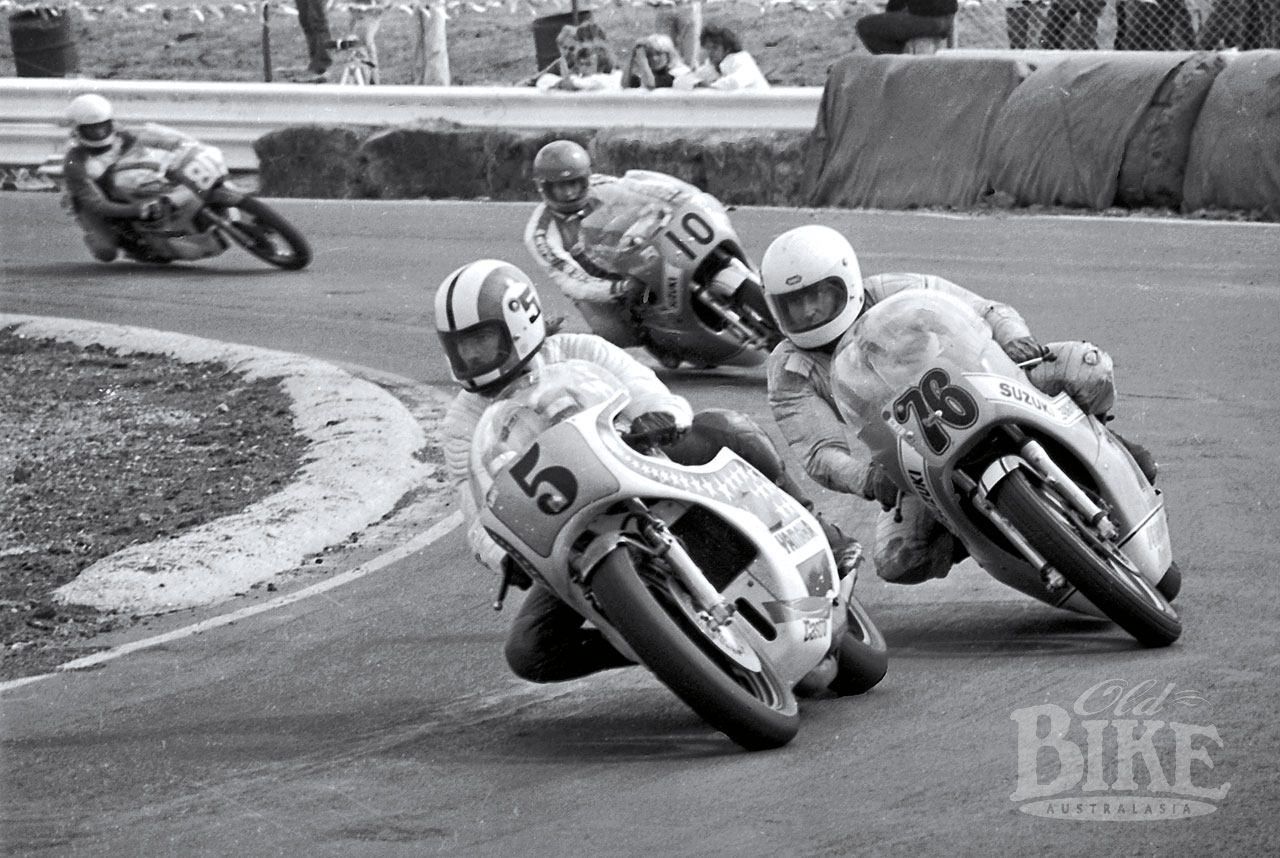

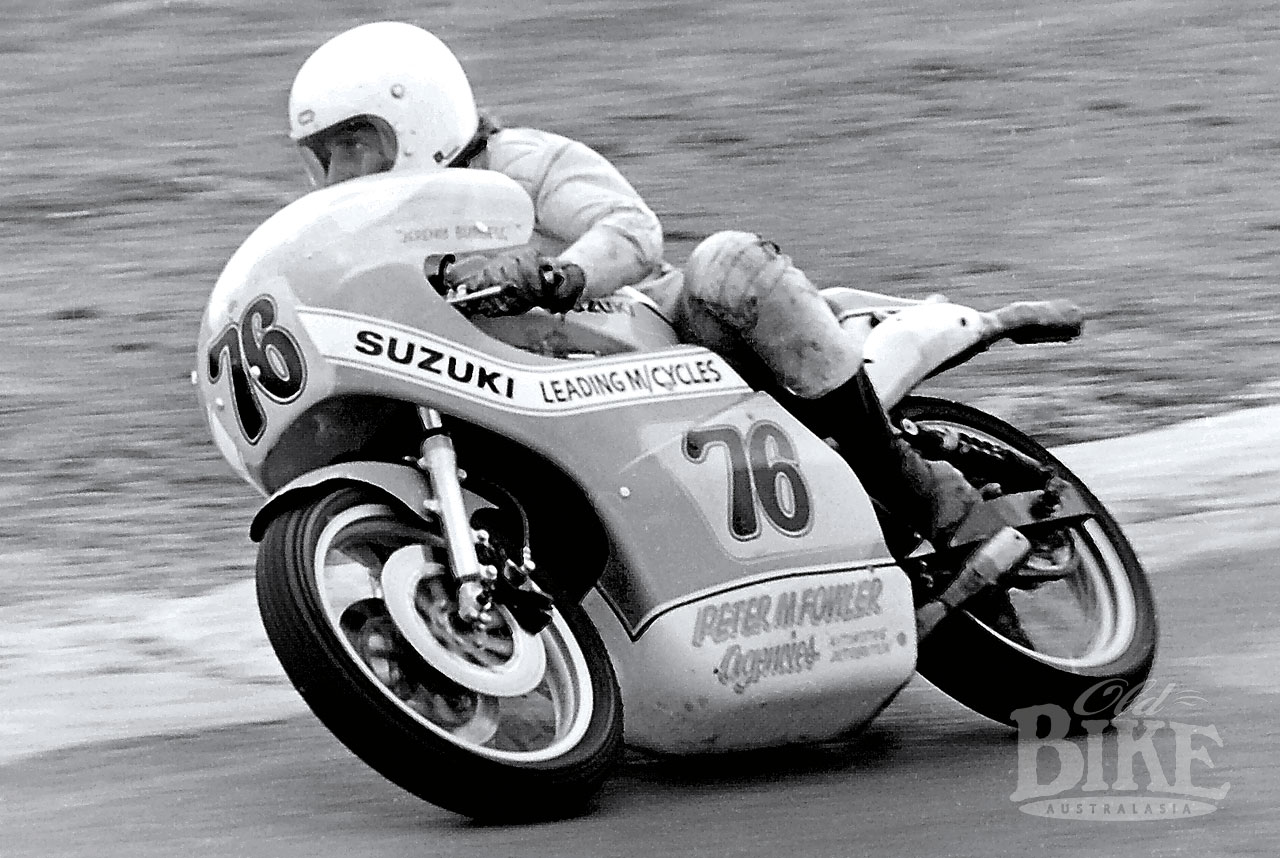

“That year I bought a TZ350 Yamaha, and that did me until 1976 when I got my RG500, which I enjoyed immensely. In fact, I enjoyed it all but I look back on it and think, ‘Gee if there had been some mentoring it could have gone a lot further and I never realised the importance of having somebody give you a bit of advice. Carl Hammersley and I had a little business together doing fibreglass work through the week. We’d make some moulds for fairings and seats and knock a few out to take to race meetings and if we made 50 or 100 dollars it all helped. I ran the Suzuki for half of ‘76, and ‘77, ‘78. We did a meeting at Calder and it just all clicked on that day. I beat Murray Sayle, Jeff Sayle and Bob Rosenthal. Mick Hone pipped me for the 500 Victorian title, we swapped the lead throughout the race on our RGs and I made the mistake every rider makes once in his life, I went too cautious on the last corner and Mick got me to the line.

“I bought the ex-Pitmans Des Larner TZ700 which was an early model that they had changed into a cantilever. There was a guy called O’Neill who raced sidecars in Queensland, and he bought a brand new TZ750D and took the engine out. So he shipped the brand new bike down to me, with the exhaust pipes and everything. I took the engine out of the Pitmans bike and sold the remaining monoshock chassis to some guy on the street who put an engine in it. When I went to Europe I sold it to Kym Coleby who won the B Grade at Bathurst on it in 1980 but later had a big crash at Turn One at Oran Park. Carl had been killed in ’78, and I lost the driving force for racing.”

In 1980, Jeremy was at the crossroads, unsure of whether to continue racing or embark on a different career path. Then, out of the blue, came a life-changing moment. Greg Pretty was going to Europe, so I said, ‘Oh well, I might as well go with you, what flight are you on?’ It didn’t work for Greg unfortunately. He really needed his mother’s cooking – he couldn’t really look after himself, so he found it extremely hard in the UK. Stu Avant picked us up at the airport and whizzed us round to Mick Smith’s place in Surbiton. I ended up staying with Mick for a long time. I gave Greg a bit of assistance in getting a van in London, but in no way was I tied to Greg. When Mick said they were looking for a mechanic at Suzuki GB, I said, ‘Well, put my name down with the other five hundred you’ve got!’ but they called me in on a Saturday morning and Rex White (the boss) was there. In a way I was dead lucky because I knew (American mechanic) George Vukmanovich who was working there for Randy Mamola. I’d met Randy in ’76 in New Zealand when he was there, and I knew Graeme Crosby who was the other rider, and I was staying with Mick Smith, so it all fell together. Also the fact that I’d run an RG in Australia helped.”

This was baptism by fire – a job on the spanners with one of the highest profile teams in Grand Prix racing. “When I started with Suzuki GB it was straight into the GPs. It was one of those situations where you were really learning on the job. I had no experience at that level and didn’t know what to expect, but when you understand how the factory teams work, they don’t sign riders just to run middle of the pack, so there was a lot of pressure on the staff and everybody to do well. Randy was expected to win but unfortunately the Italians Lucchinelli and Uncini being on the Michelin tyres was definitely an advantage – we were on Dunlops – and getting 90 thousand quid into the team a year from Dunlop helped Suzuki GB but it didn’t do anything for Randy. George and I worked on Randy’s bike for ‘80, ‘81 and ‘82. Not only did we contest the GPs of which there were only about 8 or 9, we did the British Championship races, and that was a very strong series then. The ITV series, the Shellsport 500 Championships was massive, and just to see the British riders who were making a living solely from racing in the UK – people like John Newbold, Mick Grant, Barry Ditchburn, dozens of them who had great backing from a motorcycle dealer, they had their Mercedes van, a caravan, a mechanic, and there was a race on every weekend somewhere in the UK. It was a brilliant time. Plus there were all the other internationals, like the street circuits in Holland. I came home at the end of 1980 and Randy gave me 1000 dollars which I bought my ticket with to go back the following February.

“Suzuki GB pulled back at the end of ‘82. Dennis Rohan was the boss of Suzuki at the time I got a letter saying services wouldn’t be required for ‘83. So that was OK, I had a bit of work here (in Adelaide), foundation work, so I learned how to finish concrete, to fill in a bit of time. Then blow me down but two GPs into the season Honda ring me and want me to go and work with Ron Haslam in Belgium. HIRCO which was the old Honda International Racing had moved from England to Belgium and they were running Marco Lucchinelli, Freddie Spencer, Takazumi Katayama and Ron Haslam, all on the triple cylinder NS500. I ended up working under Dozy Ballington who is Kork Ballington’s brother. We got on famously, I’d known him from his Kawasaki days in 80-82, so away we went and I stayed there 21 years at Aalst, between Brussels and Ostend.

“I worked with Ron in ‘83-‘85. Then Irv Kanemoto asked me to come across and help Freddie Spencer, working on the 500 when he was going to have a crack at the double 250/500 championship. Stuart Shenton and a French chap named Gilles were looking after the 250. The 250 guys helped us a lot so without Stuart and Gilles the task would have been far more difficult. I had to learn a bit of my trade, to sort of work out what Freddie would have been saying, because Irv would have so much on his plate. And then at the end of ‘85 we had that massive input from Rothmans as a sponsor and they wanted to go with a two rider team and that’s where Wayne Gardner got his start. Irv rang me and said Honda would like me to look after Wayne. And I said, “Oh mate, I’m happy enough working with you. I like working with Freddie, we get through the work all right,” and he said, “Yeah I know, but I think it would be good for you.” Then Mr Aguma who was the president of Honda Racing gets on the phone a couple of days later and tells me in no uncertain terms, “If we believe you can do the job, and you don’t take the job, you’re of no future value to Honda.”

“I didn’t know Wayne in any personal level at all, so I was now the Crew Chief, telling everyone what to do. I’d always been told to do something, and I’d go and do it. However, the decision was made and away we went for ‘86. Looking back, it was a very good move because Freddie hurt himself, his contact lenses were falling out, the Japanese realised the bike wasn’t any good, we saw more photos of Wayne with his feet off the pegs than on the pegs, so they sat down and by ‘87 they’d built a beauty and he won the championship. I give a lot of credit to Wayne for what we have today at Phillip Island and Eastern Creek.”

“You never let the rider get involved with the development of the bike. With Wayne, they asked him what he wanted for ’88 and he asked for a thousand more rpm on the top, and a softer ride, and they lowered the swing arm pivot 20 mm and made a horrible engine and it was a disaster. Two or three GPs into the season Wayne’s got blisters all over his hands. It took us four races, because the swing arm pivot wasn’t adjustable, to raise everything up, then cut the frame and push the steering head out, otherwise we were just going to keep tipping it on its nose. But we did come back and he won a few races in the middle of the year.”

“At the end of ‘88, Mr Aguma says to me again, “We’d like you to go to Winton to talk to a young kid called Michael Doohan and make sure he signs with us.” So I jumped in the car and drove over there from Adelaide. I went to the track and one of the first faces I see is Warren (Willing) who told me that Mick had signed for Honda. Mick seemed like a pretty nice young chap, never got out of his leathers, talked to everybody, so that was the start of the Doohan era. Aguma said, ‘We want you to do with Mick Doohan what you did with Wayne Gardner’. Of course ‘89 wasn’t a good year for Wayne, and he got the news that Eddie Lawson was signed for Honda in an operation set up by Irv, and that really chewed Wayne. And I can understand why, he’d come second the previous year on clearly a bike that wasn’t good enough. To be fair with Wayne, he did say to me in ‘90, ‘I won’t win many more but that kid (Mick) will win plenty’. Then in ‘92 they told Wayne that he wouldn’t be getting factory bikes for ‘93, so he went out and won the British GP at Donington, just to prove a point.”

“Initially, Mick thought he was faster than he really was. It wasn’t an easy bike in ‘89. Irv and Eddie had 13 chassis in it, we were the last on the pecking order of course and this was getting up Mick’s nose. He finished ninth in the championship and a year later he finished third in the championship, so he had to pick his markers based on experience and he was able to do that. He was very good to work with. He had a short fuse, but nine times out of ten he didn’t pick on me. He was a very determined young man and a pleasure to work with. GP wise, we were always expected to win the world championship. We had a very lean period between Eddie going back to Yamaha and Mick winning the first one in ‘94, so there was an enormous amount of pressure from Japan then. I was a mess that year. I had all these blisters from shingles and I thought, ‘God I’ve got to stop sitting in these plastic chairs.’ I’d ring my sister who is a doctor and I’d say, ‘Kate, I’ve got all this rash’, and she’d say, ‘Is it horizontal around your chest? Well it’s going to get worse before it gets better. In ‘92 Mick had broken his leg and in ‘93 it had a big curve in it but he wouldn’t stop trying. To see him lying in that hospital in Bologna, with the bone exposed from where the necrosis had just eaten back, and then they stitched both his legs together to give more blood to the bottom of his foot. Then he turned up in Brazil and passed the medical and was sixth fastest in the wet, but lost the championship by four points. But you know as pragmatic as Mick is he said, ‘You know JB, out of that I might have quit after that season if I’d won the championship. The fact that I didn’t and came back in ‘93, and had won races before the injury I knew what I needed to do to win more races.’

“He couldn’t use his foot, and the rear brake for him was pretty essential so we tried a system with another lever above the clutch lever for him, but that didn’t work where he had to use the clutch and the brake. At Eastern Creek we came up with another one activated by the clutch under the engine, so when he pulled the clutch fully in, the rear brake would come on. That wasn’t very good for other reasons and then one day he said, ‘JB, I ride a jet ski and I’m not doing anything with my left thumb. Can you design me something I can push with my thumb? So we thought about it and Alex Briggs in Canberra went and saw one of his mates and they machined up a couple of bits and pieces and we got it on the bike, Brembo became involved, Honda got enthusiastic. So it worked and suddenly, Mick’s winning races and championships and thumb-operated brakes are on everybody’s bike. But Mick said to me, ‘If I had a good leg I wouldn’t be using that.’ It came and went, you don’t see it in Moto GP any more.”

With five consecutive World 500 titles, it looked like the Doohan/Burgess juggernaut would go on forever. Then came Jerez in 1999, the third race of the season. “When Mick smashed himself up in Jerez, we sort of thought he was coming back but by mid-season he made the announcement that he was retiring. I’d been home most of that year, 1999, so Mick at that time was putting together a team with big sponsorship from Shell International, so Honda let me go and said ‘You’ll be working in Mick’s team and they would share the sponsorship’, so a few of us were given the drum, I went and recruited a couple of other people. Valentino Rossi was going to be the rider of course, but come November I get this call that the Mick Doohan team is not going to happen. So I had Briggsy and a few of the other guys ring me up and say, ‘Where does that leave us?’ They had mortgages and young families and they’d made the commitment to jump, so I quickly gathered myself and said, well they’ve got Valentino and as far as I can see they’ve got nobody to run him, so they’ll probably make contact with us, which in due time they did. They said they’d like me to run Valentino in a separate team from the Repsol team. So we had the best team ever – five guys in a separate garage with a factory bike. It was Heaven, we had sponsorship from Nastro Azzurro. We had a whole new group of people and in the next garage there was chaos – there were frames going left right and centre, there were forks, you’d just look over the wall. We had one Japanese with us, Gary Coleman, Briggsy, Bernard Ensio, and we just called ourselves 46 Cranky Lane.”

“Again we were number four on the pecking order but we got on with the job so in all the testing we had the old bike – the bike that Alex Criville had used in ‘99, which had good cylinder porting, very nice, very rideable. Everything was done in Japan, with Honda you really couldn’t touch anything. Valentino was the guy in 2000 taking the risk – he was leaving an Italian team with Italian mechanics to go to a Japanese team with Australian mechanics. Mick never sat down in the garage in his life and I said to Valentino, ‘If you want to sit down, sit on your bike’. You’d have blokes like Rainey grinding away on laps and Valentino would take his helmet off. I’d say, ‘Mate, we don’t take our helmet off here’, and even today he doesn’t take the helmet off. But he wanted a chair, he wasn’t going to not have a chair to sit down, so I said to the boys, ‘If his favourite colour’s yellow, go down to the hardware in Welkom (South Africa) and if you can find a yellow chair it might make him happy’. So we did. All the Italian journalists said about Valentino, ‘One year to learn, one year to win. 125 – ‘96 to learn ‘97 to win, 250 – ‘98 to learn ‘99 to win. 500 – 2000 to learn 2001 to win. And we were able to win the last-ever 500cc title. That was very important to Valentino.”

Valentino Rossi and Jeremy Burgess were such an integral and successful part of Honda’s GP echelon it was inconceivable that the nexus would ever be disturbed, but nothing lasts forever, and in 2003 the winds of change began to infiltrate the previously happy camp when Honda decided to expand the number of motorcycles it made available. “Having delivered three championships, Rossi felt he was entitled to a bit of extra support, and it probably would have been forthcoming but it was never going to be said, so he made the decision to go to Yamaha. I tried for some months to get him to stay with Honda, and he tried for months to get me to go to Yamaha. So eventually I blurted out, ‘If you think it will make any difference I’ll come with you’, and I still remember the smile on his face, and I walked back into the garage and I was trembling and I said to Briggsy and Gary Coleman, Bernard Ensio, “I’m going to Yamaha” and Briggsy said, “Well, if you’re going I’m coming too.”

“Yamaha had not won the championship since Wayne Rainey in ‘92 and here we are in 2004, so you don’t rebuild Yamaha Racing by hiring a couple of Aussies. I took down three mechanics thinking that at least one of them would agree to the terms. I took Gary, Bernard and Alex Briggs and they all negotiated independently. It was reconstructed by Mr Furisawa who was a Mr Fix It, like in any big company, who looked, went back to the board of directors and said we need to spend another X million and it got signed off straight away. He’d fixed their snowmobile problem. He came to Le Mans that year and observed us working and how we worked, which I didn’t know that he’d done, until he enlightened me afterwards. Honda put a ban on Valentino testing for Yamaha until the new year. I went to Malaysia to observe their testing in November 2003 and Mr Furisawa said to me, ‘What do you see?’ I said, ‘Too many computers, I counted 22 guys working on computers when I went into the garage’, and he said ‘Yes, you’re right. Everybody was hiding.’ I said, ‘It’s more practical than that. You get out, you get the information. You respond.’

“When we did start testing in January 2004, and Valentino said to me, ‘You know Jerry, it’s not too bad, but I’m locking the front brake.’ And I said, ‘Oh that’s great’ and he looked at me with the typical blank stare that he sometimes has, and I said, ‘The Brembo brake is the only common part that we had on the Honda that we now have on this bike because we’d gone to Ohlins suspension rather than Showa, and we never locked the brake on the Honda, so I said to the Japanese, ‘Lift the bike up 20mm’. So we got the centre of gravity up on the bike and Valentino said it was perfect. By the time we had the next test we had a 20mm longer swing arm because they wanted to keep everything in that triangle which they loved, and it worked. They had guillotine slides on the fuel injection which is OK on a F2 racing car but hardly what you need on a motorcycle, so I said to them, ‘What we need is to go to butterflies’, and by the time we came to Phillip Island in February we had butterflies. Everything was done right. What they said they’d do they did, and we got to the first race in South Africa and won it.”

“In that year we changed 100 engines, with a total of 40 engines for the season. What we’d inherited was 80 tie-wraps on the bike and by 2005 there was only one tie wrap on the bike, all the connectors were military style connectors rather than big bulbous car ones. What I love about Yamaha is that their problems are your problems, you’re in it together.”

With four more World Championships in the bank, Rossi stunned the racing community with the announcement that he was to leave Yamaha for Ducati, along with Jeremy and most of his crew. And as usual, there was more to the decision than was first apparent, as Jeremy explains. “In Valentino’s case the GFC had come and Yamaha was hurting for money and his salary was way up there. What aggrieved Valentino was that Lorenzo was coming of age and had been promised an increase in salary, which they gave. In Valentino’s case they asked him to reduce his salary so that really got up his nose. He knew if he went to Ducati he’d be number one. He didn’t like the bike from the moment we tested in Valencia and pretty much everything we changed on it didn’t seem to change the character of the bike the way he wanted it. The Ducati was right on the weight limit without a chassis, while the other bikes were too with a chassis which adds 9kg, so it tells you the Ducati engine is 9kg heavier than everyone else.

“It was great to work at Ducati, the people were great, but they’re not very fond of Valentino any more unfortunately. Davide Brivio (Rossi’s manager) would try to find an alternative, which he did by going back to Yamaha via the advertising department to get Valentino back into Yamaha. As much as Valentino probably had to eat massive amounts of humble pie, the advertising people knew that Ago was coming to the end of his ambassadorial role with Yamaha and they’d be looking for somebody else and that Valentino could fill that role for a long, long time. I’m not comfortable with the way we left Ducati.”

It looked like business as usual, back at Yamaha for Rossi/Burgess, and it was until the final race of the 2013 season. “I told him I was there as long as he wanted me. I said to Valentino that I wasn’t going to sign any more multi-year contracts and he seemed to think that was OK, and then he went away – and he’s got an entourage from hell – and somebody from the inner circle said something, and he told me, ‘If I’m going to change next year I may as well change now’. So that was fine, we still get on, there’s no animosity at all.

Not surprisingly, given his 35 years in GP racing, Jeremy has strong views on the future of the sport. He’s particularly concerned at the way Dorna (the commercial rights holder) manipulates the various factors, which makes it extremely difficult for young Australian riders to break in. “I look at racing today and it’s really just donkey racing; controlled engines, controlled ECU, controlled tyres. I hate it because there’s no scope to try something. Carmelo Ezpeleta, who runs the whole show, perhaps the Bernie Ecclestone of Moto GP, he only wants to sell television. Motorcycling is his tool for doing it. It could be yacht racing, it could be anything. It’s really hurting us in Australia now because we can’t get people into the Moto 2 grid, because we have to pay to play, and yet we’ve got Australian champions running around here who can’t get in, and should get in. And I sort of hold Motorcycling Australia and more in particular the FIM to bear for this because they should have been able to foresee this. Some of those teams should be funded to perhaps take the best American, the best South American, the best Australian. It really grinds me and you just can’t beat it. I’ve spoken to everyone but as long as the FIM get their seven million or twenty million a year from Dorna, they don’t seem to have to worry about it, and I don’t think it’s healthy for motorcycling. It’s certainly healthy for auntie and uncle who want to sit and watch the bike races on Sunday night, and it’s a great format, it fits perfectly into an hour, you can see the riders on the bike rather than just a helmet in a car. For people who have no interest in bikes, I’ve noticed over the years how keen they are to watch a MotoGP, but it’s not doing us any good.”