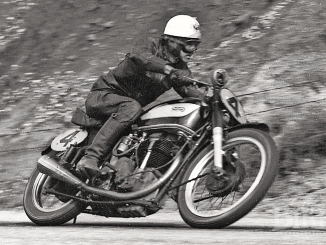

There’s an old saying, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.” It could have been coined to describe Sid Willis, barely five foot (152 cm) tall, Sid was nevertheless extremely fit, a daily swimmer at Ramsgate Baths near his home, and possessed of a fierce competitive spirit. He was also an excellent engineer, his talents keeping many of his rivals’ machines in racing fettle as well as his own.

Born in the southern Sydney suburb of Kogarah on June 10, 1915, Sid’s first attraction to two-wheeled competition was through bicycles. However a serious road accident left him with a shattered leg; so bad that amputation was seriously considered. Luckily however, the doctors at St George Hospital managed to save the limb. Badly scarred but back together, Sid decided that pushbikes were too vulnerable and opted for motorcycles from then on.

Sid was apprenticed as a moulder, specialising in aluminium casting. With the outbreak of WW2 he found himself in a protected industry and spent the period of hostilities at home, although it is doubtful that his severe leg wound would have rendered him fit for active service.

Right from his first brush with motorcycles, Velocettes were his only love. He raced virtually no other marque in his entire career, although he relied on a trusty WLA Harley Davidson and sidecar to transport his racing machinery and provide everyday transport.

The association with Velocette was, for a racer, a shrewd move, as Australia enjoyed quite a privileged position in the eyes of the Velocette management. In the late thirties, while racing in Europe, Victorian Frank Mussett had formed a close relationship with Velocette works riders Stanley Woods and Ted Mellors. With the outbreak of war imminent, Frank made plans to sail for home. Fearing that precious racing parts would fall into enemy hands, the genial head of the Velocette company, Percy Goodman, entrusted Mussett with a large quantity of special DOHC heads, special camboxes and other bits, as well as one of the rare works 500 KTT models. Mussett arrived back in Australia in the nick of time, and according to Goodman’s wishes, many of the parts found their way to local Velocette racers, including Sid.

Back to the tracks

When local racing resumed in 1946, Sid was right there with all the other action-starved racers at Mount Panorama’s Easter Victory TT races at Bathurst, 200 kilometres from Sydney. His mount was his 250 Velocette, a sleeved-down 350 KTT still running the SOHC head, which he had originally purchased from the pre-war star Don Bain. At Bathurst, Sid was beaten for the Lightweight TT by Ted Carey; a contemporary in more ways than one. Ted was also an expert in casting and had made patterns to cast his own pistons, DOHC heads and camboxes. Carey’s form of heat treatment was to place the finished article over a saucepan of boiling water and allow the whole plot to cool slowly. Crude, but demonstrably effective!

Sid went searching for more speed. Although perennially short of money, he arranged to buy an ex-works DOHC head and cambox from Mussett, which he fitted to his own engine. The completed Velo was then loaded onto the Harley outfit and off they trundled to the Heathcote Road – Sydney’s unofficial tuning strip. To his delight, he saw an extra 1,000 rpm on the rev-counter, which he reckoned equated to ten miles per hour down Conrod Straight at Mount Panorama.

Sure enough, Sid trounced his rivals at Bathurst in 1947 to take the first of his four victories there. He repeated the feat the following yearbut lost out to Harry Hinton (riding Tom Jemison’s Velocette) in 1949. But if Sid’s stature as a rider was growing rapidly, so was his reputation as a tuner. By now he was working for himself, producing a constantly increasing array of racing engine components from his minuscule workshop behind his parents’ house in Carlton.

This tiny structure housed a small lathe and a home-made furnace, where he cast not only his pistons (many of which still pound up and down in Historic racing machines today), but carburettor bodies, crankcases, barrels, heads…and even a set of teeth! Dismissing a local orthodontist’s quote as outrageous, Sid fashioned his own fangs to fit his gums, and polished them to a mirror shine. Vintage stalwart Maurie Pearson recalls the day when Sid turned up for a scramble at Heathcote wearing his new cast-alloy choppers. “He looked horrible! His mouth was all black from the aluminium. Everyone thought he had pyorrhoea!”

The teeth were soon discarded for factory jobs, but it showed that Sid would never buy anything until satisfied that he couldn’t make it better himself. In the early 1950s, Sid even constructed his own desmodromic cylinder head. Starting with a SOHC KSS head, he machined off the cambox and cast his own to house the desmo valve gear. With no facilities to forge rocker arms, Sid applied his usual ingenuity and fabricated his own, using pieces of Sidchrome spanners silver-soldered together! Despite spinning to 10,000 rpm, the springless engine was no faster than his own DOHC model, and the homespun rocker arms were prone to breakage, so the project was abandoned.

It was about this time that Sid managed to convince P&R Williams, the Velocette agents in Sydney, to part with the Mark 8 KTT which had graced their window for many months. The special ‘clearance’ deal once again left Sid penniless, but now armed with a very potent piece of machinery.

With the new 350 to complement his 250, Sid continued on his winnings ways in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia, clocking up huge distances in a time when interstate highways were little more than rough country roads. When interstate, his rivals in the 250cc Lightweight class were invariably Velocette-mounted as well – a battle as much of prowess in the workshop as riding ability. South Australia’s Les Diener was always a tough man to beat, initially on his very fast ohv MOV and subsequently on the first of his self-built DOHC models. Sid claimed the Victorian GP at Ballarat on New Year’s Day, 1949, defeating Diener and Victorian Velo star Bob Elsbury. At the other end of the year, on Boxing Day, Sid won the 250 cc Australian TT – the official Australian championship – at Nooriotpa, on Diener’s home patch. Les had his revenge a few months alter at Easter 1950, when he won the Lightweight at Bathurst, pushing Sid into third place behind Hinton. In October, Sid won the Queensland Lightweight TT at Lowood. He returned to the same circuit in June 1951 to take his second Australian 250cc TT, a few months after winning Bathurst again. After cleaning up the Lightweight for the fourth and final time at Btahurst in 1952, the Willis/Denier battle recommenced at the 1952 Australian TT at Little River, west of Melbourne on Boxing Day, but Les’ machine failed to go the distance and once again it was Sid who took the title.

Sailing for Mona

In 1953, at 38 years of age, Sid took the biggest decision of his life – to take the plunge in Europe. This was prompted by discussions with Tony McAlpine, the flamboyant NSW rider who made his name hurling big Vincent V-twins around with great success.

McAlpine already had three continental seasons under his belt and was well versed in the art of survival on the European privateer circuit. Accompanied by Tony’s wife, the pair set sail, taking with them Sid’s dohc 250 which still looked decidedly pre-war with its rigid frame and girder forks. Their accommodation was a 1938 Fordson van with a sixteen-foot caravan, housing not only the humans but Sid’s Velo and McAlpine’s 350 and 500 Nortons.

The first outing was on the fast and notoriously rough Mettet public roads circuit in Belgium, where Sid’s machine literally fell apart beneath him. A few weeks later at Zandvoort in Holland he impressed by finishing third in the 250 race behind two ex-works Moto Guzzis, but it was by now obvious that the Velo was seriously deficient in the handling department.

After the frugal existence on the Australian circuit, life on the Continent seemed positively luxurious. Upon arriving at each venue, Sid would start work on the bikes while Tony did the rounds of the trade paddock, invariably returning with a good haul of the sponsored items – chains, tyres, spark plugs, lubricants and fuel, as well as other brand new bits that were virtually unobtainable back home.

The big one, the Isle of Man TT, was next on the schedule, but beforehand Sid arranged to part with what was left of his savings to buy a new frame from Douglas St Julian Beasley, or Doug Beasley for short. These frames were lightweight twin-cradle affairs using Velocette telescopic forks and Armstrong rear dampers. Beasley had constructed around half a dozen examples and they performed very well, and in any case it was obvious that Sid’s ancient chassis would never cope with the rigours of the Island. Into the new frame, Sid installed the engine, gearbox and wheels from his own machine, and set sail across the Irish Sea.

To assist in the daunting task of learning the 38-mile course, fellow Sydneysider Ernie Ring, who was now a member of the illustrious AJS/Matchless factory team, arranged for Sid to borrow his 350 AJS road bike. This meant 3am starts, for the AJS had to be returned so Ernie could conduct his own reconnaissance. Sid managed just nine laps before official practice began. The 250 TT was to be held over four laps of the full Mountain circuit and had attracted 38 entries. These included six of the formidable Moto Guzzi horizontal singles – works bikes for Fergus Anderson, Tommy Wood and the Italian Lorenzetti, and three in private hands. There was also a pair of works DOHC NSU twins for Bill Lomas and Werner Haas, two works triple-cylinder DKW two-strokes, and a big private entry mainly aboard Velocettes, Excelsiors and Nortons.

A glorious debut

Several of the star names eliminated themselves in practice accidents, including Lomas and DKW’s Felgenheier, leaving 31 riders to face the unusual (for the TT) massed start. After days of sunshine, the fickle Manx weather typically closed in just hours before the start of the race, forcing a 60-minute postponement. Although thick mist still covered half the circuit, the event finally got under way, and by the end of the first lap Anderson led, followed by Haas and the veteran Siegfried Wunsche on the remaining DKW. Sid lay eighth after an impressive first lap of 76 mph. By the third lap, visibility across Snaefell Mountain was down to 100 yards, but Anderson pressed on, barely lowering his speed as he had Haas just seconds behind him. And at the end of the lap, Sid’s name crept onto the hallowed Leader Board opposite the grandstand – 6th place at an average of 76.26 mph. Into the final lap and Anderson held off Haas to win by 17 seconds, but Sid was putting in a big finish as well. In the closing miles he urged his Velocette in front of Wood’s works Guzzi to come home a gallant fifth in 2 hours 0 minutes 8 seconds, the second private owner to finish after Arthur Wheeler’s Guzzi. It was the first time he had ever worn gloves while racing!

From the TT it was on to the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, but it was a tragic day for Australia when Ernie Ring crashed his works AJS ‘Porcupine’ twin on the opening lap of the 500 race and was killed instantly. By now Sid’s thoughts were turning to home, but he stuck to his schedule of nine meetings in order to secure much-needed start money. At the West German Grand Prix at Schotten he finished an excellent eighth behind a horde of works NSU, DKW and Guzzi machines. In the Italian Grand Prix at Monza he came home 14th in the 250 race, before putting in a few start-money laps in the 350 event. He selected a ‘retiring point’ with a good view of the circuit and it wasn’t long before Tony McAlpine and Victorian Gordon Laing arrived to ‘retire’ as well. Sid had brought along his stopwatch, Tony had his pipe and tobacco, while Gordon had his camera. By all accounts a very pleasant afternoon was had by all.

Sid’s last scheduled start in Europe was at the notorious Freiburg Hill Climb in Germany; a frightening and lethal course of 177 bends and corners lined by trees and sheer drops. In practice Sid fell off in a big way and knocked himself about quite badly. He also severely bent his new Beasley frame, rendering it unrideable. Nevertheless, there was sixty pounds starting money waiting and Sid needed it, so he managed to borrow a 7R AJS to complete his runs.

Heading for home

He and the McAlpines sailed for home aboard the Strathmore in November. Ten months after he had left home with his return passage paid and sixty quid in his pocket he arrived back with half the cash and 28 brand new Dunlop racing tyres. By virtue of his two points for fifth place in the Isle of Man, he had finished 13th in the World Championship and scored Velocette’s only points to put the marque fourth in the 1953 250cc Manufacturer’s standings.

Back in Carlton, Sid slipped naturally back into his former lifestyle. Physical fitness, and swimming in particular, had always been very important to him. Every day, he would ride the Harley outfit to nearby Ramsgate Baths. It was not uncommon to see Sid, bronzed and leathery, sitting on the side of the pool, discussing pistons and the like with customers who realised this was the easiest way to see him. In later years he excavated and built a swimming pool which ran virtually fence-to-fence in the tiny Carlton back yard, although this meant removing the set of parallel bars he had built from waterpipe many years earlier. But the little workshop remained, and from it emanated the parts that kept many of Australia’s fastest racing engines at the top. Sid had little place for nostalgia; his miraculous creations were ruthlessly recycled once they had served their purpose. The chimney from the furnace was held in place by the magnesium mudguard brackets from the ex-Ted Mellors works 500 Velocette, while another famous feature was the blackboard inscribed “Days to Bathurst”. This was mounted above a shelf containing scores of pistons in various stages of finish. Somehow everybody got their job, even those who had no money to pay for it.

Although he never won again at his beloved Bathurst, Sid remained a formidable competitor to the end of his racing days. In 1958 he had the 250 GP shot to pieces after leading the whole way, when the Velo broke a timing side mainshaft as he received the yellow flag to start the last lap. The year before he had chased home the fully-streamlined NSUs of Jack Ahearn and Jack Forrest, and in his last year, 1960, he finished a credible third in the Australian 250 TT behind Eric Hinton’s NSU and Kel Carruthers’ 250 Norton. Until the Mount Druitt circuit closed in November 1958, Sid was virtually unbeatable in 250 races. Eventually he sold the last of his special engines, a 74mm x 58mm double knocker, to buy a television set! After being lost for many years, the engine resurfaced in Tasmania around the turn of the century.

Sid died on May 10, 1984, aged 69. He had been diagnosed as suffering from cancer, and an operation on this condition resulted in a fatal heart attack. He never married and lived at his parents’ home in Carlton for his entire life. In Sid, Australian motorcycling lost one of its all-time greats, not just in riding ability, but in his unfailing devotion to the sport.

Words: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Dennis Quinlan, Tom Perry, Graham Roberts, Gwen Bryen, Byron Gunther, Keith Ward.