From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 74 – first published in 2018.

• Story Peter Laverty and Tony Sculpher • Photos Tony Sculpher and Jim Scaysbrook

Honda had, of course, made a 4 cylinder 350 prior to the release, in 1972, of the CB350F. That one, officially the RC173, was ridden with much success by a certain Mike Hailwood, who took it to the 1966 350cc World Championship, winning six of the eight Grands Prix.

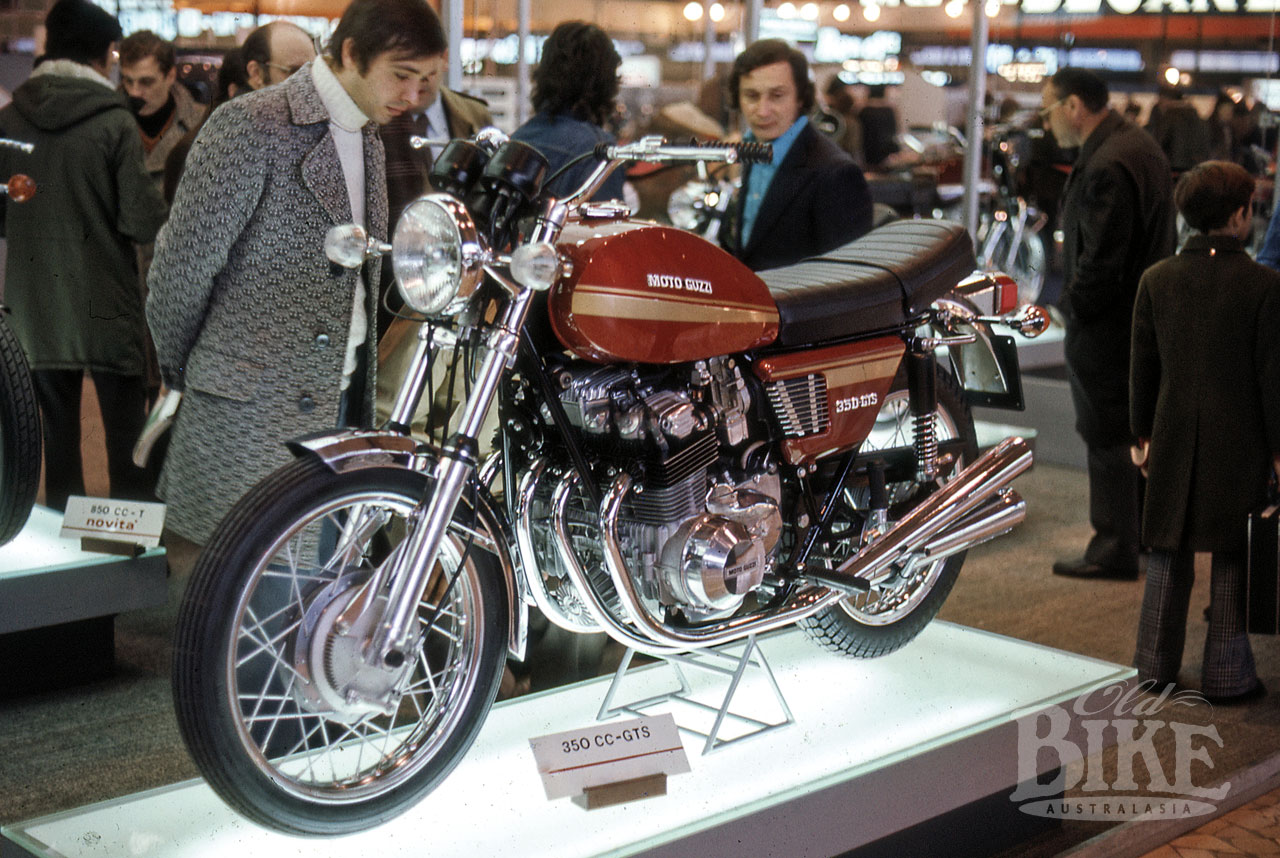

But the RC173 had little in common, apart from the brand on the tank, with the machine announced in July 1972. At first creating widespread interest, the 350 being visually similar to the popular CB500 four, enthusiasm waned somewhat as the first test rides took place. One magazine tester lamented, “Honda’s new 350cc four is easily the heaviest, most expensive thing in its displacement class, and a list of others capable of going a standing-start quarter quicker than the Honda would be a lot longer tally of those that won’t…Honda shouldn’t even have contemplated building a four-cylinder 350…All they can hope to do with the 350 Four is lure buyers away from their own 350 twin.” So, overweight, over priced and under performing? Sounds like a recipe for disaster.

Looking back 46 years, it is true that the 350 Four was anything but a showroom success, and that its twin-cylinder counterpart continued to rein as the largest-selling motorcycle in the USA for several more years. But today, we perhaps see the Four for was it is, or rather how (and why) it was conceived. In the face of increasing four-stroke opposition from the other Japanese manufacturers, Honda wished to demonstrate in no uncertain terms that they were still king of the camshaft brigade. When they put their mind to it, they could make anything, and the 350 Four was the smallest capacity four cylinder motorcycle ever to enter mass production. And rather than satisfy a known market, why not create one? That last question was answered by the model’s embarrassingly brief production run of less than two years. Curiously, the model was never released in the UK, but given the sales figures from other world markets, it probably wouldn’t have worked there either.

The smallest Four used an engine that had visual similarities to the CB500. Against current thinking, it was under-square, with a bore and stroke of 47mm x 50mm, and a 9.3:1 compression ratio. The familiar chain drives the single camshaft, but there is no external adjustment for that chain. The crankshaft ran in five plain bearings, with a Morse chain primary drive running from the centre of the crank to the clutch. Four 20mm Keihin carburettors fed the mixture, which exited via four separate exhaust pipes with tapered megaphone style mufflers. Those components, like the ones found on big brothers, had a fairly short life before surrendering to corrosion, collapse, and replacement, usually with an after-market four-into-one system.

Like its siblings, the smallest Four stuck with points rather than move to the new-for-the era CDI systems. By allowing each coil to lose a spark on the exhaust stroke, there was no need for a distributor to send the spark to the correct plug.

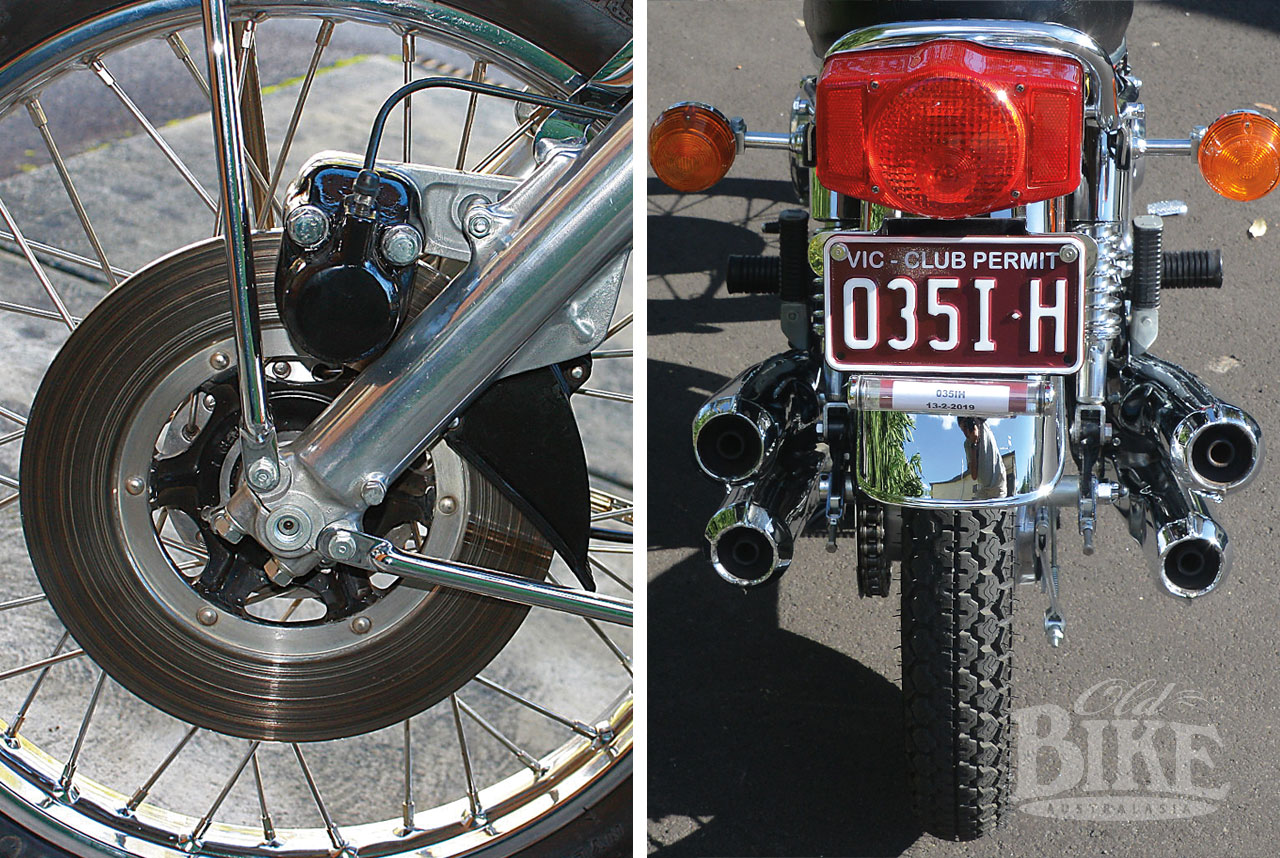

Unlike the 500, which used a duplex cradle frame, that on the 350 was a single down tube affair, which split into a loop at the bottom to allow the oil filter to poke through. Up front sat a 254mm single disc brake, which by all accounts worked very well, with a single-sided hydraulic pad working against a fixed pad via a flexibly mounted caliper, as on the other ‘fours’. A major complaint on the CB500 was dramatic loss of efficiency in the wet, and to this end the 350 was fitted with a plastic shield at the rear of the rotor to prevent water running onto the disc. A 152mm drum provided the rear stopping. The suspension was fairly typical of the era, with a telescopic front fork with one-way damping, and a pair of rear suspension units that seemed devoid of efficient damping. All the bodywork on the 350 was unique to the model. Total sales world-wide amounted to under 80,000.

Compared to other ‘fours’, the CB350F is quiet, almost disturbingly so. Air reaches the carburettors via twin air boxes with a rubber inlet pipe under the seat, and there is obviously plenty of baffling inside the mufflers. Testers complained that the seat was too hard, and that the footrests were a bit too far forward – something that may have been alleviated by the use of lower handlebars than the semi high-rise style fitted as standard. But there were many nice touches, such as the lockable seat that kept the tools safe from prying hands, and the incorporated helmet lock. Both the air filter and battery were easy to service.

“Smooth” was the most common descriptive used of the 350 Four. Not less a figure than Soichiro Honda himself declared it to be “the finest, smoothest Honda ever built.” It certainly had an appetite for revs, being red-lined at 10,000, but with minimal power below 5,000 rpm. There was also a vibration period between 5,500 and 6,000 rpm, which is precisely where most time is spent in traffic, causing the mirrors to vibrate with associated loss of rear vision.

The 350 Four did not go on sale in Australia until early 1973, and at $1025 it had a hefty price penalty compared to other 350s, such as the RD350 Yamaha at $859. But the newest four did offer a high degree of sophistication, plus the kudos – perceived or not – of those four gleaming pipes. It’s true that few found homes here, and the overriding reason for that was the competition the Four suffered from its own brother, the 325cc CB350 twin, which was a damned good bike, lighter, nearly $200 cheaper, and quicker.

The CB350 Four shared virtually nothing with the CB500 (which shared virtually nothing with the CB750) so it was expensive to tool up for, and with such a short production run, almost certainly unprofitable. In most schools of thought, apart from Honda’s, interchangeability of parts between models, and shared manufacturing platforms, were the way to go –the CB250/350 twins exemplified this thinking. But perhaps the shortcomings of the 350 spawned what is generally held to be one of Honda’s greatest models of the ‘seventies – the handsome, fast and light CB400F. Now that’s quite a legacy.

Soichiro’s favourite Honda – the CB350 Four

• Story Tony Sculpher

The four cylinder Honda 350 cc models were manufactured between 1972 and 1974. The first model was the CB350F and came in three colours – (the most popular) Flake Matador Red, Candy Bacchus Green and the not so popular Custom Silver Metallic. All three colours featured White and Orange stripes. For 1974 the CB350F1 model was offered with no changes apart from new paintwork named Glory Blue Black Metallic and with gold stripes. My limited research tells me that the Glory Blue Black Metallic colour was sold mostly for the North American market.

The CB350F models all featured conventional Honda technologies and styling for the early 1970’s era. The frame, suspension, wheels, lights, instruments and brakes were all conventional Honda components but the tiny four cylinder air-cooled engine was the jewel in the CB350F’s crown – a very smooth unit. To quote the popular description of the time “ it runs like a Swiss watch”, and this was the real attraction of the CB350F and this charm endures to this day.

The 347 cc engine features a single overhead camshaft operating two valves per cylinder; a conventional wet plate clutch and a five-speed transmission. The crankshaft was supported by shell bearings – a departure from the previous CB350 twin models which used ball and roller bearings. The external finish of the aluminium engine castings took the CB350F to a new height of finish when compared to the previous model. The Japanese had already been experts at die casting techniques for many years and this experience was on display.

The weight of the CB350F was its Achilles heel – a whopping 19kg more than the CB350 twin. That’s a lot of extra weight for a 350 cc motorcycle to bear. The engine output was 2 hp less that the twin, and this all added up to making the four slower in acceleration and in top speed. The standing quarter mile time was 15.61 seconds with elapsed speed of 131.9 km/h, against the twin’s 15.3, although these figures varied greatly according to which magazine did the test. This lack of performance is most probably why the CB350F was not ever imported to the United Kingdom market. The surface area of all the multiple engine components and the resulting friction was the culprit. This engine was a compromise of performance against life. But the easy to ride nature plus the sedate and smooth power delivery of the CB350F were very good reasons why it was Mr Soichiro Honda’s favourite Honda model.

The four separate exhaust header pipes and mufflers with bright chromium plating were unique to the CB350F. They were tucked alongside the engine cleanly, but for the real racers of the time – a four-into-one was the only option to raise the ground clearance and to produce that beautiful sound. The shape of the mufflers is actually reminiscent of the megaphones utilized on the exotic multi cylinder Honda racers of the early to mid 1960s. Should you get the chance, stand behind a CB350F when it is at idle (or any CB500 or CB750 four of the early 1970s), and listen to the sound when it accelerates away from you. They sounded like nothing else. During the 1970s, owning any Honda four and being a member of the Honda Four Club meant that you were in exclusive company.

The CB350F featured minor changes between the markets where they were sold. The main markets were Japan, North America, Germany, France, with other markets supplied with “European Direct” and “General Export” models, Australia receiving the General Export model. The changes were all cosmetic and limited to the speedometer (either MPH or Km/H), tail light (three different types), indicator lamps (two different types), chain cover (black or chrome), and the rear vision mirrors.

Living in the ‘70s

My mates and I evolved through the Honda models as schoolboys, starting with the single cylinder trail range, graduating to the CB350 and CB360 twins with the one lone CB350F in the crew. Unfortunately our mate rode his CB350F slowly like an old man (sorry) which created a lasting and poor impression to most of us. We affectionately nicknamed the CB350F “the slug”. As budding road racers on our Honda twins, we added two-into-one exhausts and raised foot pegs to improve ground clearance – we could improve the breed …. but these smaller mid-range Hondas were only one step up the capacity ladder to the multi cylinder engines we dreamed of – CB400F, CB500 and CB750s followed, before we purchased those open class DOHC offerings manufactured in Kobe.

In 1975 the sedate CB350F evolved into the exciting CB400F – complete with that stylish and exotic exhaust system featuring the four-into-one header pipes and a single muffler – functional both for aesthetics and for extra ground clearance. Marketed as the “European riding position”, the low handlebars and rear set footrests coupled with the slim seat and large fuel tank all meant business – a Café Racer – and it was made in Japan! The engine’s exterior featured minor changes to go with the increase in capacity to 408 cc (Japan’s market model was 398 cc to meet their registration laws). Lighter weight and more horsepower gave what we saw as a stodgy old four a new life. There is only an extra 61 cc and the four into one exhaust, plus a six-speed gearbox, but I suspect there are other changes to the camshaft and the combustion chambers to substantiate the performance difference over the CB350F. A well ridden CB400F offered only little resistance to the dominant Yamaha RD400 in production racing.

My CB350F

This particular CB350F is a USA model, complete with the high USA specification handlebars, speedometer in MPH, and the large tail lamp. It was imported into Australia during late 2013 with approximately 14,000 miles on the odometer. This Honda was purchased by a private collector based in Sydney, and he displayed it unregistered in his basement along with his other collectable motorcycles. Despite being a low mileage example, the new owner proceeded to spend a large amount of money on refurbishing major components such as the tank and side covers, seat, wheels and the exhaust system. Consequently he came under pressure to reduce his collection, and I was able to purchase the Honda. Unfortunately the new paint on the tank and side covers did not match the original Flake Matador Red on the fork covers, so the entire bodywork was repainted to produce the result we see now. The pin stripes were hand masked, such were the skills of the painter. Also completed were new chrome plating on the shock absorbers, both mudguards, tail lamp housing, rear brake lever and numerous bolts. New zinc plating was completed on most of the bolts and fasteners. Other smaller missing components including a Yuasa battery and genuine handlebar grips were also sourced to make this CB350F complete as it had left the showroom. The genuine Honda CB350F Owner Manual proved quite expensive to source.

Riding the CB350F

After all these years, purchasing a CB350F for my humble collection was an admission – I really do like the tiniest Honda four, and I always loved the styling and that beautiful exhaust system. The handlebar mounted warning light display came straight from the fabulous CB750. My everlasting impression was of a poor performer, but riding the CB350F for the first time in over forty years showed me that I had let my youthful naivety cloud my judgement. The CB350F does actually perform very well; not quite as fast as a CB350 twin, and nowhere near the Yamaha RD350 or Suzuki T350 two strokes which fought out production racing of that era. Take the tachometer above 6,000 rpm and the little Honda really does start to produce some power. It seems as if it really wants to stay there at these higher revolutions and the power delivery is constant right up to the red line.

The CB350F is just too easy to ride, and it rides comfortably and smoothly; perfect for those who have returned to motorcycling after many years and are not so confident with their rusty riding skills. No-one should ever discount taking a CB350F for a long haul trip, such is the comfort for even an older motorcycle (albeit, sedately) approaching fifty years of age; a perfect mount for collectors and enthusiasts who are looking for a totally reliable and comfortable club motorcycle that will get you there and back again, many times. Comfortable two-up riding is a bit of a squeeze.

As was the standard practice during the 1970s, change those tyres for a good mid-range performance tyre (Dunlop TT100s look good). And change those “pogo” stick shock absorbers – they look great at a motorcycle display for accuracy and photographs, but are not recommended for any action approaching those hard cornering antics of your youth. The CB350F is quite easy to clean and groom despite the four exhausts – such was the simplicity of the design of the era. It is a pleasure to clean and polish the CB350F, especially with all that bright chrome plating. I never tire admiring those big bike features – a true example of good design and execution.

Specifications: 1972 Honda CB350 Four

Engine: Single overhead camshaft, four cylinder, two valves per cylinder, air cooled.

Bore x stroke: 47mm x 50mm

Capacity: 347cc

Compression ratio: 9.3:1

Power: 34hp @ 10,000 rpm

Torque: 27.2 Nm @ 8,000 rpm

Ignition: Points, battery and coil.

Carburation: 4 x Keihin 20mm

Wheelbase: 1351mm

Weight: 179kg

Fuel capacity: 14.7 litres

Top speed: 98 mph.

Wheels/tyre: Front 300 x 18, Rear 3.50 x 18.