A Latin alternative to the Triumph Bonneville? It sounded like a good idea at the time…

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

It’s fair to say that upon its release in 1969, the Benelli 650 (it subsequently acquired the Tornado and 650S designations) did not exactly cover itself in glory. For one thing, the buying public had become increasingly impatient for even a glimpse of the production version of the machine that had first been touted back in 1967 at the Milan Show. Had it appeared on schedule, the Benelli may well have immediately done what it was supposed to do; eat into the traditional British 650 twin market. But by the time it appeared, that market had not just been eaten into, but mauled ferociously by the BSA and Triumph triples and the Norton Commando, then finished off by the ground-breaking Honda CB750.

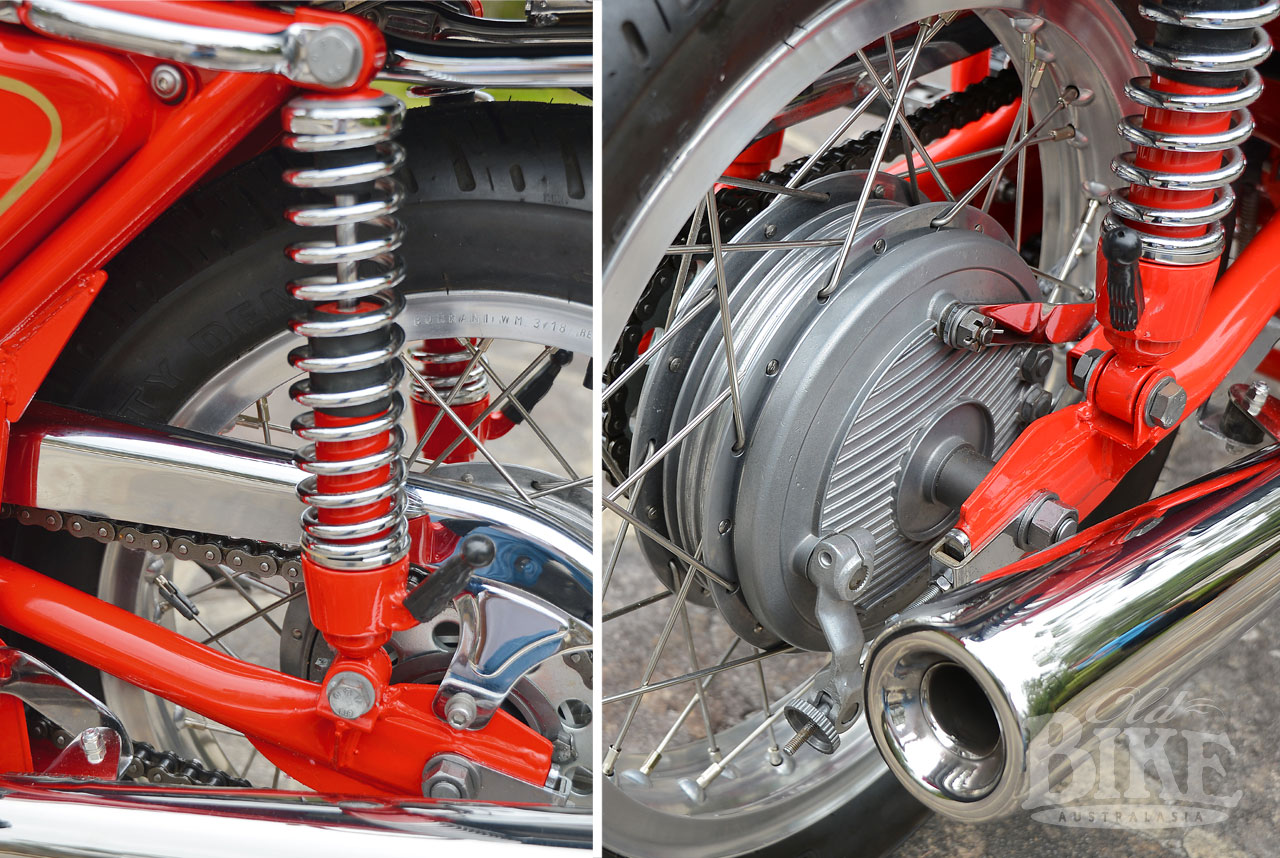

The Benelli of 1969 appeared caught in a time-warp, particularly in the styling. The frame bore more than a passing resemblance to the neat Rickman Metisse, which was no bad thing, but closer inspection revealed a skin-deep beauty. Even the cycle parts – tank, seat, mudguards and side-covers, looked like they could have come straight from Michenhall Brothers Avon works. The seat was a Metisse doppelganger too. But it did have Marzocchi front suspension (in that company’s fledgling days), Ceriani rear shocks and very aggressive looking Grimeca brakes – a double-sided single leader up front and a single-sided rear. Later models switched to stainless steel for the mudguards, a feature that Benelli adapted across most of its range.

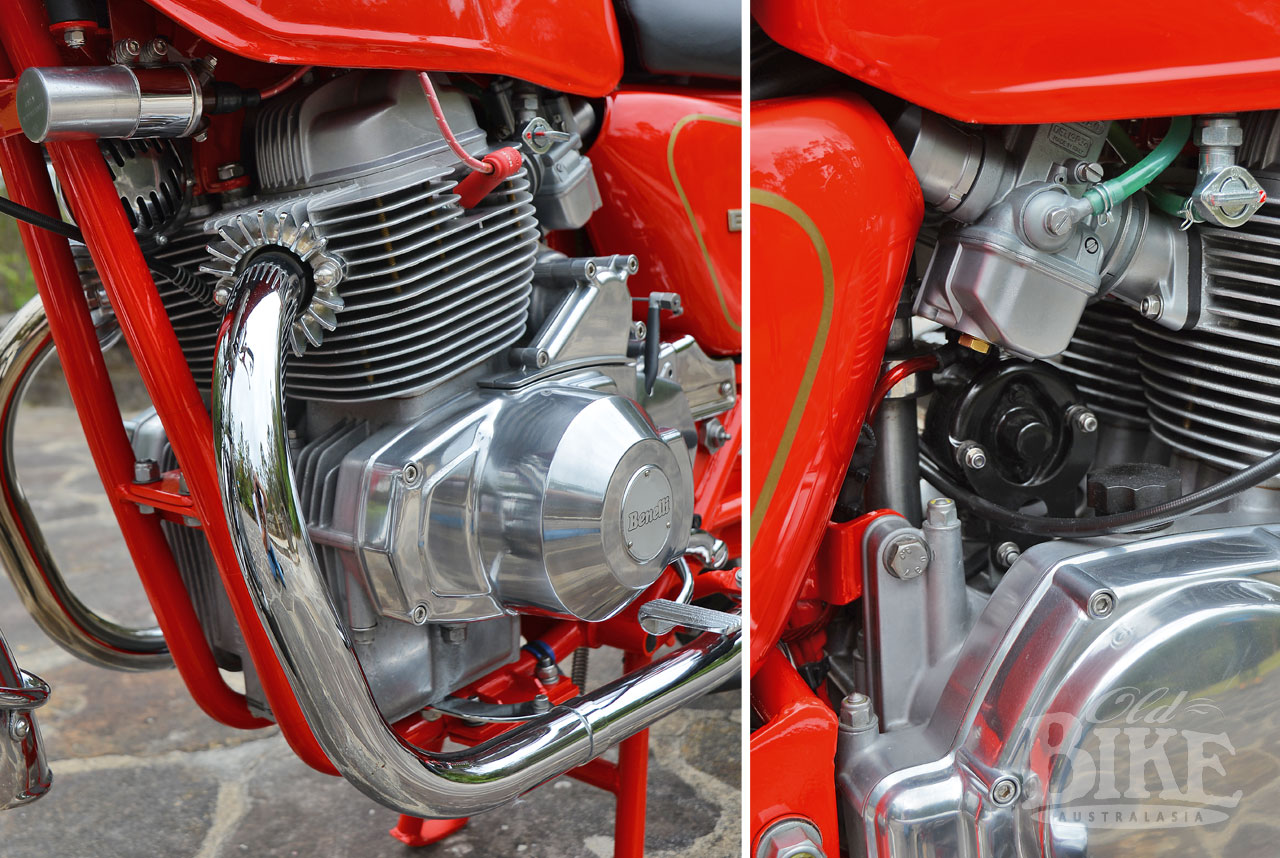

But like any motorcycle, the powerplant was the focal point of the Benelli 650, and this parallel twin was the creation of Piero Prampolini, Benelli’s head of design and the man responsible for the company’s successful four-cylinder Grand Prix racers. His racing background had instilled in Piero a compulsion for an oil-tight engine and as few external lubrication-carrying pipes and tubes as possible. His design incorporated a three-litre sump integral with the horizontally-split crankcase, with the crankshaft, camshaft and gearbox mainshaft all sitting in the same plane, Japanese-style, in ball and roller bearings. A robust flywheel sat between the two centre main bearings. In the days when over-square engines were still regarded with suspicion in some quarters, the Benelli went the whole hog with 84 mm bore and 58 mm stroke, allowing for valves of 38 mm inlet and 35 mm exhaust, although the valve size was limited by the squish-band incorporated into the combustion chamber design. The vastly over-square concept allowed for short and light conrods, keeping the overall height of the engine down. Twin 27 mm Dell’Orto carburetors supplied the mixture.

Separating the Benelli from its parallel twin ilk was the fact that the engine rotated backwards, that is to say, in the opposite direction to the wheels. Prampolini’s reason for this design quirk was that piston-to-cylinder friction is greatest at the rear of the cylinder, so by reversing the rotation this pressure-point, and source of heat build up, would be facing forward, directly in the air stream, and hence subject to maximum cooling. The gear primary drive made it a simple task for an intermediate cog to reverse the direction onto the output shaft and thence to the rear wheel.

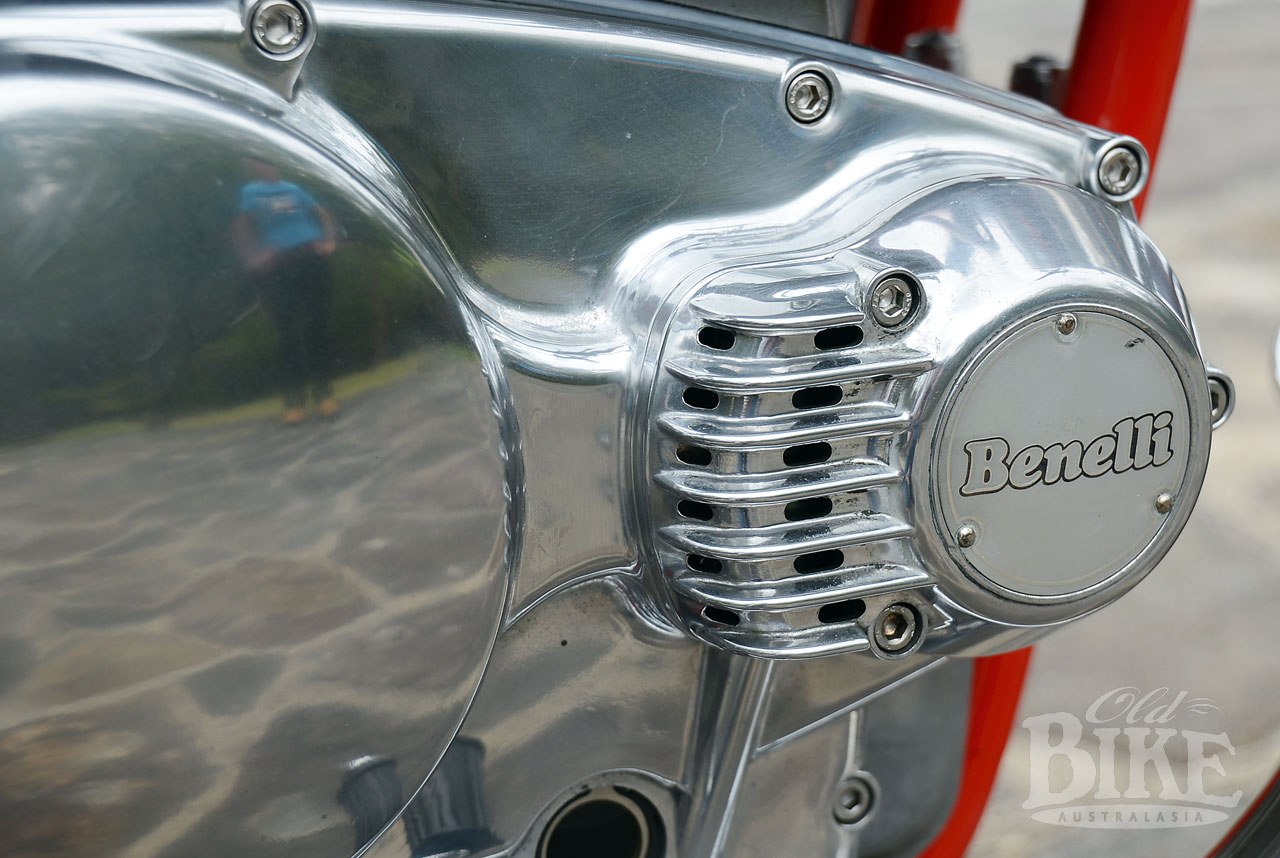

A five speed gearbox (with the change on the right, one-up and four-down in British style) with a conventional-style multiplate wet clutch made up the transmission, but for some curious reason there was an inordinately large gap between first and second, making for a temperamental situation in traffic. Silently-operating helical gears drove the clutch and the camshaft. Lubrication was controlled by a single-stage gear-type pump located below the camshaft, drawing oil from the crankcase through a fine mesh strainer. High-pressure oil was delivered to the crankshaft, camshaft, pushrods tappets and rocker arms with a separate, replaceable paper filter in line to keep the oil as clean as possible. Although a hefty Bosch 180-watt generator sat atop the crankcase, driven by a belt, there was no electric starter on the original model. Conventional battery and coil supplied the sparks and the lighting.

Fast forward a couple of years and Benelli had learned a few things. Road test reports of the original model complained of annoying vibration and dodgy handling – the former exacerbated by an overly-restrictive exhaust system. The bike was now referred to as the Tornado, and virtually everything had come under close inspection or been completely revised. The engine retained its 84 x 58 dimensions, but now breathed through 29 mm Dell’Ortos (with square slides) that incorporated a new choke system to make starting easier, which was still accomplished by foot and not by finger.

But despite the Metisse-like frame, it was the handling that had been heaviest criticized on the 650, and this was not so easy to rectify. Basically, the engine sat too high in the chassis – the crankshaft centres fully 10 cm above the line through the axles. According to road testers, handling that was acceptable around town became extremely ponderous when the 650 was opened up, due in large part to the overly-high centre of gravity. Surprisingly, and apparently in the interests of styling alone, the revised model that appeared as the Tornado dispensed with the side frame members running from above the swinging arm pivot to the top frame tube. Suspension at both ends had been stiffened considerably, leading to more precise handling at the expense of ride comfort. But at nearly 220 kg (480 lb) the Benelli was always going to test any suspension set-up to the limit.

Some of the quirkiness of the original switchgear had been eliminated in the second version, notably the positioning of the ignition key, but the main switch unit was still the quaint looking CEV unit found on everything from scooters up in Italy, and a bit oldy-worldy for a heavyweight thoroughbred. There were still no turn indicators fitted. The lights were totally rethought and now considered quite adequate. What wasn’t adequate or in any way satisfactory was the lack of any air filtration – unthinkable on a motorcycle supposedly in competition with Japan’s finest. Apart from the intake roar, the effects on engine life were a definite worry. Complaints also came regarding the stiffness of the throttle action both in traffic and on the open road.

In its third incarnation, the Benelli was now officially the Tornado 650S, and had achieved the distinction of the electric starter it should have had all along, albeit with the penalty of a rather bulbous extra casting on the left side of the engine. The starter motor sat where the DC generator had previously been, and electric power now came from an alternator mounted on the end of the left-side crankshaft. A side-effect was that to set the ignition timing, the alternator had to be removed to allow a degree wheel to be placed on the crankshaft. This was a most Italian-like method, considering that Japanese bikes simply used timing marks engraved into the rotor and stator.

In this, the Benelli’s ultimate specification, power was listed as 57hp @ 7,400 rpm – hardly in Triumph Bonneville territory but quite adequate, really. Right to the final model, the problem with the internal gear ratios was never addressed, and continued to be one of the machine’s major drawbacks, especially around town. It required a conscious effort on the rider’s part to change down no lower than second unless speed had dropped to walking pace, or the rear wheel would clatter and lock.

This is not to say that the Benelli was a failure. For a start, it was Italian, and that counted for quite a bit amongst the enthusiasts. However that word enthusiast carried its own implications – virtually by definition an enthusiast’s motorcycle was one that was purchased and ridden by someone who was a motorcyclist through and through. Equally apparent was the fact that boat-loads of CB750s and Z1s were being purchased by non-enthusiasts, although many, smitten by the experience of ownership of a Japanese jet, would subsequently become one. Eventually, Benelli itself capitulated and joined the multi-cylinder ranks; first with a clearly Honda-inspired 500 cc four and in 1975 with the ground-breaking 750 Sei six-cylinder job.

Fortunately, enthusiasts bought motorcycles for reasons other than value for money. In fact, the financial penalty for falling in love with one of the more obscure brands was often considerable, but the panache, the kudos and the pose-value was easily justifiable.

Benelli Down Under

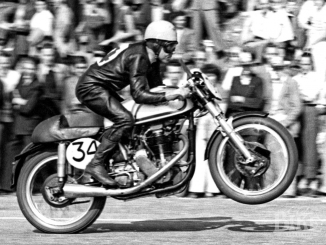

Despite Kel Carruthers winning both the 1969 Isle of Man TT and the 250 cc World Championship for Benelli, the marque struggled to get a foothold in Australia and went through a number of distributors in rapid succession. The first 650s, and only a handful of them, arrived here in 1971, the last three years later, by which time the price had settled at $1650 exclusive of registration and third party insurance (in NSW). You could have a CB750 for the same outlay. A 3-month or 3,000 miles warranty was offered.

Our featured machine, a 1971 model 650S was sold new by Taylors International in Gouger Street Adelaide SA to Anton Van de Laar is now owned by Dave Aquilina, who has carried out a meticulous restoration, in his words “ground-up, nut and bolt with absolutely no compromise”.

“The bike only had 20176 original kilometers and was a one-owner, properly stored for thirty years,” says Dave. “Every seal, gasket and rubber was replaced. The cylinders were lightly honed and given new rings which was all it needed. The clutch plates were resurfaced in Kevlar by Gowenloch. Phil Hitchcock at Road and Race respoked the rims and replaced the wheel bearings and tyres as well as rebuilding the shocks front and rear, and he also supplied many hard to get parts. The seat was done by John Moorehouse in Queensland, who even went to the trouble of screen printing a copy of the original Benelli logo on the back of the seat. Peter Boris took care of the Veglia gauges. Conti stainless look-alike mufflers with standard Benelli mounting brackets came from Overlander in SA – as originally supplied the mufflers were an odd-looking chopped megaphone style, more two-stroke oriented. The restoration took 500 hours over eighteen months and I enjoyed every minute of it. The cost of the restoration was around $10,000.00 not counting the purchase price of $5,500.00.”

“I have the last round SA rego label which was April 1984. Anton always intended to ride it again so it was kicked over on a regular basis and the motor proved to be near perfect. The engine cases, barrels, heads and carbies and bits and pieces were hydrablasted by Colin Campbell at Rydalmere who did a fantastic job and was very helpful. Brake shoes were resurfaced by Central Coast Brake and Clutch at West Gosford. The frame and tin wear were in great condition for a bike of its age; a little bit of surface rust and thirty years of grime and a few small dings in the guards that had to be rolled out. I had everything sand blasted by Jarvis Sand Blasting at Somersby who was way too cheap for the perfect job he did, then everything was sent away either to Nunawading chrome in Victoria or to the spray painter J and S Spray Painter at West Gosford. The frame was two-packed rather than powder coated as I wanted the effect of minimal colour changes to highlight the chunky motor and chrome the results speak for themselves”.

“The Benelli is almost original except for the Tomasalli head light ears and Laverda-style adjustable handle bars, the paint work and exhaust pipes. All up I spent more than 500 very enjoyable hours on the project and a load of cash, but I have a very understanding wife who is also into bikes and thinks it only cost three thousand dollars and I had to drink copious amounts of beer in the shed to help me sort out the problems.”

Dave’s finished machine is absolutely to stunning to look at, and in my short stint in the saddle, lovely to ride. The pipes emit a throaty burble that is not unlike a British twin, but in reality could not be anything other than Italian. I found the riding position comfortable and the handling crisp, no doubt down to the firm suspension. Sure, the Benelli has its quirks, foibles and a few shortcomings, but as the motorcycling world went four-cylinder crazy in the even crazier ‘seventies, the big twin held its ground and its Latin good looks. The fact that so few reached these shores makes Dave’s bike a real rarity and a guaranteed head-turner wherever it goes.

1971 Benelli 650S Specifications

Engine: Parallel twin OHV

Bore x stroke: 84 x 58 mm = 642.8 cc

Power: 57 hp at 7,400 rpm

Compression ratio: 9.6:1

Carburation: Two 29 mm Dell’Orto VHB

Frame: All-welded stell cradle.

Suspension: Front: Marzocchi telescopic forks. Rear: Ceriani spring/damper units.

Brakes: Front: 230 mm double sided single leading shoe. Rear: 200 mm single leading shoe.

Wheelbase: 1420 mm

Ground clearance: 215 mm

Dry weight: 210 kg

Fuel capacity: 13 litres

Tyres: Front:3.50 x 18, Rear: 4.00 x 18

Top speed: 177 km/h