From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 73 – first published in 2018.

Story: Jim Scaysbrok • Photos: OBA archives, Brendan vandeZand, Nick Shaw, Phil Vergison.

Back in the late ‘seventies, the band Mental As Anything had a big hit with “The Nips are Getting Bigger’, which was about Scotch Whisky, not motorcycles. But with a little imagination, it could have applied to a trend emanating from Nippon itself, specifically Hamamatsu and Tokyo, where first Honda, and later Suzuki and Yamaha, were steadily evolving a new breed of four stroke singles. Singles that did not leak oil, started reasonably easily, and even sounded right. By 1972 these models included the ground-breaking four-valve Honda XL250 and a year later, the rocker-arm breaking XL350, leaving Yamaha with but one choice if it were to steal a march on the opposition – a 500 single.

That single was the TT500C, first displayed at a dealers’ convention in September 1975. Now this was a quantum leap – backwards. Back to the days of the big, bad old British singles, in as much as the TT500 was not a small or mid-sized buzz-box, but a full-on 500 single with internal dimensions that could have come straight from Birmingham. A real thumper. True, the new Yamaha was strictly an off-roader, and in most markets, such as Australia, could not (legally) be registered for road use, although quite a few subsequently managed to get around this. But it was a beauty, make no mistake; a free-spinning engine with heaps of torque, and it was even relatively easy to start, provided you observed the correct rituals. The dry-sump motor carried its lubrication in the top frame tube, freeing up the midriff area that normally belonged to an oil tank for a decent air filter and all the electrics.

It wasn’t long before Yamaha became aware of the need for a second model, with more emphasis on road use and with a battery, lighting (the headlight sourced from the TY250), indicators, instruments, a horn, larger (160mm) front brake, steel (rather than plastic) mudguards, and a street legal exhaust system – all of which added weight but still resulted in a pretty nifty package that sold very well from the moment of its release. The XT engine was basically identical to the TT but used a smaller 32mm carburettor.

So that’s the range, Yamaha concluded, job done. Well, not quite. More than a few XT owners eyed their mount and saw stars – Gold Stars. Herein was the basis for a new breed of road rocket, one that with a bit of work, would not look out of place in the forecourt of the Ace Café. Some attempts were made but the result was always compromised by certain limitations of the donor machine – most notably the overall height and front suspension geometry. It wasn’t just a restyling exercise, and Yamaha was loathe to explore a concept born purely out of nostalgia.

At the time, Sydney advertising agency Harris Robinson and Associates handled the Yamaha advertising account for NSW distributors McCulloch of Australia. There was a great deal of motorcycle experience on tap here, with Vincent Tesoriero in charge of promoting the Mr Motocross Series and previously at the helm of the Castrol Six Hour Race, as well as various staff members who rode bikes. Vincent takes up the story. “We used to travel regularly to Hamamatsu in Japan to have meetings with the Yamaha marketing department. One time around 1976, my business partner Michael Robinson and I went there to be briefed on the various new models and the campaigns they wanted us to develop to launch the bikes into Australia and NZ. One such bike was the brand new XT500, which featured a glorious looking 500cc single motor. Back in Australia we came up with some great creative for the new XT500 model which spoke about the evolution of the 500cc single engine and all the great bikes it had powered throughout the history of motorcycling –Manx Nortons, Matchless, AJS, Gold Star BSA, Velocette and so on. And as the campaign came together it was only natural for us to put two and two together and imagine what the new XT 500 motor would look like in a road frame. After all, both Robbo and I owned 500 Velocettes, so we understood ‘the vibe’.

“A few weeks later when we went back to Japan to present the XT500 campaign, we also had some concept ideas and layouts for a new 500 road bike in my portfolio. These visuals had the concept bike standing proudly alongside the great classic marques and spoke of their racing heritage, successes at the TT Races, and the great riders who rode them.

“At the Yamaha Factory and in front of a room full of marketing people we presented the XT500 campaign and explained the history of the 500 single engine. They seemed to grasp the heritage angle, so we unveiled our idea of using the 500cc motor in a road bike configuration. I don’t know what happened after that. The discussion went from stilted English to animated Japanese and continued for six hours and late into the night. The next morning we were supposed to fly back to Australia, but we were escorted back to Yamaha’s marketing office to repeat the presentation to a room full of development engineers, then again to another group of production people. This went on all day. The room kept filling up with more people, the presentation kept getting slicker and finally the MD comes down and we had to start all over again – for the fifth time. That night we were driven back to the airport without any real idea of what happened or what they thought. Imagine a room of 30 factory people, all dressed in the same uniform, all speaking Japanese, for two days straight. No break. No lunch. We were exhausted and wondering why we had bothered.

“The next morning when we arrived back in Sydney there was a message waiting at the office. Could we go back to Japan at the end of the week with a developed launch campaign on the new Yamaha SR500 model. Could we design a logo for the side cover and what colour should the bike be? The last one was easy…. black with a gold pinstripe.”

“I supplied one of our art directors, Graeme Davey, with a pile of logos from the old British bikes and told him to design a sticker for the side cover that read “500 single”. He came up with a basic idea and John Richards, a finished artist, completed the job. So back we went to Japan, and during the previous week or so, Yamaha had done a lot of thinking as to how to best make it all happen. They had worked out how to use as many existing parts as possible and how the XT frame needed to be adapted, but they were not entirely sold on the heritage aspect and only agreed to produce the stickers for retro-fitting for the Australian market. As it turned out, the new model was an instant success not just here but in England and throughout Europe.

“For the local launch, we assembled a bunch of old British bikes and a group of us from the agency dressed up in period costume. We photographed each bike individually, as well as the SR500, and the artist Alan Puckett, who was a real enthusiast when it came to old bikes and cars, put it all together as a poster. This was used as a double-page spread in magazines, and the poster was supplied in very limited quantities to Yamaha dealers. I still have one hanging in my office.”

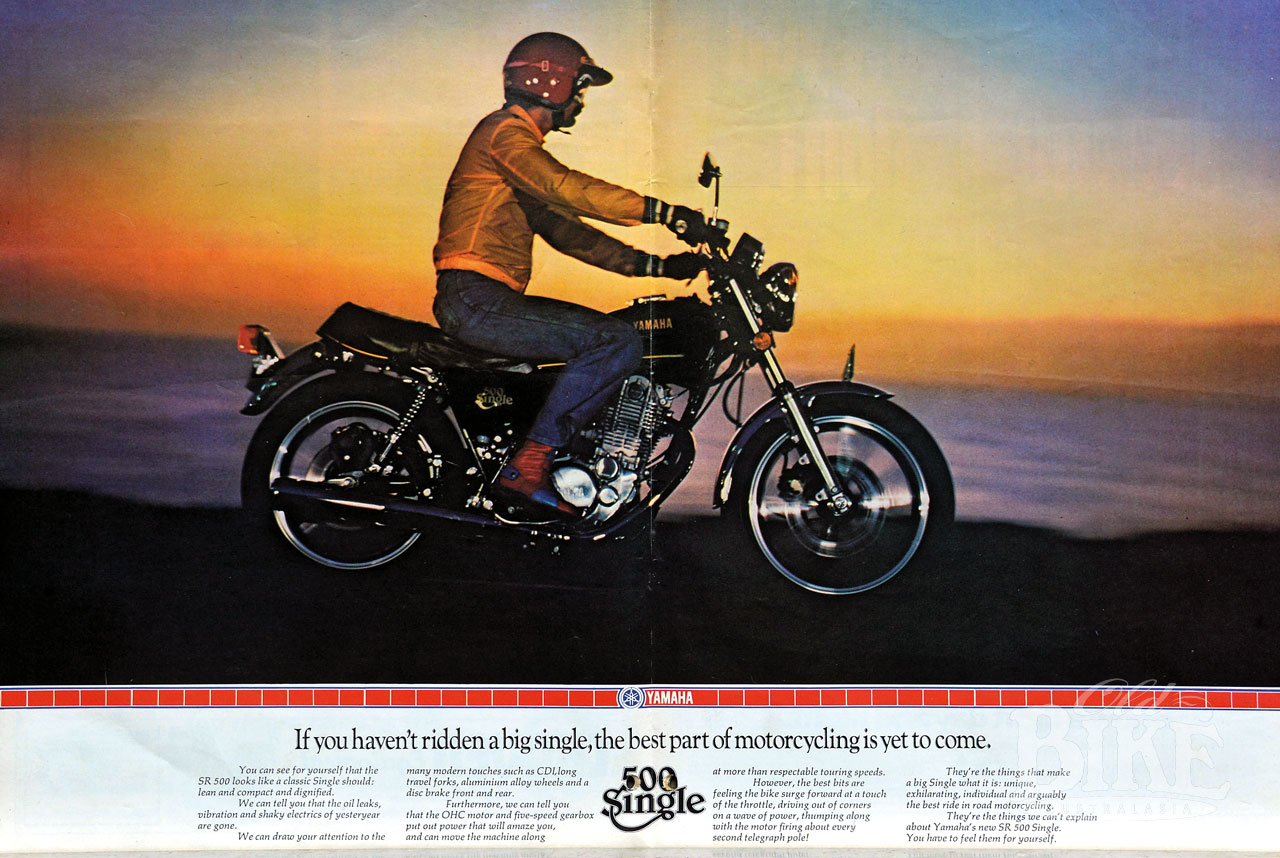

At the time, I was doing freelance work for Harris Robinson & Associates, and there always seemed to be an SR500 or two on loan from McCulloch, which I grabbed at every opportunity. Perhaps my enthusiasm for the model was obvious, because I was recruited as rider in a photo shoot for a series of magazine advertisements. I recall the photographer was obsessed with dawn scenes, which meant 4am starts at various far-flung locations.

Yamaha could not have foreseen just how popular and durable the SR500 was to become, remaining in production from 1978 to 1999. The SR500 retained most of the XT’s infrastructure, the same strong sohc design with its rigid crankshaft supported by large ball bearings, but with a larger inlet valve, modified cam timing, heavier flywheel, and slightly larger finning for the cylinder head. The 34mm carb (with an accelerator pump) was 2mm up on the XT’s, and CDI replaced the XT’s points ignition. Oddly, the internal gear ratios of the SR and XT were identical – odd given that the XT was meant to be a dual purpose/road/trail machine. The frame, with revised dimensions in steering geometry (2 degrees less fork rake, hence 20mm less wheelbase), was of thicker-walled tubing, with extra gusseting around the swinging arm pivot. Instead of spoked wheels, Yamaha opted for cast-alloy jobs which were on the heavy side and contributed to the 23kg weight gain over the XT500. The overall package was still reasonably light, and the new model gained instant and universal praise for its sharp handling and ‘flickability’. Originally for the Japanese market but subsequently sold elsewhere, the 399cc SR400 was identical except for a 67.2mm stroke instead of the 500’s 84mm.

Perhaps the only major grumble was the lack of an electric starter – which Yamaha claimed was for weight-saving – but challenging for a generation of riders who were by now used to thumbing a button to get things under way. Not that the SR500 was a reluctant starter. Yamaha had done much work in this respect and developed what they termed an “automatic decompression system,” which worked, to a degree. The SR500 had a small window at camshaft level on the right side, which provided the would-be rider with a view of a small pointer that came into view at top dead centre. Then it was a case of pulling in the decompression lever on the left handlebar, moving the kick start lever through half its travel, releasing the de-compressor, and letting the lever return to its normal position, whereupon an audible ‘click’ was emitted and it was ready for a full flowing kick, followed, hopefully, by internal combustion.Just don’t open the throttle until the engine is running! For starting a hot engine, the SR has a ‘Warm Start’ button.

In Europe, Australasia and Japan, the SR500 gained cult status in short order. Later models dropped the disc rear brake in favour of a drum, oil capacity was increased, and carburettor size reduced slightly. Around the model, a worldwide industry sprang up supplying café-cool items like alloy tanks, racing style seats, rear-set footrests and foot controls, swept back exhaust systems with megaphone and Gold Star replica silencers, clip-on handlebars, fly screens, plus numerous engine bits.

In Europe, the SR500 was released in 1978 with wire wheels and a drum rear brake, but a year later had adopted the cast wheels with discs, continuing in this form until 1984, when the wire wheels were back, with the front becoming an 18 inch. In 1988 a front drum brake was fitted and this version remained as the standard offering for a decade. For the home fiddler, the SR500 became so popular that today, finding one in original specification is quite rare.

Fast forward

In Australia the SR500 Club is an energetic group of enthusiasts who share a common enthusiasm for the model, and its close cousins – the TT and XT500, SRX600, SZR660 and even the MuZ Skorpion.

The SR500 Club has in its ranks members who have taken the basic machine and created highly individualistic renditions of the 500 single theme; everything from Salt Racers to Flat Track replicas, innumerable café racer concepts, and, yes, even standard originals from the various years. Canberra-based member Stew Ross has cooked up some very tasty versions, and has also produced a comprehensive history of the model; the result of some exhaustive research no doubt. Stew notes, “The SR was styled by Japan’s GK Dynamics and Mr. Atsushi Ishiyama. GK, which is possibly an arm of Yamaha, was also responsible for bikes such as the stylish Yamaha XS 650 twins, the V-Max, and the MT-01, among others. The SR, like the XS1, is a great looking bike with styling that doesn’t really age.”

Stew continues, “In Australia the SR500 was available through dealers for only four model years. The 1978 ‘E’ and 1979 ‘F’ models were released in black/gold with differing pin stripes, and Asahi aluminium mag wheels with single front left and rear right disc brakes with single piston brake callipers. For 1980, the ‘G’ model came in red/gold, and the rear disc wheel had been replaced with one incorporating a rear drum. The 1981 ‘H’ model was basically the same as the G except for the back and red paint scheme. Both G and H models were fitted with a larger 8-inch headlight. Sadly, the 500s were discontinued in 2000.”

It has been pointed out to Stew Ross on more than one occasion that his own initials match that of the model itself, so it is probably not just coincidental that he decided to create another SR – standing for Salt Racer. With his brother Glen, Stew built an SR500 “for a full-on attack on the Dry Lake Racing Association (DLRA) Australian Modified, Partial Streamlining, Fuel 500cc (MPS/F 500cc) 2010 class speed record.” The first attempt was OK, but quickly morphed into a Mk2 version, with full streamlining, which achieved a class record of 125.357 mph.

Despite the demise of the SR500, the SR400 soldiered on with various updates, including new forks, a twin-piston front brake calliper (with the disc on the right hand side), a new style front disc and wire wheels on new hubs. Various internal mods were made in the face of increasing restrictions on exhaust emissions, and in 2008, fuel injection replaced the old CV carb. A catalytic converter now resided in the muffler. Reintroduced to the Australian market in 2014, the current edition of this venerable model, now fuel-injected and selling for a very reasonable $8099, the SR400 introduces the joys of kick starting to a new generation of learner riders. Moreover, it provides a palette for individual expression like few other current motorcycles, and a riding experience virtually unique in this day and age. It came from good stock and was, in no small part, conceived right here back in 1976.

Thanks to several members of the SR500 Club, including Craig Lemon, Stew Ross, Mike Cowie and Brendan vandeZand for their assistance with this article.

Specifications: 1978 Yamaha SR500E

Engine: Air-cooled 4-stroke single, sohc.

Bore x stroke: 87mm x 84mm 499cc

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Power: 33hp at 6,500 rpm

Torque: 38.2 Nm at 5,500 rpm

Lubrication: Dry sump, trochoid pump.

Carburation: Mikuni VM34SS

Ignition: CDI

Staring: Kick

Frame: Tubular steel, single downtube, semi double cradle.

Suspension: Front: Telescopic forks, two-way damping 150mm travel. Fork rake 27.5 degrees, trail 117mm. Rear: Kayaba oil-damped shocks.

Wheels: Cast alloy wheels with single discs and single-piston floating callipers.

Tyres: Front 3.50 x 19, Rear 4.00 x 18

Fuel capacity: 12 litres

Dry weight: 163 kg

Wheelbase: 1410mm

Maximum speed: 151 km/h

Price: (NSW 1978) $1,775.00