From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 91 – first published in 2020.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Troy Creighton, Jim and Sue Scaysbrook

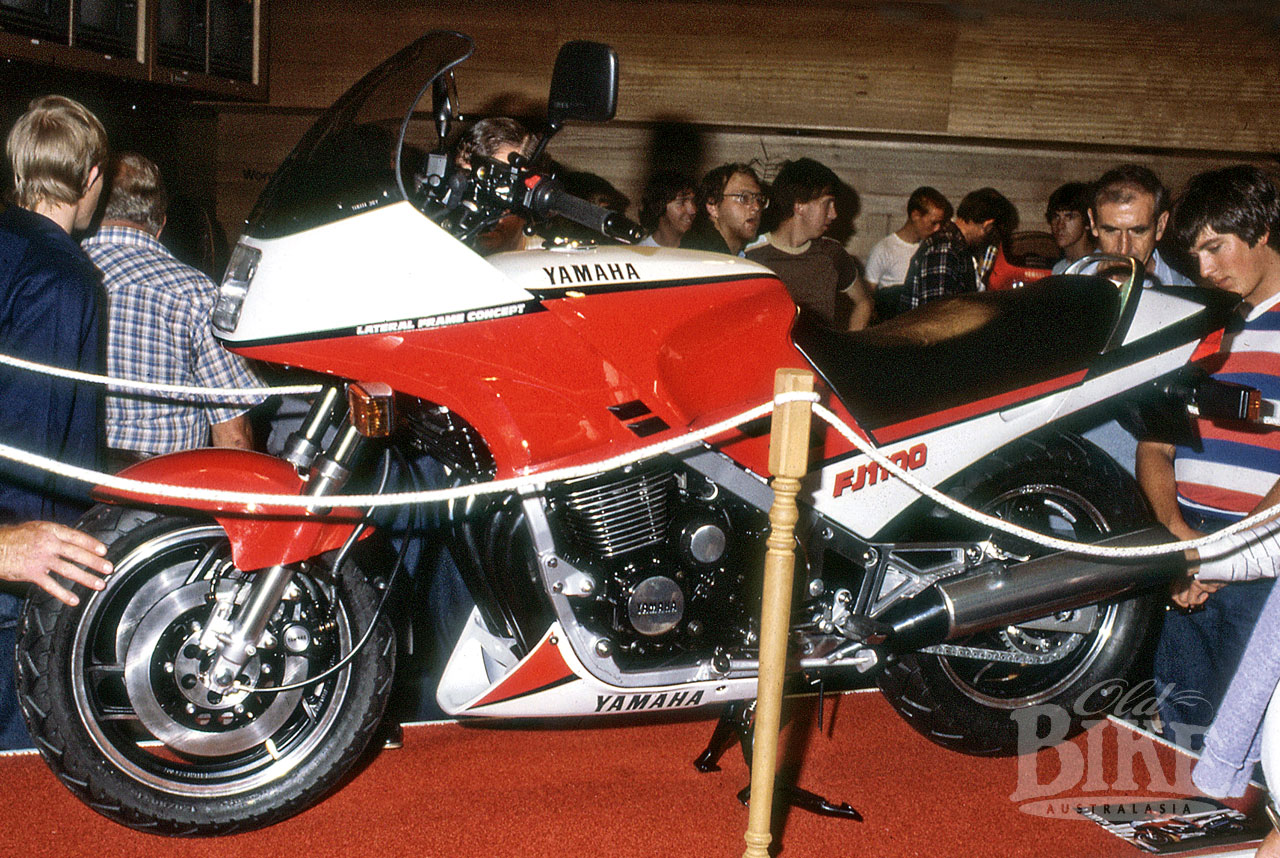

When it was released in 1984, the Yamaha FJ1100 probably created the category now known as Sports Touring. It was big, comfortable, and heavy, but it handled amazingly well and durable in the extreme.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw an FJ. It was 1984 and William Street, Sydney – the big hill up to the famous Coca Cola sign at Kings Cross. This squat, red and white thing just surged past, zoomed up the rise and disappeared. “What the…?” Investigation was required, especially as I was beginning to get itchy feet with my current road bike, the second of two Honda CB900F models that I owned. The Honda was fast –very fast – handled well, and was comfortable, but…it was time for a change.

A test ride, a trade-in deal struck, and into the garage went Big Red. The thing that impressed me instantly on the test was the plush, luxurious seat – a far cry from the usual offerings. At just 780mm the seat height was low enough to accommodate virtually any rider, and was another ace in Yamaha’s aim to lower the overall centre of gravity as much as possible. The footrests were positioned quite rearward, and not mounted in the usual spot on the lower frame tubes, but near the swinging arm pivot. With the seat also mounted towards the rear, the relationship between footrests, seat and the clip-up style forged aluminium handlebars was perfect for me.

In fact, I loved everything about the FJ; the styling, the grunt, the handling, the comfort and the practical touches that abounded. These included the easy-release seat with quite a bit of space inside the cowling behind the very comfy seat. The self-cancelling turn indicators were a marvellous innovation – I have always thought that these should be a mandatory safety feature on motorcycles, and anyone who has failed to turn off a ‘blinker’ and suffered the consequences of having a car pull out in front of them would have to agree.

This was a well-thought out bike that was a winner straight off the drawing board. At that stage, I was changing bikes every couple of years, but the FJ1100 remained with me for a decade, during which time it clocked up a fairly modest 100,000 kilometres. And apart from tyres and a rear chain, oil and filters, I spent nothing on it. Even when it was time to part, the FJ1100 was replaced by an XJR1200 – basically the same thing but with a conventional frame.

A look around

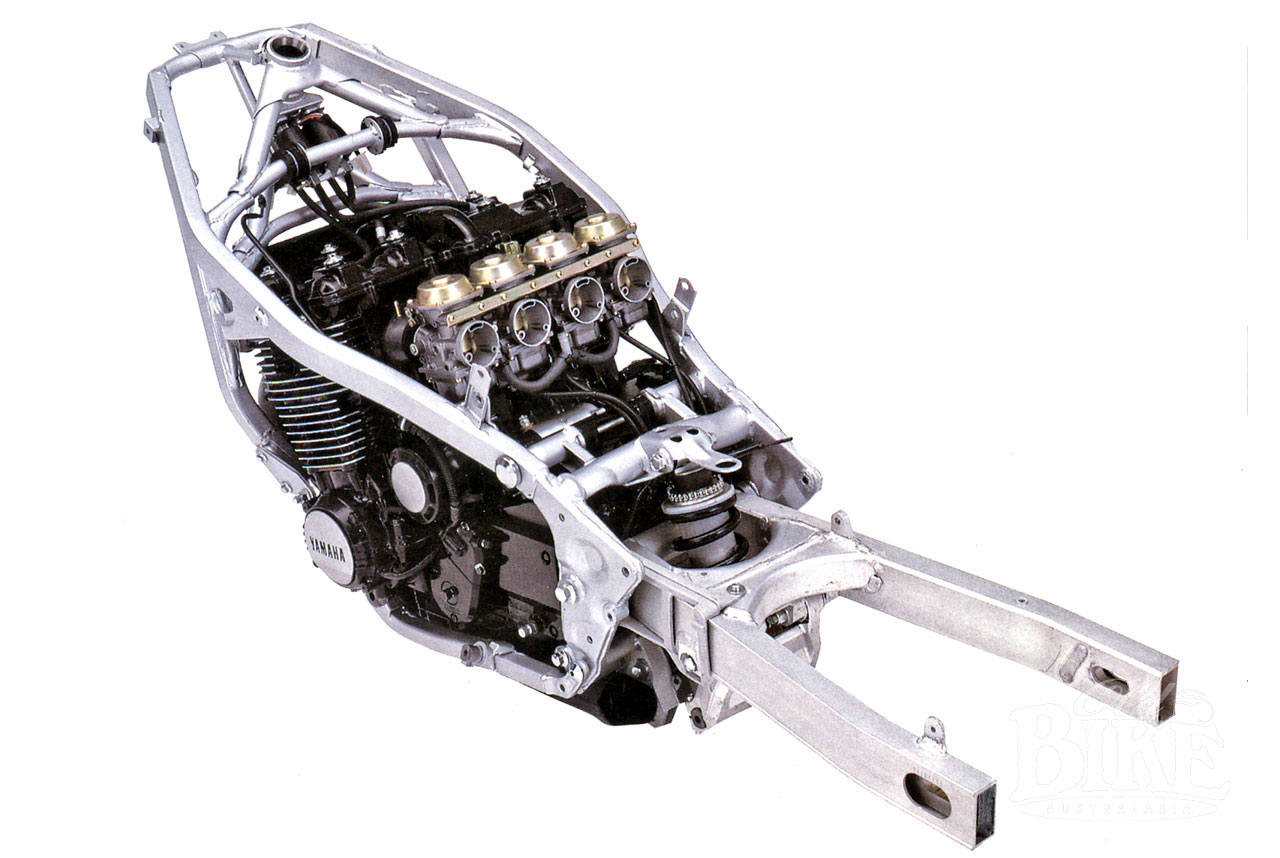

Speaking of frames, it was this item that really set the original model apart from its contemporaries. Yamaha called it their Lateral Frame Concept, and what this meant was that the conventional steering head was surrounded by a loop extension of the main frame side members, with additional bracing to provide a flex-free structure. The top and bottom steering yokes and the fork tubes themselves in effect rotated inside the frame structure, which was made from box-section high tensile steel tubing. The rear engine mount and the swinging arm pivot were in a fabricated section covered by an alloy plate. Very neat. Very strong. Bottom frame rails were detachable to ease removal and installation of the engine unit, and the rear sub-frame was also a bolt-on structure. With the main frame top tubes so widely spaced, access to the cylinder head and carburettors was much simpler. The square section tubing forward of the steering ahead also provided a secure platform from which to mount the half-fairing and the large and colourful instrument cluster.

The forks were reasonably conventional, with 41mm stanchions with a cast-alloy cross brace to reduce side flex. An hydraulic anti-dive system was built into each slider, with spring pre-load and damping for both legs adjusted by a single control. At the rear sat a vertically-mounted singe shock absorber with a rising-rate linkage, with five-way spring pre-load and damping adjustments via a remote control dial that operated a chain drive to the unit itself. The swinging arm was in generously proportioned rectangular sectioned alloy tubing.

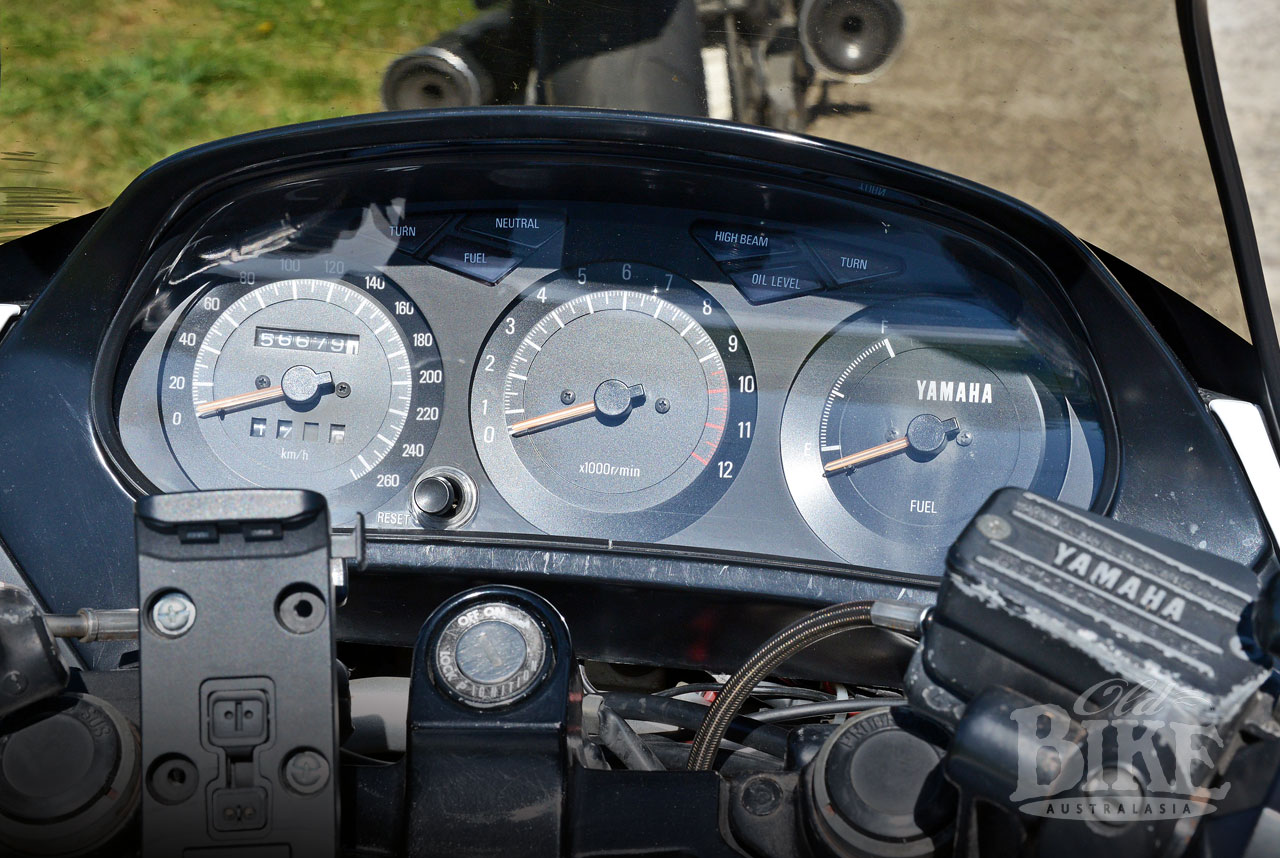

A further example of the somewhat avant garde nature of the design was the use of 16-inch cast alloy wheels front and rear, fitted with fat V-rated tyres. There was no suggestion that the new model was intended for track work, but the scarcity of suitable 16 inch rear tyres took care of any notions in that regard anyway. This was an urban tourer through and through, with a very sensible 24.5 litre fuel tank with a flat top to permit easy mounting of a tank bag. The fuel tap was pressure-operated, negating the need to switch it on and off, with no reserve setting. Instead, a low-fuel warning light was incorporated in the instrument panel. The fairing, extending only to the level of the cylinder head on each side, was necessarily wide to fit around the frame, with a tinted screen above. Downstairs, partially encasing the lower exhaust pipes and central collection box from which the two rear pipes and cylindrical mufflers exited, sat a ‘belly cowling’ which may not have had any practical purpose, but it certainly looked right and balanced the top fairing nicely.

Yamaha must have been tempted to go the whole hog and fit a shaft drive to the FJ (as it did with the XS11), but opted to stay with the latest in O-ring chains, which had admittedly come a long way in recent years. Yamaha’s excellent opposed-piston brakes, versions of which had adorned many models (including the racing TZs) over the years, continued to prove entirely adequate, working on twin ventilated steel discs at the front and a single disc at the rear.

And let’s not forget the power plant – a new design that admittedly owed quite a bit to the XJ series. Great effort had been placed on making the unit as narrow as possible, and as light as possible. The cylinder head featured double overhead camshafts with four valves per cylinder, valve clearance adjustment by shims, dual pumps to circulate oil through the engine and oil-cooling radiator, with the latest thinking in combustion chamber and piston head design to cope as much with combustion efficiency (and emission outputs) as outright performance. In the basement sat a one-piece crankshaft turning in plain bearings. A unique feature (at least to Yamaha) was the large diameter holes set into the crank webs, enabling air in the crankcase to pass between adjoining cylinders to reduce power losses. The small Nippondenso transistorised electronic ignition was located on the left end of the crankshaft and using a vacuum-controlled advance system, with the chain-driven 364-watt alternator, with a built-in voltage regulator and rectifier, sited below the carburettors and above the gearbox, contributed to the minimal overall width of the unit – a design that Yamaha pioneered and was seen on Suzukis within a year of the FJ’s release. There were five ratios in the gearbox, with a hydraulically-operated diaphragm spring clutch. The straight-cut primary drive gear was cut into the number three cylinder, eliminating the need for a separate gear. In reality, there was nothing particularly radical about the engine, which is probably why the FJ gained such a reputation for reliability and robustness.

Sedate touring may have been the FJ’s raison d’etre, but it sure was fast. Yamaha claimed 235 km/h (146 mph) but this was no overstatement – one magazine achieved exactly this figure on a stretch of desert road in California. Cycle World magazine also took one to the quarter mile drag strip at Carlsbad Raceway and reeled off a 10.87 pass – the quickest time ever posted in one of their numerous road bike tests. Yamaha spent a long time- almost four years – developing the FJ though various versions before deciding on the final specification. Even a six-cylinder version was reputedly contemplated.

Moving right along

The FJ1100 gained instant acceptance and sold well in most major markets, which is why I was surprised that, in less than two years, an upgraded model with a 1200cc engine was in the showrooms. This was officially known as the 1TX version, and was followed by the 3CV and finally 3XW. The increase in capacity (from 1097cc to 1188cc) was achieved by enlarging the cylinder bore from 74.0mm to 77.0mm, while retaining the 63.8mm stroke, and gave around seven extra horsepower. Compression ratio also went up marginally from 9.5:1 to 9.7:1. Initially, the main difference was a slight increase in peak power and a more useful increase in mid-range torque. The rear shock was redesigned to provide a greater range of adjustment, the front forks lost the anti-dive mechanism (which had generally fallen out of style within the industry in favour of more sophisticated internal damping control), and for some reason, 2.5 litres disappeared from the fuel tank capacity.

There was also a 14 kg hike in weight, some of this due to the incessant need to keep abreast of emissions via more restrictive (and heavier) exhaust systems and engine breathing. On the 1200, the fairing grew a little wider and the screen taller, and the wheelbase slightly longer in the interests of extra stability at high speeds. Successive models sported subtle refinements but the basic package remained. A 17 inch front wheel appeared in 1987, and brakes were uprated the following year, with four-piston front and twin-piston rear calipers sourced from the FZR1000. 1988 also saw the introduction of a fuel pump to the carburettors instead of gravity feed.

The 1991 FJ1200A was the first Japanese motorcycle to employ ABS, with separate braking circuits front and rear linked to a central ABS hydraulic unit housed in the rear bodywork. ABS continued as standard fitment until the FJ1200 was finally laid to rest in 1996, three years after sales were curtailed in USA and some other markets. By this point large capacity motorcycles were increasingly liquid-cooled with fuel injection rapidly taking over from carburettors. Over the 13 years of production, colour options changed, although the original and distinctive red/white or red/silver is the colour scheme most generally associated with the model. It is believed around 64,000 FJ1100s were built in 1984-1986, with a further 300,000 of the various FJ1200 models over the subsequent decade. The final models were actually assembled from parts stock and delivered in 1995 and early 1996.

A keeper, for most

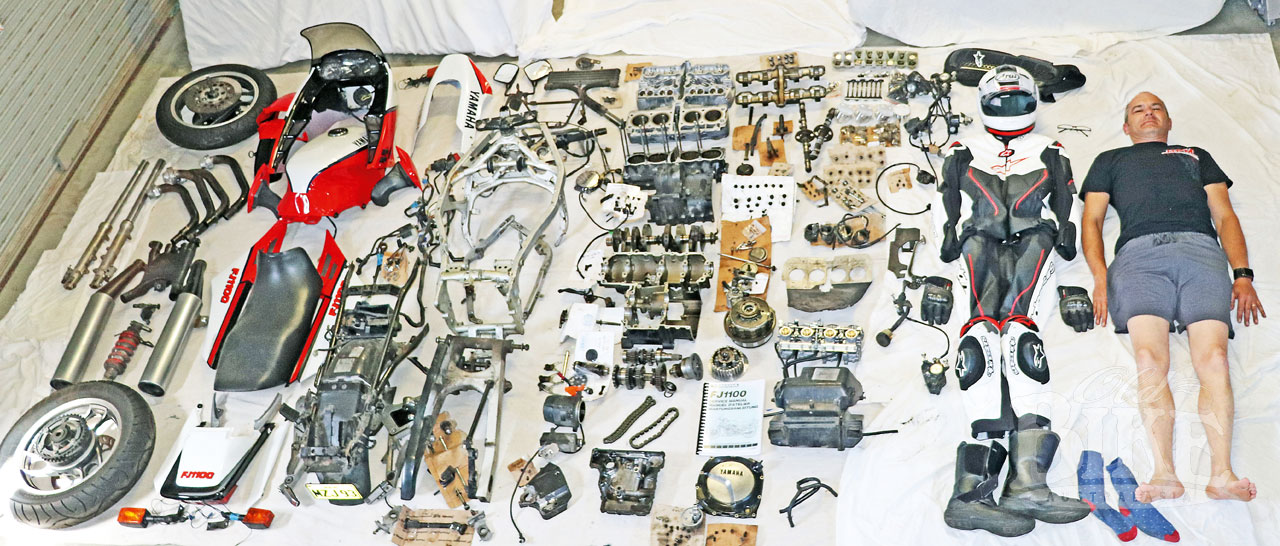

Almost 25 years after it was last produced, the Yamaha FJ1100/1200 has a cult following world wide. The most common description amongst the legion of owners and admirers is “bulletproof”, which adequately describes most of the motorcycle. Of course, there are minor items that crumble under the ravages of time, notably the original silencers, clad in a special grade of steel that is 76% nickel and 11.5% iron, and that are today all-but unobtainable, the belly pan, which develops lumps and bubbles, and becomes brittle due to its proximity to the exhaust pipes (and to being bashed over gutters and kerbs), and minor plastic components. Some of these parts are being reproduced in small numbers. But by and large, this is a motorcycle for the ages, and it has one big advantage for the neo-classic enthusiast in that it is relatively simple to maintain or rebuild. The air-cooled engine is straightforward in concept and execution, the chassis extremely robust, suspension still quite adequate, and even the favoured cross ply tyres are available if you look hard enough. There are numerous owners groups that keep members informed of tweaks, parts availability and workshop knowhow.

Unfortunately for would-be restorers, many FJ1200s have been sacrificed to build race bikes (and small racing cars such as the Aussie Legends class) for various retro categories around the world, including the Legends class in USA, British classic classes and one-offs like the Phillip Island Classic here in Australia. The narrow engine is a big plus for racing, and with modern internal mods, tuners get around 160 horsepower out of the engines, albeit with fragility. Mounted in modern frames from Harris and others, with uprated suspension and brakes, these bikes are capable of lap times not that far from top Superbikes.

Joining the party

FJ Owners Groups are everywhere: Germany, Spain, Italy, France, Canada, Croatia, South Africa, Holland, Norway, USA, New Zealand and, of course Australia, sharing camaraderie, tips and advice, social outings and more. One such get together happened in September 2020 when owners located mainly on the South Coast of NSW took advantage of relaxed COVID restrictions to head out for a couple of days on a ride coordinated by Pete Hoare. We caught up with them at a lunch stop at Robertson in the NSW Southern Highlands; a location that is more often than not bursting with motorcycles. Around a dozen examples were already assembled outside one of the local bakeries when we arrived, with several others arriving soon after.

A rusted-on FJ man

Lyndon Adams from up Newcastle way is a very keen FJ fan – he has owned six all up, including one that was stolen for what he considers was “an order for a 1200 engine to put into a racing car”. He has a shed housing FJs of various vintages and degrees of originality. The loss of that one encouraged him to buy another of similar vintage – a 1991 model built in 1990. This one is his constant ride and is fitted with a US-made RPM rear shock and RPM forks springs and Emulator valves.

Specifications: 1984 Yamaha FJ1100

Engine: 4 cylinder DOHC, 16 valves, air cooled.

Capacity: 1097cc

Bore x stroke: 74.0mm x 63.8mm

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Max Power: 91.9 kW (123.2 hp) at 9,000 rpm

Max Torque: 103 Nm at 8,000 rpm

Lubrication: Wet sump

Carburation: 4 x Mikuni BS36

Ignition: Transistor electronic

Fuel tank capacity: 24.5 litres

Transmission: 5 speed, chain final drive

Wheelbase: 1490mm

Seart height: 780mm

Dry weight: 227kg

Suspension: Front: Telescopic forks with anti-dive, 3-way per-load, 3-way damping adjustment. 126mm travel.

Rear: Yamaha Monocross, 17-way rebound damping and 12-way spring preload adjustment. 120mm travel.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 282mm discs, twin piston calipers

Rear: 1 x 282mm disc, twin piston caliper.

Tyres: Front: 120/80 V-16 Rear: 150/80 V-16.

Top speed: 235 km/h