The Vincent Black Lightning is perhaps the most revered motorcycle in the world. Just a handful exist, and this one still carries the grime from countless battles under its mudguards. 5,000 miles on the clock, and every one of them in anger.

Black Lightning. Even the name sounds very fast, particularly coming from an era of pedestrian British fare with model names like Plover, Huntsman and Flying Fox. And fast it was – capable of exceeding 140 mph without raising a sweat.

Right from the time of the release of the post-war Series B twin in Rapide form, the Vincent HRD was the king of the horsepower race for production motorcycles, but almost immediately, owners wanted more and more horsepower as the big twin was pressed into racing service. Naturally the Rapide was sought after as the king of the road burners, for those who could afford one, but out here in the colonies it was even more keenly eyed as a competition mount, particularly for sidecar racing, where the upper capacity limit was usually unlimited. Geelong’s prolific racer and motorcycle dealer Frank Pratt secured the first Rapide to come to Australia, and immediately began to clean up in local competition. London dealer Jack Surtees (father of future world champion John) had been racing a Norton outfit with some success, and order a Rapide with some special tweaks, this engine being built at the factory alongside a second ‘hottie’ which was loaned to factory Experimental Tester George Brown. Brown gave the machine its competition debut at Cadwell Park, Lincolnshire, at Easter 1947. For the prestigious Hutchinson 100 at Dunholme airfield later in the year, Brown’s special Rapide was further breather upon, including having a special petrol tank (to hold the abysmal 72-octane fuel of the day) made – a standard Rapide tank with an extra section grafted on to allow the 100 mile race to be completed non-stop. He finished second to Ted Friend’s works 500 cc AJS Porcupine, but unlike the AJS, the Rapide, re-fitted with silencers, was ridden back to the factory after the race. In this form, it was extensively tested soon after by respected journalist Charles Markham of Motor Cycling magazine. Markham was ecstatic in his praise for the special Rapide, stealing a phrase from Rudyard Kipling’s poem Gunga Din, in which a British military officer’s life was saved by a lowly water bearer, prompting the lucky fellow to remark, “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din”. Markham’s inference was that the motorcycle’s capabilities far exceed his own, but the sobriquet stuck, and henceforth Brown’s increasingly successful mount became known as Gunga Din. The special used polished 65-ton conrods, E7/7 pistons giving 7.3:1 compression ratio, polished rockers and 1.125” carburettors. The specification largely passed to the new Black Shadow – the uprated Rapide that famously featured (and needed) a speedo specially built by Smith’s instruments to record 150 mph instead of the standard 120 mph item. The engine of the new model, at first produced in very limited numbers, was stove-enamelled black. To assist in publicity, Gunga Din also had its engine pained black, and Brown continued to race the machine with considerable success in Britain.

In mid-1948, a pair of Rapides that had failed to pass their final inspection because of rattly engines were loaned to Brown and fellow racer Phil Heath for use in the 1948 Isle of Man Clubmen’s TT. Brown controlled the race until he ran out of fuel on the last lap, leaving another Rapide ridden by J.D. Daniels to win from Heath.

At about this time, Phillip Vincent had agreed to sell a specially-prepared Black Shadow to wealthy American enthusiast John Edgar – the machine to be ridden by Rollie Free at Bonneville Salt Flats in an attempt on the American Speed record, which at that stage was held by Harley-Davidson. Crucial to its performance (and much increased price tag) were the so-called Mk2 cams designed by Irving. To make the scheduled date for the attempt in September 1948, much midnight oil was burnt at the factory to produce the necessary ‘go-faster’ bits, and Edgar’s engine run-in on the test-bed before being installed in a Black Shadow chassis and tested at Gransden airfield. With Brown aboard, it ran happily to 143 mph and would have gone faster had the runway been longer. In Utah, Free, famously clothes in just a pair of swimming trunks, succeeded in smashing the US record, leaving it at 150.3 over the measured mile. Ironically, Free’s success also helped to seal the fate of the old H.R.D. (Howard R. Davies) brand. To avoid confusion (in the US) with Harley-Davidson, which was usually abbreviated to HD, the motorcycles became known as Vincents, although for some time HRD was still displayed on the crankcases due to the stockpile of parts.

The idea of producing a special racing model was perhaps a natural progression once the Black Shadow had evolved from the Rapide. In what was a very big year for Vincent HRD, the Earl’s Court Show, which had disappeared in 1938, was rescheduled and received enormous support from the British and European manufacturers. Vincent chose to launch its new Series C models with the company’s own Girdraulic forks and hydraulic rear damper, the new single cylinder Comet, and the exciting Black Lightning. Details of the latter were kept secret until just before the show in November, mainly due to the fact that the machine had yet to be built!

The Lightning caused a sensation at the show, despite its whopping £400 (plus the home tax of £108) price tag. From this point on, we are into the mystic subject of just how many genuine Black Lightnings were produced, where and to whom they were sold, what happened to them, and where the survivors are now. Arguments rage interminably, and there is no doubt that the real figures have been polluted with replicas and rebirths, complicated by the use of Lightning engines in racing cars, false number stamping, and the appetite for engines in speedway and road racing outfits. Nothing polarises opinion amongst Vincent buffs like the Lightning numbers, but it is generally thought that 30 complete machines were built, plus several engines. The first two ‘Lightningised’ engines for Surtees, and Brown’s ‘Gunga Din’ were numbered F10AB/1A/70 and F10AB/1A/71 respectively, and the special Shadow sold to John Edgar in July 1948 was F10AB/1B/900. Subsequent Lightning’s all carried the ‘IC’ middle number, and the third of these to leave the factory, F10AB/IC/1803, was sent to Sydney in March 1949 and purchased by champion sidecar racer Les Warton. In the four years 1949-1952 beginning with Warton’s machine, which varied from what was to become accepted Lightning specification by having standard pressed steel brake drums and HRD crankcases, six complete bikes plus one engine came to Australia. These were sold via agents such as Sven Kallin in Adelaide or Jack Carruthers in Sydney, and two more were privately imported, one such being South Australian Gordon Benny’s bike, which he found in Singapore. John Penn’s proposed record breaker was privately imported but carried no engine number.

But let’s go back to Gunga Din briefly, via the exploits of the flamboyant Tony McAlpine. At 14 and a half stone, Tony was a big boy, and well suited to a big machine like a Vincent HRD. Prior to the war, a teenage Tony had made a huge impression on the dirt Miniature TT tracks of Sydney such as Whynstanes, where he flung his BSA around in an inimitable style that had little in common with the neat figures cut by the stars like Eric McPherson and Harry Hinton. Post-war, he was back on the dirt tracks and dabbling in road racing, but it was the purchase of a new Vincent HRD in 1949 that catapulted him into the top echelon. Tony and the HRD were virtually unbeatable in Unlimited class events. He won 12 major races from 13 starts, and it would have been a perfect score had the rear sprocket bolts not sheared when he had the 1950 Bathurst TT in the bag.

For the 1951 European season, Tony decided to try his hand overseas. He secured a 7R AJS for the Junior class and a Gilera Saturno for the Senior, and performed well at the Isle of Man TT, finishing 13th and the Junior at 83 mph. In between races, Tony worked at the Vincent factory at Stevenage, and with the factory’s blessing, assembled his own Black Lightning, engine number F10AB/1C/7305, frame number RC9205. His very last appearance in Britain in 1951 was at Boreham Aerodrome, a very fast circuit, in a programme which included an Unlimited race – usual in Britain where the traditional Senior (500cc) was normally the main class. For the meeting, Phillip Vincent invited Tony to ride Gunga Din, and he did so with all his old verve, sliding through the corners and demolishing a field that contained riders of the calibre of Geoff Duke on a factory Norton. His mission, and his aim of competing in the TT, accomplished, McAlpine sailed for home, taking with him the unloved Gilera (which had broken valve springs almost every time he rode it) and the new, un-raced Black Lightning. He had intended to take up where he left off and had no plans to return to Europe, but after receiving a generous sponsorship offer from Shell, plus the nomination as Australian representative for the TT, he decided to return for 1952. To save money and make sure he was uninjured he did not race during his brief return to Australia, and put both machines up for sale.

The price asked for the Lightning – around $1100 – would have bought a couple of nice houses in Sydney at the time, and buyers were scarce. The Unlimited class was also out of favour with the increased availability to Senior class bikes, and the machine was still unused as the traditional build-up to the Easter Bathurst meeting began. One of the few riders with sufficient wherewithal to own the Lightning was car dealer Jack Forrest, a talented rider who had come up through the Miniature TT scene and had always had competitive machinery. At the 1951 Australian TT held at Lowood in Queensland in June, Forrest was the star of the show, taking out the Junior on a KTT Velocette and the Senior on a Manx Norton. He had a third mount for the meeting, a Vincent Black Shadow on which to contest the Unlimited class, and he was out in front in that race too before a split fuel line sprayed methanol over the rear tyre. Although he controlled the resulting skid, his race was over. Still, Forrest had seen that a well-tuned Vincent on a fast circuit was still superior to even the best Norton, so when the opportunity to acquire McAlpine’s Lightning came along, it proved irresistible. He took possession of the bike in time for the first meeting held at Mount Druitt using both the wartime airstrip and a gravel sealed loop road which constituted what was called at the time, the ‘Mountain’ circuit, as previous racing at Mount Druitt had been limited to blasts up and down the air strip, and around oil drums at each end. In practice, Forrest set a sizzling pace, but last less than a lap in the race when the big twin oiled a spark plug. It was enough however for maestro Hinton to declare that Forrest and the Lightning would be unbeatable at Bathurst one month later. And so it seemed. Again in practice, Forrest was spectacularly quick, reportedly topping 140 mph on Conrod Straight. In the programme-ending Senior (Unlimited) TT Hinton made a slick getaway from the push start and led over the mountain on the first lap, only to have Forrest blast by as if he were standing still on the first run down Conrod Straight. Across the line to complete the first lap, Forrest had the front wheel pawing the air, and rocketed up Mountain Straight with Hinton trailing in his wake. But a few hundred metres later, at Quarry bend, it all went wrong, and Forrest and the Lightning clouted the fence, without serious injury and with mainly superficial damage to the bike. The experience seemed to break the love affair with the Vincent, for Forrest began moves to acquire a new Manx Norton and placed the Lightning with Sydney dealers Burling and Simmons in their Auburn showroom. There it sat for some months, with no takers save for young Jack Ehret, who had a motorcycles shop himself at Randwick and Mascot. He had Vincent experience too, and had actually won the race at Mount Druitt (riding Harold Braun’s Rapide) where Forrest had oiled the plug. With a fledgling business consisting of two motorcycle shops to run, Ehret was not exactly flush with funds, but was driven by the fear that if he did not get hold of the Lightning, one of his racing rivals would. And so F10AB/1C/7305 found a new home, and would remain there for the next 47 years.

Ehret’s experience as a speedway rider stood him in good stead when it came to controlling the Lightning, and he raced as often as he could afford to, interstate as well as in NSW. His first major outing was at the Australian TT at the Little River road circuit west of Melbourne on Boxing Day, 1952 where he finished a fine second to Maurie Quincey’s new ‘Featherbed’ Manx Norton in the Senior TT. At the time, the Australian Land Speed record was constantly under attack, usually from Vincent riders. In January 1953, Ehret selected a remote stretch of road between Gunnedah and Tamworth in western NSW on which to challenge Les Warton’s record of 122.6 mph. Despite constant problems which included breaking the gear lever on the first run (where he recorded 149.6 mph) and having a broken oil ring in the rear cylinder, he averaged 141.509 mph to smash the record. Jack said the attempt had cost him in excess of £1,000 but he considered it was well worth it to claim the coveted piece of paper from the Auto Cycle Council of Australia. On his way back to Sydney he was booked for travelling at 38 mph in a 30 zone! His crown as Australia’s fastest man was short-held however, as four months later West Australian Harry Gibson, also Vincent mounted, raised the record to 144.9 mph, then in December the same year, Col Crothers took his Vincent to Narrabri, NSW and set not just a new motorcycle record, but the fastest time for a car or bike at 146.4 mph.

Over the next five years, Jack and the Lightning were regular fixtures at road race meetings, with the Vincent appearing in both solo and sidecar form, with Stan Blundell in the chair. Undoubtedly its proudest moment as a solo came at the much-vaunted ‘International’ meeting at Mount Druitt in February 1955, where Geoff Duke, the World 500 cc Champion was the star attraction with his works 4-cylinder Gilera. Duke had demolished the opposition in his previous starts on his Australian tour, but on his home track, Jack Ehret was fired up for action and fancied his chances in the Unlimited TT. Reporting on his tour in the English motorcycle press, Duke had this to say. “ Ehret made a poor (push) start in the Unlimited event, whereas I was first away, and piled on the coals from the beginning. Thereafter I was able to keep an eye on the Vincent rider approaching the hairpin as I accelerated away from it. Although he was unable to make up for his bad start, Ehret rode to such purpose that he equalled my fastest lap, and we now share the honour of being the lap record holders (at 1 minute 43.2 seconds).” After this scintillating performance, Jack bolted on the chair and won the sidecar race!

There were low points too, such as the massive crash at Mount Druitt in October 1954. Ehret was leading the Unlimited TT when he entered the corner onto the top straight too fast and fell heavily, the Lightning, somersaulting down the track before it was struck by Keith Conley’s Matchless G45 which had been right on Jack’s hammer when he threw it away. With both riders lying unconscious on the track, third place man Bob Brown stopped to render assistance until officials arrived. Both Jack and Keith recovered with little more than bruises and concussion, but both the Vincent and the G45 were considerably worse for wear.

One result that had eluded Jack so far was the premier Bathurst TT, but he put that right at Easter 1956. From the start of the Sidecar TT Jack and passenger George Donkin bolted away to a clear win over the Vincents of Col Cheffins and Keith Johnston, in a race which saw several serious accidents, including a fatality to Bob Jarvis. Perhaps with this goal achieved, Jack and the Vincent became less frequent competitors, and when Mount Druitt closed in 1958 the machine was mothballed for ten years. In 1968 he made a comeback of sorts at Oran Park, with the Lightning now fitted with 16-inch wheels and John ‘Tex’ Coleman in the sidecar. Despite the long layoff, Jack did not disgrace himself, flinging the machine around and finishing a fighting third in the Sidecar Feature. It proved to be a one-off and a further decade passed before he trotted the Lightning out for one more gallop, again at Oran Park. By this time, the Vincent was in a different class – Historic – and Jack showed all his old fire to demolish the field to win both his races by almost a complete lap. Its last appearance was at the then-new eastern Creek circuit in 1992 where it won the Historic Sidecar race ridden by Jack’s son John Ehret. Thereafter, the Lightning went into a long hibernation in a shed in Sydney as Jack began a different life running a nightclub in Asia. The old warrior languished quietly, with a few other Vincents for company, until it was put up for sale in 1999.

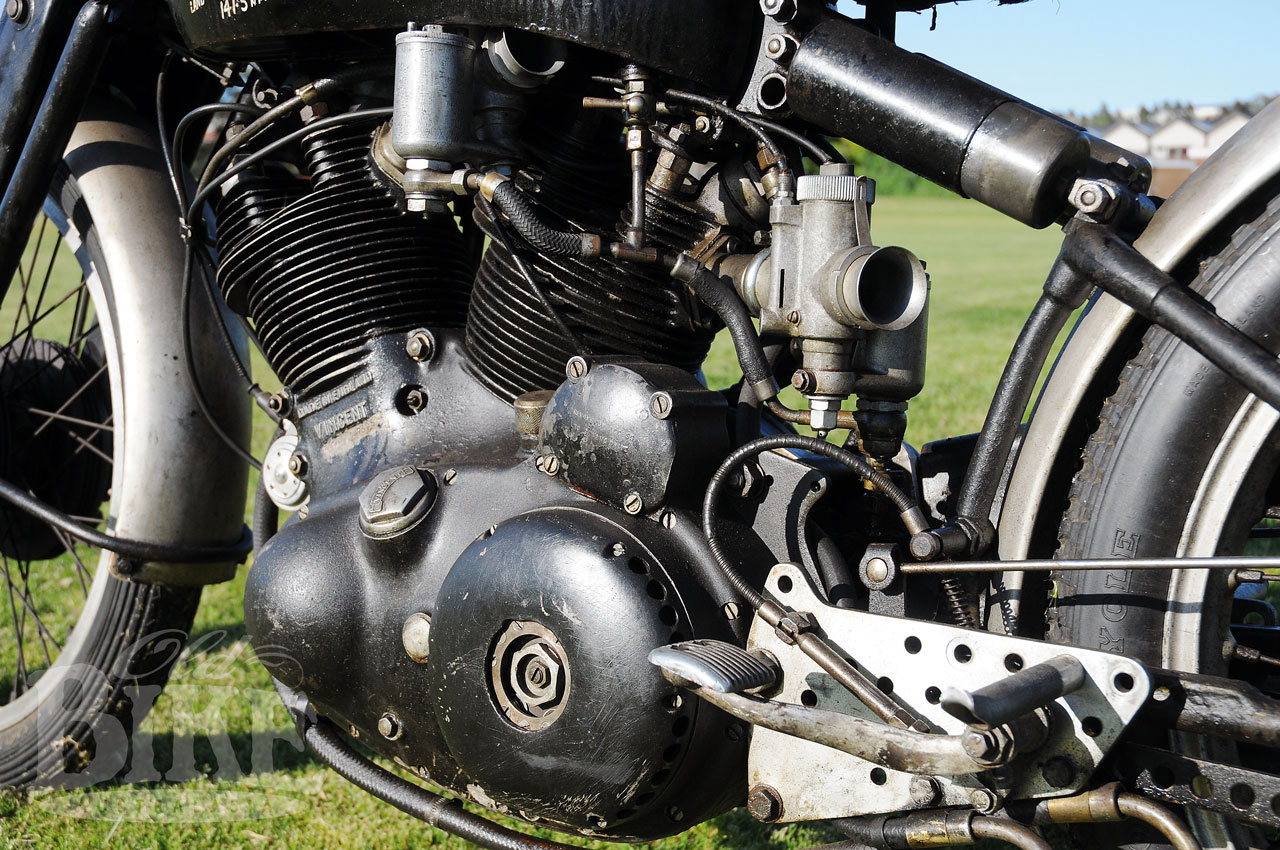

The new owner was Franc Trento, owner of Melbourne-based Eurobrit Motorbikes, and a noted Vincent fancier. Franc determined immediately that the Lightning would not be restored and retired to a museum, but would be kept in exactly the condition he acquired it, complete with ‘1955 dirt under the mudguards’. It had been returned to its original specification with 21-inch front and 20-inch rear wheels, the front being a very rare ‘big-fin’ drum, and both shod with period Avon Racing tyres. The only non-original part was the seat, which had been modified extensively over the years and finally disappeared. Franc was able to obtain a replacement from the USA at an ‘astronomical’ cost, but the machine simply would not have looked right without it. Far from becoming a static piece, the Lightning has been trotted out to many events including having a blast up the runway at the 2007 Vincent International Rally at Ballarat and taking to the track at the Honda Broadford Bike Bonanza at Easter 2009 and 2010.

In its 59 year existence, Vincent Black Lightning engine number F10/AB/1C/7305, frame number RC 9205 has clocked up 8,587 kilometres (the kilometre speedo fitted from new in ‘European’ specification) and virtually every single metre has been covered in pursuit of glory. And as far as Franc Trento is concerned, 7305 is not ready for the dressing gown and slippers just yet!

What makes a Lightning different?

F10/AB/1C/7305 Engine/Gearbox

Bore x stroke: 84 x 90

BHP: 70@ 5,600 rpm.

Highly polished 85 ton Vibrac conrods with caged roller large diameter big end.

Polished flywheels

Polished combustion chamber spheres, ports and valve rockers

Specialoid 13:1 pistons for methyl alcohol fuel

Ignition timing 34 degree advance.

Racing contour camshafts with high lift and long overlap.

Clutch cover with centre and rear cooling holes

Steel oil pump worm gear

21 tooth gearbox sprocket, 45 tooth rear wheel sprocket.

2 x 32 mm Amal 10TT9 carburettors, with inlet ports streamlined and blended to special adapters. Main jets 1700, Needle jets 120, throttle valve No.7

Gearbox: Racing Intermediate ratio, 7.2 bottom gear, double backlash on third and top gear dogs. Ferodo clutch plate. Lightened steel idler gear, clutch shoe carrier, camplate and clutch drum.

Factory tested and waterproof Lucas KVFTT magneto with manual advance.

Dry weight; 380 lb

Nominal top speed: 150 mph.

RC 9205’s cycle parts:

Large diameter experimental finned front brake drums

Ventilated magnesium alloy front brake plates and air scoops

Magnesium alloy rear brake plates

Large fuel tank cutaways for TT carburettors

Racing rearset brake and gear pedal assembly

2 x 44 inch thin gauge sprint exhausts, 1 5/8” diameter circuit exhausts

Lightened exhaust pipe nuts

Racing Seat

Large bore fuel taps with lever

Rev counter and drive; Telltale Stop Needle type with yellow markings

Rev counter bracket and studs

300 kph speedometer with yellow markings

Lightened front and rear solid axles.

Lightened brake cams and torque arms

Tommy bar chain adjusters

Lightning spec front and rear mudguards and braces

Front number plate holder

Cutaway chain guard

WM1 x 21 front alloy rim with 3.00 x 21 Avon ribbed racing tyre

WM2 x 20 rear alloy rim with 3.50 x 20 Avon block pattern racing tyre

10 SWG spokes and nipples

Large bore timed breather hose

Special bronze wheel bearing grease retainers.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook with acknowledgement to Brian Greenfield’s book The Vincent H.R.D. in Australia.

Photos: Jim Scaysbrook, Franc Trento, Charles Rice