I guess it would be impossible today; taking any motorcycle to the Antarctic, let alone an older, likely oil-leaking one. But, it has been done, not once but at least twice in – 1961 and 1968.

I haven’t done definitive research on this, so there may be others who have taken a motorcycle down there, although initial use of Google has found a woman – Benko Pulko – who took a motorcycle in 1997 on a round-world odyssey and another round-world adventurer, David McGonigal who also got his Yamaha motorcycle to Antactica. The 1961 and 1968 visits were by Australians Bill Kellas and Frank Scaysbrook respectively, who were each taking up a year’s posting at the Australian base at Mawson, Wilkes Land, Antarctica. Both decided on a Velocette as their land transport.

Bill Kellas recalls his experiences. “In January 1961, the Danish Polar vessel, Thala Dan sailed from Appleton Dock in Melbourne bound for Mawson Base in the Australian Antarctic Territory, carrying 30 expeditioners, plus round trippers and supplies for more than a year. Deck cargo included a RAAF Dakota (DC3) A65‑81 stripped of wings and propellers, sitting on a special cradle on the main hatch cover. In the hold below was a 350 cc MAC Velocette that had the previous year, been ridden from Perth to Melbourne by George Cresswell.

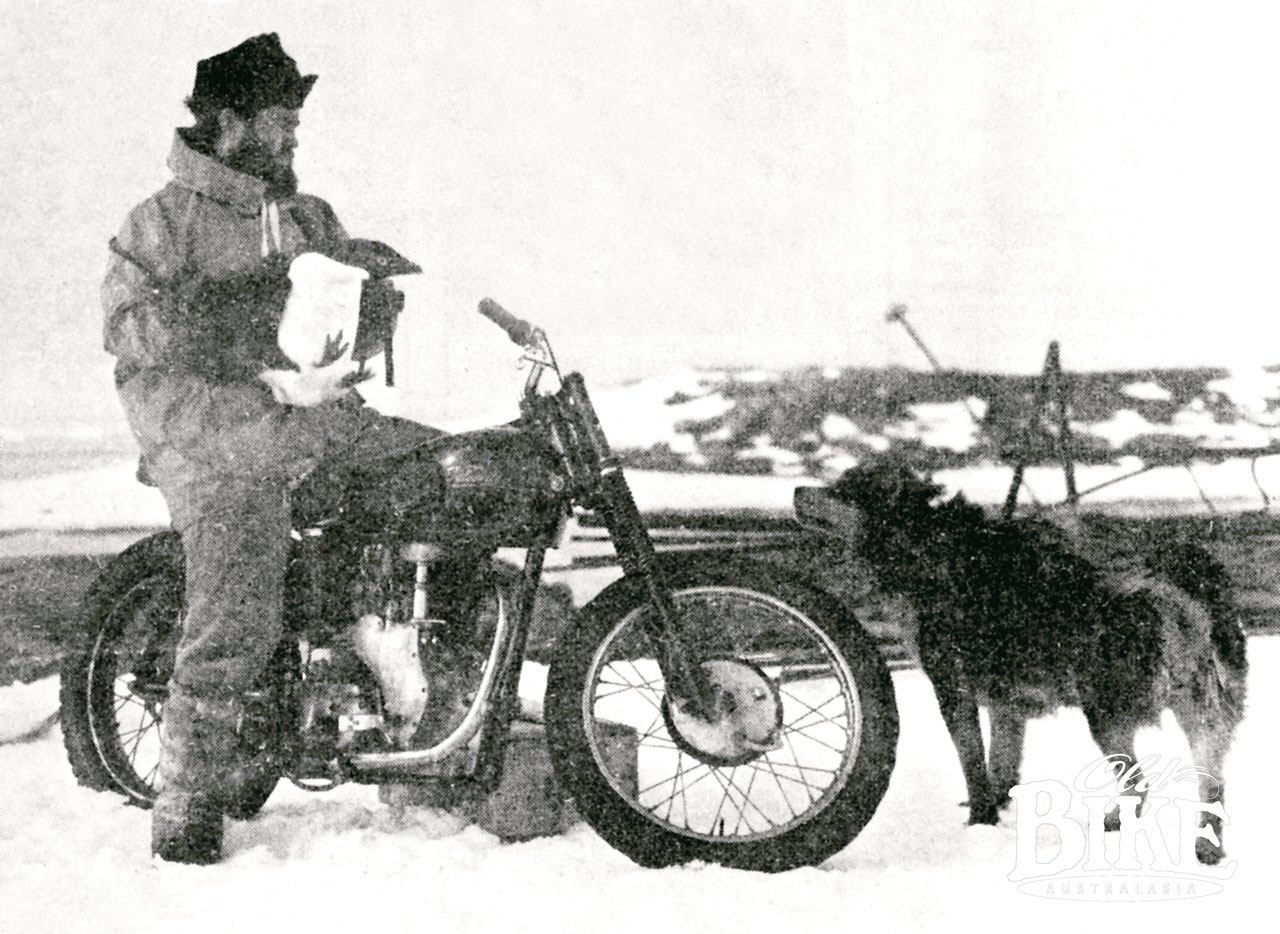

Thala Dan moored in Horse Shoe Harbour at Mawson on 25 January after an uneventful voyage. Unloading the 800 tons of cargo was completed by 9 February after which we were able to relax and take the Velocette for a run around the camp in perfect summer weather. Riding there was difficult over the rock‑strewn ridges around the Harbour and the permanent ice slope behind Mawson was fairly steep and slippery. In late March the sea began to freeze over and within a few weeks the ice depth was 10 inches or more; strong enough to take the weight of vehicles. The coast either side of Mawson as far as one could see, was ice cliffs ranging from 50 to 500 feet along with glaciers, ice caves, and snow drifts overhanging the cliff tops, carved by the wind to every possible shape.

In preference to dog teams or heavy vehicles, the Velocette was used for coastal tours, often towing skiers or a dog sled. It was totally reliable and easy to start even in extremely cold conditions. The only modifications were dry lube on the control cables, lighter oils, a warmer spark plug and a briquette bag tied across the crash bars to protect our boots (Mukiuks) which were not water proof, from slush thrown up by the front wheel. Only a spare spark plug and a few basic tools were carried and on occasion, extra fuel. One other advantage of the Velocette was its relatively light weight and low centre of gravity, when picking it up after a long slide on its side after suddenly encountering bare polished ice at high speed. The Velocette was dropped many times and never sustained any damage and none of the riders was injured. Top speed was 80 ‑ 85 mph indicated, but would have been less due to wheel spin.”

The sea ice was the greatest surface Kellas claimed to have ever ridden over. It is strongest when first frozen and even relatively thin ice supported by water, is incredibly strong if of uniform thickness. As the year progresses the ice becomes thicker in depth, but with the return of the sun in Spring it begins to soften and rot from below. While the surface still looks secure, underneath it is like a soft sponge.

“The Velocette was used, weather permitting, until the middle of June by which time riding was uncomfortable in the low temperatures when wind chill made frost bite a daily occurrence. Clothing was mainly ex‑Army Korean War issue and not designed for bike riding and didn’t include helmets. The Velocette was parked covered in the open until the sun reappeared. In spring with the daylight and temperature increasing, riding resumed as before but caution was required as the sea ice began to soften. In early December the worst blizzard of the year struck with wind speeds exceeding the range of the anemometers (which were destroyed or failed) and visibility reduced to a few feet in drifting snow and ice crystals. This blizzard continued unabated for two days and on the third day was still gusting over 100 knots.

The Dakota and the Beaver aircraft were at the airfield at Rumdoodle in the Masson Range when the blizzard struck. When the wind and drift subsided sufficiently to venture out doors, it was found that the Beaver (which was behind a wind fence) was totally destroyed and the Dakota had broken its tie‑downs and had disappeared without a trace.

A few days later when the weather had cleared, Graham Currie riding the Velocette on the sea ice west of Mawson noticed something red high up on the glacier top. Closer inspection confirmed it was the Day Glow red tail of the Dakota. The plane had been blown by the blizzard about 15 miles down slope at sufficient speed, with brakes engaged, to wear the tyres and wheel rims flush with the skis. It came to rest after the undercarriage dropped into a crevassed area on the cliff top about 400 feet above the sea ice. It had then turned nose to wind and was wrecked.

Because of the crevassing around the wreck site, it was unapproachable for salvage, except by foot with extreme caution. The recovered gear, the Doppler radar, radios, survey cameras along with some aircraft parts were lowered down the cliffs to the sea ice, now very soft and dangerous, to a dog team and the Velocette towing a dog sled. The salvage was completed in two days and on the final run, a 3-foot standing wave of rotten ice was visible chasing the fleeing Velocette and sled.

The total mileage covered during the year was about 3000 miles. Individual trips up and down the coast ranged from local to 50-plus miles. The Velocette was ridden hard to cover the distances quickly, parked while areas were explored and photographed, restarted and ridden home without ever a problem. It was simply taken for granted that it would always get us home again and our faith in the bike was never misplaced. At the completion of our tour the Velocette passed into the hands of our relief party. Beyond that point I have no knowledge of its history.”

Seven years later, it was Frank Scaysbrook’s turn to venture to Antarctica, and with him went another MAC Velocette. Here is his story…

“I spent 14 months in the weather bureau at the Wilkes base, six miles outside the Antarctic circle. Being a keen motorcyclist in Australia and, I guess, a little adventurous, riding down there seemed an exciting proposition. Some of the time the temperature was far too low to go riding, or to do almost anything else outside. The low limit, I found, was about minus 20-degrees F. When I could get out, it was wonderful sport to go charging across the hard snow, but not too fast, for there were always plenty of ice patches where there is simply no wheel grip and you can slide down with the greatest of ease.

The scheme, before I went, was to take the bike to bits, crate it, and build it up when I arrived at base. The engine, front forks and front wheel were salvaged from a light-alloy MAC Velocette circa 1953. Later model swinging arm frame, rear wheel and gearbox were bought second hand in Sydney and various other parts unearthed from various sources. During this period a great feature of Velocettes became apparent – the wide inter-changeability of parts between models and years of manufacture. We boarded the Danish polar vessel, the Thala dan, at Melbourne bound for Wilkes by way of the French station, Dumont d’Urville, located at the south magnetic pole. Below deck, among the mountain of provisions, equipment and fuel, was the crated Velo. After 15 days of battering through the seas of the roaring forties and furious fifties, Thala Dan deposited us at Wilkes. We were 900 miles from the South Pole and 500 miles from our nearest neighbour at Mirny, a Russian scientific base.

Wilkes, established by the Americans for the International Geophysical Year in 1957-58, is a small, rocky peninsula, one quarter mile long and a few hundred yards wide, jutting out from the continent which rises away as a giant white ice-drome as far as the eye can see. Although initially built on bedrock, the plywood huts of the camp complex have gradually become encased in snow and ice, little of which melts through the short summer. The height of the roads, originally on the rock base, has been raised ten feet by ice formation. You get the impression of riding over ancient ruins encased forever in the ice.

Work on the assembly of the Velo began in March. There were no snags, but making the engine plates from 1/4 inch duralumin took a fair time. When the Velo was ready to go, the exit from the workshop’s doorway to the outside world had to be dug through ten fete of snow. Winter was well on its way. Outside, the snow was hard as rock, and apart from the chilly wind, the prospects for motorcycling wee great. After six months or so out of the saddle it was stimulating to slam open the throttle on the fastest vehicle at the camp. Although the Velo was parked outside at all times, its starting habits were impeccable. Running on 80/87 octane aviation gasoline and Long Life oil, three or four swings on the kick starter were sufficient to get the engine firing. What’s more, the clutch freed immediately and crunched gears were unknown.

With a three-day trip to a wrecked Neptune aircraft some miles away in mind, one of the mechanics and I started work on a sidecar – a flat base supported by a converted ski. Alas, before it was finished, a terrific blizzard overwhelmed the camp and that was the last we saw of our handiwork. By that time we were getting near to our departure date for the return to Australia, so we had to content ourselves with trips on the ice plateau inland from the station. It would have bene more fun to race across the flat sea ice, but at Wilkes this area has a reputation for developing cracks large enough to engulf vehicles – including the odd motorcycle used by enthusiasts who were there before I was.”

At the end of Frank’s Antarctic stint, the Velo was shipped back to Sydney, where it still resides in Frank’s brother Dick’s shed. At least it has plenty of other bikes for company.

Story Dennis Quinlan with assistance from Bill Kellas and Frank Scaysbrook • Photos Original colour photography of Bill Kellas’ MAC Velocette courtesy of the owner.