From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 79 – first published in 2019.

Story Brian Fowler and Jim Scaysbrook • Photography Colleen Canning and OBA Archives

For a company so steeped in high performance singles, the concept of the little twin cylinder LE seems at odds with the Velocette ethos. Yet Eugene and Percy Goodman, sons of the founder of Veloce, John Goodman, staunchly believed that sporting singles alone could not sustain the company indefinitely, nor could the utilitarian GTP two stroke. During WW2, Velocette production was restricted to the wartime MAF model, so there was some time to think ahead to the days when normal service would be resumed.

Eugene Goodman had sketched early concepts of what would become the LE (which he referred to as the Motorcycle for Everyman) during the ‘thirties, and Phil Irving frequently added his thoughts before he departed for Vincent-HRD, but it was Charles Udall who converted the growing paper file into proper working drawings to enable production estimates to be undertaken. As early as the British winter of 1944-45, a hand-built prototype of the LE (“Little Engine”) was nipping around the Velocette works at Hall Green, Birmingham, and in almost every respect, it bore no resemblance to any previous model. The stated aim was to attract new customers – rather than existing or traditional motorcyclists – to the market, and to achieve this, much of the orthodox thinking had to be abandoned.

In its original form, this unusual-looking creation strayed from convention in order to satisfy the aims of the project, which in no particular order included; weather protection, clean running, ease of starting, quietness, long service intervals, ease of maintenance (particularly for the non-technically minded), luggage capacity, economy of operation, easy cleaning and long overall life.

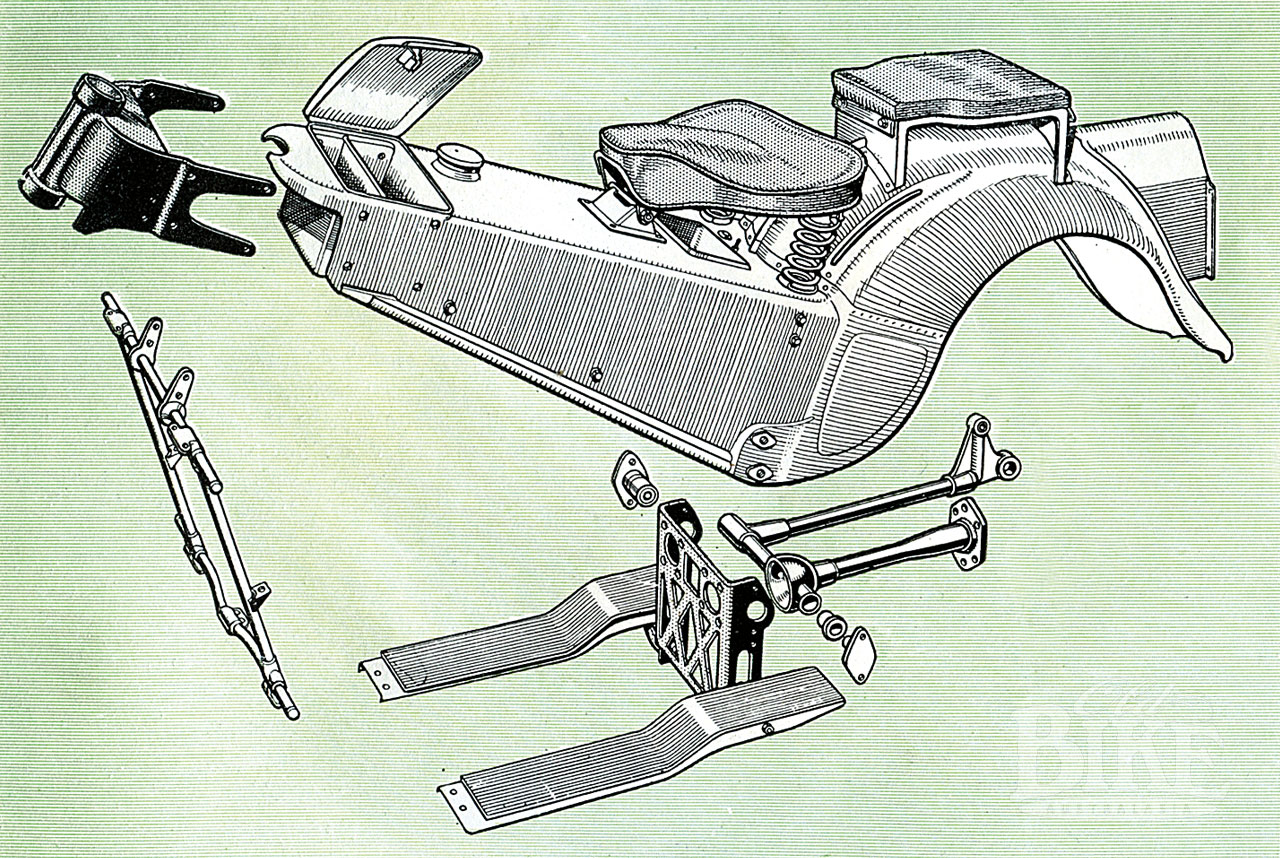

The heart of the mater was the frame, or rather, chassis; a single unit comprised of pressed 22-gauge steel sections welded together, containing compartments for the petrol tank, battery (accessible by unbolting the saddle springs and tilting the seat forward) and tool box, and into which the unit comprising the engine, transmission, final drive and rear suspension was slotted. The 1.25 gallon (5.6 litre) fuel tank bolted inside the main pressing. To achieve the aim of weather protection, built-in leg shields and floorboards kept water and road muck away from clothing, with voluminous front and rear mudguards – the latter built as part of the chassis. Velocette had in 1939 purchased a Lake Erie hydraulic press, capable of producing large pressings, which in addition to pumping out the chassis and mudguard components for the LE, was used for contract work by other manufacturers. Comfort dictated the use of rear suspension, and Velocette were already well-versed in this with the highly successful MK VIII racing model with its swinging arm rear end. The top mountings for the suspension units moved in a channel so that they could be adjusted according to loads such as a pillion passenger – a system patented by Veloce in 1939 and subsequently used on all post-war swinging arm models. After considering a proprietary Webb front fork, Velocette made their own to a completely new design.

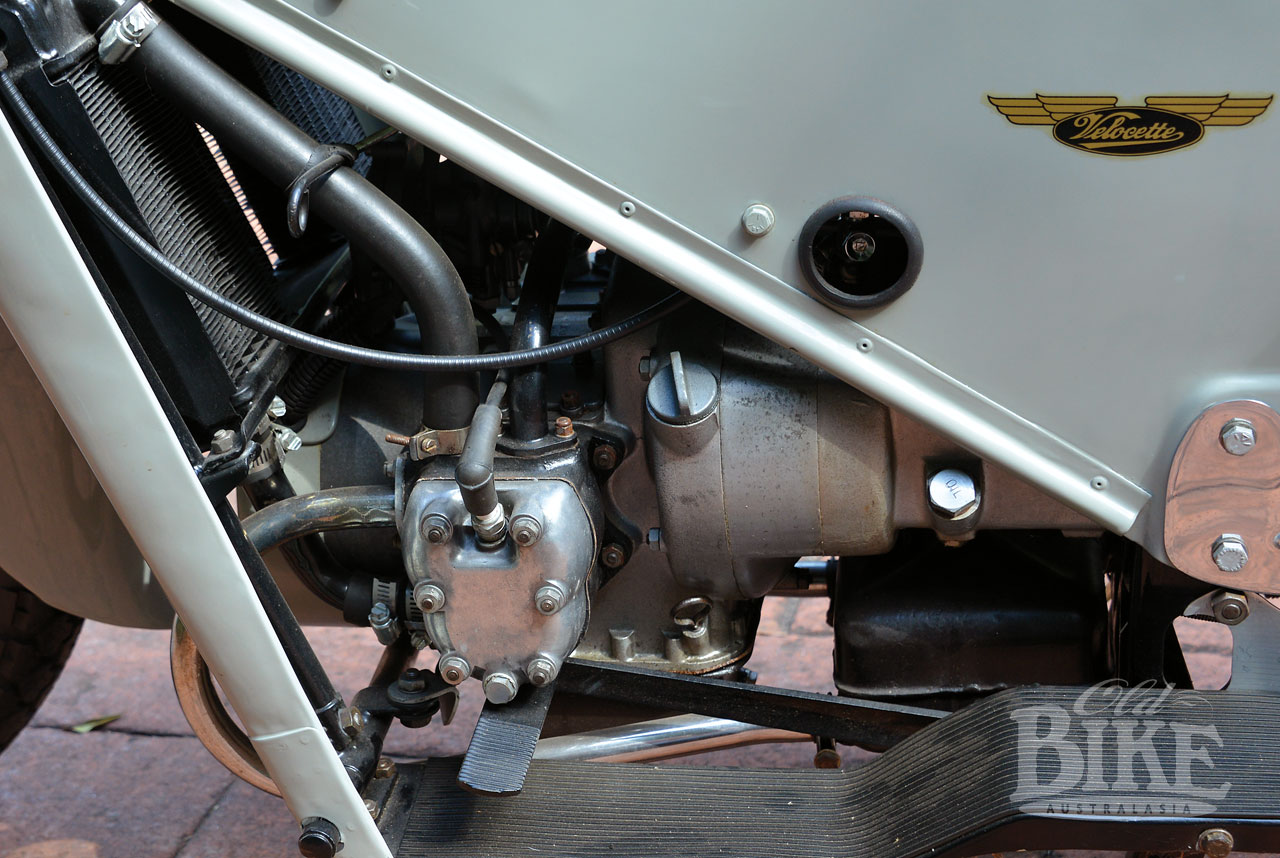

The engine itself, of 149cc with a bore and stroke of 44mm x 49mm, side-valve twin cylinder horizontally opposed, was water-cooled, necessitating a radiator and associated hoses, which were largely hidden from view. The water jacketing around the cylinders and heads enhanced the exceptional quietness, and because of the liquid cooling, large leg shields and a voluminous front mudguard (which would normally have restricted cooling air) could be used in the quest for weather protection. The use of side valves kept the engine width down to just 14 inches (35.5cm). A special seven-jet carburettor was designed by Udall and manufactured by Amal, but it took 12 months of painstaking development before a satisfactory Purolator-type fuel filter could be developed which could trap impurities before they reached (and clogged) the tiny jets. Mounted above the crankcase, the carburettor sat on a long inlet tract connecting the two cylinders, with air supplied via a filter situated in the centre of the radiator. A three-speed gearbox with a two-plate dry clutch, built in-unit with the engine, connected to a shaft drive with a bevel drive set into the left side leg of the swinging arm rear fork, with fully sealed internal lubrication. Gear changing was done by hand, with a car-style gate housing attached to the right side of the chassis. Both engine starting and gear change were hand operated – apparently to avoid scuffing the rider’s footwear – and the engine could be started in gear by pulling in the clutch lever. Electric starting was considered but discarded on the basis that it would require too large a battery and dynamotor.

Within the front of the crankcase sat a fully integrated ignition with a single HT coil and distributor, and DC generator (plus a permanent magnet to permit the engine to be started even with a flat battery) – all especially made by BTH, while the carburettor incorporated a cold-start mechanism to avoid the need for ‘tickling’ with the subsequent messy dripping of petrol. The entire engine and transmission, along with the quickly-detachable rear wheel and shock absorbers could be removed as a single unit. Each engine assembly was built on a single floor track by teams of four fitters, then run for nine minutes at the end.

Initial projections were for a production of 300 complete LEs per week (with 80% exported), and to achieve this formidable target, the rest of the Velocette range was trimmed to just the 350cc MAC – a profitable and good selling model. In reality, the LE production was wildly optimistic and generally reached less than half the target. Prior to commencement of production in 1948, exhaustive testing was carried out in order to ensure that the machine would be completely de-bugged by the time it reached its new owners. In the days of severely rationed ‘Pool’ petrol, just obtaining sufficient fuel supplies was a tricky situation, which severely affected the testing schedule. For the 1948 model year, UK price for the basic model LE was £126, compared to just £76 for a BSA Bantam. The Australian price, including 8.5% sales tax, was announced at £188. The official unveiling for the LE took place at the Earls Court Show on November 18th, 1948, and despite scarce financial resources, Veloce took out full page colour ads in both major weekly magazines to herald the new arrival.

Alas, despite the considerable road-testing, shortcomings and defects came to light soon after deliveries began in October 1948. The most serious of these were mechanical failures that were traced to condensation within the engine unit leading to contamination of the lubricant. This was particularly evident when the LE was used for short runs, which was, after all, one of the primary purposes. As quickly as possible, a series of fixes was implemented, and because ball and roller bearings were particularly susceptible to moisture failing, Eugene Goodman dictated that these were to be replaced with plain bearings (and an oil-pressure gauge) as a matter of urgency. This went part of the way to solving the problem, but by late 1953, the crankshaft with its main bearings and big ends was converted to pressure-feed.

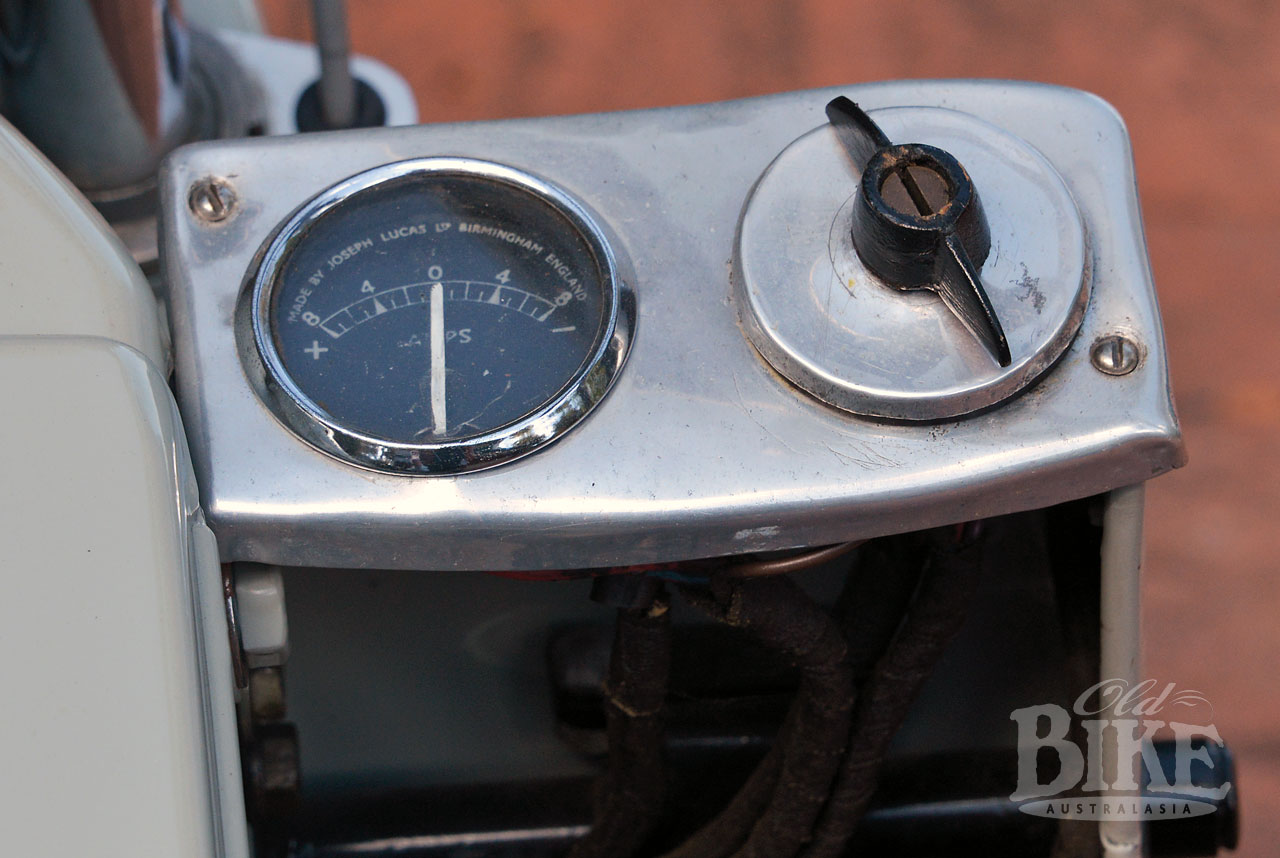

Complaints arose as well about the overall lack of performance, and with 245lb (111kg) to push around, the little 150 had its work cut out. By November 1950, a new LE (marketed as the LE 200 or LE Mk II) with the engine increased to 192cc (achieved by increasing the bore to 50mm) was ready. The new model, although visually identical to the original, incorporated a more robust crankshaft, more efficient cam design, much-increased oil pump capacity, an extra plate in the clutch, and improvements to the final drive of the transmission. Despite the increased capacity, petrol consumption was also improved, to around 120 miles per gallon. Problems also occurred with the BTH ignition/power system, and eventually this was replaced with a new 42 watt AC generator-ignition unit made by Miller, who had supplied Veloce with lighting equipment for many years. Weight increased slightly to 250lb (113.3 kg).

In 1955 a new die-cast aluminium-alloy swinging arm assembly replaced the tubular steel item, which had shown a tendency to crack after long periods of use. In the same year, an attractive range of two-colour décors was offered, making a welcome change to the rather drab grey used on the original models. A plush two-level dual seat (with a 71mm seat height for the rider) also replaced the sprung saddle and pillion pad, and 18 inch wheels with 3.25 inch section tyres replaced the earlier 19 inchers. As well as the existing Leathercloth panniers, new “Streamlined” two-piece steel panniers were offered as extras.

Announced in late 1957 the MK III LE featured full-width aluminium alloy hubs in place of the pressed steel 5-inch units, a larger headlamp which was faired into the handlebars which were themselves revised with a wider, more comfortable sweep, an ignition/lighting switch carried in the headlight along with an ammeter and speedometer. The most significant change was probably the new four-speed gearbox, along with the change to a kick starter and foot-change gear lever, both on the right hand side. An Amal 363 Monobloc carburettor became standard fitment, and the heavier crankshaft from the new air-cooled Valiant model was adopted, giving even smoother running. 12 volt electrics were also offered as an extra and standard on the models supplied to the UK Police Force.

At one stage, more than fifty police forces throughout UK relied on the LE, some having more than 100 in the fleet. In fact, the versatile LE, with its ability to run at low speeds, was very instrumental in drastically reducing the old walking police beats, freeing up manpower and speeding up the whole exercise at the same time. It was found that one police rider could do the work of three men on foot. The LE was even more useful for police work when fitted with a two-way radio, and for this purpose Miller produced a larger generator to keep the battery fully charged when the radio was in continuous use. At its peak, police orders accounted for nearly half the total LE production. The UK postal service was also supplied with a number of LEs, painted red.

In police guise, the LE gained the nick-name of Noddy Bike, which was apparently coined because metropolitan police officers were required to salute their superiors. However in order to obviate the need to take one’s hand from the handlebars, officers were allowed a polite nod instead.

In 1963 Veloce introduced the Vogue, a restyled LE with fibreglass bodywork made by Michenhall Brothers, who also supplied the fibreglass components to the Rickman brothers for their Metisse road and racing motorcycles. Twin headlights were used on the Vogue, along with directional indicators. The Vogue however was a complete flop, with just 381 built over a four-year period. On the final iteration of the LE, Lucas electrics replaced the Miller system, giving far better lighting.

But the end was nigh for Velocette, and the famous company finally closed its doors on 3rd February, 1971, with the last bikes to leave the factory being a batch of LEs. In hindsight, the LE was a brave venture that never really paid off. It is believed that the projected profits after amortisation of set up costs were never realised, and the discounted fleet sales to police and others barely covered costs. Nevertheless it was a standout model in motorcycling history, with many innovative features that found their way into other makes over time. In reality, Velocette, which remained a small family-operated business throughout its existence, never had the resources to service their considerable investment in the LE. As the model atrophied, even the old 500cc singles were reintroduced, ironically sustaining the company for a few more years. Today, the LE looks as quirky as ever and is quite collectible, the silent little side-valver that remains an outstanding example of original thinking.

An owner’s opinion.

We have featured two of Bryan Fowler’s motorcycles previously in OBA, and here’s the third in the set. Bryan’s LE is a 1956 Series II (192cc), and he describes its history and highlights.

This LE was originally sold by Pride and Clarke of London, to a commercial pilot who carried the machine with him on flights as personal transport. It was registered in Singapore, travelled extensively (ok, so mostly as stowage!) and several repairs to leg shields etc, are indicative of aeroplane style maintenance. Upon his retirement, the original owner and his son began restoring the LE but his untimely death led to it being put up for sale. I purchased it in 2004 from England, had it shipped to my home in the U.S. and set about restoring it.

Being both an ardent history buff as well as motorcycle enthusiast, there are three British motorcycles which, to my mind, typify immediate post war radical thinking, the junction of: a slate wiped clean, new engineering practices/knowledge and a scarcity of personal transport. The three are: Sunbeam S7, Ariel Leader and the LE. Having already restored a Sunbeam S7, the LE was my next purchase. While some readers may be shaking their heads, it has been my experience that more often than not, those who shake their heads at these motorcycles have rarely owned, ridden and/or maintained one.

From a maintenance perspective the LE is user friendly, once of course you understand its idiosyncrasies (and shelve your own), not the least of which is its torsion box frame. However, in a matter of minutes, the frame complete with front end/wheel etc, can be removed providing unfettered access to the radiator, engine, gearbox, rear wheel, and so on, as they form a stand-alone unit. In terms of maintenance I don’t think it gets any easier than that. The side valve, water cooled, opposed twin is a jewel of an engine, and rarely is anything larger than a ½” Whitworth spanner required. All typical adjustments such as valves, and contact points are straight forward and accomplished with minimal fuss at 20,000 mile intervals. After 60,000 miles, the more major component re-builds are also straightforward and you won’t strain a muscle while handling these. By the standards of its day, the service intervals are themselves both user-friendly and bespeak to the engineering quality inherent throughout the LE.

Riding the LE

Yes, there are two handles protruding from the right side of the engine, the outer, larger one is the hand starter while the inner, smaller one (mounted on the body) is the hand gear shift (ironic given Velocette pioneered the positive-stop foot shift). The hand starter was intended to avoid “Everyman” scuffing their shoes on a kick starter and on the smaller (150cc) Series I LE, the hand starter was integrally connected to the centre stand. As simple as: pull hand crank to start the engine and centre stand automatically retracts while you ride away. The hand gear shift was purposefully utilised as potential buyers/riders, new to motorcycling, would presumably be familiar with such from driving a car.

From cold, the choke lever is pulled out on the left side, hand gear shift in neutral (mid notch between all up/all down), hand crank pulled several times, with ignition off to prime the engine, switch ignition on and 1-2 pulls and the engine invariably fires up, thanks in part to battery/coil ignition, once warmed (this may be a few minutes given it’s water cooled), choke pushed back in and you’re good to go. You may actually have to strain your hearing to discern the engine is in fact, running and relatively vibration free owing to its Isolastic mounting. I have actually ridden my LE amongst swap meet spectators and have been able to pull along side them and touch them-without them hearing my approach.

Given its low seat height and low centre of gravity, both feet are firmly grounded when you’re seated. The relative light weight of the LE combined with its low centre of gravity give it a nimble, almost “flickable” feel, while the handlebar geometry is almost like that of a very early motorcycle as they are somewhat shaped to pull back towards the rider, almost “armchair” like. With the conventional left hand clutch lever pulled in, first gear is selected by pushing the hand gear shift forward (or downwards), clutch released, throttle increased and away you go. Second gear (quickly needed) is accomplished by pulling the gear lever back towards you and takes you up to 30 mph. Obtaining third gear is a bit trickier as you have to both push the lever down and inwards (towards the LE’s body) but once done, an almost silent 30-40mph cruising speed is comfortably, and thoroughly obtained and enjoyed. Having started motorcycle riding on hand shift/foot clutch WLAs, the LE’s hand gear shift isn’t too challenging for me but can be for some. Also reminiscent of my WLA and equally comfortably, your feet readily find the foot boards (which also extend back for a pillion passenger). The left foot rear brake pedal is parallel to the footboard and your foot naturally finds/operates it. The right handle bar front brake is also easily accessed.

The rider’s peripheral vision is somewhat tested by having to both look forward (I’m told its safer that way) while also trying to see the speedometer which is mounted in the top of the left aluminium leg shield. Equally so with the ammeter which is mounted in the top of the right leg shield (as is the ignition/lighting switch). Having said that, it’s doubtful many riders will be overly concerned about excessive speed nor a potential stop or ticket by a non-Noddie bike mounted officer of the law. The brakes are commensurate with the LE’s speed, ie; they are fully adequate for the speeds attained (aside from down hill). Downshifting from 3rd to 2nd (as with upshifting) is a bit of an acquired knack, but readily mastered with experience. Further downshifting from 2nd to 1st is best done at a standstill.

As with most vintage motorcycles the rider is best to consider the context (roads, traffic, speeds etc) in/of which the motorcycle was made and drive accordingly. The LE is at its best and most enjoyable on back country roads as it is then that the rider has the unfettered opportunity to fully appreciate the LE’s attributes and thereby better understand Velocettes’ outstanding engineering, design and forethought. As C.E. Titch Allen noted, “the LE is an economy lightweight which ended up as the most sophisticated pure design in motorcycle history.”

Anecdotally, I recall speaking with several retired Canadian Police Officers who were issued LEs as Police Bikes. Suffice to say, in the land of Harleys and Indians, they were not amused. To avoid having to ride the LEs, they set the front wheels against a brick wall, put them in gear and revved the engines until they experienced a “catastrophic failure”. In their minds, it was better to risk a dressing down by a commander-than the embarrassment of being seen on an LE.

Setting aside the “quirky” appearance of the LE, and perhaps even forgetting it is a motorcycle, the close scrutiny of its overall design and build reveals that this is a complete product of, and by, engineers, not of boardrooms or consultants. Its engineering is tried and true, if anything it is overbuilt, yet in many respects, it is not dissimilar to that of the traction and hit/miss engines of a different era-many of which are still running. To conclude, perhaps the LE’s fate is not unlike that of my 1951 Crosley microcar, as it too was designed to be a vehicle for “Everyman”…the problem being, it seemed, was that “Everyman” didn’t want to be reminded they were…an “Everyman”.

Specifications: Velocette LE Mk III (Final version 1958 – 1971)

Engine: horizontal opposed twin, side valve, water cooled.

Bore x stroke: 50mm x 49mm

Capacity: 192cc

Compression ratio: 7.0:1

Power: 8hp at 5,000 rpm.

Carburettor: Amal 363 Monobloc

Ignition: Battery and coil

Generator: Miller AC4 flywheel alternator. 6v 42 w output.

Gearbox: 4 speed foot control

Transmission: Shaft with spiral bevel

Wheels/tyres: 3.25 x 18 front and rear

Brakes: 5 inch front and rear

Weight: 119kg