Rivalry in motor sport is not uncommon. But in the case of the long defunct Gnoo Blas circuit in Orange, 285 km west of Sydney, motor racing was simply the common factor in an intense contest with the neighbouring town of Bathurst, just 60 km back down the road. Both Bathurst and Orange had populations of similar sizes, around 18,000 each in the early 1950s, but Bathurst had one thing that Orange did not – Mount Panorama.

Built as a scenic drive over the area originally known as Bald Hills, ‘The Mount’ had become Australia’s premier circuit from the moment it opened in 1938. But the war took its toll on the venue, and little in the way of maintenance or improvements had been done by 1952. The promoters of the annual Easter car races, the Australian Sporting Car Club, had been at loggerheads with the Bathurst council for years, threatening to abandon their traditional meeting unless changes were made. The pits and paddock area in particular, was a disgrace – the slightest shower of rain turning the entire area into a sea of mud. The road surface too had seen better days, with crumbling edges and numerous potholes that were routinely filled with asphalt until the sealed area resembled a patchwork quilt. Bathurst Council drove a further nail into relations by doubling the surcharge on each spectator ticket.

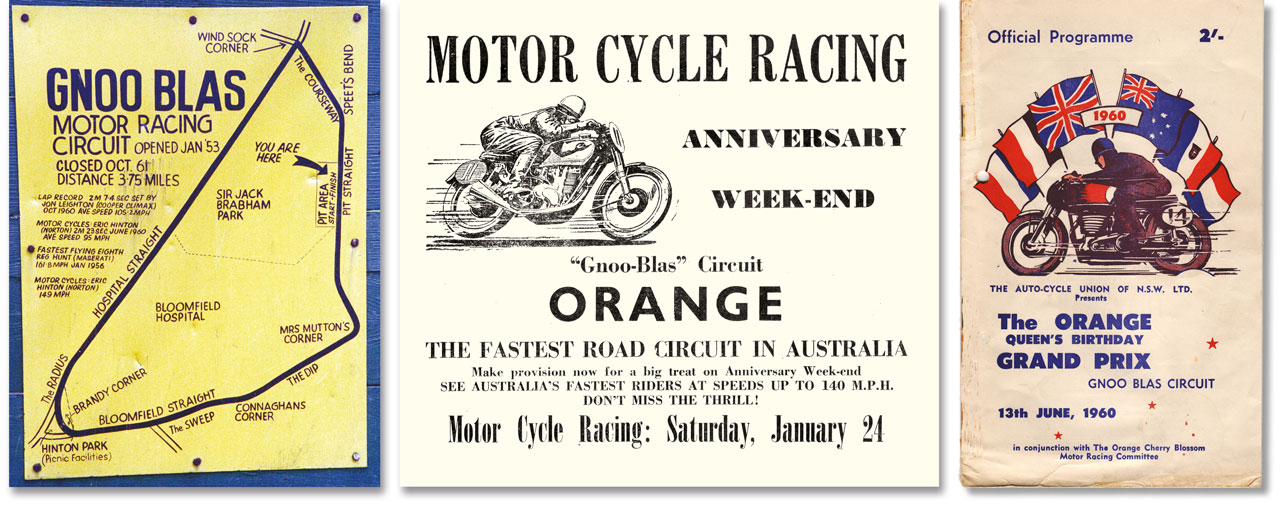

After the Easter 1952 meeting the ASCC was fed up, and this time it had a new arrow in its quiver. After a series of not-so-secret meetings with the Orange City Council, the ASCC announced it would not be back at Bathurst at Easter 1953, leaving the weekend as a motorcycles-only fixture. In a short space of time, a 3.75 mile stretch of public gravel roads to the south of Orange was mapped out and tar-sealed using mainly volunteer labour. The track was christened Gnoo Blas, meaning ‘twin shoulders’ in the local aboriginal dialect – a description of the two mountains, Canobolas and The Pinnacle, that overlooked the area. A date of October 1952 was announced for the opening meeting. This came and went after savage winter weather delayed the completion of facilities, but all was in readiness for the January 24, 1953 – not for cars, but for the Orange Grand Prix for motorcycles.

Roughly triangular, the circuit had some gentle rises and falls but was basically flat, with Bloomfield Mental Hospital located on the inside of the southern section and the Tiger Aerodrome in the northern infield. As a layout, about the only thing really going for Gnoo Blas was that it was extremely fast, with two basic right angle corners and a 120-degree right hander (Windsock Corner) at the end of the main straight. The most challenging section came halfway around the lap where the road flicked right, then left (Connaghan’s Corner) over Brandy Creek at a section known as The Sweep. The track then ran uphill to Brandy Corner before swinging hard right onto Mental Straight – a 2 km flat out blast back to Windsock and the start/finish area.

Like Mount Panorama, spectator traffic was obliged to use the racing circuit to access the vantage points, of which there were few, and this naturally led to much vehicular congestion on race days, particularly the opening meeting when systems were new and untried.

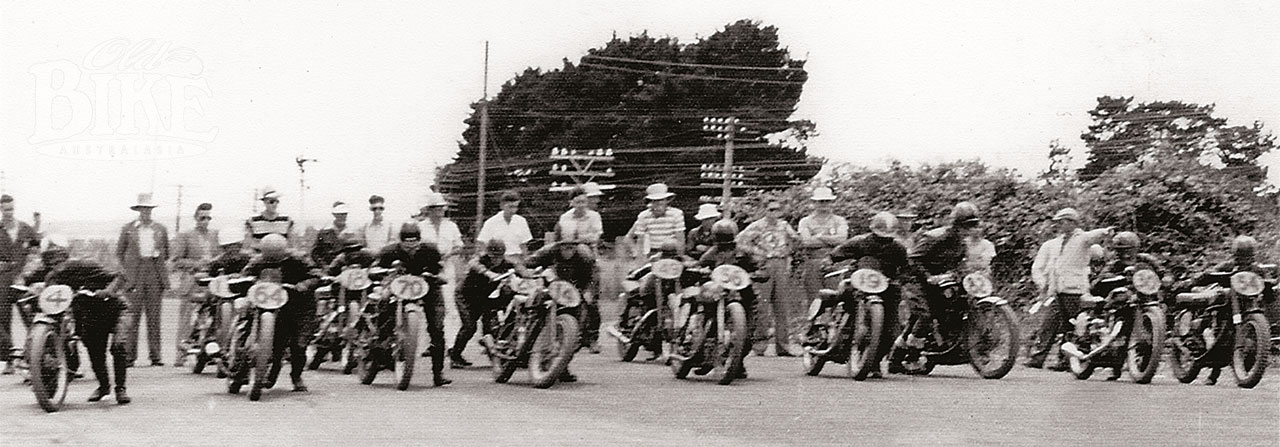

At this time, motorcycle road racing was in a parlous state in NSW, with only the annual Bathurst Easter meeting until Mount Druitt opened in November 1952. So it was with great expectation that the Orange date drew nearer; the entry list headed by Harry Hinton Senior and his sons Harry Junior and Eric, Keith Bryen, Sid Willis, Lloyd Hirst, Jack Ehret, Tony McAlpine and the rising star Alan Boyle from NSW, Victorians Maurie Quincey, Charles Rice, Col Stewart, Ray Owen, George Murphy, Bernie Mack, Owen Archibald, Roger Barker, Noel Cheney and Col Brown, and versatile South Australian Laurie Fox. The lure of £1,000 prizemoney ensured a bumper entry in all classes.

A nine-event program was set down for Saturday January 24th, but with the aforementioned traffic problems, the meeting was nearly one hour late in getting under way. First event run on the circuit was the Junior Clubmens’ Division B, a fairly processional 8-lap affair led all the way by J. Fisher from Les Schultheiss and Fred White in a Velocette 1-2-3. Replacing Quincey on the Walsh Bantam, Ballarat’s George Morrison simply disappeared in the Ultra Lightweight to win from A. Patterson and Col Brown, while Johnny Shanks similarly disposed of the opposition in the Senior Clubmens’ Division B. The first of the ‘title’ races, the 10-lap Lightweight GP was next, where Harry Hinton, on his self-built 250 OHC Norton, did his chances no good by fluffing the start and having to thread his way through the pack while Sid Willis and Alan Boyle fought out the lead. Despite Boyle’s frantic attempts, which included lying prone on the Velo along Mental Straight, Willis eventually pulled away to win comfortably, with Hinton slipping past Fox, on the ex-Fergus Anderson 250 Guzzi.

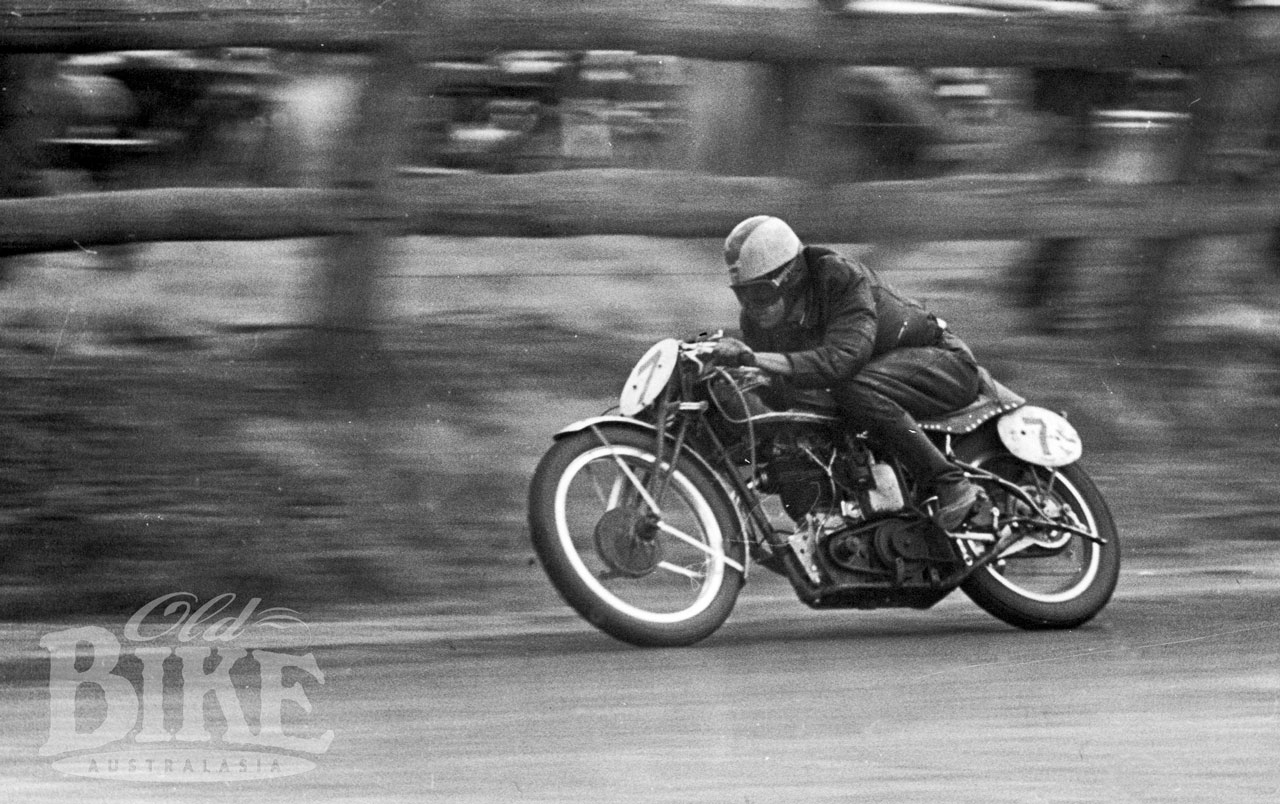

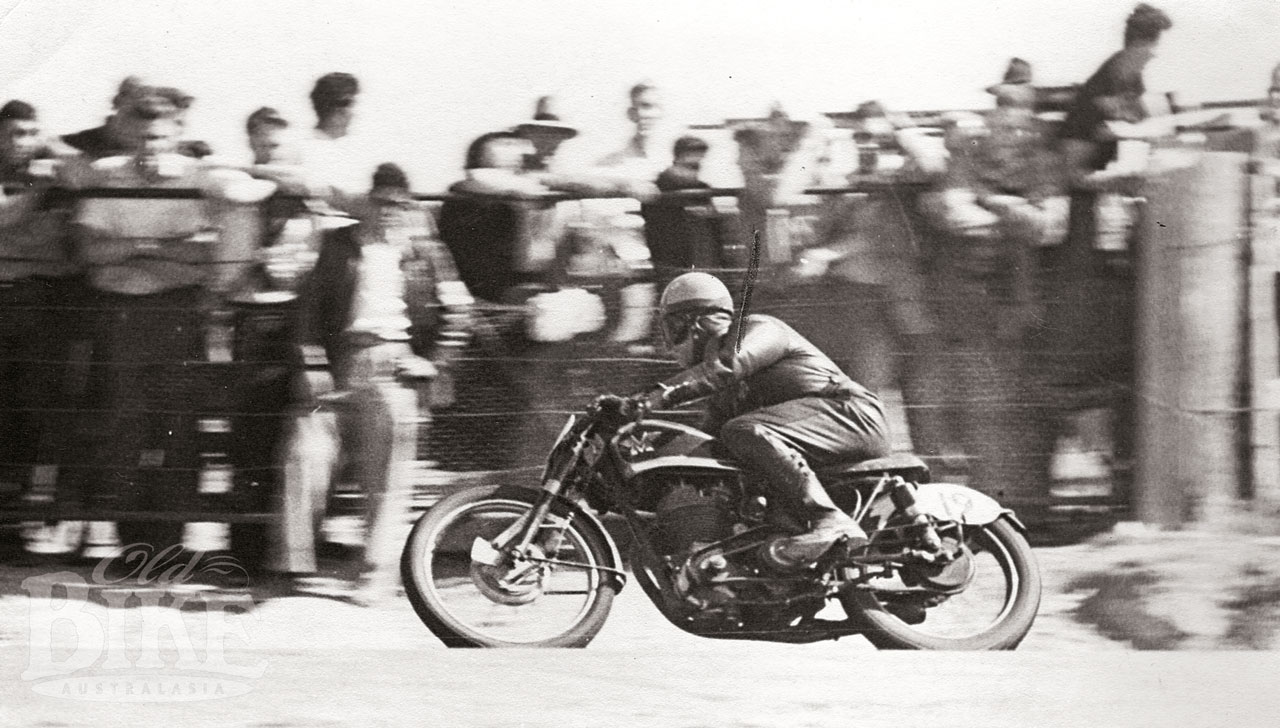

In the closest finish of the day, young Eric Hinton beat Len Roberts by a bike’s length in the A Division of the Junior Clubmens’, and then it was time for the much-anticipated Sidecar Scratch, which incorporated a sealed handicap. The win was bound to come from one of five 1000cc Vincents entered and it was Victorian George Murphy who led from start to finish on the ex-Frank Sinclair HRD. After a terrible start, Jack Ehret tore through the field to displace Lloyd Hirst on the final lap, with Laurie Fox fourth on his 600 Norton. Murphy also took the handicap honours. After a lengthy lunch break, the first of the 20-lap blue-ribbon solo events, the Junior GP, lined up. Fresh from his win in the Australian TT at Little River just a few weeks previously, Alan Boyle, on Les Slaughter’s potent Velocette KTT was in a determined frame of mind but it was Tony McAlpine, showing the benefits of his recent overseas experience, who took the early lead. By lap 2 Boyle was in front, but had Quincey all over him – the battle raging for several laps until on lap five, Boyle made a brave move to pass the Victorian at Connaghan’ Corner, the flat-out plunge to The Sweep. The road was simply not wide enough for the move, and Boyle’s KTT drifted off the tarmac, struck a culvert and somersaulted through the trees, inflicting fatal injuries on the 24-year old rider. While Quincey and McAlpine continued their battle, Hinton joined the leading group and took over at the front at half distance. He held the advantage to the flag but Boyle’s tragic accident had cast a pall of gloom over the meeting. Victorian Charles Rice, on his well-prepared Matchless, narrowly won a thrilling dice for the Senior Clubmen’s A Division over Len Roberts, before the final race, the 20-lap Senior GP, gridded up. The race catered for machines of unlimited capacity, and with the sidecars removed from their Vincents, the Black Lightnings of Lloyd Hirst and Jack Ehret shot to the lead and stayed there. Chased forlornly by Hinton’s 500 Norton, the first three all lapped at more than 90 miles per hour average, making Gnoo Blas the fastest circuit in the country, and lapped the entire field in the process. Ehret had the honour of setting the first outright lap record for motorcycles at 2 minutes 27 seconds, an average of 92 mph (148 km/h).

The unfortunate media coverage generated by Saturday’s fatality resulted in a bumper crowd of 15,000 for Monday’s car races, and the organisers of the combined meeting, the Cherry Blossom Festival Committee, professed to be happy enough with the outcome of the weekend, notwithstanding the hassles with spectator movement. However there was much rancour within the ranks of the ASCC, and a splinter group, calling itself the Australian Racing Drivers Club, broke away and headed back to Bathurst to resume the traditional Easter Monday date for 1954.

Meanwhile, a second motorcycle meeting, the Orange Grand Prix, with £750 prizemoney, was announced for Saturday October 3rd, 1953. An idea was also floated to hold the Australian TT at Orange at Easter, 1954 as an alternative to Bathurst, with Orange Council dangling an attractive financial package to the ACU. Bathurst Council countered by reducing the hiring fee for Mount Panorama from £250 to £50. The Bathurst Chamber of Commerce also pitched in with financial support, and the Orange offer lapsed.

By October, much of the circuit had been resurfaced by the local council, a move that created vocal opposition from ratepayers. Come race day, a miserable crowd of around 2,000 turned out, resulting in a further substantial loss (the opening meeting also lost money) to the Cheery Blossom Committee. Division One of the Junior Clubmen’s GP opened the program, and produced a thrilling dice between Eric Hinton and Wal Blackburn, with Jack Harris third some way back. The 125 and 250 GPs were combined; the smaller bikes doing 4 laps and the 250s 6. Keith Conley’s Lambretta was a clear winner in the tiddler class, while Hinton controlled the 250 (in the absence of Sid Willis who was racing in Europe) to win from Allen Burt and Tamworth’s Harry Pyne. Eric Hinton made it two from two by winning Division One of the Senior Clubmens’, while BSA-mounted Tom Delaney took out Division 2 of the Junior Clubmens’. As usual the big Vincents had the legs on the field in the Sidecar race, Jack Ehret winning form Col Cheffins. The stars were on the grid for the Junior Grand Prix, and the early running was made by Keith Stewart’s 7R, from Bob Brown’s KTT Velocette. But when it suited him, Harry Hinton Senior simply steamed past and pulled away for the easiest of wins. Terry O’Brien from Inverell and Ralph Raynor from Dubbo, both Triumph mounted, diced for the lead in the Senior Clubmens’ Division 2 for the entire six-lap race, the decision narrowly going to O’Brien in the closest finish of the day. At 4.15pm, a small but quality field lined up for the feature event, the Senior Grand Prix over 15 laps. The big question was whether Hinton’s works-engined 500 Norton could hold the Vincents of Ehret and George Slaughter, but this was answered within the first lap when the ‘Old Master’ bolted into the lead and stayed there. Behind, Jack Ahearn’s Norton was holding the two Vincents until Campbell pitted for fuel and Ehret retired . In an effort to go through the race without a fuel stop, Ehret had built an extra tank into a streamlined tail-piece, but it sprang a leak, pouring fuel over the rear tyre. At the finish, Hinton had lapped every one except Ahearn, with Stuart Simpson’s 500 Velocette third.

Although a third meeting was mooted for January 1954, the mounting losses on the motorcycle events meant the organisers were unwilling to bankroll such an event, and the bikes disappeared from Gnoo Blas. The car races continued, with the pits moved to the inside of the circuit and more resurfacing carried out in an attempt to quell the unrest about the circuit’s shortcomings.

When the dreaded NSW Speedways Act came into being in 1958, it forced the Gnoo Blas organisers into a decision on whether to spend a considerable amount of money upgrading the circuit, or to abandon it. The Cherry Blossom Committee made strong representations to the ACU of NSW for financial assistance in return for one or two guaranteed motorcycle meetings per year, but their requests were turned down. The work went ahead anyway, and a date of November 8, 1959 listed for a motorcycle meeting, but the ACU failed to inspect or licence the circuit, meaning the meeting had to be abandoned. This caused howls of protest from among the NSW racing fraternity, who claimed with some justification that the ACU were protecting their own interests at Bathurst. With Mount Druitt gone, motorcycle road racing was back in the doldrums, with just one meeting per year in NSW.

Finally, the circuit was re-licenced in early 1960, and the bikes returned on June 13. Staging the event in central western NSW in the middle of winter was a gamble, but the Queen’s Birthday Holiday weekend was deemed to be the only suitable time in order to minimise traffic disruption with the necessary road closures. True to predictions, it was a bitterly cold experience, with the temperature on the Monday race day reaching just 5 degrees. During practice, Eric Hinton lapped at 2.25, under the record, but said he could have easily done better had he not been ‘frozen stiff’. In front of a dismal crowd, Monday’s program opened at 9.30am with the Ultra Lightweight; an event that had taken on a different look with the proliferation of the new Honda twins – seven of which were on the grid. The four lap race was a flag-to-flag victory for Brian O’Connor’s Honda, leading home Kel Carruthers’ Bantam BSA. Brian Smith’s Velocette easily took out the Non-Expert Division Two, which was followed by the Lightweight GP. The NSUs of Eric Hinton and Ray Blackett had no trouble seeing off Carruthers’ special 250 Norton, with Eric clearing out to take an easy win. Jack Saunders’ Triumph took out the Unlimited Non Expert Division One, then it was time for the Junior GP to line up. This looked to be a much closer contest, with Jack Ahearn riding at the peak of his form, but once again, Eric Hinton’s scruffy but rapid Norton simply cleared out to win from Carruthers and Ahearn. Only four outfits greeted the starters flag for their 5 lapper, with John McManus and passenger Dennis Fry taking out the race from Nev Stumbles, who had to do a U-turn back to the grid to retrieve his passenger who had fallen out! Brian O’Connor, this time Norton-mounted, scored his second victory of the day in the Unlimited Non Expert Division Two, and rising star Peter Fitzpatrick did likewise in the Junior Non Expert. By the time the 10-lap Unlimited GP formed up on the grid, only the hardiest souls were still on the fences. Once again, Hinton bolted from the start and smashed the lap record on his way to a comfortable win over Ahearn and Blackett. The ACU Steward, Harry Bartrop, claimed Hinton had been timed at 128 mph through the speed trap on the main straight, and his best lap of 2.23 constituted a new outright lap record of just on 95 mph (152.8 km/h). Despite poor spectator attendance, the ACU announced that it had ‘just about broken even’ and would promote a further meeting on October 3, 1960. As the date drew nearer, it became apparent that the ACU had lost interest in the venue, and the meeting became a cars-only affair where Jon Leighton set what was to stand as the all-time lap record for the circuit in a Cooper Climax at 2 minutes 7.4 seconds – just short of 106 mph (170.5 km/h).

With new, permanent circuits springing up all over the place, the days of pure road racing on big open courses like Gnoo Blas were well and truly numbered, and the circuit passed into oblivion with barely a backward glance.

A lap around Gnoo Blas

Unlike many road circuits of its ilk, Gnoo Blas is almost totally preserved in its original form, although the road surface is naturally considerably better than it was 50-odd years ago and the obligatory traffic islands blight the corners formerly known as Windsock and Speet’s. Located three kilometres south of the city of Orange, nowadays a thriving commercial centre of around 40,000 people, the circuit’s eastern extremities are bordered by the main rail line connecting Sydney with the west of the state. The area inside the northern end of the circuit, which encompasses the old pit area, and was originally an aerodrome, is now called Sir Jack Brabham Park. The local sporting car club holds a reunion here every year, and the entire lap has been thoughtfully signposted showing the original corner names. A noticeboard briefly describing the circuit’s history stands opposite the original start/finish line.

Leaving the old starting grid the road crests a slight rise before sweeping downhill through what would have been a quick left hand curve before it’s time to clamp on the anchors for Mrs Mutton’s Corner – a narrow right angle bend. This is followed by two crests, the second of which contains a very fast right curve (Connaghan’s Corner) leading downhill over a small bridge. This section, known as The Sweep, was the most challenging part of the course, and the only real bends apart from the squared-off corners common to public road circuits. After the Sweep it’s a long uphill climb before braking hard for what was Brandy Corner. This part of the track has changed from the original layout – a new section of highway bypasses what was a four-way intersection. The old road, with its quaint white-posted bridge, is still there, although now partially reclaimed by nature. Hospital Straight (which was renamed Total Straight after the French oil company paid £3,000 in 1958 to upgrade safety facilities required to meet the NSW Speedways Act) begins with a long right curve past the hospital and a golf course and finishes 2 kilometres later at the realigned former Windsock corner. The original corner was about 30 metres further on; a 110-degree hard right, while the new corner is a more relaxed, double right . A short squirt leads you to Speet’s Bend and back to the start/finish area.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook 2007 • Photo credits: Dennis Gregory, Laurie Fox, Charles Rice, Keith Conley