From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 85 – first published in 2020.

Words and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

It’s easy to dismiss the CL72 (and its bigger-engined brother the CL77), as “just a CB72 with high pipes”. Not so. The CB72 was created to cash in on the new-for-Americans awareness of motocross, which of course had been around for decades in Europe and elsewhere, including Australasia. And while there had been thinly disguised motocrossers, fitted with rudimentary lighting and slight concessions to comfort such as the two strokes from Jawa/CZ, Montesa, Zundapp, Greeves and four strokes from Matchless and even Triumph, the ‘Street Scrambler’ concept was indeed a brand new genre in the early ‘sixties. The emphasis this time was firmly on ‘street’.

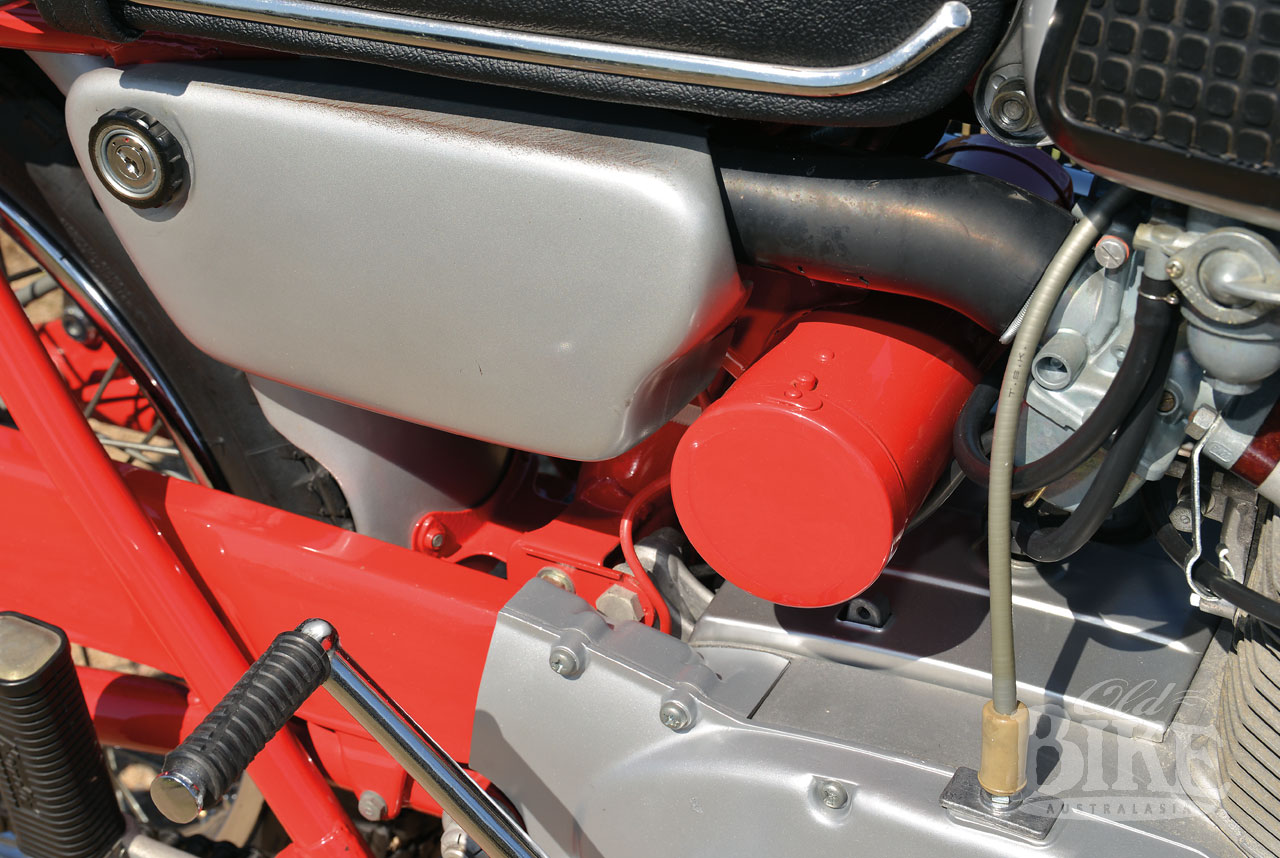

True, the basis for the CL was the CB72 engine, with its 180-degree crank and unit 4-speed gearbox, but this was housed in a completely new, semi cradle, all welded tubular steel frame, with 19-inch wheels shod with Trials Universal tyres. This new frame involved concessions, with the single front down tube fitting as it did very closely to the inclined cylinders and heads, and the front of the crankcase – where the starter motor usually resided. There was simply no option but to dispense with the push-button starting system (which also saved a worthwhile chunk of weight) in favour of the good old kick start system. This was easy and reliable in any case, but Honda went a step further by adding a longer kick starter with a revised internal ratio to get things spinning easier. Unlike the CB72, where the kick starter operated forwards, that on the CL worked in the traditional manner.

The weight saved from the elimination of the electric starter was sorely needed too, because the CL250 still tipped the scales at just below 150kg. A significant portion of this would have come from the exhaust system, but there was no getting away from the fact that the Honda – a twin cylinder, overhead camshaft four stroke, was always going to be porky compared to the two-stroke singles. Honda even went as far as to offer an optional (and expensive) aluminium-alloy fuel tank, original examples of which today command lofty prices. Suspending that weight fell to a set of new, longer travel front forks, with ‘heavy duty’ rear shock absorbers that retained the usual outer covers. A tubular, telescopic hydraulic-type steering damper was standard, attached via a small bracket to the right side of the cylinder head cover, and to the lower fork crown.

The afore-mentioned wheels sported unique steel rims, with raised shoulders that resembled the traditional alloy rims from Dunlop and Borrani. No big twin leading shoe brakes either; the hubs were smaller in diameter with single leading shoe operation front and rear. The 19-inch rims and fat tyres added ground clearance, but just in case any gibbers raised their ugly heads, there was a steel ‘bash plate’ bolted to the lower section of the frame where the front down tube joined the cradle section. Further fitments designed to biff stuff out of the way included the spring-loaded folding footrests for the rider. Those footrests also eschewed the usual rubbers in favour of plain steel, with little knobs on the foot area for extra traction.

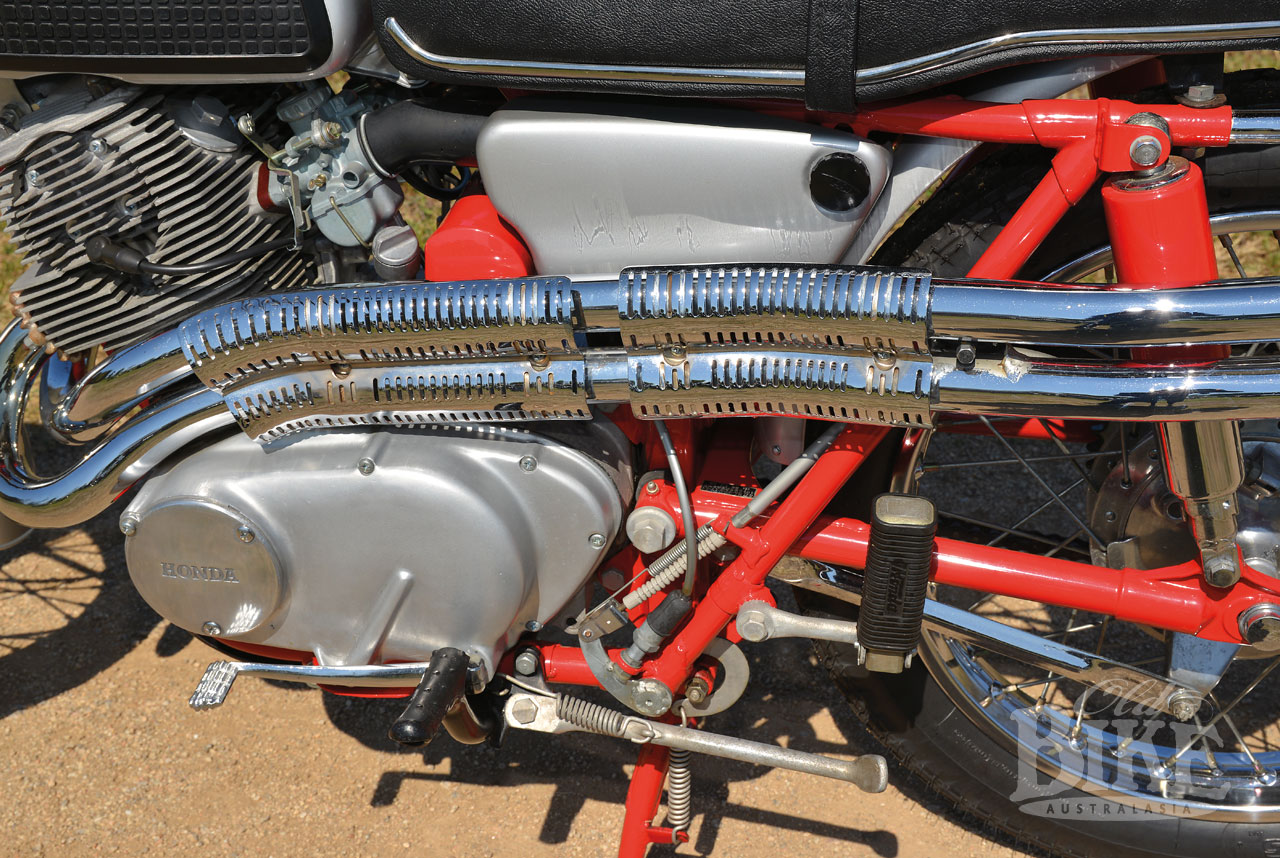

The crowning glory, and the visual signature of the CL was the exhaust system; a blinding mass of chrome plated steel, with twin exhausts and mufflers running up the left side, the latter section sporting a lattice work of perforated steel panelling which formed the heat shield, which was no gimmick – it was sorely needed, especially should the rider decide to carry a pillion passenger, which wasn’t such a great idea anyway. Just in case, the dual seat was long and comfy, with a chromed steel grab rail, and passenger footrests were standard equipment.

Dual purpose?

Of course, just how much ‘scrambling’ was actually done on the CL is questionable, but some did try. In reality, the domain of the CL were the Californian boulevards, and perhaps the foothills of the surrounding territory, and this is where the CL came into its own. With its distinctive, blaring exhaust note, the Honda was perfectly at home here. The CL72 appeared in late 1962 and continued for the next four years, being latterly joined by a stretched version of 305cc that produced 28hp. This was achieved by the simple expedient of enlarging the bores from 54mm to 60mm, fitting a marginally softer camshaft, and larger-bore 26mm carburettors. In other words, the engine from the CB77, sold as the Super Hawk in USA. At the same time, Honda fitted the larger twin-leading shoe front and rear brakes from the CB77, laced to 19-inch rims.

Instrumentation was basic; just a large, circular speedometer/odometer, reading up to 140 km/h mounted inside the headlamp unit. There was no integral tacho as on the CB72. The ignition switch lurked behind the rider’s right leg, located in the rear section of the right hand air filter compartment. Switch for the head and tail light was located in the headlight shell too, along with a high beam warning light. Turn indicators were fitted according to the market, but generally not for the first two years of production. Officially, the CL72 was produced from 1962 to 1965, and during that period there were minor refinements, most visibly the exhaust system, which went from the twin pipes into a single muffler in the final year. Around this time, the export CL72 was produced with the 360-degree crank engine specification (known as the Type 2 and identified by the stamping on the camshaft end cap), which had previously been available only in Japan.

As part of the exercise to flog the concept of a Japanese ‘scrambler’ to the suspicious westerners, Honda enlisted the talents of Dave Ekins – brother of the man who performed the famous leap to freedom in the movie The Great Escape. The task was to take a standard CL72 (actually two CL72s, with the second machine ridden by Honda dealer Bill Roberson Jr.) from the Mexican border at Tijuama down to La Paz, almost 1000 miles away, through interminable sand, rocks and over severe mountains, in as short a time as possible. Just how ‘standard’ these bikes were is highly questionable, with legend holding that they were fitted with special frames made from light-gauge tubing and most brackets and ancillaries similarly getting the weight-loss treatment. Both riders departed the saddle several times, with Robinson’s biggest crash resulting in an engine failure, but Ekins did record an impressive time of 39 hours 56 minutes for the journey – an achievement that Honda PR pumped up considerably. A major spin-off from the achievement was the creation of the Mexican 1000 race in 1967 over much the same course covered by Ekins and Robertson. This later became the Baja 1000 which endures to the present day.

End of the line

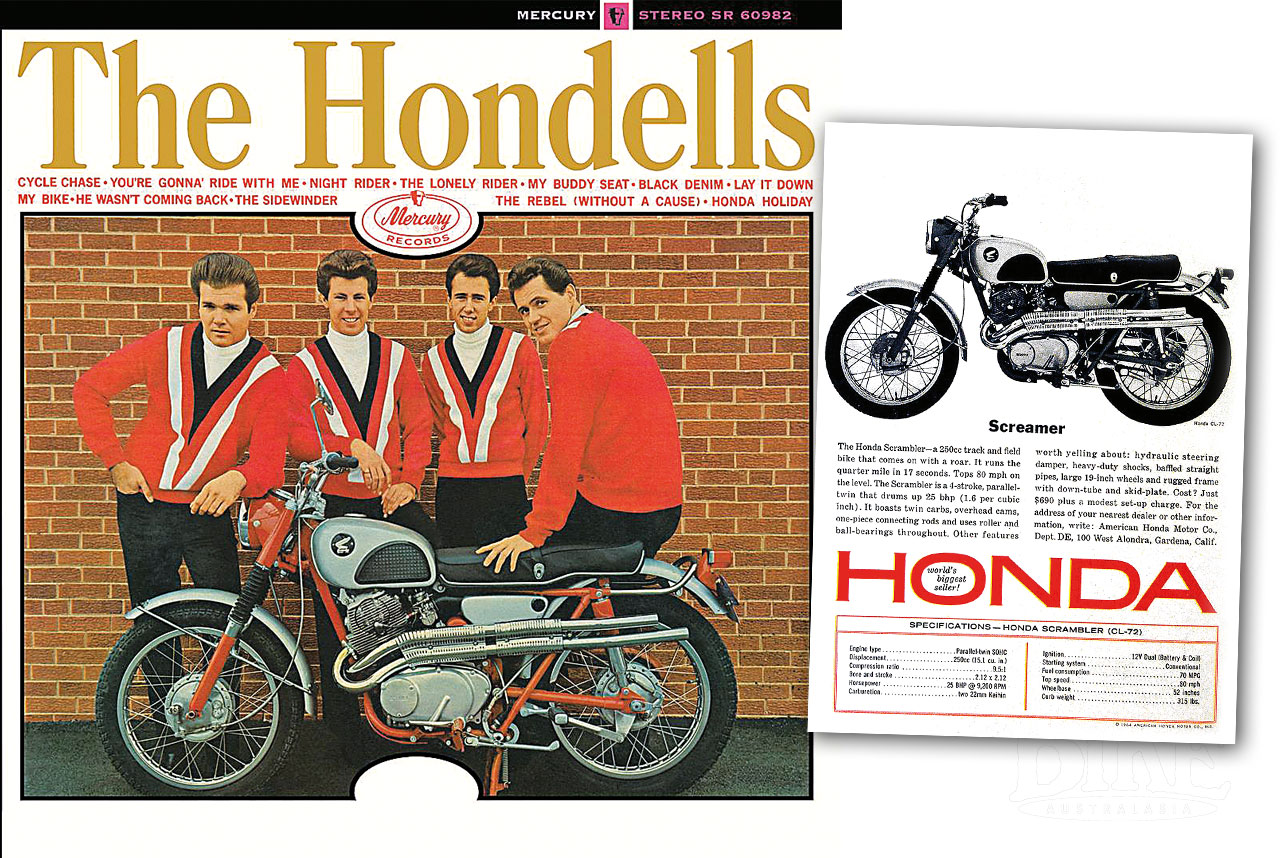

According to most sources, just on 90,000 CLs (including the 305 which went on until 1968) found homes during the production run, which was no mean achievement given that the competition went all out to produce their own ‘scramblers’ and the category became the hottest thing in the overall market. The CL72 even graced the cover of an album by the short-lived pop group The Hondells who recorded the 1964 hit single ‘Little Honda’.

The featured machine here was owned and restored by Honda marque specialist John Kelsey over a period of 25 years until sold in 2018 to Richard Steain to add to his Honda collection which includes a CB72, a CB450, a CB750 and several others. “John rebuilt the wheels with new genuine Honda 19-inch rims, but not the original shoulder type, which he still has with a view to having them re-chromed. The only other non-period correct item is the rear chain guard, which should have flutes in it. Apparently these are prone to cracking so John used a standard CB72 part.” One quirk of the CB72 is the oddly spaced gear ratios which produce a hefty gap between first and second, but Richard says because the overall gearing is lower on the CL72 this is not so noticeable.

By the time the CL77 ended its innings in 1968, the ‘Scrambler’ market had many players, including virtually all of the major Japanese manufacturers. Today, good examples of the CL72/77 – in fact the entire CL range which eventually stretched all the way to the 450cc DOHC twin – continually command superior prices to their CB counterparts. Parts for the CL72/77 are surprisingly abundant, with companies such as CMS in The Netherlands holding extensive stocks, which makes restoration not a particularly daunting task, and the result well worth the effort.

A different spin

Late in the production run, the CL72 was made available with the Type 2 engine, featuring a 360-degree crankshaft. Otherwise identical to the 180-degree model, the Type 2 version was said to rev a bit higher, at the expense of the mid-range torque. Many of these models were also fitted with turn indicators and the slip-on style muffler to mute the bark somewhat from the open twin pipes. Just such a machine was imported by Old Gold Motorcycles in Sydney in 2018 and is a highly original and unrestored example which retains the rare ‘shouldered’ DID steel rims and rocking-pedal gear lever.

Specifications: 1963 Honda CL72 Scrambler

Engine: Parallel twin, single overhead camshaft, two valves per cylinder, air cooled. 180-degree crankshaft.

Bore x stroke: 54mm x 54mm

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Power: 24hp @ 9,200 rpm.

Carburation: 2 x 22mm Keihin

Ignition: 12 volt battery and twin coils

Starting system: Kick only

Brakes: 8 inch SLS front and rear

Wheelbase: 1346 mm

Seat height: 800 mm

Top speed: 128 km/h

Weight (wet): 149 kg