What started as a Gold Star BSA and evolved to a Matchless G50-engined Norton, eventually became the 4-valve Henderson G50 – a mighty quick single.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Bill Forsyth, Dick Darby, Gary Reid, Bob Toombs, OBA archives.

If there were to be a Hall of Fame for racing motorcycles, a sort of two-wheeled Valhalla, you would likely find inhabitants such as Dick Mann’s Daytona-winning Honda CR750, or Mike Hailwood’s victorious NCR Ducati from the 1978 Isle of Man TT, or even Jeff Smith’s titanium-frame works BSA scrambler.

The machine that is arguably one of Australia’s most famous racing motorcycles has no such thoroughbred pedigree. It started life as a Gold Star BSA and underwent a transformation that left not one of its original components still fitted, but in the ensuing decade or so what emerged as the Henderson Matchless carved a unique place in the history of Australian road racing. In fact, the Henderson Matchless is not one, but two separate machines – the products of evolution and experimentation that went on for more than a decade.

The development of the machine paralleled the careers of two men who are now synonymous with the sport: Tony Henderson and Ron Toombs. Tony began his association with motorcycle racing as a keen clubman in the late ‘fifties and abandoned any on-track aspirations soon after to pursue his true calling as a gifted tuner, or to use the modern parlance, development race engineer.

Toombs on the other hand was a building foreman who combined the know-how of his trade with a sound mechanical knowledge, as well as a road racing talent that grew greater with every year. Ron was no instant success; in fact his most successful years were reached well past the stage when most modern-day racers have hung up their carbon-fibre back protectors.

The Henderson Matchless saga also involved at some stage the talents of many of the legendary engineers of the Australian ‘do-it-yourself’ style of racing development. As an apprentice fitter and turner with the Sydney Railways workshops, Tony had little spare cash, but managed to acquire a well-raced 500cc Gold Star BSA in 1959. He intended to convert the bike back to original trim and use it as a sporty road-burner, but one of his first outings was at the Arcadia dirt track north west of Sydney. The state abounded with such venues at the time, there being just one tar-sealed circuit within reach of Sydney that held regular meetings, at Mount Druitt. The only other venue was the once-a-year Mount Panorama at Bathurst. Arcadia was a fairly rudimentary dirt track that had been built by members of the Eastern Suburbs MCC on land donated to the club.

It was at Arcadia that Henderson first encountered Ron Toombs. The Henderson Goldie was a recalcitrant starter, particularly with Tony’s raw technique, and it was lucky for him that Toombs, who was campaigning his own 350 Gold Star at the time, took pity on the youngster and showed him the error of his ways. Tony was also quick to note that Toombs’ ability in the saddle far exceeded his own, so he offered Ron the 500 for the forthcoming Easter Bathurst meeting.

The results came instantly, with Toombs taking the 500 BSA to a win in the Senior Non-Expert event. But later in the programme, in the main 500cc race, the rear brake anchor broke just as Ron crested Skyline at the top of the mountain, sending Ron to hospital and the BSA back to the pits in a sorry state.

The birth of the brute

For the necessary rebuild, Tony sought assistance from the legendary engineer Charlie Ogden, and from Vintage Club founder Ray Corlett. Using Vincent flywheels, the rebuilt engine was fitted into a Dominator 99 frame with AJS 7R wheels. Here began the program of development that was to continue virtually non-stop for the next 10 years. By this time Toombs had acquired a 1961 7R AJS, which he campaigned with great success, riding the Henderson BSA/Norton in the Senior class. However despite Toombs’ skill, and the addition of a close-ratio AMC gearbox, the pushrod BSA was no match for the Manx Nortons in the Senior class.

By this time it was the early ‘sixties, and as any fan will recall, the era of Kel Carruthers. With his ex-Tom Phillis Honda 250-4 and a super-quick 500 Manx Norton, Kel was utterly dominant until his departure for Europe for the 1966 season. In a bid to challenge for Senior class honours, Henderson depleted his finances by £150 to purchase a 1961 Matchless G50 engine from English entrant and dealer Geoff Monty to replace the BSA unit. The motor was delivered with cracked crankcases, and a replacement set from UK arrived with a hole in the front where the cod rod had put a leg out of bed. These were welded at the de Havilland aircraft factory at Bankstown and re-machined. At the same time Henderson produced his own flywheels with a differentially-threaded crankpin – the system used on Moto Guzzi singles with 20-tpi on one side of the crankpin and 18 tpi on the other. “ I did them up with a three-pronged spanner and they never moved,” recalls Tony. Meanwhile, Ray Corlett, who worked at chemical giant ICI, got his hands on a billet of titanium, which Charlie Ogden machined to produce a connecting rod 5/8 inch shorter, and considerably lighter than the original. To complete the modifications, the G50 head was fitted with twin spark plugs.

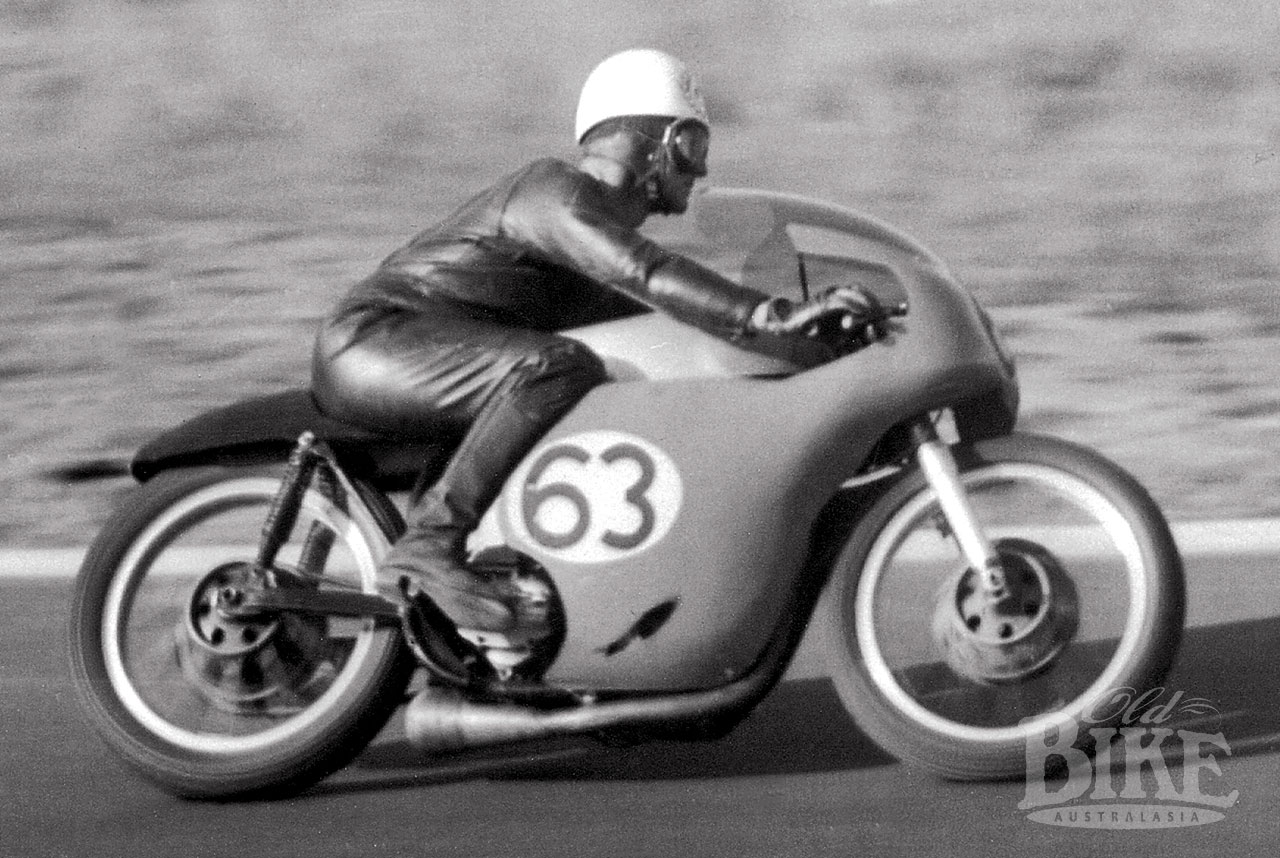

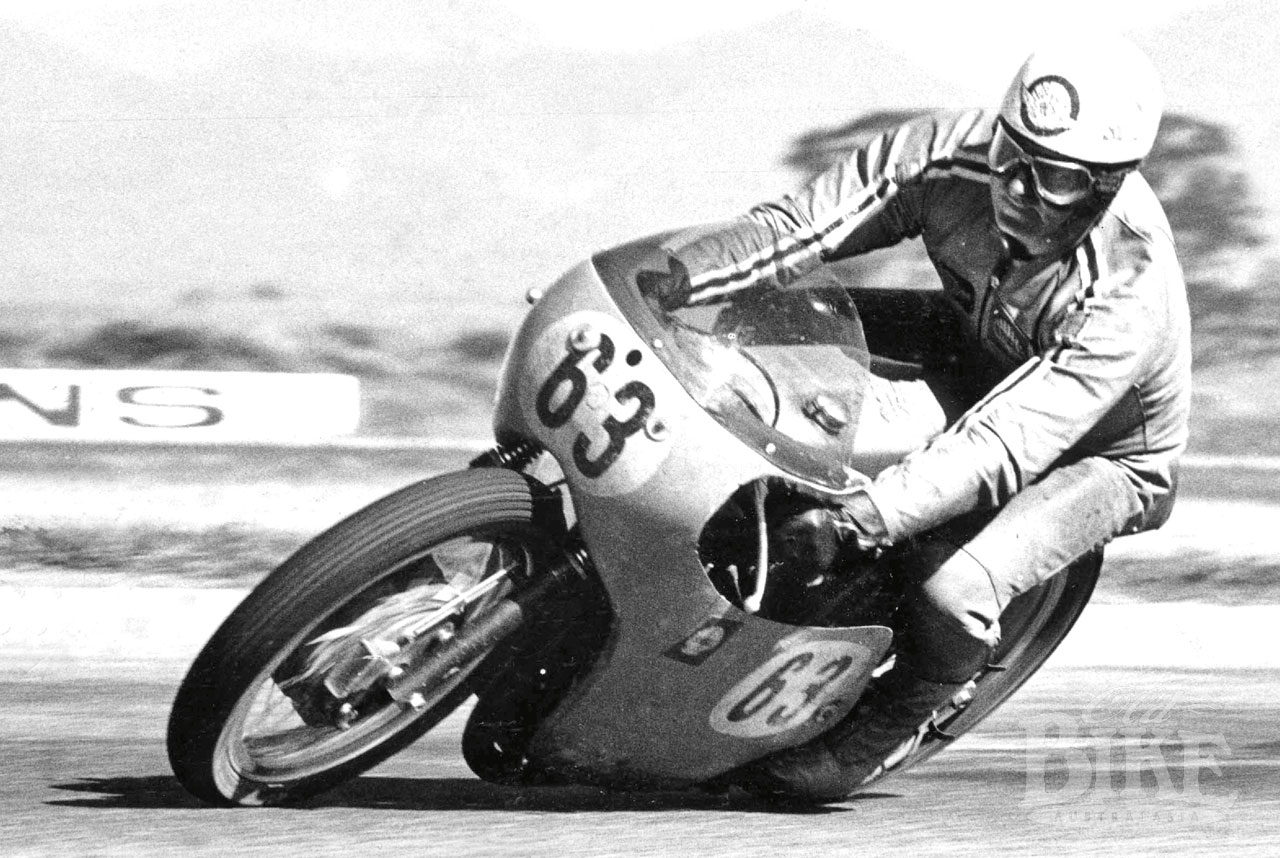

With the battered lime-green fairing from the Gold Star in place, the Henderson hybrid was no raving beauty, but an early outing in December 1964 resulted in Toombs equalling the Oran Park lap record. Results were scarce in 1965, with Toombs badly tearing a shoulder muscle early in the season, so the 500 was ridden occasionally by Len Atlee and Allen Burt. But at the Australian TT at Bathurst at Easter 1966, Toombs convincingly won the Senior TT, as well as the Unlimited title which was run concurrently. At the opening meeting of the new Surfers Paradise track in August, Ron and the Matchless were untouchable, taking the honours in all three major races.

The Victorian Grand Prix at Winton ushered in the 1967 season, and Toombs again took the G50 to the Senior title, repeating the feat one month later in the Victorian TT at Calder. Then at Bathurst’s Easter meet he scored his second-consecutive 500cc victory with veteran GP campaigner Jack Ahearn in second place on a very trick Lyster-framed Manx Norton. The year’s premier event, the Australian TT, was allocated to the Mallala circuit in South Australia, but after the long haul overland from Sydney, the Matchless dropped a valve in practice and non-started.

The 1968 Australian Grand Prix at Bathurst is an event still talked about. Toombs disappeared into the distance to make it three Senior Bathurst wins in a row, and had the Unlimited GP shot to pieces as well until he fell on an oil spill at McPhillamy Park on the final lap. As he struggled to right the G50, second placed Bill Horsman stopped and waited for Ron to remount, still holding the lead! Bill reckons the race was morally Ron’s, but his sportsmanship almost backfired when his own Norton ran out of fuel on the last corner. To complete a remarkable series of events, Jack Ahearn, in third place, idled along behind Horsman until he had pushed over the line to claim the runner up spot! It wouldn’t happen today.

Time marches on

With the advent of the TD2 and TR2 Yamahas, Toombs was forced to join the two-stroke fray in 1969, but continued to campaign the Matchless whenever possible. At the Australian Grand Prix at Phillip Island, Ron defeated Kel Carruthers (back briefly from Europe) to win the Senior, although Kel turned the tables in the Unlimited. Henderson and his friends also maintained the development schedule to keep the machine competitive with the two strokes. With the engine running on alcohol, generating sufficient temperature was often a problem, so Henderson cut most of the finning from the cylinder head and produced a cast-iron barrel. A six-speed Shaftleitner gearbox was procured, but discarded because the engine would not stay in its powerband. Instead, Henderson modified the four speed AMC box with half a tooth higher and lower on the original first gear base circles.

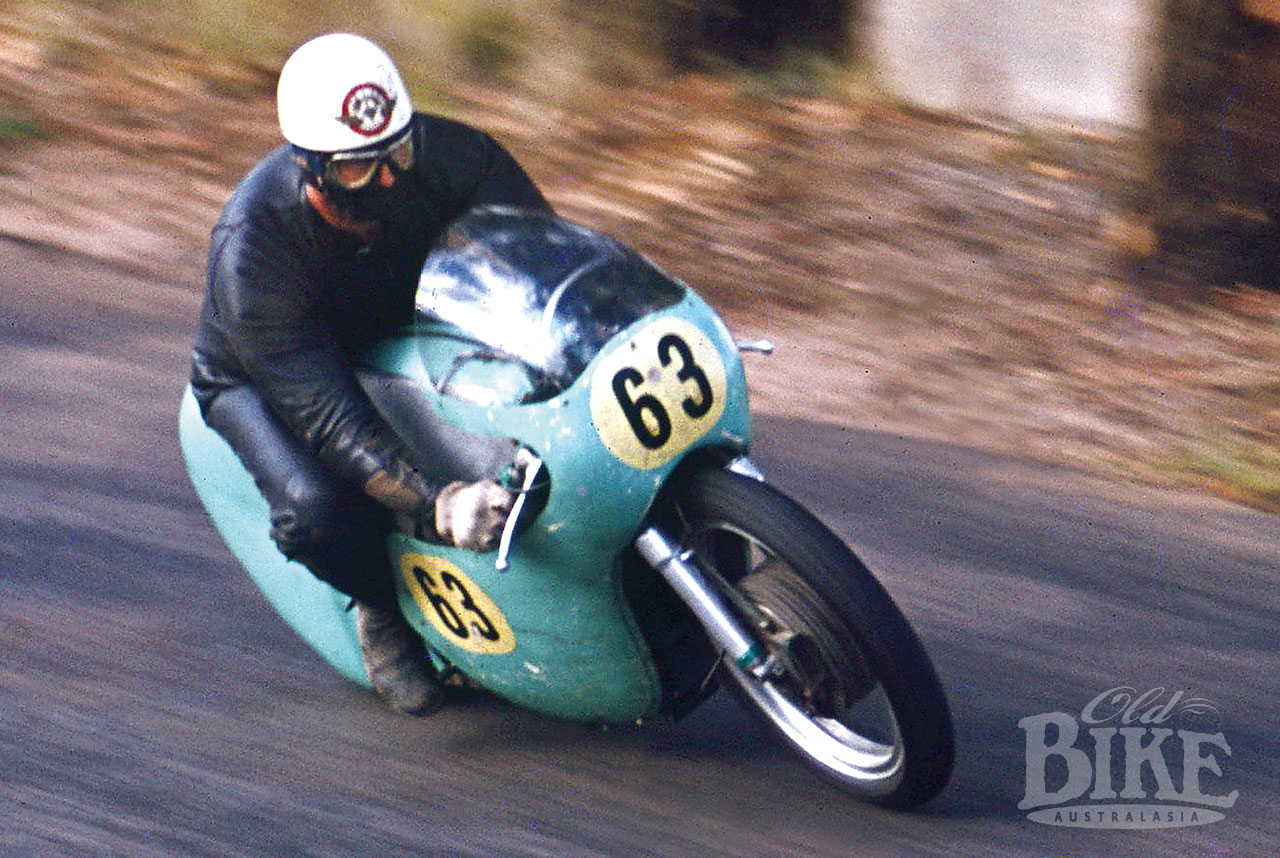

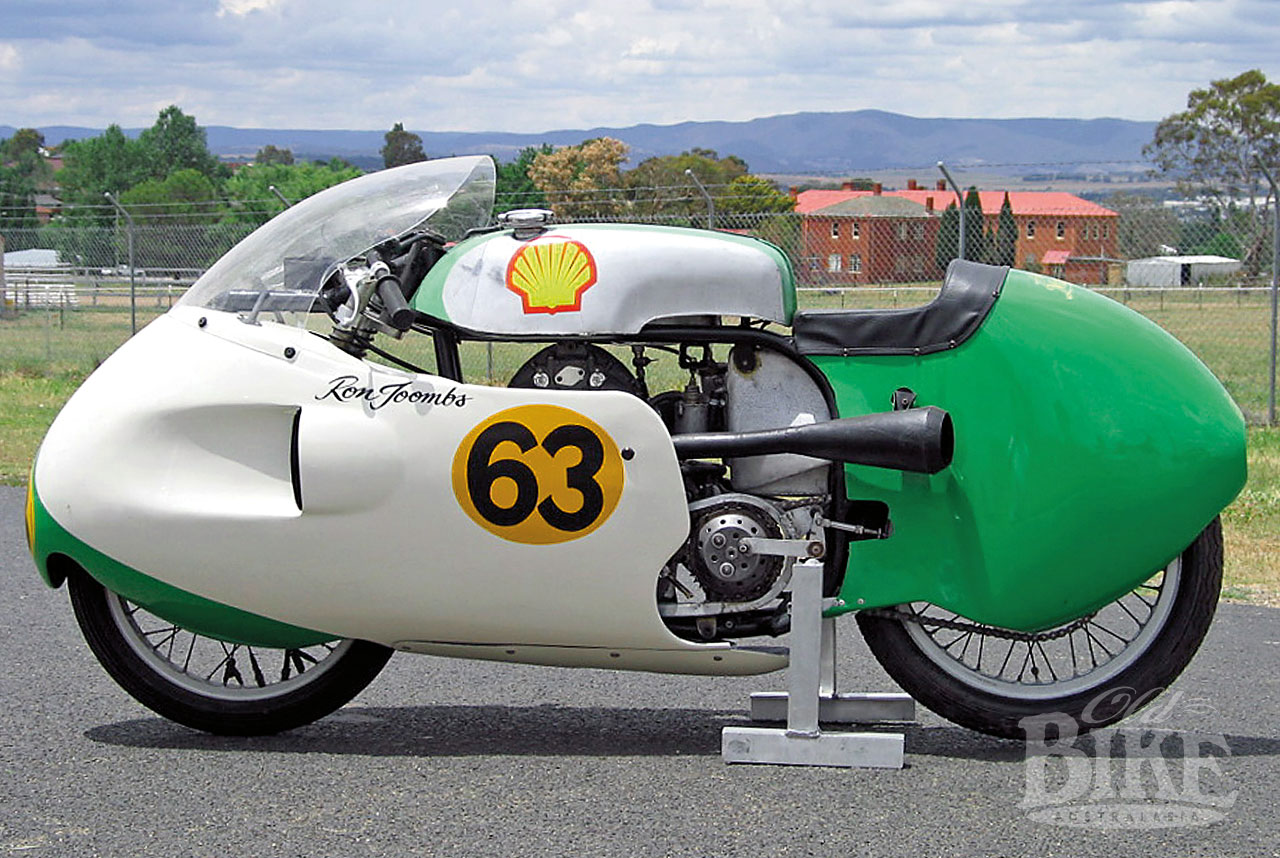

Next, a super-lightweight full cradle frame was fabricated by Malcolm Sullivan and welded by Bob Brittan, who made his name constructing the successful Renmax racing cars – copies of early Brabhams. Henderson fabricated a box-section stainless steel swinging arm from 18-gauge material and also cast his own magnesium fork sliders. Fuel and oil tanks were the work of Nooge Smith, who had made copies of the British Beasley frames (notably for Sid Willis) in the ‘fifties. Initially an Airhart front disc was fitted, but this was found to be inefficient, as well as making the front end far too light. There was no question of returning to the old 7R brake, so Tony acquired a set of unfinished castings made by Bob Kusel for a double-sided 8-inch front stopper. With just two weeks to the vital Easter Bathurst meeting, Henderson machined the magnesium castings and cast iron liners, made all the cams, levers and pivots, and laced the rim. The result not only restored the weight balance to keep the front end on the ground, but stopped perfectly. A small rear disc was machined and fitted with a modified single-piston calliper from a CB500 Honda.

But the crowning glory came with Henderson’s production of his own four-valve cylinder head. Ray Corlett had drawn up and cast a four-valve head with a 60-degree included valve angle. Just before machining was due to start, Henderson met engineer Merv Waggot, whose four-cylinder twin cam engines were powering winners in Australia’s premier open-wheeler car category. Waggot’s engine was based on the narrow valve angle Cosworth design with a 400cc cylinder capacity and had proven fast and reliable.

“I couldn’t ask Ray to draw up and cast another head using the Waggot design, so I machined one myself, as well as the cam box, from a solid block of aluminium” explained Tony. “We couldn’t get pistons either, so I machined one from solid as well – that took 40 hours.” The original Norton-framed G50 was parked, minus its gearbox, where it remained for years while development switched to the new creation. We were entered for the Phillip Island meeting on New Year’s Day, 1970 and I finished the (four valve) motor one morning just before then. Toombsie picked up the bike, which then fell out of his trailer on the way home! Nevertheless, the phone rang in the afternoon and it was Ron’s wife Mavis on the line. She held the phone up so I could hear the engine running in the background.”

Considering the total lack of testing, the creation worked well from the outset, the most serious problem being the primary chain, which stretched dramatically. “If you look at the chaincase, you can see the indentations from where the primary chain constantly threw off the rollers,” pointed out Tony many years later. “ We were running the same primary-size chain on the rear as well, so we ended up pre-stretching the chain on the rear before fitting it to the front.

After closely studying the flat-side Gardner item, Henderson made his own 1 3/4-inch carburettor. This proved difficult to tune until the needle diameter was increased to 5/32”, and after experiencing fuel feed problems the bowl was dispensed with and methanol fed directly to the metering unit.

Revvin’ heaven

From the start, the 4-valve engine revved to 9,200 but paid the price in terms of reliability. “I straightened the titanium con-rod at least three times. It dropped a valve at Oran Park once and wrecked just about everything but the head itself. That took about three months’ work to get it back together again,” says Tony.

Easter Bathurst in 1970 marked the last big win for the Henderson Matchless. For that year, the organisers dropped the Senior race and instead ran two Unlimited capacity races – the Bathurst Unlimited GP and the Bathurst Bi-Centenary GP. The top class saw Toombs pitted against the rapid but frisky new Kawasaki H1R racers, in the hands of Kenny Blake and Jack Ahearn, as well as a plethora of 350 Yamahas. In their first encounter, Blake bolted away to win from Ahearn and Toombs, who rode his 350 Yamaha in order to save the Matchless for the main ten-lapper. With a new outright lap record, Blake again cleared off to a huge lead until a broken chain brought him to a halt, leaving Ron and the Henderson Matchless to score a memorable and convincing win for big singles over Ahearn’s H1R and Kevin Cass on a 350 Yamaha.

Even with the writing on the wall, and a 350 Yamaha to contest all classes above 250, Toombs continued to thrash the Matchless around whenever possible. “When Agostini was here in 1971, Ron was chasing him hard in practice at Calder when the con-rod snapped and cut the crankcases in half,” recalls Tony. “(Former top sidecar racer and constructor) Peter Campbell welded them up but in the meantime I made a new set.”

A problem that had plagued the four-valve engine from the start was rough running at the top end of its rev-range. This was finally solved at one of the Henderson Matchless’ last appearances in Adelaide, where the diameter of the exhaust pipes was increased. Lo and behold, the unit now ran sweetly all the way to, and past if necessary, the 9,200 red line.

The last hurrah

By 1973, the Henderson Matchless was well and truly outgunned and destined for retirement, even though the weight had been pruned to just 240 pounds (109kg). Ron crashed the G50 comprehensively at Amaroo Park when the rear brake failed, and it looked like the old warhorse had fought its last battle. Toombs had accepted the role of lead rider for the fledgling Team Kawasaki Australia, run by Neville Doyle, and was successfully campaigning an H2R 750.

Around this time, English grass track supremo Don Godden was on a tour of Australia when he heard of the existence of the 64 horsepower Henderson G50. After some discussion, Tony agreed to bring the motor to Europe. Fitted into one of Godden’s frames, the unit was taken to Rastede in Germany, where the immense power snapped the rear chain adjusters in its first run. With this area beefed up, the Godden G50 went to the World Long Track final which was held on a trotting track in Oslo. In practice the magneto shaft sheared and was hastily repaired. Incessant rain turned the track into a quagmire, and again excess power was the problem, the machine digging huge holes whenever the throttle was opened. For the final, Godden returned to his JAP, but one week later took the Henderson to victory at Vilshofen in Bavaria.

Don Godden recalled, “Had we had a few more meetings to sort it out, I am sure we would have devastated everything else. It was unburstable. It had so much horsepower that it was years ahead of the standard Nortons and Matchlesses. One other problem was that Tony was in love! After years of thinking of nothing but developing his engine, now all he wanted to do was walk through flower gardens with Martha, the lovely American lady he had met! ”

Tony brought his engine back home, and it lay in one corner of the shed with the chassis in the other, until multiple Australian champion and Suzuka 8 Hour winner Tony Hatton convinced him to put it back together once more. Hatton took the completed machine to Phillip Island’s first Australian Grand Prix meeting in 1989 and put in several laps in a parade of former Australian international riders. Its years of solitude had resulted in the magneto malfunctioning, but it ran well enough to give a new generation of spectators a glimpse of what had been the most sensational motorcycle on Australian circuits.

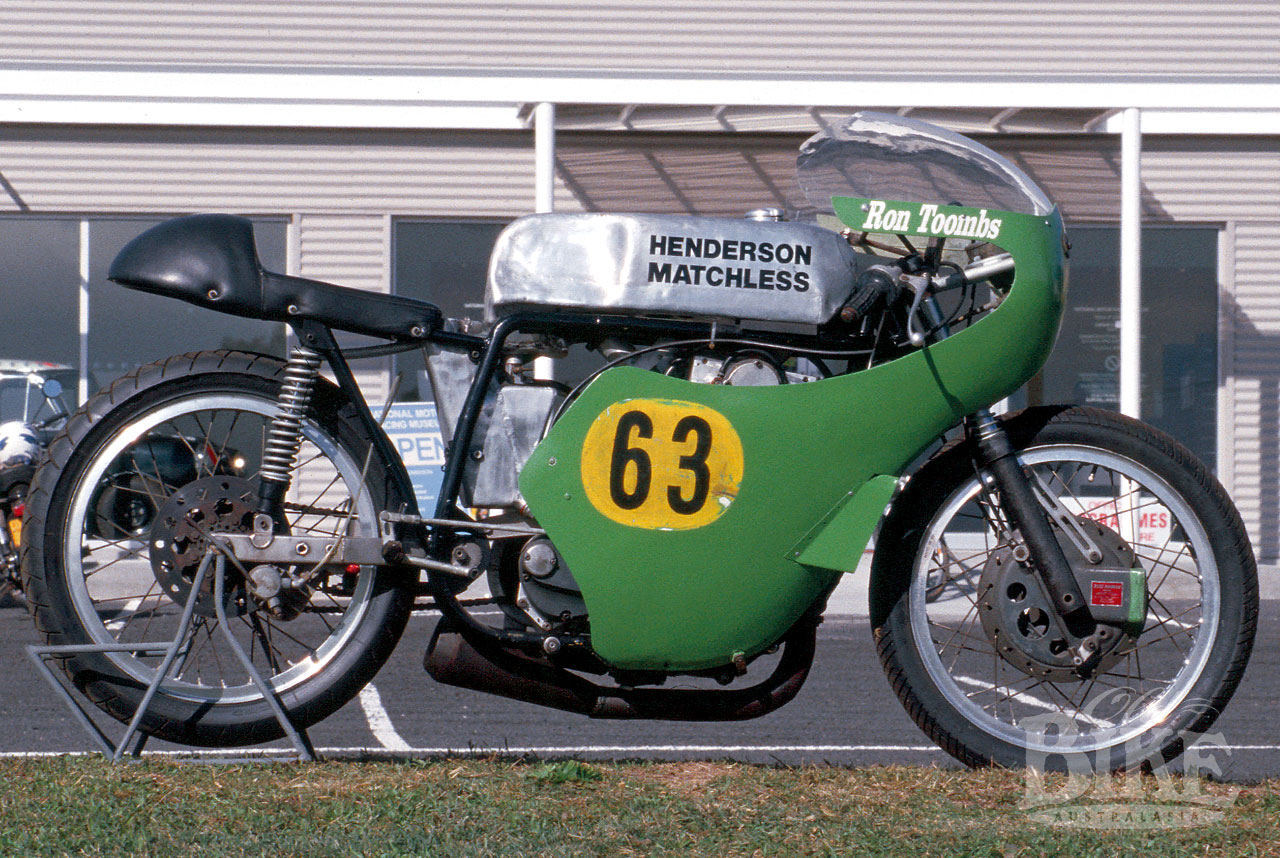

Thereafter, the famous old machine found a new and permanent place of retirement – as one of the feature exhibits at the National Motor Racing Museum adjacent to the final corner of the Mount Panorama circuit at Bathurst – scene of its greatest triumphs. And to prove that old soldiers never die, Peter Campbell collected the various components of the original 2-valve G50/Norton, and painstakingly restored the bike in the form that it won at Bathurst in 1967. That year, the Henderson Matchless was fitted with a dustbin fairing that had been outlawed in Europe but was still legal in Australia, as well as an NSU-style tail fairing that fully enclosed the rear wheel. After more than 35 years, both of the Henderson Matchless models were united once again.