From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 82 – first published in 2019.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Pete Slaughter and OBA archives.

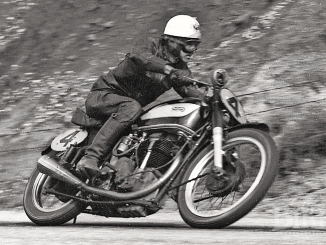

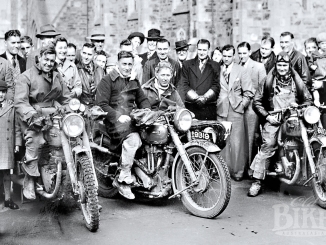

When the gritty Jeffrey Vincent Smith (later MBE) annexed the 1964 and 1965 500cc World Motocross Championships against formidable opposition, it was only natural that BSA would endeavour to cash in on that success.

After all, it had cost the company a great deal of money, but was the world ready for an overhead valve single that had been progressively enlarged to reach a ceiling of just 441cc? Indeed, with the booming US market in mind, big twins were what was in vogue, and not just BSA, but AJS/Matchless, Norton and Royal Enfield were doing their utmost to snatch a share of that market.

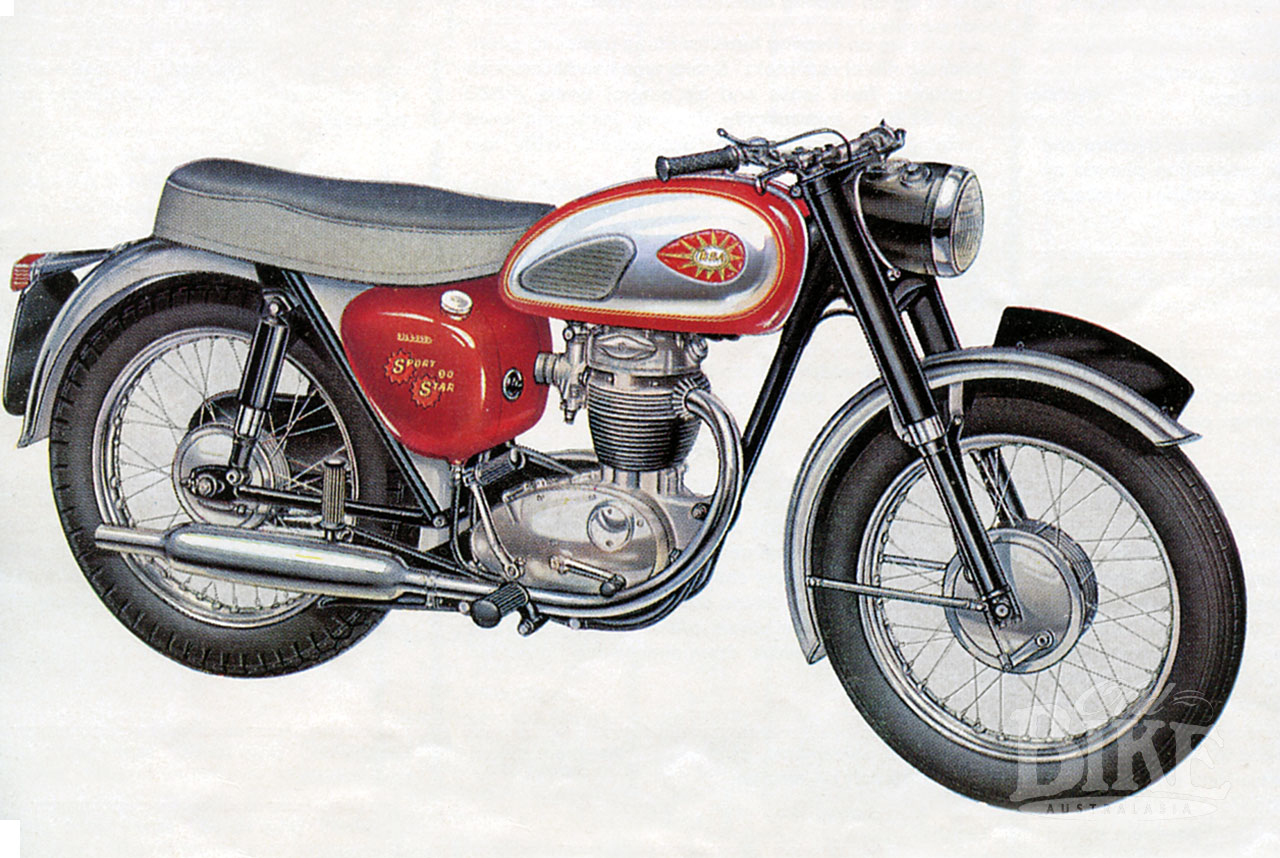

The 441 had grown from the 250cc C15, not a bad little bike at all, with engine dimensions of 67mm x 70mm; a well-mannered road bike that made a neat trials machine and a more than handy scrambler as well. Without the C15, BSA’s balance sheet would have looked fairly grim. Continuing the growth spurt, the C15 engine was punched out to 343cc by increasing the bore to 79mm to become the BSA B40 in 1961. Military versions of the B40 followed too, seeing service in the Australian army as well the British, where it remained in service until 1978. A 420cc Scrambler followed, fitted with an iron barrel, and finally, the 441, which Jeff Smith took onto the World Championship trail in 1964, the works machine fitted with a frame built by Reynold’s steel tubing guru Ken Sprayson. In honour of Smith’s victory-against-all-odds, the production versions (officially B44s) were marketed as the Victor Scrambler and Victor Enduro, which appeared for 1965 and were initially for export only.

Moving right along

Naturally there was considerable demand for a replica of Smith’s machine, which duly appeared as the Victor Grand Prix. The VGP featured oil-in-the frame to do away with the need (and weight) of an oil tank, a bespoke frame in Reynolds 531 tubing, a unique (unless you were a Vincent owner) 20 inch front wheel, and lots of alloy touches to keep the weight down to 116 kg. There was also a ‘cooking’ model, the Victor Enduro Trials with a conventional oil tank and heavier frame, and a considerably lower price tag. And using the basic package clothed in more conventional attire was the Victor Roadster (also known as the Shooting Star), which came on board for 1966, looking very much like the 250cc C15 and 350cc B40 Star and Sports Star models of the previous year with the exception of an angular, glass-fibre 2 gallon fuel tank, with the same material used for the oil tank cover. The same treatment was applied to the C15 to produce the BSA Barracuda. The B44 Roadster had compression lowered to 9.4:1 and breathed through an Amal Concentric with a 30mm choke size, good enough for 29 horsepower at 5,750 rpm. Electrics were supplied from a Lucas 100-watt alternator to a 12 volt battery, with coil ignition. The all-alloy engine used dimensions of 79mm x 90mm, and a two-way damped front fork with 5 ¼” ((133mm) of travel finally replaced the ancient single-damped BSA front end. Proven and effective Girlings shocks sat at the rear, with three-position pre-load adjustment.

But the Roadster was too cobby in its styling to win over the Yanks, who rather liked the look of the original Victor with its vivid yellow alloy tank and big fat red BSA stickers. However BSA decided against selling the Victor GP in USA, due mainly to its hefty price tag of at least $1400 which would have made it uncompetitive in the market that was increasingly dominated by 360cc scramblers from Husqvarna, CZ, Greeves and Maico. In 1967 BSA decided to remedy the situation by offering the US the Victor Special, which was basically what was sold in UK as the Victor Enduro Trials, fitted with seven-inch front brake, full road lighting, speedometer, horn, full chain guard and a street-legal muffler, and a single seat. In other words, a motorcycle that could be used in several forms of competition, and ridden to and from the event if necessary or desired. A compression plate under the cylinder could be removed to lift the compression ratio from 9.4:1 to 11.4:1, which gave a noticeable increase in power to 34 hp, but made it even more difficult to start. An Amal Monobloc of 1 5/32” was standard fitment. A 19 inch front wheel accompanied an 18 inch rear, both shod with Dunlop Sports scrambles tyres. BSA managed to get the Victor Special onto the US market with a price tag of $895, or $200 more than the twin cylinder Yamaha YR-1.

Never give up

The BSA big singles story didn’t finish with the B44 Victor. The tantalising prospect of three World Championships in a row caused BSA to abandon its normally frugal stance and opened fully the company coffers for 1966. A 494cc version was developed for the 1966 World Motocross Championship which featured some breakthrough thinking such as a rear disc brake sourced from Airheart in America – a disc front was also tried but abandoned in favour of a magnesium conical hub; the whole machine brimming with lightweight materials such as titanium, magnesium and aluminium producing an all-up weight of just 88kg. The most sensational item was the tubular titanium frame and swinging arm – even the handlebars were titanium. The frame, although 60% lighter than a steel version, was a disaster, constantly cracking and requiring highly specialised welding to repair – something that was just not available at many events. Despite many retirements, Jeff Smith finished third behind the two works 360cc CZs of Paul Friedrichs and Rolf Tiblin. One a heavily revised machine with a steel frame, Smith went one better the following year, again to Friedrichs. In 1968, Briton John Banks took over the BSA charge on the 494 and actually topped the standings after the final GP, but lost the title by one point on a count-back to that man Friedrichs. Banks was again runner up in 1969, this time to Bengt Aberg’s 400 Husqvarna. A severe knee injury forced Banks to miss the 1970 championship, but he was back with the works BSA for 1971, only to have BSA pull out of competition midway through the year, leaving him without a ride.

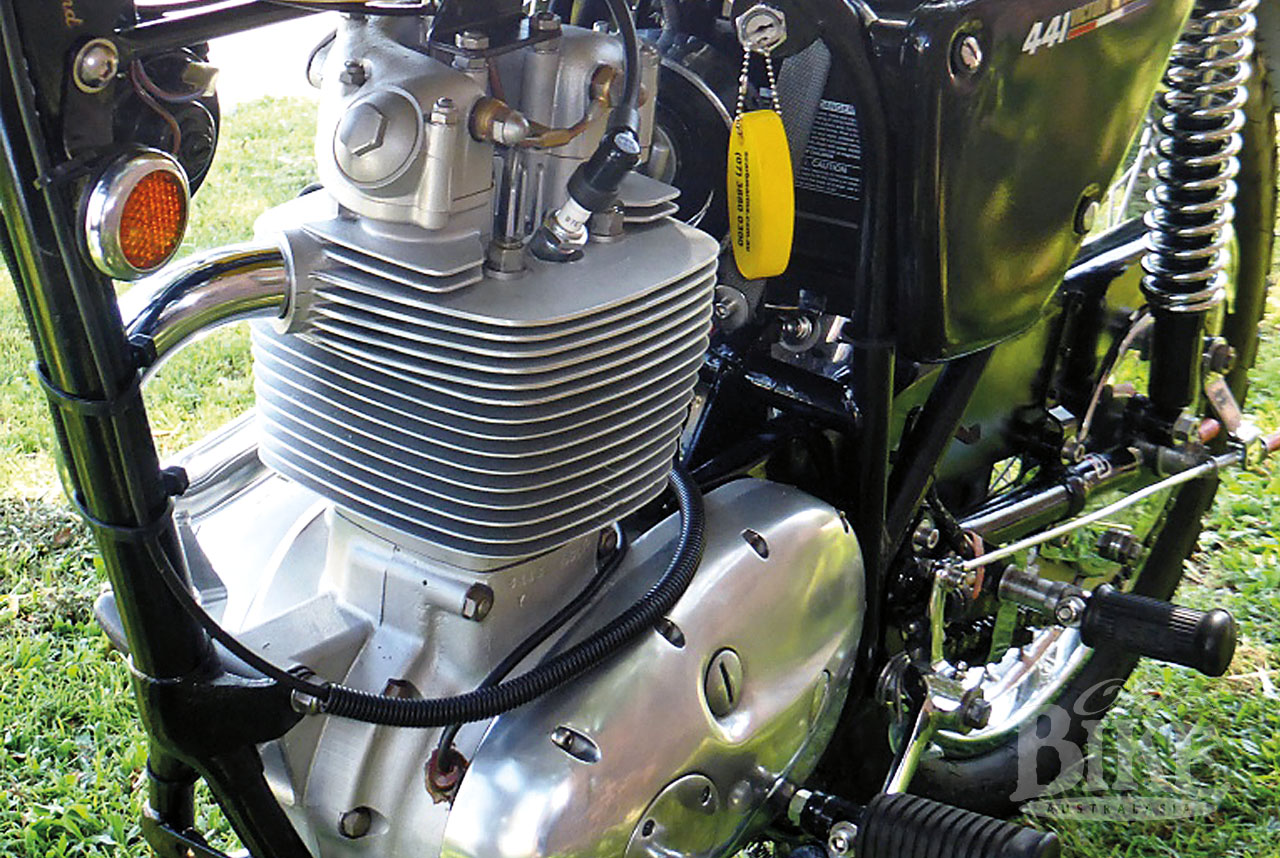

The Victor Special sold well enough in its primary market of the USA, but by 1969 was becoming a bit dated. It was time for a freshen up, and what transpired was the second incarnation of the Special, which wasn’t a lot different from the first with the exception of the engine. Visually, the Victor Special differed from the earlier motocross-based models by utilizing square finning for the light alloy head and barrel, giving it a slightly ‘Gold Star” look if your imagination stretched that far.

Prior to the release of the Victor Special, BSA’s works motocross effort, spearheaded by John Banks, found a way to get the engine out to a full 499cc, and ‘Big John’ put in a gutsy effort to finish runner up in both the 1968 and 1969 500cc World titles. That engine became the power plant for the last of the BSA singles; the B50 which appeared in 1971 in Trials, Scramblers and road form. The legacy of the works singles lived on in consumer terms with the B50, which by 1971 had grown into a full 500 (499cc) with bore and strike dimensions of 84mm x 90mm. It was marketed as the 500 Victor, and, to the horror of purists as the Gold Star 500 SS, which sported a twin-leading shoe front brake. There was also a pure racing version, the Victor 500 MX, with oil-containing frame and other lightweight parts that got the dry weight down to a claimed 109kg. The B50 staggered on until 1973.

Something Special

With 30 horsepower at 6,000 rpm, the new Victor Special was theoretically capable of just on the magic ‘ton’, but it was a brave man who took it that far. Using what was essentially still a 250cc bottom end, with light flywheels, the new Victor brought a fresh meaning to shake, rattle and roll. Still, the Victor Special was light (145kg) and nimble, and could still tackle a spot of off-road work if called upon to do so.

BSA now offered the Special to markets other than UK and USA, including Australia and New Zealand, where it sold in modest numbers. With its visual links to Smithy’s world title winners and the unmistakable yellow alloy fuel tank with its big red BSA stickers, it was a brutally handsome devil, to be sure, and if you disregarded the denture-shattering vibration, not a bad road bike. Along with the double-damped front forks came a mid-level exhaust pipe with a silencer fitted with a perforated heat shield, painfully close to the right leg of any pillion passenger, which could now be carried thanks to a dual seat that was firm but did have a nice little lip on the rear and a chrome grab rail. To make life slightly easier for the components inside the speedo, the single instrument was mounted in a substantial rubber holder, situated above the rather petite headlight unit.

Despite the good looks and good intentions, the Victor Special had its faults, which became glaringly apparent when the motorcycle was pressed into everyday service and subjected to constant highway use. A blow-up was no longer a figurative term; this was the real thing. The C15-derived transmission suffered badly with the increase in horsepower, and broken shafts and cogs were not uncommon. The clutch also slipped under hard use. If there were any amount of road use involved, fitting a countershaft sprocket of one or preferably two teeth larger was a shrewd move in order to keep the revs down. BSA also got involved in the Lucas Energy Transfer system, which made it (theoretically) possible to operate the machine without a battery, or with a flat one. Reality wasn’t quite so kind.

Pete Slaughter’s restoration

The Australian-delivered 1968 BSA Victor Special featured here (engine and frame number B44B 1636 VS) had been stored in a shed in Queensland for 30 years when Pete Slaughter obtained it in 2012. The first owner was Noel Brown, from 1969 to 2012. It had been last registered in March 1974. As found, it was in dirt bike form, having been used in the Hughenden district for scrambles races, although it was original and substantially complete. Given that it was only six years old when it was parked up, the BSA had been through the mills, having shed its road gear and been subjected to a life of rough riding.

Given the square finning for the cylinder and head, it would have originally been a Victor Special, not a GP, which had the smaller round finning like the C15 from which it was derived. The restoration began with a complete strip down and one of the first items to be tackled was the petrol tank, which was panel beaten, polished and repainted to bring it back to the iconic yellow finish. The engine was completely stripped cleaned by Aqua Blast Shop and fitted with a Micro-MKIV Electronic Ignition unit -thereby eliminating one of the original Victor’s greatest bugbears. A new Amal Concentric 930 carb with circular air filter was fitted, and the whole bike was rewired with a new loom.

The wheels were dismantled and fitted with polished stainless steel rims and spokes, and Dunlop K70 tyres which matched the period. Peter found an original tool roll with BSA factory spanners and badge. The tatty levers and handlebars, with the various well-used controls, were scrapped and new original-spec items sourced, including hard-to-get-parts such as the reflectors mounted on the front down tubes.

Pete is quick to acknowledge the help he received from several sources during the course of the restoration, including Clyde Slaughter, Rick Blake, Aqua Blast Shop, Ash’s Wheels, Mike Reilly Classics and Neil Currie. By 2016, the Victor Special was ready for a roadworthiness certificate and Queensland classic registration.

Specifications: 1969 BSA Victor Special

Engine: Single cylinder OHV, air cooled.

Bore x stroke: 79mm x 90mm

Capacity: 441cc

Compression ratio: 9.4:1

Carb: Amal Concentric 30mm

Ignition: Battery and coil

Power: 28hp at 6,500 rpm

Gearbox: 4 speed

Frame: Tubular steel, semi cradle.

Forks: BSA telescopic

Rear suspension: Swinging arm with Girling shocks.

Brakes: Front: 8” Rear: 7”.

Tyres: Front: 3.25 x 19 Rear: 4.00 x 18

Seat height: 790mm

Wheelbase: 1346mm

Weight: 139kg

Price when new: $840 (NSW)