Story and photos Geoffrey Ellis

Fast and ferocious; the Bridgestone 350 GTR had few equals in terms of performance and build-quality.

Bridgestone’s 350 GTR was undoubtedly the finest of the 1960s mid-sized two-stroke motorcycles in both quality and innovation and as a testament it created one of motor-cycling’s greatest myths – that the big four Japanese motorcycle companies forced Bridgestone to stop manufacturing motorcycles. Even on the centre stand the 350 GTR looked fast with a racing styled petrol tank and kick-up at the rear of a long and very plush seat. Quality oozed from the metallic maroon paint, chrome and polished aluminium and innovation set it in a class of its own. Performance wise, there were few motorcycles capable of keeping pace both at the drag strip or the racing circuit. Magazine articles complemented the GTR as the most innovative motorcycle on the market, an exercise in craftsmanship and advanced design that was practical and usable. The Bridgestone GTR was special and indeed a fitting last model for a range of excellent motorcycles.

Bridgestone’s story is one that parallels Japanese business and government policies. Soichiro Ishibashi, the founder of Bridgestone, had exceptional business acumen for identifying opportunities. Born into middle class Japan, his parents owned a small but profitable clothing manufacturing company which he eventually owned. Looking for an opportunity to expand, he introduced Jika-Tabi manufacturing to the business. Jika-Tabi was common Japanese footwear consisting of a thick sock with a rubber sole. Producing these educated Ishibashi in rubber goods manufacture.

In the 1920’s the Japanese government rightly believed Japan was being exploited by foreign organisations. To combat this, they introduced high import tariffs to a point where it was impossible to import goods into Japan. They then offered lucrative incentives for 12 months using the guise of “research” to new local businesses to stimulate growth, the reason so many Japanese businesses started as research enterprises. This policy stopped supply of goods to Japan creating huge shortages which generated many opportunities for Japanese businesses. Ishibashi seized this opportunity in 1930 starting a “research” company manufacturing bicycle tyres and after the 12-month financial government incentive period the Bridgestone Tire Manufacturing Company was established in 1931. In Japanese, Ishibashi translates to “stone bridge” so reversing it gives Bridgestone. Other Japanese tyre manufacturers had technology agreements and joint ventures with British and USA tyre makers often using their brand name whereas Bridgestone did not. As a marketing strategy the use of a British sounding name gave the illusion of technical assistance and a quality product although their tyres were just copies of others.

Japanese tyres were first produced in 1917 by the Yokohama Cable Company under a joint arrangement with B F Goodrich and by 1929 had two large manufacturing sites. However, the market was such that Bridgestone expanded rapidly. As Japan geared up for war and especially when all industry was put under the control of the military, Ishibashi’s decision to produce tyres soon saw him the owner of three large manufacturing facilities producing a wide range of tyres. War was not unkind to Bridgestone who were also fortunate that at the end of hostilities only one factory had been damaged and with the exception of aircraft tyres Bridgestone was back in the tyre business although rubber was difficult to obtain.

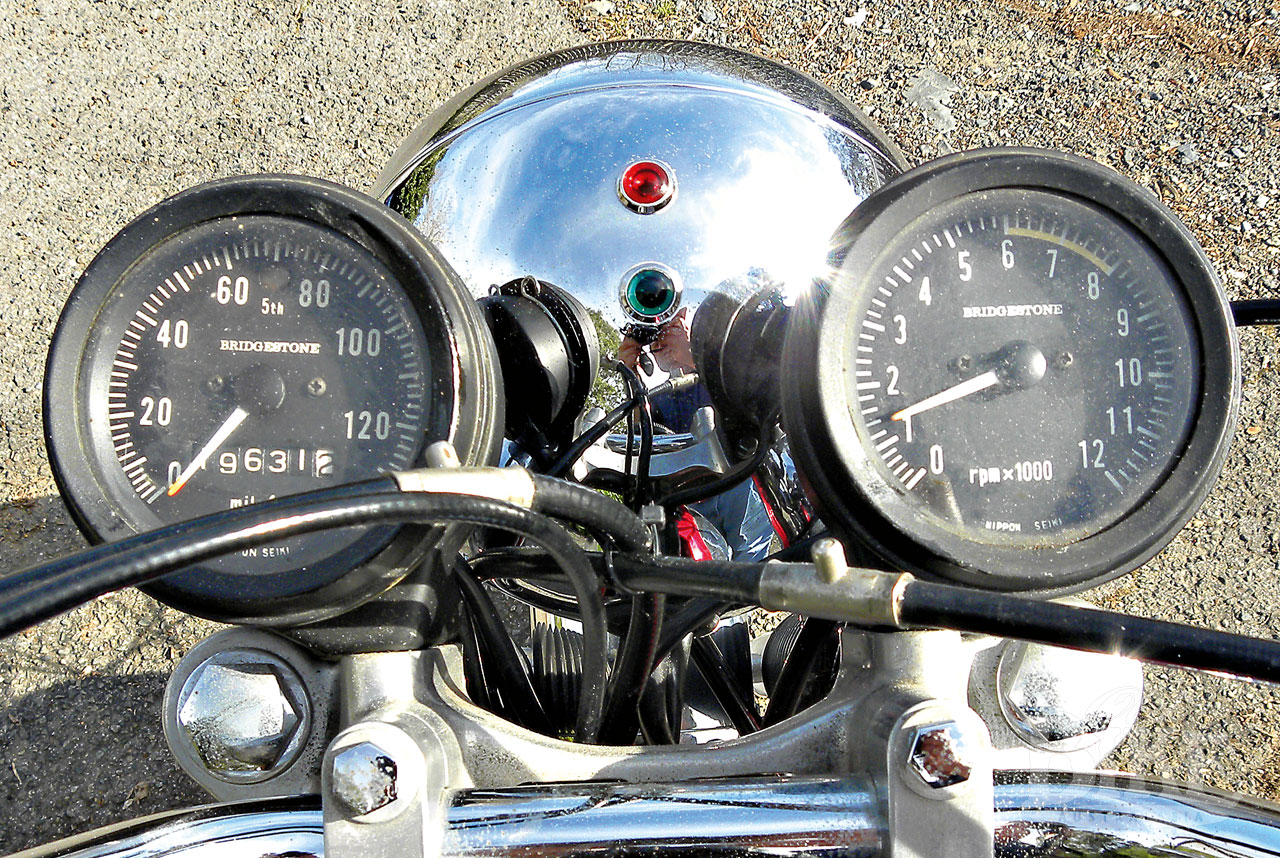

To take advantage of government incentives, Bridgestone manufactured bicycles. When the government incentives changed to suit motorised bicycles and small motorcycles, Bridgestone commenced producing a motorised bicycle in 1958 with engineering input from the car manufacturer Prince. The cursive “BS” logo was introduced on to the chain guard of these machines and became the tank badge logo on the motorcycle range with the 350 GTR being the exception as it was devoid of tank badges. Many small capacity motorcycles used two stroke single cylinder engines with rotary valve induction rather than piston port. In 1964, technology savvy Bridgestone released Japan’s first twin cylinder rotary valve induction two-stroke of 175cc establishing a new standard in technology and one that would be followed by the revolutionary 350 GTR in 1967. Kawasaki followed Bridgestone’s lead. One of the main factors making the Bridgestone GTR special was its exceptionally high build quality which also translated into reliability. In 1968 the Bridgestone organisation was awarded Japan’s highest and most prestigious manufacturing award being the Deming Award for Excellence in Quality Management, which was truly an outstanding achievement.

When released in 1967 the twin cylinder Bridgestone GTR was the quickest 350 on the market having a much lower quarter mile time than the competition and lower than many other makes with much larger engine capacities. This was due to the use of rotary valve induction allowing radical non symmetrical inlet port timing and space for a very effective rear scavenging port. The disadvantage was a higher manufacturing cost and a wider motor as the inlet valves and carburettors were located on the casings at each end of the crankshaft creating a problem as to where the alternator would be located. Innovation and Bridgestone motorcycles went together. Bridgestone solved the problem by being the first to locate the alternator behind the cylinders, driven by gears. At the time most rotary valves had a metal centre with a plastic or laminated disc moulded to it which quite often parted. To solve this problem Bridgestone developed a one piece plastic disc which was very reliable. Where other manufacturers either used an iron liner or plated the bore in the aluminium cylinders, Bridgestone developed cylinder coating by exploding chrome wire to coat the cylinder walls giving a far better and more reliable coating. Instead of the clutch being in oil like the competition it was air cooled. Bridgestone knew they built low stressed motors and all models were generally accompanied by a factory produced book showing owners how to extract more power. Many were tuned using these books and successfully used in competition.

A twin tube cradle frame housed a rubber-mounted 346cc twin cylinder two stroke engine with a claimed power of 40 bhp at 7,500, although the motor could be pushed to 8,500 rpm. In typical two stroke fashion there was little power under 4,000 rpm but once this was achieved the bike accelerated rapidly. A very high two stroke compression ratio of 9.3:1 was used. Ironically, when tested at the drag strip many articles complained of lack of grip from the Bridgestone manufactured rear tyre causing the bike to slide side-ways resulting in a longer elapsed time and not showing the GTRs full potential. Riders achieved 160 kph but the motor rapidly ran out of breath above this speed. As the GTR was fitted with 3.25 x 19 inch wheels front and rear, the tall seat height (838 mm) gave concern to some riders although it was a comfortable riding position. Cornering was good but could be improved by stiffening the soft suspension which did not like corners with uneven surfaces. The rear suspension units had an optional more upright mounting position using the seat mounting bolts for an alternate top mount. With a plush suspension and a heavier weight a very comfortable ride ensued.

At low speed the rotary valves created an unusual induction noise that seemed louder than the normal piston port induction. Braking was only barely acceptable as the twin leading shoe front brake was the same as that used on the 175cc twin but where it had been excellent on that model it was found to be wanting on the 350. Starting the motor was easy with one prod of the kick start lever and shifting gears was smooth. One aspect of the GTR that was universally questioned was the fact that neutral was placed below first gear, instead of between first and second. The frame and motor were designed with all brackets to allow the gear lever and brake pedal to be swapped to the other side. Bridgestone were the first to incorporate a sight glass for gearbox oil level. From its introduction until the end of 1969 only about 6,500 GTR’s were manufactured. The featured 350 GTR was built in December 1967 and restoration was relatively easy as many new parts are still available from the USA.

Bridgestone produced excellent motorcycles and when manufacturing ceased some-how one of motor-cycling’s greatest myths started that Bridgestone motorcycles were so good they were forced out of business by the other four Japanese manufacturers on the basis that the four would not fit Bridgestone tyres if motorcycle manufacture continued. Makes a good conspiracy theory but far from the truth as a number of factors came together which convinced the management of Bridgestone to cease motorcycle production. The part of the myth about the big four not using Bridgestone tyres omits the fact that at the time Yokohama supplied the majority of OEM tyres with Suzuki using their own tyre supplier, Inoue, for many models. Bridgestone had in fact decided to only produce a limited range of motorcycle tyres primarily for their own motorcycles. In 1963 Bridgestone acquired Fujikura Rubber, who were the OEM tyre supplier to Yamaha, and ceased production – forcing Yamaha to use Yokohama. As for being a threat sales-wise, for the total production of motorcycles of Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Bridgestone in 1968, 92% of the motorcycles produced were from Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki (the big three) with Kawasaki being 4.5% and Bridgestone 3.5%. Bridgestone could hardly be seen as a threat or even a significant producer. Whilst Bridgestone motorcycles may have been profitable it was a low financial return made worse by the deletion of government incentives and restructuring of the organisation in 1966.

The real reason to cease motorcycle manufacture came back to investment banks and return on investment. Even as the first 350 GTRs were being produced, the fate of the motorcycle division had been decided. Bridgestone had targeted Japan’s booming car production which had a far better future than motorcycles and had greatly increased tyre manufacturing with heavy investment in equipment and facilities. This returned good profits but created a large debt. Factory space was at a premium and the area of the factory producing motorcycles could be more effectively used to produce car tyres. In line with other manufacturers, Bridgestone could see that the USA’s anti-pollution requirements were heralding the end of the two-stroke engine but Bridgestone had no four stroke expertise and it would be expensive to obtain. Costs for technology, design and tooling for new models plus a new factory, all for extremely low profits in a difficult credit market, made the decision to cease motorcycle manufacture very easy. Far more money could be made from automotive tyres.

Although manufacture of Bridgestone motorcycles ceased for the rest of the world by the end 1969, the 350 GTR and the later high pipe GTO were still being produced and sold new to the USA up to 1972. The reason is believed to be that Bridgestone had an obligation of some form to its USA distributor Rockford Industries and financial obligations to both its investors (banks) and supplier base. A controlled build out was implemented so no party was financially disadvantaged. Adverts in the USA stated “Bridgestone motorcycles by Bridgestone Tire Company” until 1969 when they then stated “Bridgestone motorcycles by Rockford Industries”. Whilst there were stories of the 350 being produced in another country, the 350 was still made in Japan until its end by which time it had become very out-dated. Bridgestone motorcycle engineers were transferred to Kawasaki from 1970 remembering that some of these engineers had come from Tohatsu when it ceased motorcycle manufacture. There is a view with some support that another Japanese manufacturer may have produced the 1970 – 1972 Bridgestone 350s as part of a mutually beneficial deal.

Whilst the perception of Bridgestone tyres is different today, especially as they are now the control tyre for MotoGP, in the 1950-70 period Bridgestone was not innovative or active in the motorcycle tyre market producing a very limited range. Yokohama were the main motorcycle tyre supplier and produced Japan’s first GP racing tyres which were fitted as standard equipment to Yamaha’s TD1 and Kawasaki’s A1R production racers of the mid 1960s. A joint venture between Dunlop and Sumitomo Rubber starting in 1920 and still existing today, saw Japan’s first superbike tyre produced in 1968 and fitted to Kawasaki’s 500cc Mach 3 and developed further to be fitted to the 1968 Honda 750 four with most 1970s Japanese performance bikes fitted with Dunlop (Japan) tyres. Honda started using Bridgestone tyres in the 1970s mainly on its commuter models when Yokohama scaled back its low profit motorcycle tyre production.

History has justified Bridgestone’s decision to concentrate on tyres but maybe we should remember the 350 GTR and other Bridgestone motorcycles by the myth because they truly were magnificently engineered and built in the vintage Japanese motorcycle period.

The featured vintage Bridgestone 350 GTR has been authentically restored and is owned by Mick Bulman.

Bridgestone 350 GTR Specifications

Engine: twin cylinder two-stroke, rotary valve induction

Capacity: 345cc

Bore x stroke: 61mm x 59mm

Carburettors: 2 x 26mm Mikuni

Gearbox: 6 speed gearbox

Power: 40bhp @ 7,500 rpm (350 Yamaha 36bhp: 350 Kawasaki 40.5bhp)

Weight: 160.6 kg

Price when new: $689 (Yamaha $679; Kawasaki $715)