From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 92 – first published in 2021.

Story and photos: Jim Scaysbrook

For six years, from the inhospitable deserts of North Africa to the frozen lakes of Lapland, the Wehrmacht waged relentless war, with the BMW R75 a key component in the assault.

Domination on the race tracks with the fabulous supercharged Kompressor models was gratifying for BMW (and the Nazis) in the ‘thirties, but as the decade drew to a close, there were bigger and far more pressing issues than international sporting prestige to consider.

As the build up to WW2 intensified, both BMW and Zundapp were hard at work on designs for military use. The military contract called for motorcycles with capacities around 750cc, and Zundapp’s 751cc overhead valve KS750 filled the bill admirably. BMW’s R12, first produced in 1935, was a solid, side-valve 750 with a four-speed gearbox and shaft final drive, housed in a twin cradle, pressed steel frame. The front forks were oil-damped hydraulics with one-way damping, mated to a rigid rear end. The R12 was supplied for military use with a single carburettor replacing the original twin Amal carbs and from 1938 was available only to the military, in which form it developed 18hp at 3,400 rpm.

With the army demanding more and better motorcycles, BMW developed the R72, with an 800cc side-valve flat twin engine that was first seen in 1938. The heavy R12 frame was replaced with a tubular steel frame that was bolted together to facilitate easy removal of the engine. However the R71 was prone to overheating, particularly when ridden at speeds around walking pace, which was necessary in rugged terrain.

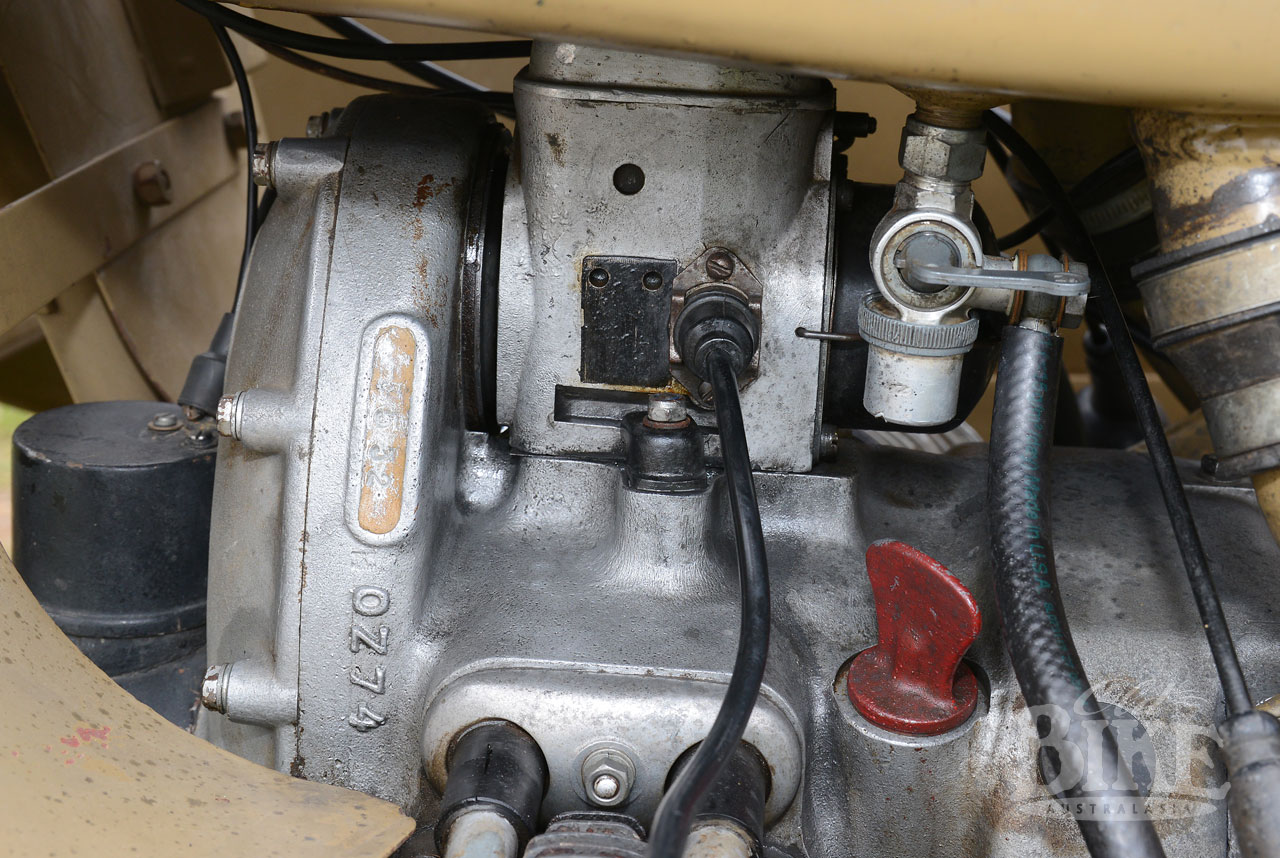

A new design was decreed necessary to counteract Zundapp and retain a share of the military contract. The result was the R75, an overhead valve engine in a sturdy, bolted-up tubular steel frame, which, unlike the R71, was designed from the outset as a motorcycle and sidecar combination. This basic design was subsequently to have a very long life, far removed from its army roots. Durability and minimal maintenance were key requirements, and to this end components such as the magneto, generator and camshafts were all gear, rather than chain-driven. The sidecar wheel was driven through a lockable differential and cross shaft.

The transmission was a complex affair with two-stage gearbox with four ratios for off-road use, and four road gears. In the highest ratio, a top speed of about 95km/h was possible. There were also two reverse gears. This allowed for speeds as low as 2 mph to be maintained, although at this pace the lack of cooling air flowing over the engine was a problem. With the likelihood that the machine would encounter river crossings, deep sand and mud, air for the twin Graetzin carburettors came through a felt air filter mounted in a cavity in the 24 litre petrol tank, the filter sitting underneath what looked remarkably like a German helmet. Long curved tubes then channelled the air to the carbs.

The R75 frame was a fairly conventional bolted-up wide cradle structure, with two-way damped telescopic forks at the front and a rigid rear end. Interchangeable 16-inch wheels and 250mm brakes carried 4.50 section studded tyres. The front brake was a cable-operated type with a drive for the speedo cable, while both the rear wheel and sidecar wheel had hydraulic brakes. The sidecar itself pivoted around a cross shaft in the footwell of the cabin, with a rigidly mounted wheel attached. Rider and pillion seats were individually sprung saddles, designed to support the weight of soldiers carrying full battle kit. In fact, the military requirement stipulated an ability to carry a 500kg payload, a figure that was probably rarely reached and which would tax tyre life severely. When fully loaded, the front fork also struggled to operate satisfactorily. Ready to roll without any human cargo, the military R75 with sidecar tipped the scales at around 420kg.

Until the R75 was considered suitable for volume production, the venerable R12 filled the void, but by early 1941 the new machine was ready to go. The completed machines were finished in different colours according to the intended destination; drab yellow for the desert models and grey for European deployment. Unfortunately by this stage BMW’s Munich factories were at full capacity building aircraft engines and components, so after a short production run it was decided to move the building of R75s to Eisenach, northwest of Frankfurt, which is today the centre of production for Opel cars.

The move to Eisenach resulted in a severe labour shortage, and poorly-trained workers, including some Russian prisoners of war, were brought in, resulting in major quality control issues that cost the company dearly to rectify. Raw materials were also scarce as the war dragged on, and BMW itself suffered major bombing damage at Eisenach as well as to its main factories in Munich. The R75 was also seen by the military authorities as being inferior to the Zundapp, and production numbers never reached expectations. The German army became increasingly keen on the Volkswagen Kübelwagen which was cheaper to produce and offered a greater load capacity.

The R75, despite its shortcomings, was nevertheless a solid and reliable unit which could cope with increasingly poor quality fuel. By the time the model was discontinued in late 1944, around 17,500 had been constructed; the final batches nearly all supplied to foreign armies. At the conclusion of the war, Eisenach became part of East Germany and small numbers of R75s were assembled from accumulated components by the occupying Russians.

Today, the Chinese produce a similar design to the R75, and Harley-Davidson also built an analogous shaft drive model, the XA.

A long way from the Eastern Front

The featured R75 belongs to Trevor Lever, a man who knows his BMWs (and Vincents). As could be expected, this machine has an interesting history, as Trevor relates. “To cut a long story short, an American Vietnam veteran, Kent Irwin, came to Australia for a holiday after the war, married an Australian girl and moved to Armidale. Later when he was working in Belgium, he spread the word around that he was looking for an outfit to buy and he was told that a local farmer had a couple of them. He was able to buy both, this one and a grey (Eastern Front) model. This one was part-restored around 1998 by a guy in Faulconbridge who was into military stuff and BMWs in particular.

“When Kent’s wife died about five years ago he moved back to The States. He took the grey one with him this one stayed with his son Royce Irwin, who now lives in Brisbane. Royce put it up for sale and I bought it. Funny thing, but I have full NSW registration papers for it, with a right hand sidecar, which I didn’t think was possible. Fortunately it was registered when I got it so I could keep the full rego going. That’s all changed now with historic rego; you can have sidecars on the right, left hand drive cars and so on. Adrian Vergison did some work on the bike for Kent Irwin years ago and the Graetzin carbs were always leaking, so he got a set of Chinese carbs which are pretty much identical and Adrian put them on for him, but he left the Graetzin tops on the bowls.

“To change the oil is a job and a half. To pull the sump off, it’s got a big sump guard underneath, with some 8mm and some 6mm bolts which are all bent, and the only way to get at them is to lay across the saddle and work upside down! Either that or you take the sidecar off, which is a huge job. The electrics are all working, the battery is being charged – I’ve just put one of the little 6 volt batteries inside the original case and it seems fine. Everything about the bike is massive and everything weighs a ton; built so they won’t break, like the steel pannier bags and their attachment brackets. Most of the blokes that use these put leather bags on to cut down the weight a bit.”

Unsurprisingly, few R75s survive. Most were destroyed in action, cannibalised for parts, or simply abandoned in retreat. Trevor’s in two minds as to whether to restore the R75, but is tending towards leaving it as is and concentrating on some small mechanical issues, such as the magneto that seeks to detach itself from its mountings, plus a few internal rattles from the timing case. The bike tends to run hot, an issue that also requires attention. Otherwise it’s a first kick starter and a comfortable ride, with a stack of storage space. The optional machine gun is not currently fitted.

Specifications: 1941 BMW R75

Engine: Horizontally-opposed twin, air cooled.

Bore x stroke: 78mm x 78mm

Capacity: 745cc

Compression ratio: 5.8:1

Power: 26hp at 4,000 rpm.

Carburation: 2 x Graetzin 24mm with remote bowls.

Ignition: Noris magneto

Frame: Tubular steel.

Wheelbase: 1444mm

Suspension: Front: telescopic fork with two-way damping.

Brakes: 250mm drum all round, rear and sidecar with hydraulic operation.

Tyres: 4.50 x 16 inch on interchangeable wheels.

Weight: 420kg with sidecar and fuel.

Fuel capacity: 24 litres