You would be hard-pressed to find anyone more comfortable with life than Steve Roberts, a man who has had a hand in more successful projects that you would think possible. For someone who arrived in New Zealand with his young wife with just seven shillings and six pence between them, Steve has done all right for himself, and made countless friends along the way.

In his native Britain, Steve was working for Aston Martin as a panel beater during the particularly grim (for the motor trade) early ‘sixties. “They couldn’t sell the cars. They were built, then just lined up to sit there – the last 25 (workers) in were the first 25 out, and I was number 25.” There was no work in Britain so Steve and his wife Pam decided on a cruise. “Just for a laugh, we thought we would come out to New Zealand, then take the long way home via Melbourne. Well, it (New Zealand) just clicked! We had no money so we couldn’t go out, but on our first day I got two jobs – one as a panel beater and one teaching panel beating at the new Polytechnic at Wellington. I was 23 years old and I was teaching 19 year olds, and they didn’t like it!”

Steve had a Norton Dominator 99 in England that he gave away when they left. “ I thought I would get another bike in NZ, but when I went into a shop and looked at the prices I just about died! I was stonkered – I couldn’t get a bike. One of the apprentices had an old Triumph engine – an alloy GP, so I bought it off him and built a frame around it as a motocrosser. The Rickman (Metisse) was the number one bike in those days, but I only had a few photographs so I used those to get the dimensions – and it worked! We called the bike a Spartan Triumph, and it got me into motocross in 1962/63. Then someone wanted to buy the bike and so I sold it and started building others with whatever motors I could get – JAPs, Nortons, Triumphs or whatever. They’re collecting them now you know!”

Building the Spartans allowed Steve to formulate many design features that would serve him well in later years. The fuel tank, seat, air box and rear mudguard were all moulded as a single unit in glass fibre. “One of these got stuck in the mould – I didn’t use the right separator – and I just couldn’t get it out. It was so incredibly strong it was impossible to bend. Years later, about 1983, I said to Dave Hiscock, ‘why don’t we build a plastic bike? Yachts are built of plastic. At the time we were racing the aluminium monocoque Suzuki. He was not convinced and I said, ‘Do you have an aluminium crash helmet or a plastic one? He thought about it and said, ‘OK, plastic sounds all right to me.’” It was the beginning of what is now termed the Plastic Fantastic – the GSR1000-engine TTF1 machine raced by Hiscock and Robert Holden, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Almost since the time he settled in New Zealand, Roberts has had a close relationship with Rod Coleman, whom he says ‘ has played a massive role in my life’. At the time, Coleman was the NZ Suzuki importer, his tireless promotion of the brand leading it to the undisputed number one sales position – something almost unique for Suzuki in world markets. Coleman supported many riders and dealers, notably Dick Lawton in Wellington. “Dick’s Suzukis were faster than the factory bikes,” Steve says, “and the factory knew it. I read in a recent interview with Mr Ito, the Suzuki race engineer, that this fact was a cause of much embarrassment to the factory. Geoff Perry rode the bikes and he was a star – a lovely guy and unquestionably a future world champion. “ When Sonny Soh crashed his works TR500 Suzuki in Malaysia and bent the frame, it was sent to New Zealand for Roberts’ attention. As well as straightening the frame, Steve made a jig and constructed an identical copy. “After that Rod decided to go the whole hog and we put in tapered steering head bearings, needle rollers for the swinging arm and made the arm itself out of square section tube. We made several frames with slightly different steering head angles.”

Two of the beneficiaries of Steve’s tube bending were Keith Turner and Geoff Perry. Aboard the Roberts-framed TR500, British-born Turner enjoyed a stellar season in 1971, finishing as runner up to the invincible Giacomo Agostini in the 500cc World Championship. Perry took his Roberts-TR500 (with special multi-port barrels developed by Dick Lawton) to Daytona in 1972 and rode it in the 200 mile race, despite being offered a works TR750 Suzuki, which he declined because of the known problems with tyres and chains coping with the power. After qualifying third behind Art Bauman and Jody Nicholas, young Geoff had the race in the bag when the 500 broke a chain on the final lap.

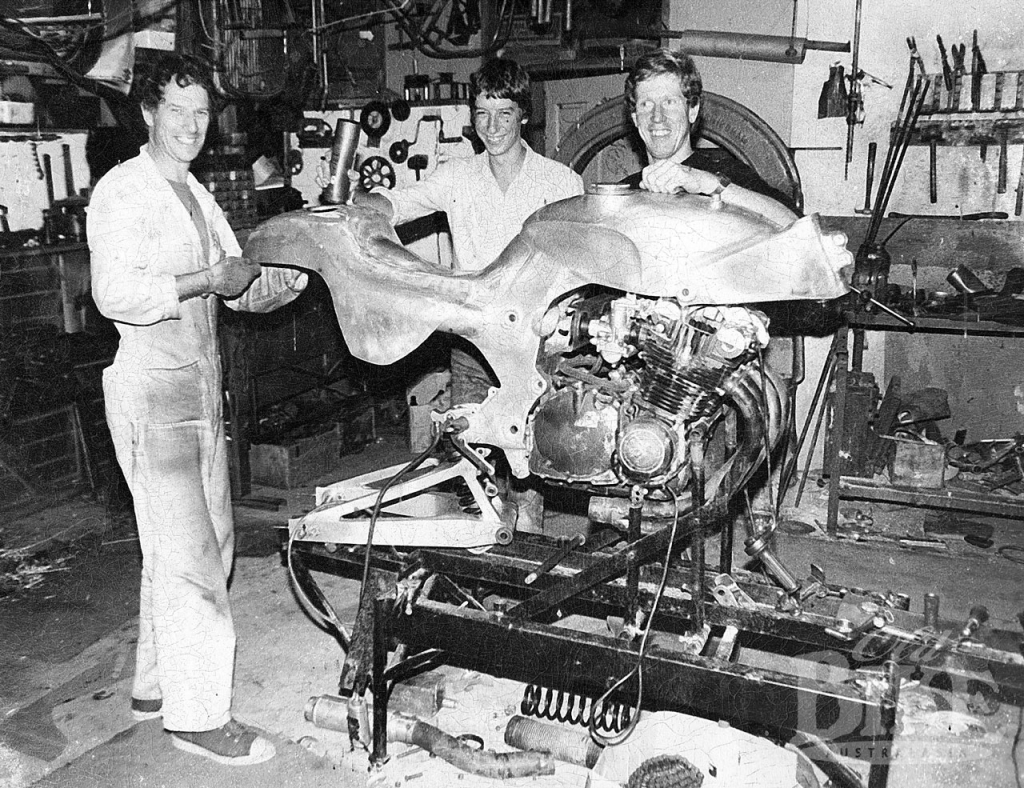

Altogether, Steve built around 20 steel tube frames for the TR500 engine, as well as similar chassis for the Suzuki GT380 triple (de-stroked from 54 mm to 50 mm to 350cc) and 250 twins, but around 1971, he decided on a different tact. “Keith Turner came back from Europe and he was very impressed with the aluminium monocoque frame built and raced by Eric Offenstadt, which he called the SMAC. Keith had a couple of photographs of this and we said, Right, that’s the way to go, and we built one. The OSSA (monocoque) was a lovely bike, although the welding was a little rough. Ours was quite smooth with no welding showing. We used a TR500 headstock, pop-riveted and glued into place with two front down-tubes. We took it to the Levin circuit for a test day and Rod Coleman had all the test men from Suzuki in Japan along, plus there was Mike Sinclair, John Boote, Stu Avant – all the Christchurch boys came up, plus Geoff Perry and Keith Turner. The monocoque came out and the Japanese were very interested with that. With the (steel) TR5000 frames, unless you got the compression damping on the rear exactly right they wouldn’t handle, but the monocoque was fine straight away. But as it turned out, the combination of the monocoque, the carburettors, and the big two stroke engine – within a couple of laps it got red hot. Keith took it to Singapore and it was so hot there; that’s when we realised the problem, so we abandoned that. That bike was taken to America and they’ve been looking for it ever since.”

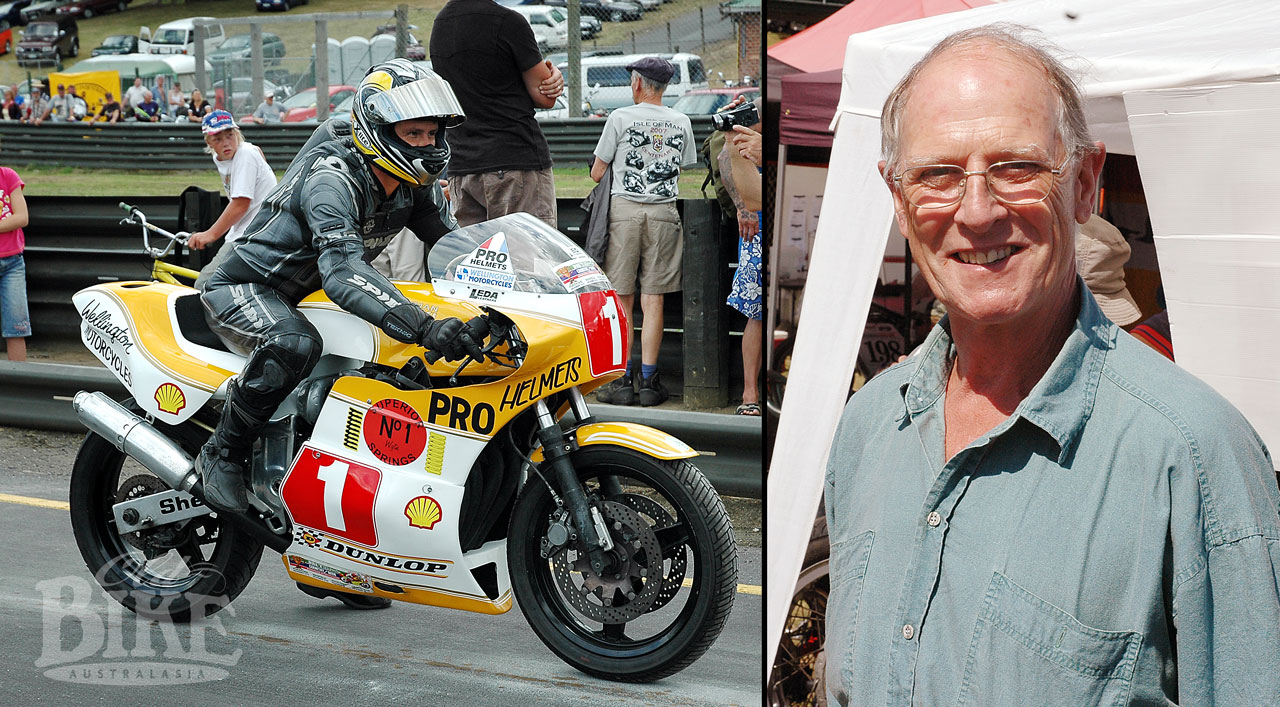

But that was not the end of the monocoque story for Steve, far from it. Working with Graeme McRae on the Leda Formula 5000 and Can Am cars gave him plenty of insight into what worked and what didn’t. It led to the construction of the aluminium monocoque chassis to house a Suzuki GSR1000 Suzuki engine. It was built to comply with the TT Formula One rules, and the plan was to take it to Europe for Dave Hiscock to ride. Prior to the Isle of Man, the bike had a shake down run in a TTF1 Race at Donington, and Dave finished an excellent second, giving the team rise to cautious optimism for the TT itself. In the Island, Dave recorded a standing start race lap of 113.7 mph, but just when things were looking good, the engine ate a piston. A few weeks later, it did the same thing, this time locking up and throwing Dave down the road where he received a serious knee injury. The Suzuki end-for-ended, discarding bits along the way, but it stayed straight, vindicating Steve’s chassis theories.

Another lesson learned from McRae was the process of using pressurised air to increase both performance and cooling ability. McRae told Steve, “You’ve got to enclose the carbs and get equal pressure to the carbs and the fuel tank. We couldn’t do that with normal ducting, so I decided to take the air from the back of the rider – there is an area of high pressure created there – and ram it into the airbox. None of the TTF1 bikes had airboxes – open carbs with bellmouths was thought to be the way to go then – but when we got this working Dave was really excited. He said it was worth at least five horsepower.” Because the ‘chassis’ for the machine (the entire front end and fuel tank/backbone section) was so easy to detach, Roberts and Hiscock even envisaged having separate wet and dry weather configurations, with different head angles.

Some of his early theories in monocoque construction were tried in a radical chopper constructed for an enthusiast known as Earl G. The device used a Suzuki GS1000 engine in a monocoque spine frame, with monoshock rear end and the engine suspended front and rear rather than resting in a conventional steel cradle.

But Steve knew that aluminium fatigues over time, and had bigger ideas. The aluminium chassis steered and behaved extremely well so it was used as the dimensional model for a new chassis made from Kevlar – the so-called Plastic Fantastic. “One of the problems on the aluminium bike was that the rear shock, positioned behind the engine, overheated when the oil got hot. Dave came up with the idea to put the shock underneath the engine with the exhaust pipe running alongside, and we ducted air to it to keep it cool. Moving the shock also gave us more space for the tank. Rod Coleman again sponsored the plastic bike and I began experimenting with carbon fibre and Kevlar. When you hit the carbon with a hammer it would just shatter, but the Kevlar stayed intact. At the time, the police had just been issued with bullet-proofed vests using Kevlar, and I thought – if it can stop a bullet, that’s for us. I used carbon fibre at places for bearings because you can machine it.”

When Suzuki Japan took over the New Zealand distributorship from Rod Coleman, it left Rod with a rare luxury on his hands – spare time. His answer was to begin amassing a serious collection of motorcycles, and putting together a team of experts to fettle, restore and sometimes recreate the bikes, particularly Velocettes. As Steve put it, “Rod got a group of his friends together, one a machinist, one a fitter, me as a tin-basher, and the late Rob Jolly from South Australia to do the castings for him. Rob made the cam boxes and crankcase for all sorts of engines, DOHCs, Mk8s, you name it. At last count we had done 106 bikes between us. We did the frames, mechanicals – the lot, and they’re now all over the world.”

Rod Coleman regards Roberts as a true genius, and says of his incredible project to amass over 100 significant racing bikes, “ The key man, without whom, none of these motorcycle restorations would have been possible, is Steve Roberts, a craftsman par excellence. He made all of the petrol and oil tanks, exhaust pipes and megaphones, plus several different types of frames as well as altering and repairing Webb Girder forks. In all my years of association with him, have never ever seen him in a bad humour or with a negative attitude. I first became involved with him in 1970 when he was working in Wellington. I had been in the USA and managed to borrow one of the first TR 500 Suzukis from US Suzuki and bring it back to New Zealand with Ron Grant to ride it. Ron won everything in New Zealand that season and I then contacted Steve and asked him if he could build a number of frame sets plus tanks etc. No problem he said. At that time there was severe import restrictions on the number of motorcycles that could be imported into New Zealand. Consequently we could not get enough new motorcycles to supply the demand and certainly could not afford to use our available import licences on racing motorcycles. But we could import a good supply of spare parts. My idea was to have Steve make as much as possible of the cycle parts, because Suzuki could not supply them, whilst I negotiated with Suzuki for the special engine parts to convert standard T500 engines into TR500s. Fork assemblies and wheels I got from Ceriani which Suzuki had also done. A couple of the frame sets also went to Suzuki GB for Barry Sheene. Needless to say Suzuki TR500s completely dominated the next New Zealand racing season. I got Steve to move to Wanganui where I employed him in our Suzuki car assembly factory. But Steve being an individualist did not enjoy this type of work so eventually he bought a small farm and set up his own home workshop. We continued our association with racing motorcycles and he designed and built an aluminium monocoque model for Dave Hiscock to take to Europe. But for a few minor problems Dave should have won the British Championship with this. “

At the same time Steve was, and still is, working closely with Ken McIntosh and his booming Manx Norton business in Auckland, making fuel and oil tanks – around 170 so far to suit the various models.

And it’s not just motorcyclists that benefit from Steve’s skills. “I am a sole trader, Classic Car Craft is what I call myself. I try to do one or two cars a year, and at the moment I am doing a DB2 for Aston Martin. There was a Leda (McRae) aluminium tub in the USA which was bent, so I made a jig to straighten it, then another one turned up, and now I’ve had three so far, and there’s another one on the way.” One of Steve’s most magnificent rescues is the Ferrari Monza in which British driver Ken Wharton lost his life at Ardmore Aerodrome in 1957. Wharton lost control of the car entering the finishing straight, the Ferrari somersaulting to destruction and collecting the control tower along the way. The once proud vehicle suffered badly at the hands of predators until it was rescued by the Southward Motor Museum at Parparaumu, not far from Steve’s home town of Wanganui. “You should have seen that when it came in. It had an old Chevy V8 and they had cut the chassis around to get this engine in, and welded bits and pieces on. I had to take all that off, but fortunately they had left stubs of the old chassis. They had taken all the panels off and pop-riveted them back on, but there was one tiny little corner piece left with the original solid rivets so I was able to solid-rivet all the new recreated panels. The Ferrari engine (DOHC 4-cylinder) had gone into a boat, but it was recovered along with a lot of parts and Auto Restorations in Christchurch recast lots of parts and built two new engines. The last car that Len Southward collected was a Zagato Alfa Romeo, and I was given the task of rebuilding that. At one stage I had two Zagato Alfas in my garage – imagine that!”

Steve’s affection and enthusiasm for his work is almost overwhelming. He clearly loves what he does and takes and enormous amount of pride and satisfaction in providing a unique, specialist service that helps other people realise their own dreams. Yet he considers himself to be just a player in a much bigger picture and is modest to a fault.

“I’ve been bloody blessed! I’m just a tin-basher!” he says with utmost sincerity. With his 70th birthday behind, him, Steve, a fit, energetic and incredibly alert and attentive man, clearly has no plans to alter his lifestyle. Luckily for us.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook with assistance from Graeme Staples • Photos: Graeme Staples, Mick Pettifer, Peter Shires, Jim Scaysbrook