In ten years, the Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park had established itself as the equivalent of the Bathurst 1000 four-wheeler classic. The scrutineering was as tough as the race itself, and for the first ten runnings of the event, from 1970 to 1979 inclusive, the original mantra of an endurance event for ‘touring’ motorcycles had been adhered to.

Here the operative word was ‘touring’ and it was up to the organising committee from the promoters, Willoughby District Motor Cycle Club, just how the term was to be interpreted. As far as WDMCC was concerned, touring bikes were not fitted with fairings, but from time to time even this was overlooked, notably with the 900 and 750 SS Ducatis with their ‘bikini’ fairings. There had even been a solitary Velocette Thruxton in the field in 1971, fitted with clip-on handlebars and rear-set footrests- hardly a touring bike in any sense of the word. But the same committee also knocked back the BMW R90S on the grounds that it was fitted with ‘streamlining’, forcing BMW runners onto the ‘naked’ R90/6 for the 1974 race.

If there was any question that the race was now attracting keen interest from the Japanese factories, it was answered emphatically in August 1980 with the announcement that Honda would build (and register) 100 examples of a machine dubbed the CB1100R – specifically to win the Six Hour. Honda had not won Australia’s biggest and most important race since 1971. The original superbike, the CB750, had been outgunned by a succession of models such as the Kawasaki Z1/900, BMW R90 and R100, and the Yamaha XS1100. Just when the new CB900 looked to be in with a chance, along came the Suzuki GS1000, followed soon after by the GSX1100.

When the first photos of the CB1100R appeared it was obvious that it was a single seater, with no provision for carrying a pillion passenger whatsoever. “Oh well, that’s out then!” decreed the committee, until it was pointed out that nowhere in the regulations was it stipulated that to be eligible, bikes had to be capable of a pillion, and, it was rightly argued by Honda, ‘touring’ could be, and usually was, done without a passenger. “Drat!” was the committee’s response, but as the regulations had already been issued, there was nothing to stop the CB1100R from entering – at least in 1980, after which the rules were quickly changed.

Everything starts somewhere, and in the case of the CB1100R, it began with the CB900F, itself a very fine machine, as was its little ‘bro, the CB750F. All three shared Honda’s new-generation DOHC four-valves-per-cylinder technology, and the CB1100R also took items from the 900 including instruments and controls, and the gearbox. The 900 frame received extra gusseting and bracing, with the rake increased 0.5 degrees to 27 degrees 30 minutes, while the trail was up 6 mm to 121 mm. The bottom right frame rail, which on the CB900/750 was a bolt-up item to facilitate engine unit removal, was solid on the CB1100R to stiffen the chassis.

The engine used a single Hy-Vo chain to drive the inlet camshaft while a second Hy-Vo chain drove the exhaust. Despite the 161 cc increase in capacity over the 900, the same 32 mm Keihin carburettors were used. The engine shared the same stroke as the 900 – 69mm – but had been punched out to 70mm bore to bring the capacity to 1062cc – the same as the factory RSC Superbikes. With compression ratio up from 8.8:1 to 10:1. power increased from 70.8 kW to 85.75 kW, with a strengthened clutch and overall final gearing raised by 10%. The cylinder block on the CB1100R was solid, unlike the smaller units which had an air-gap between the outer two cylinders.

New 38 mm forks featured air-assistance, with a balance tube running between the two legs. At the rear, the suspension units had an oil reservoir added, finned for cooling and removable for filling. Twin 300 mm front discs with two adjacent pistons in the floating calliper were a marked improvement over the 900 front stoppers with fixed calliper and opposed pistons. Bespoke items included the 26 litre alloy fuel tank, fibreglass seat, alloy footrests, brackets and clip-on style handlebars, and the black-finished four-into-two exhaust system with its cross balancer.

Unsurprisingly, the CB1100R was not much of a road bike, at least in addressing the traditional areas of comfort and convenience. The engine rumbled at mid-revs, with vibrations transferred through the footrests and rendering the mirrors useless, the seat was virtually bereft of padding, there was no centre stand, and the limited turning lock meant low-speed manoeuvres were risky. The clip-on style handlebars were almost infinitely adjustable and could also be changed quickly in the event of a prang.

Amaroo Park placed considerable demands on ground clearance, particularly on the right hand side. To this end, both crankshaft end covers were reduced in size and chamfered, the exhaust headers tucked well in, footrests raised and mufflers kicked up out of the way. Honda claimed the bike could be banked to 50 degrees on either side before anything scraped. In the race, several were banked beyond 90 degrees. One of the areas that handicapped the CB900 was the 2.15 front and rear rims, severely restricting tyre choice. On the CB1100R, the rear grew to 2.75 x 18 and the front to 2.5 x 19. The wheels were the now-familiar Comstar pattern, made front from alloy pressing riveted to alloy rims.

For 1980, Suzuki countered with the specially-produced GSX1100 ‘Six Hour Special’ – 120 examples of which were imported, sporting a wire-spoke 18-inch rear wheel, as opposed to the standard version with a heavy cast-alloy 17-inch rear. At the time, there was no 17-inch rear tyre capable of containing the ever-expanding horsepower figure of the Japanese 1100s, hence the switch to the bigger (and lighter) rims. On paper at least, the Honda looked to have the Suzuki challenge well covered. The CB1100R weighed 14 kilos less and produced 10kW more power, with better brakes and ground clearance.

Massing the troops

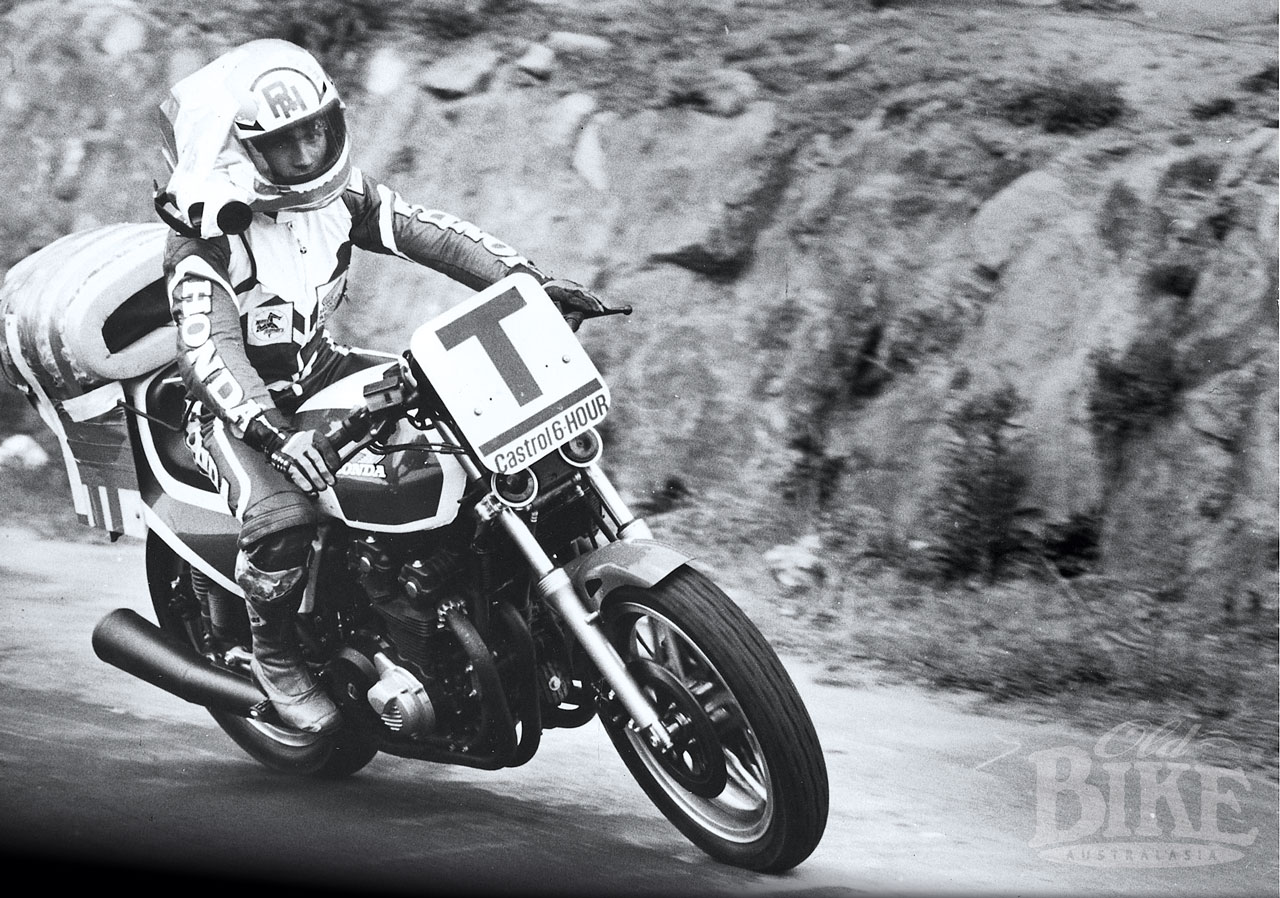

When entries closed for the 1980 Castrol Six Hour Race, no fewer than eight teams had opted for the new Honda, ranged against seven wire-wheeled Suzuki GSX1100s plus one alloy-wheeled version. Aboard the red and white machines were the pairings of Honda Britain star Ron Haslam/ Kenny Blake, Dennis Neill/Roger Heyes, Alan Decker/ Mick Cole, Jim Judd/Rick Fiddoch, Peter Byers/Rob Reed, South Africans Rod Gray/Dave.Woolley, Terry Turner/ David Burly, and Andrew Johnson/Wayne Gardner. Suzuki GSX1100-mounted were Neil Chivas/John Pace, Dave Hiscock/ Alan Hales, Malcolm Campbell/Rod Cox, Hilton Steel/Ian Standen, Glenn Fenton/Max Heaton, Rob Phillis/Graeme Muir, Gary Vincent/Andrew Thompson and Rob Scolyer/Craig Bye on the alloy-wheeled model.

Final qualifying was a thrilling shoot-out that showed just how close the rival marques actually were. Dennis Neill claimed pole with a blistering 56.13 second lap – 1.57 seconds faster than his 1979 pole on a CB900. Mal Campbell’s GSX1100 was just 0.25 seconds adrift, with Gardner third on 56.66. Such was the fierce pace of the tyre war, not a single runner used the previously-dominant Avons. Instead, Pirelli had the numbers from Metzeler, although many of the favoured teams chose a Pirelli front with a Metzeler rear.

As well as the on-track action, pit crews were drilled and re-drilled for refuelling and wheel changing. The Honda gained a few more seconds on its rivals with a rear wheel that was in and out in around 45 seconds.

After his sensational qualifying lap, Neill – a dry-track specialist – had his hopes sink when race day dawned damp and dreary. By the time the 39-strong field lined up for the Le Mans-style start, it had been raining for more than one hour. Tyre choices were out the window. Neill abandoned his plan to start the race and handled the pole-sitting Honda to team mate Roger Heyes. From the Le Mans start, Gardner grabbed the early lead as the field splashed around, but within a couple of laps, John Pace was through to lead on his Suzuki. From that point on, there were effectively only two bikes in the race. Wayne kept a watching brief for half an hour, then pushed through to establish a gap that was big enough to hold the lead even through five pit stops. After two 90-minute back-to-back stints, Gardner handed over to Andrew Johnson for another two hours, then took the seat for the remainder – or so he thought. With 45 minutes remaining, he was back in the pits to un-kink a fuel breather hose, but on a drying track, held out Neil Chivas’ final charge to rack up 322 laps before the chequered flag fell at 4pm. Four laps adrift came the Heyes/Neill CB1100R. As a measure of the conditions, it was the lowest lap tally since the very first Six Hour in 1970. Much of the opposition simply eliminated itself, with Haslam, Turner, Graeme Muir, Alan Hales, Neville Hiscock and Alan Decker all dropping their mounts. Honda had won the victory they so desired, but had only two 1100s in the top ten, albeit in first and third places.

Slip sliding away

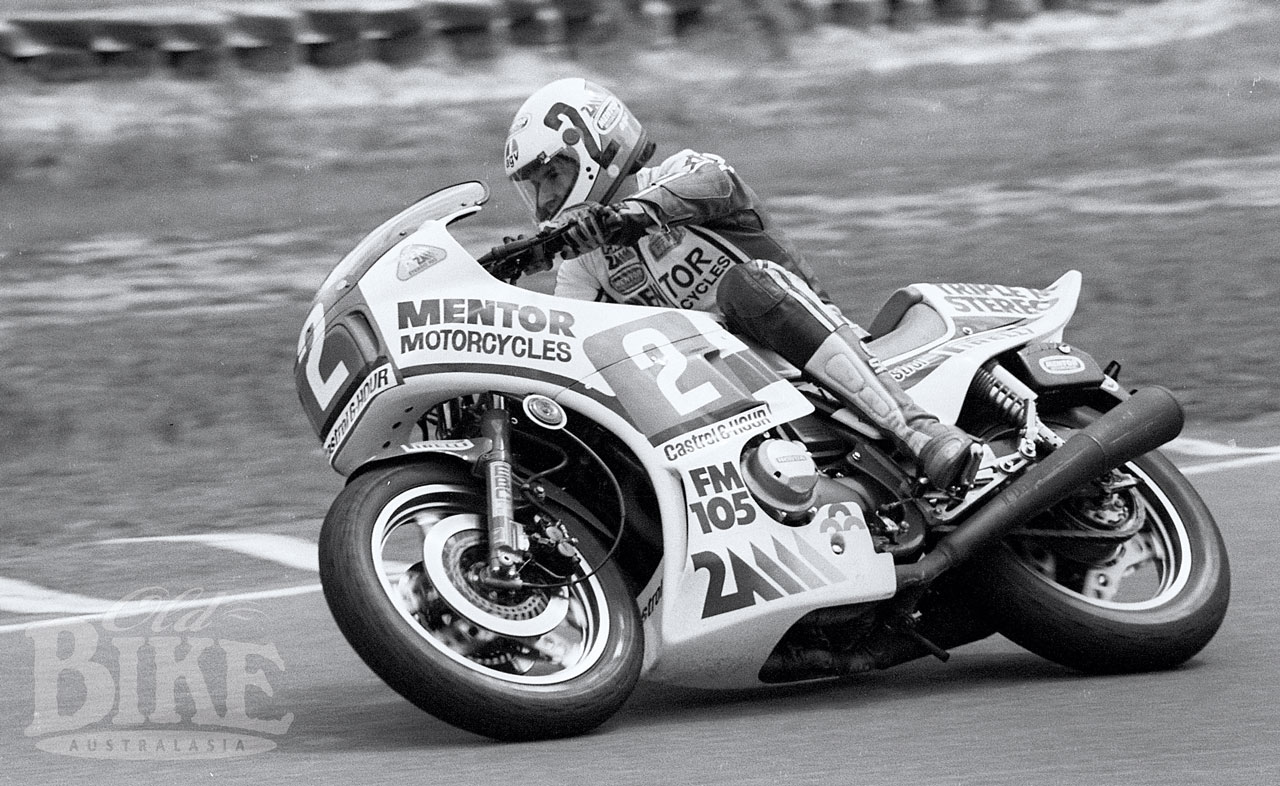

My personal experience of the 1980 Castrol Six Hour-winning CB1100R brings back memories of a frustrating and ultimately painful Easter weekend at Bathurst in 1981. My mate Terry Pinson had purchased the winning Honda from Mentor Motorcycles shortly after the 1980 Six Hour, ostensibly to use as road transport and as ‘a bit of an investment’.

With nothing lined up to race at Easter, I managed to convince Terry over a few beers to enter the bike for me in the Unlimited Production Race – the 20-lap, 122 kilometre thrash that was the highlight of the program for many. The thrills came quickly in practice – on the first full-bore run down the 1.5km Conrod Straight. At around 240 km/h the Honda would begin an oscillation that was unnerving to say the least – not so much a wobble but a slow, synchronised weave. It made cresting the humps in Conrod (there were two in those days) a rather scary affair, but the weave did not seem to get to the point where the bike felt like it was about to go out of control. At least I didn’t think so. The Clerk of the Course however, had other ideas, and a few laps into the practice session I was shown the black flag at the start line.

Back into the pits I was ushered smartly into the scrutineering bay, where the Travelling Marshall and several people with important looking armbands were gathered. They were clearly discussing the Honda’s serpentine progress down the straight. As soon as I had my helmet off, the Clerk of Course directed questions at me regarding my sanity, while the armband brigade launched into a major investigation of the bike itself. I remonstrated about the lost opportunity for practice, at which point I was told to behave, and the scrutineering sticker removed from the bike. Pretty soon, the Honda was in a million bits – shocks removed and dismantled, swinging arm pivot checked, engine mounts tightened, steering head, wheel bearings – you name it. Hours later, the Honda had been meticulously reassembled just in time for the second vital practice session, and I set off with the stern warning that the powers-that-be would have their eye on me.

First time down the straight and, lo and behold, it was exactly the same. I realised that my number would soon be up (on a black flag again) so I squeezed in a few more laps and made sure I was looking down at the engine as I passed the pits (and the black flag) each lap. Next time around, the Travelling Marshall was stationed at Murray’s Corner and with an authoritative finger made it clear I was to go no further. Again the bike disappeared into the scrutineering tent. With nightfall approaching I disappeared into the beer tent.

Rubber cure

Bright and early the next morning all was revealed. The tyres – Dunlop K81s – were the culprit. Even the Dunlop guys admitted it. On went a set of Pirelli Phantoms and out we went for the race. On the warm up lap I gave it heaps down the straight and there was not a trace of a wiggle, wobble or other aberration. Marvellous things these tyres. Halfway through the race and running in tenth place, I thought things weren’t quite right in the engine department, which had developed a few rattles and didn’t seem too sharp any more. Would it survive the race? We’ll never know. Entering The Cutting for the 11th time, I dived under a rider, cutting the corner closer than before and dangling a knee in the grass. Hiding in the growth was a lump of asphalt, left over from the recent track resurfacing, about the size of a bowling ball, and it came in contact with my kneecap with a sound like a sheet of fibro breaking. Exit to the Casualty Ward at Bathurst Hospital where I joined Wayne Clarke (broken leg) and seven or eight other riders.

The post mortem on the Honda revealed the cam chain tensioner had dropped its guts, and would certainly have caused major damage before the scheduled 20 laps had been completed. At least my smashed patella had not been completely in vain. The aforementioned tensioner is certainly a major weak point on these otherwise robust engines, and there were soon after-market items and a genuine replacement of a beefier design available.

Terry’s ‘investment’ thereafter enjoyed a slightly less hectic life as road transport, with the optional dual seat and passenger footrests fitted. I say ‘slightly’ because Terry does press on a bit, and one such spirited tour ended in the Honda spinning down the road, destroying the unique black-chromed exhaust system. An O’Brien four-into-one system went on as a replacement, but Terry now regrets dumping the clobbered but probably recoverable original system, as they are now unprocurable as a genuine part, although there are people around the world who will build them from scratch, at a hefty price. Then you need to have the pipes and mufflers black-chrome (or matt black for the RC/RD models), another pricey exercise. Otherwise the bike is still exactly as it came off the track at Amaroo (and Bathurst), even down to faded 2MMM and Bel Ray stickers, and unrestored paintwork in the Mentor/Molloy colours. And with some recent sales of the original 100 bikes fetching around $20,000, it would appear his investment has paid off. It is currently on display at the National Motor Racing Museum, Bathurst.

Episodes two and three

Despite the CB1100RB’s world debut win in the 1980 Castrol Six Hour Race, success was scarce after that, with the Suzuki GSX1100 scooping most of the major honours. To twist the knife, the Six Hour promoters announced that the CB1100R would be ineligible for the 1981 race as it had no pillion-carrying provisions, so a re-think was in order. The new CB1100RC overcame the problem with a ‘dual’ seat along the lines of the Ducati Pantah concept, whereby the rear section was detachable to convert it from single to dual two person use. Fitting pillion footrest was a fairly simple matter. Visually, the ‘C’ was totally different, clothed in a rather bulbous full fairing.

Inside the engine, a practical and necessary modification was a stronger cam chain tensioner. For the Australian, English and French models power output was unchanged at 85.75 kW (115 hp) but models sold in New Zealand and South Africa (the General Export specification) had 88 kW (120 hp) on tap. Mechanically, the main changes were to the chassis, with the front end raked out a further smidgin to 28 degrees and the trail decreased from 121 to 113 mm – basically to cope with the new 18 inch front wheel to replace the now out-of-fashion 19 inch hoop. Front fork diameter went up to 39 mm, with a four-way adjustable anti-dive system activated by a hydraulic valve in the forks. This system, which Honda called TRAC, basically came from the CX500 Turbo. At the rear, the FVQ shocks did a back-flip to mount upside down, with a remote gas-filled reservoir, four-way adjustable rebound damping and three-way compression damping. Brake callipers were the same as the B model, but the front discs were now ventilated. The wheels were still of the composite style pioneered by the ‘Comstar’ design used on the B, but were now a “three-spoke” style (also from the CX500 Turbo) with wider rims; a 2.50 up from and a 3.0 at the rear, although a 3.5 rear rim was homologated for South African racing.

The addition of the fairing meant the instruments were now contained within the cowling, the tacho being electrically operated rather than cable-driven. The changes initiated on the C-model made little difference to the machine’s suitability as a road bike; it was still a racer through and through. At the all-important Castrol Six Hour Race in October 1982, Len Willing smashed the qualifying record with a 55.8 second lap, but the Honda now had a new rival in the form of the Suzuki Katana. The race would be a milestone in one sense; from 1983, the upper capacity limit for Australian Production Racing would drop to 1000 cc – making the 1100s obsolete. In a highly controversial result due to questions over the lap scoring, the team of Wayne Gardner and Wayne Clarke took victory by just four seconds – with Honda CB1100RCs in the first four positions and all on 367 laps.

The change in regulations meant Honda runners switched to the new V-four VF750FD for 1983, but even with no category left to run in, there was one more model of the CB1100 R left to run. The D model differed little from the C apart from the rear shocks and the swinging arm, which was now rectangular section and wider to allow for fatter rear tyres. Carbs remained at 33 mm, and power output was now officially listed as 120 hp. The RD fairing nose was shortened significantly to be behind front axle centerline to comply with latest racing regulations and the décor had altered slightly, with a lighter metallic blue replacing the solid blue on the C. It appeared towards the end of 1982 and remained in limited production for less than 12 months.

Look at any of the numerous web sites and most will list the production of the CB1100R from 1981 to 1983, with yearly output of 1050, 1500 and 1500 respectively. Clearly, there’s something amiss here, because there were certainly 100 bikes in Australia by September 1980, plus a few in South Africa. The CB1100RB was first shown in Britain at the Earls Court Motorcycle Show in October 1980 wearing a half fairing, but the un-faired Australian models were fast-tracked to meet the entry cut-off for the 1980 Castrol Six Hour Race.

We’re indebted to the Australian Motorcycle Museum at Haigslea, Queensland for the very opportunity to sit all three models of the CB1100R beside one another. Their RD is an especially rare treat, with just 32 kilometres on the clock, and most of that from being pushed between various locations – a real time warp.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Technical assistance from Michael Hayward • Photos: John Ford, Bill Forsyth, Graham Munro, Jim Scaysbrook