From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 86 – first published in 2020.

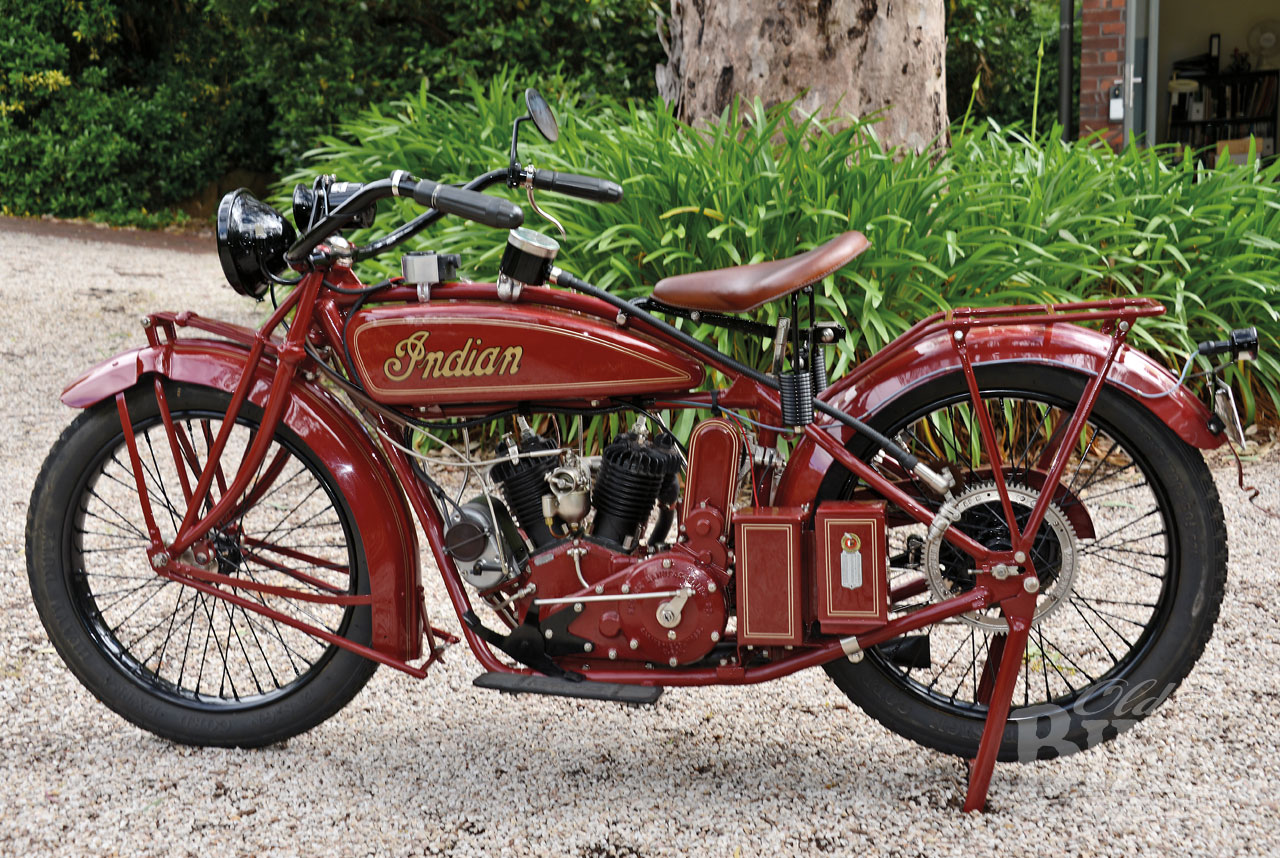

When it comes to his meticulous restorations, Rob Elliott shows no particular leaning towards any make or model, or even period. He has tackled veteran motorcycles, plus later models from various British and Continental manufacturers, and now the latest to emerge from the workshop after an eight-year restoration, a 1924 Indian Scout.

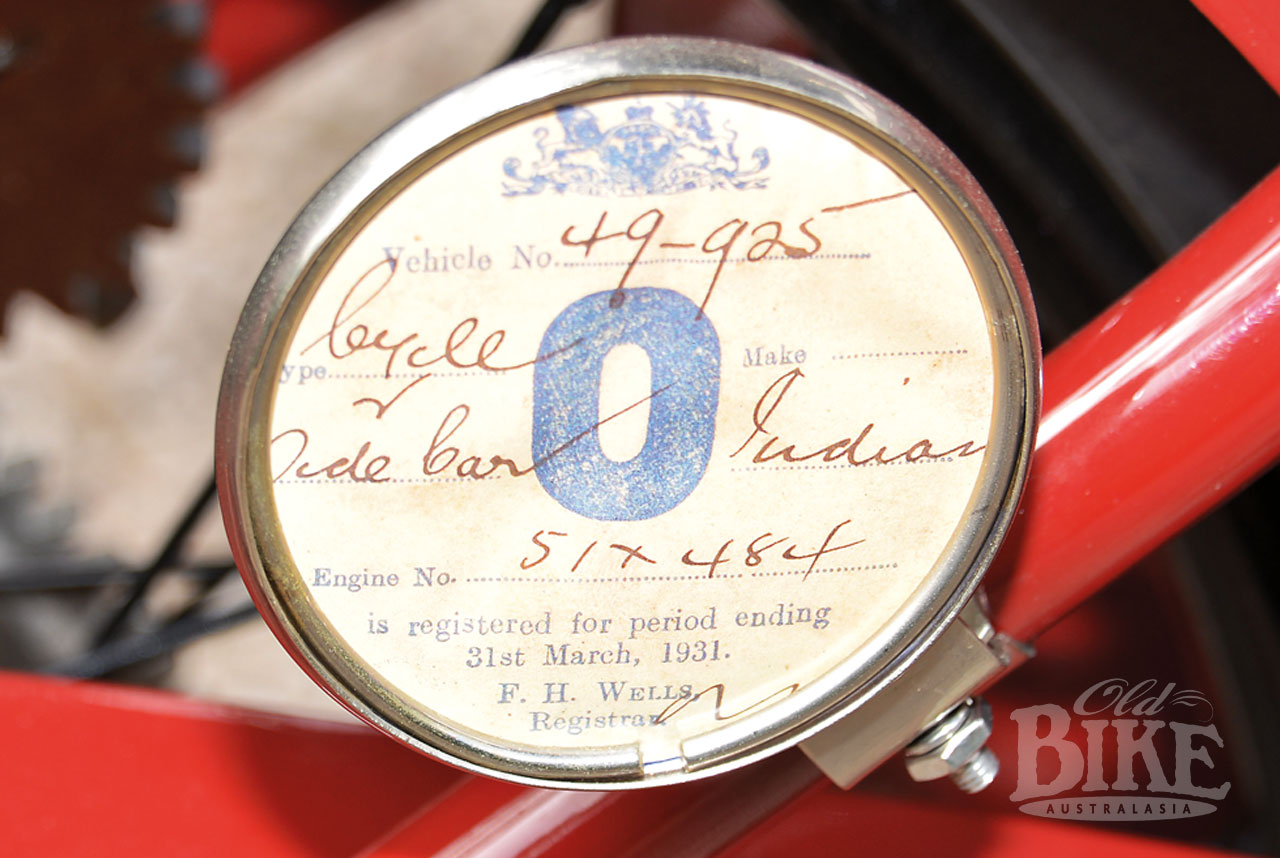

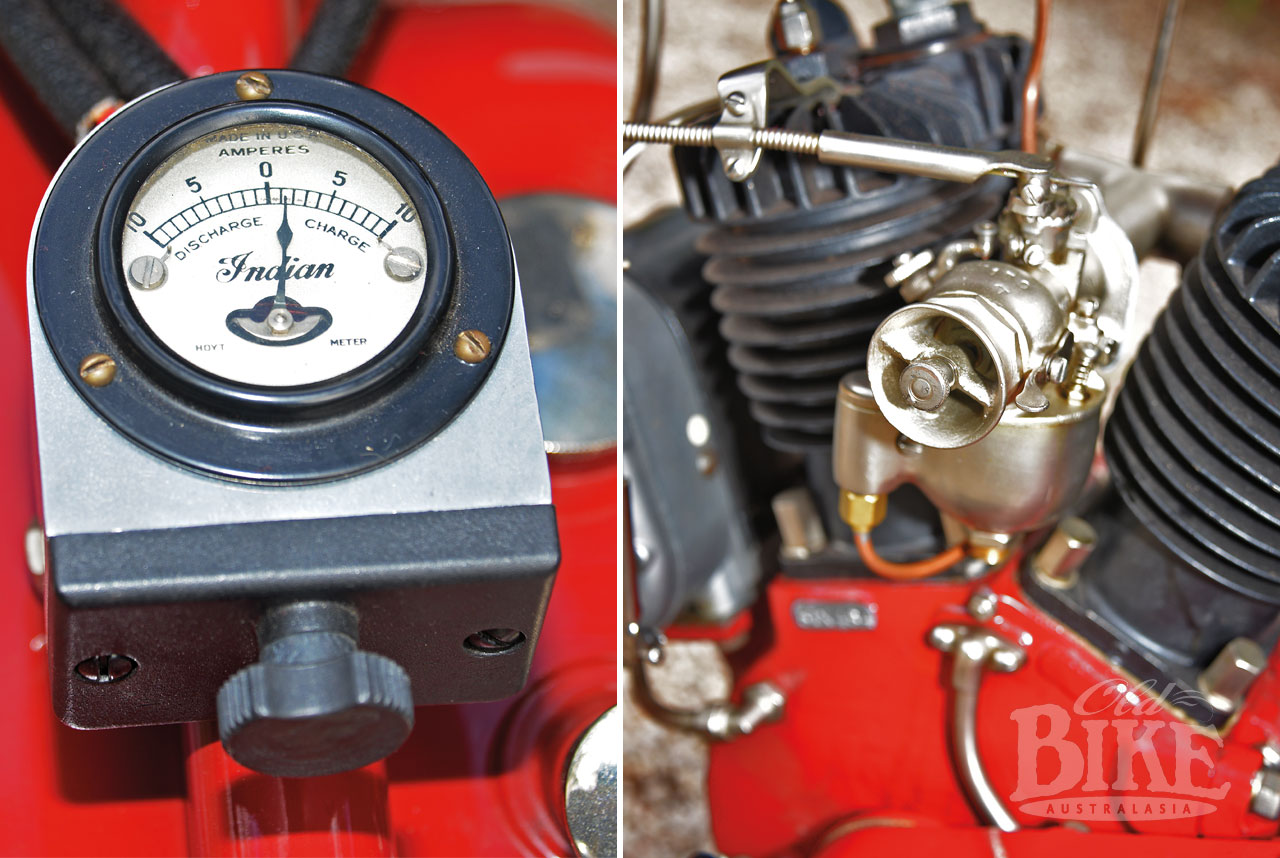

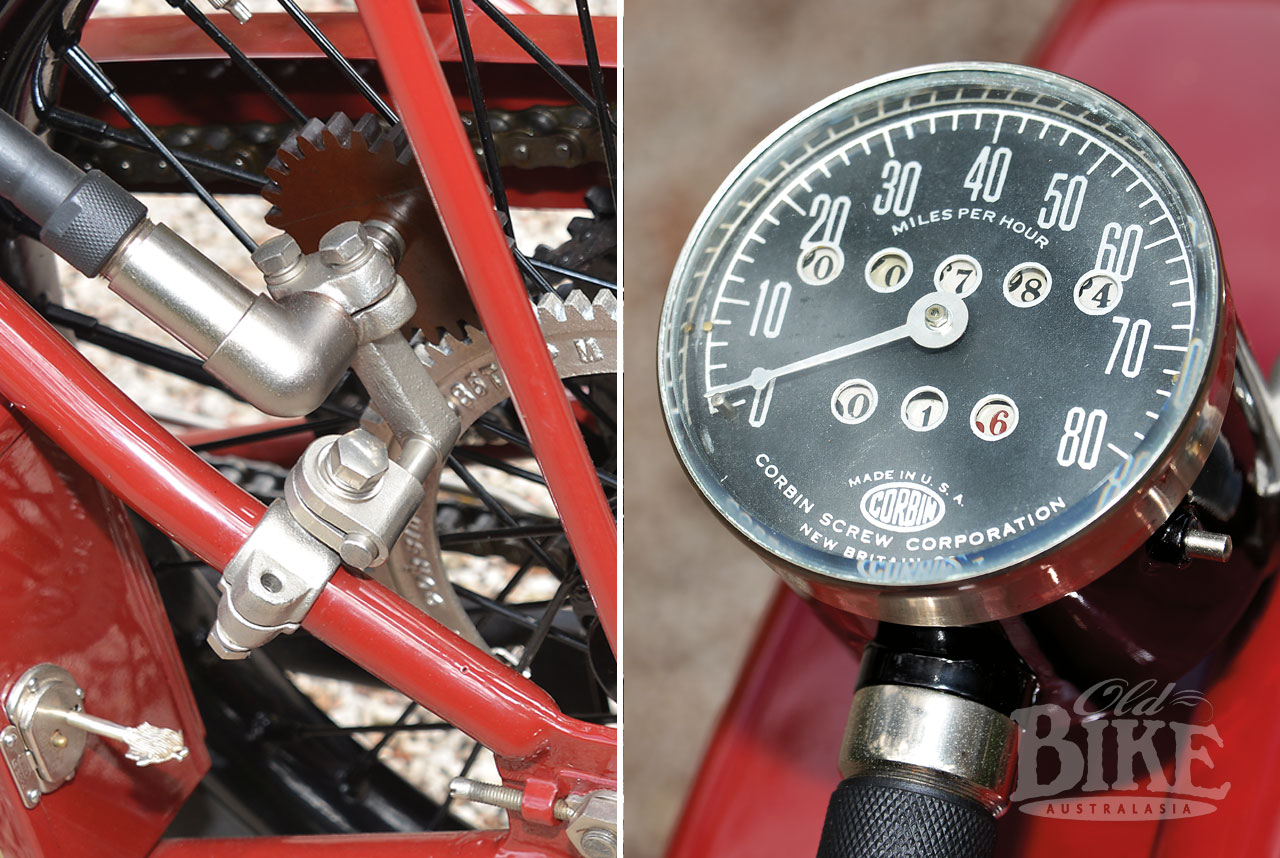

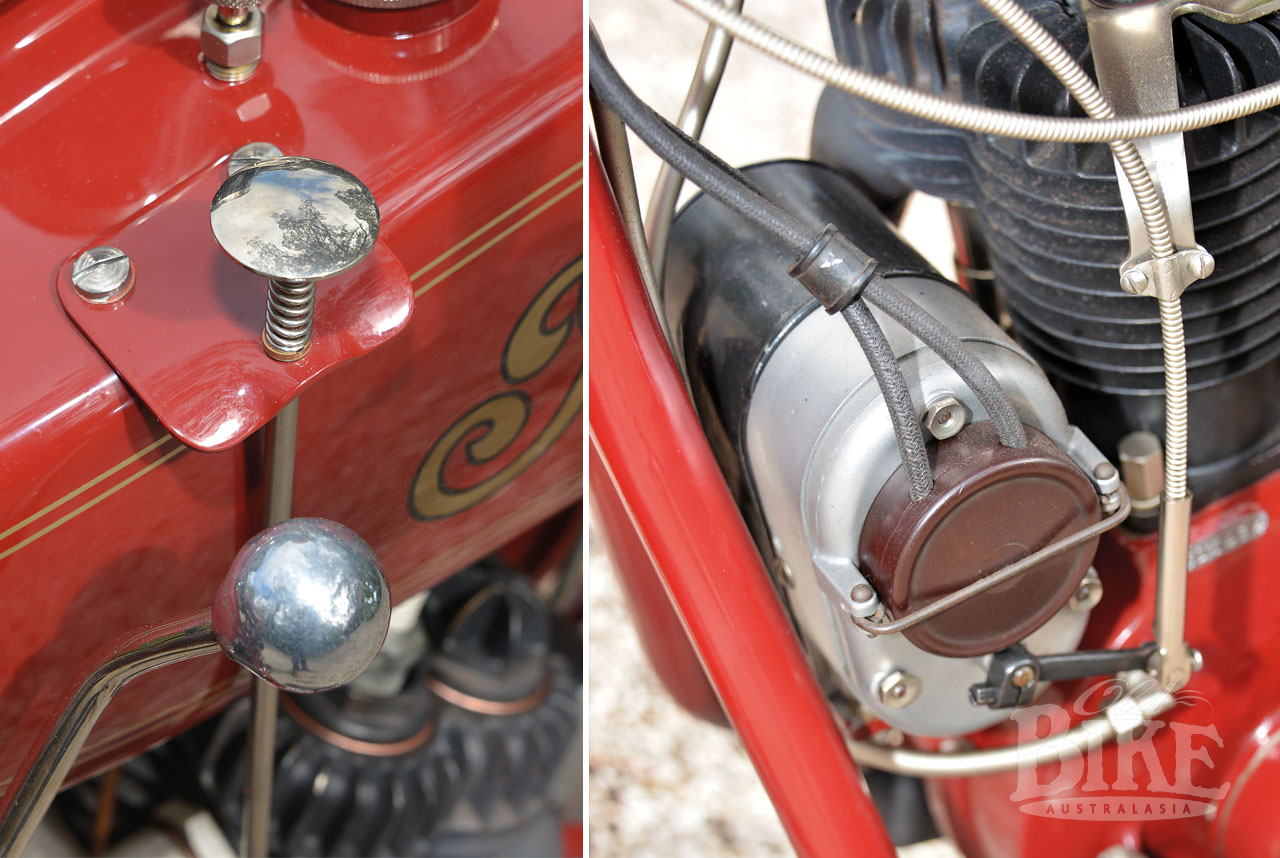

Like many of Rob’s bikes, this one has a strong Adelaide history, being bought by the bike’s second owner from South Australian Harley distributors Lenrocs in 1929. Rob is only the fourth owner of the bike and believes the 600cc twin was last registered in 1930 – he has the original Hire Purchase papers from Lenrocs, plus a letter to the owner from the workshop of ex-Indian racer Edgar Fergusson. It came with crates of original parts, plus a Yeats sidecar, which Rob says added weight that the Scout struggled to cope with. This was soon discovered after being initially recommissioned for Rob by friend Phil Jenner. The majority of the restoration work, however, was undertaken by local Indian expert David Cant. Working full time as an R&D manager at the time, Rob helped David by organising such things as painting, plating and doing some of the “jewellery” work, including refurbishment of the speedo, the wiring and other electrical components.

The Scout: Indian’s saviour

By the end of the Great War, Indian wasn’t in particularly good shape. Despite making good money from wartime contracts, the supply of motorcycles for the US military had been at the expense of the civilian market. As a consequence, the company lost dealers to rival brands, notably Harley-Davidson, while the Indian name slipped down the civilian shopping list. It was a far cry from the pre-WW1 era, when Indian was probably the world’s top brand, with a solid model range, racing successes across the globe, and robust sales. But by 1919 the range, consisting of Powerplus singles and twins, was tired, and the company struggling with dithering management. A change was needed, and quickly.

That change had its genesis in a multi-talented Irishman, Charles Franklin, who enjoyed a 13-year racing career commencing in 1903, with many successes including second place in the 2011 Isle of Man TT riding an Indian. He was so successful at Brooklands that the handicappers punished him to the extent that it made it impossible for him to win. He also competed extensively in Europe, and had the 1911 French Grand Prix shot to pieces until a series of punctures dropped him to third place. He was inextricably linked to the Indian brand throughout his racing career. Moreover, Franklin had been an Indian dealer and later the manager for the Indian Depot in Dublin until it was forced to close in 1916 due to new laws restricting the importation of motorcycles made abroad. This coincided with the retirement of Indian company president George Hendee, and the subsequent restructure of the management. Franklin received an offer to travel to Springfield, Massachusetts, to take up a position with Indian’s design department, initially for six months. He arrived in November 1916 and went straight to work.

As popular and successful as the Powerplus was, Indian could see they needed more than the traditional big and heavy v-twins, particularly in the face of America’s growing fascination with the motor car. Although Charles Gustafson Senior was Indian’s head of design, the chalice for meeting the company’s future challenge was firmly in Franklin’s court, and his response was the Light Twin (Model O). Within two months of commencing work at Indian, prototypes were already in existence. The engine was a fore-and-aft flat twin in the style of the successful Douglas, with its inherent perfect primary balance. But it was slow, unexciting and failed dismally to attract new motorcyclists, so much so that it was dropped after just two years in production.

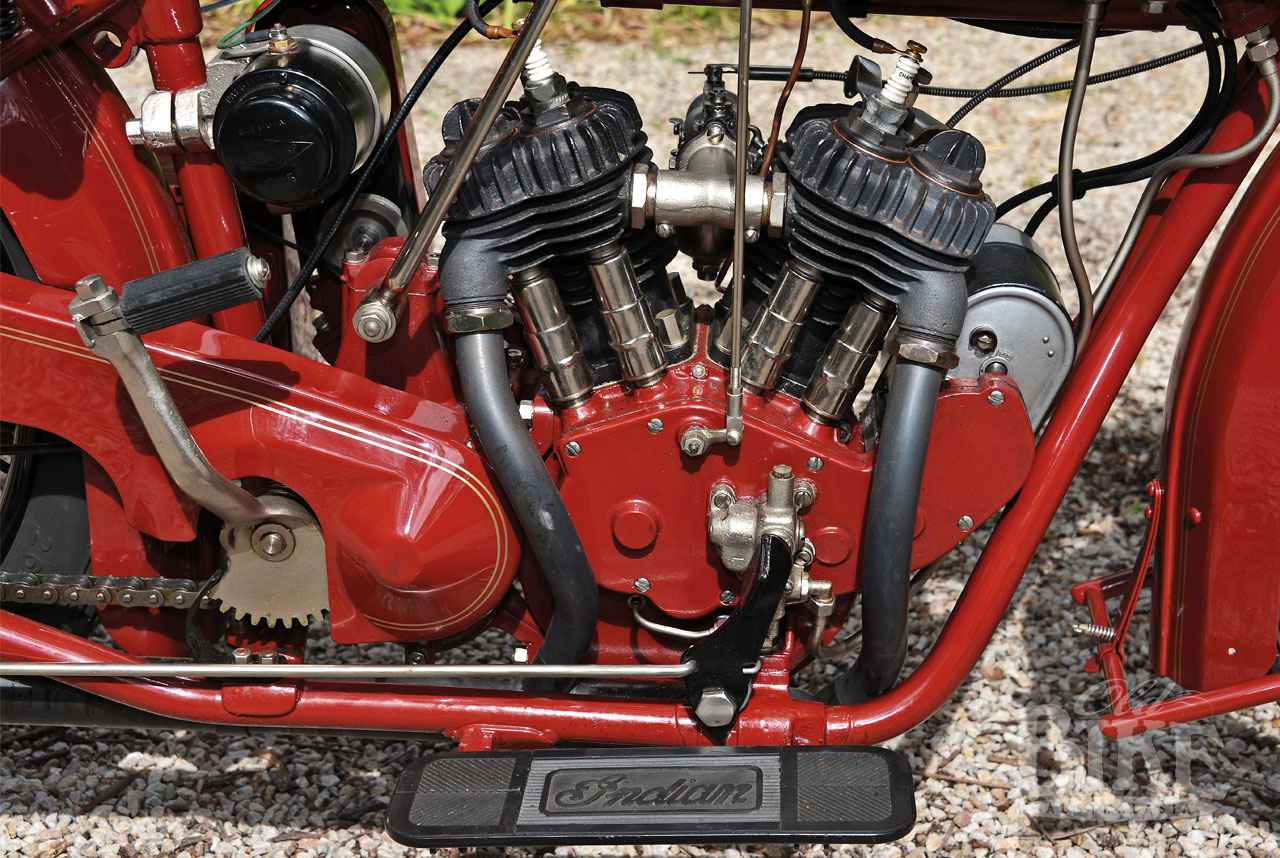

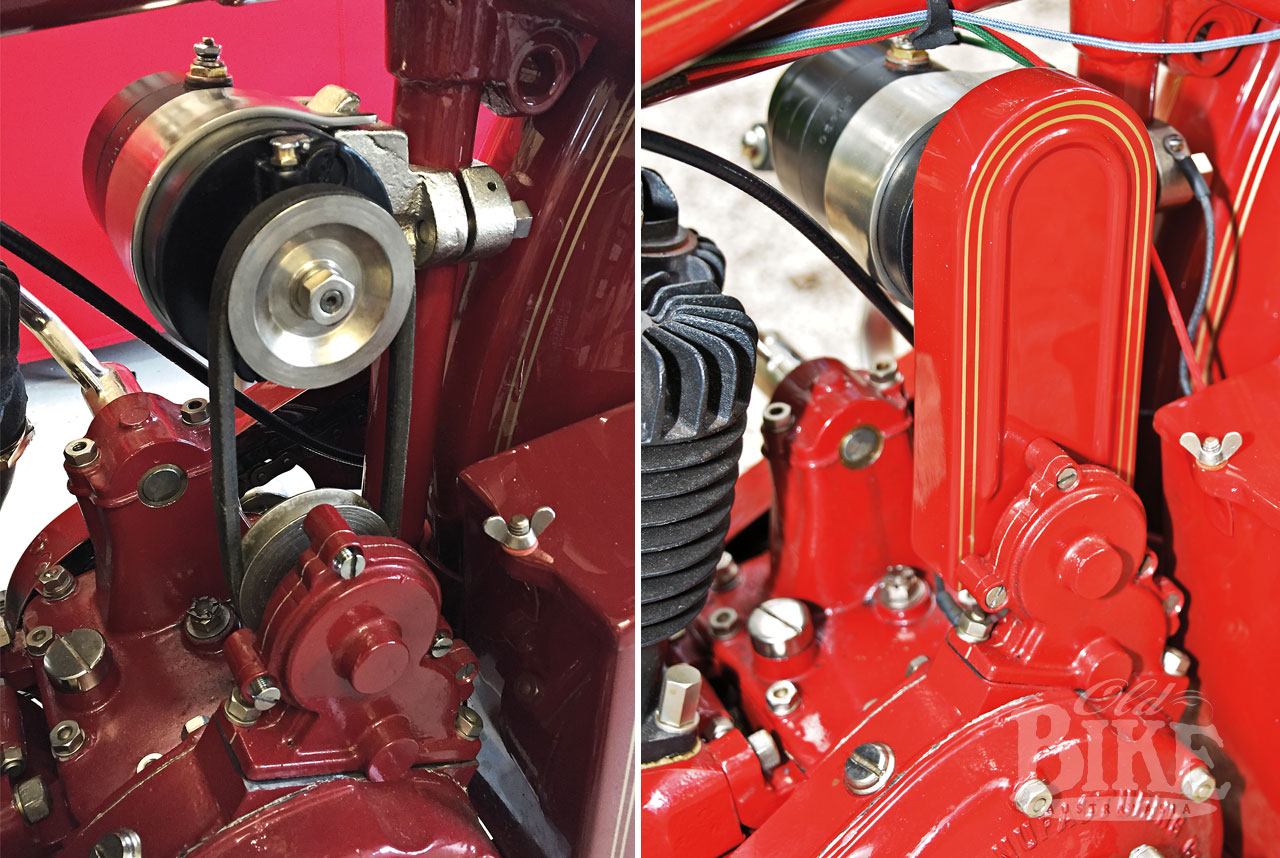

At one stage it looked like Franklin would be sent to Europe to look after the Indians used by the US Army, but when that failed to eventuate he quickly went back to his drawing board. The result was the Scout. This time there was no thought of anything other than a v-twin; no gasping two stroke (the Featherweight of 1916) and no quirky flat twin. The Scout needed to be considerably lighter than the Powerplus, less bulky, more manoeuvrable and easier to maintain. There was also the question of manufacturing economies – something hammered by the company accountants, so the desire for fewer components dictated the choice of side valves, arranged side by side as on the Powerplus. This also kept the height of the engine low, and contributed to the Scout’s compact overall dimensions. Capacity for the Scout was settled at 596cc (or 37 cubic inches), with two camshafts instead of the Powerplus’ single cam. The complete timing train was gear-driven from the exhaust cam to the magneto.

Bolted to the rear of the engine was the 3-speed gearbox, providing a semi-unit construction engine/transmission package. This feature was hugely significant for several reasons. By adopting a helical gear primary drive, there was no need to build in a method of adjustment for the usual primary chain, and dispensing with the chain eliminated one of the messiest and most annoying duties for the home mechanic – adjusting the chain by either pivoting the gearbox or tensioning it by other means. The single engine/gearbox unit also allowed the elimination of separate mounting brackets or tubes, in fact, the unit was held in the frame at just three points – two at the front and one at the rear, and could be removed quickly and easily. The result was a very stiff structure that resisted twisting under load.

Another major innovation was the double loop full cradle frame, with two tubes running down from the steering head and along each side of the engine back to the rear axle, with the various lugs brazed together rather than bolted up. Front suspension was the familiar leaf-spring trailing link tubular steel girder fork, with a rigid rear end, which was simple and cost effective.

Up and running

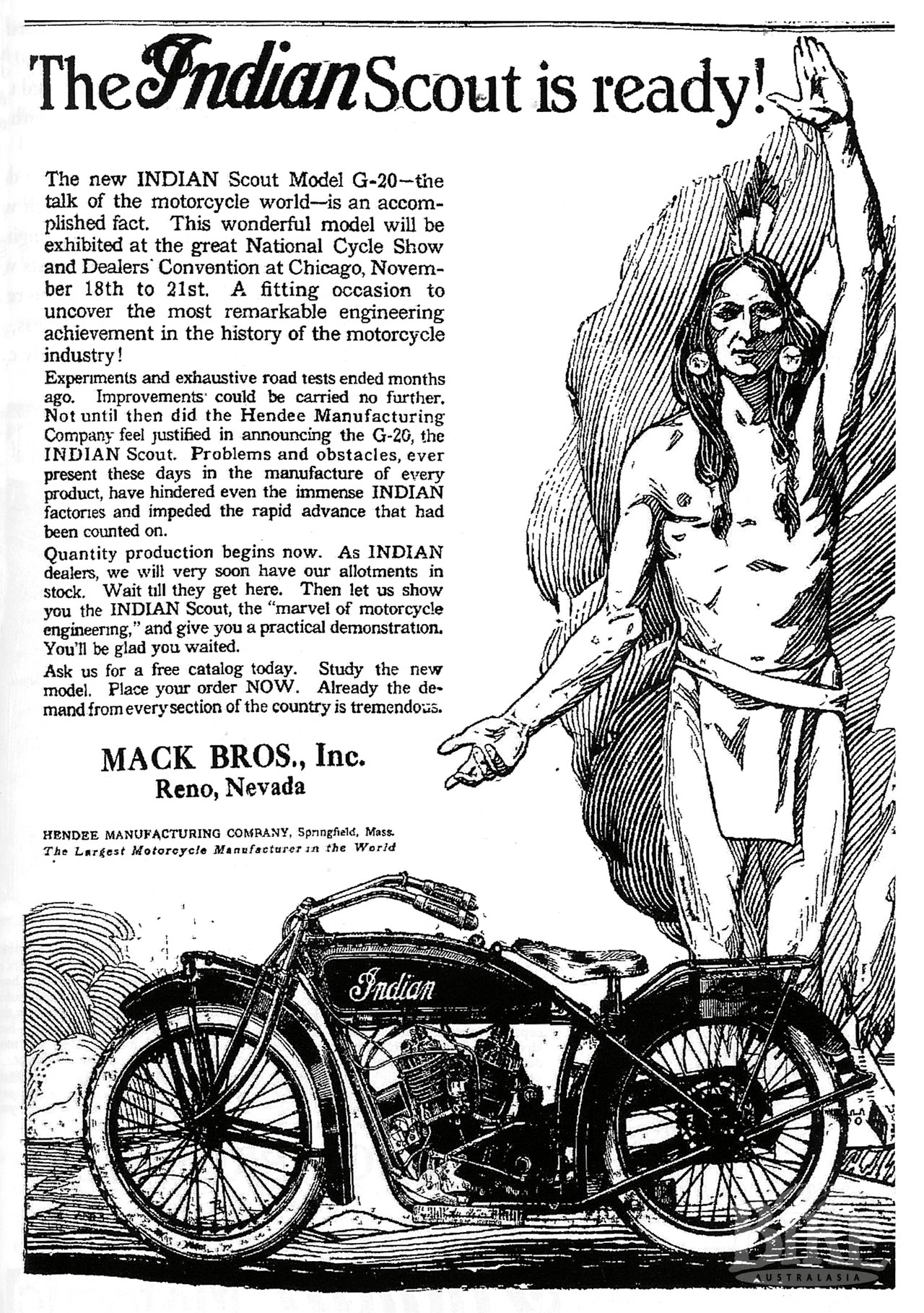

During 1919, a prototype Scout had been constructed and tested, and soon several pre-production models were undergoing more strenuous tests; by all accounts passing with ease. The National Motorcycle Show in Chicago from 18-21 November, 1919, was selected as the public launch of the Scout, where it was received with rave reviews. It was light, compact, easy to start, and comfortable to ride with its low saddle height. Prior to Christmas 1919, listed as a 1920 model (the G-20), the Scout was in dealers’ showrooms; at least those dealers that had stuck with the brand. Advertisements of the time modestly proclaimed the Scout as “the most remarkable engineering achievement in the history of the motorcycle industry!”

The Scout’s introduction almost coincided with that of its chief rival, the flat-twin Harley Sport, also of 600cc, introduced earlier in 1919. But when it came to the sales race, the Scout demolished its nemesis, to the point that the H-D Sport was de-listed from 1923. Initially at least, Indian was unable to meet the demand for the Scout, while unsold examples of the H-D Sport piled up in dealers’ yards. The Milwaukee company set its designers to work on a replacement with which to combat the Scout, the result being the 750cc Model D of 1928.

As well as sales successes, the Scout was soon clocking up records, including 1,114.25 miles (1793.9 km) in 24 hours, an average speed of over 50 mph, ridden by the mercurial Harold ‘Ranji’ Parsons on a triangular course between Maffra and Sale in Victoria, coincidentally beating the existing 1916 record (by 250 miles) of ‘Cannonball’ Baker on an Indian Powerplus. Across the ditch in New Zealand, Burt Munro happily forked out £120 for a new Scout and kept it for fifty years, albeit modifying it completely in the process.

Onward and upward

Franklin and his family had become US citizens in 1922, and his stocks soared on the success of Scout. He was soon made Chief Engineer and given another clean sheet of paper to design what would emerge in 1922 as the 1000cc Indian Chief, followed a year later by the 1200cc Big Chief. Both mirrored the Scout’s side-valve design, and the 1200 remained in production until the very end of the company in 1953. But Franklin wasn’t finished with the Scout either, which became the Model 101 in 1928 in 45ci (750cc) form. The engine was a stretched version of the original, which had first been seen on the Police Special, and the frame a longer wheelbase by about three inches, with an even lower saddle height. Perhaps the new Scout was hurried into production in response to the threat from the Chicago-based Excelsior company, which was enjoying considerable sales success with their 750cc Super-X which came on board in 1925.

The new 45ci (750cc) Scout had the 37ci engine’s dimensions of 2 ¾” bore x 3 1/16” stroke increased to 2 7/8” x 3 ½”, using basically the same bottom end which had proven to be very robust in the smaller size (which continued in production). Marketed as the Scout 45 ‘Police Special’, the new model made its public debut at the New York Motorcycle Show of January 1927, and boasting a top speed exceeding 80mph, was soon capturing plenty of sales. Ironically, some of these sales came at the expense of the company’s own Chief. By mid 1928 the Model 45 had become the 101 due to a change of model policy by Indian (the 401 being the 4-cylinder model, and the 301 being the Chief). The 101 sported a longer 57” wheelbase frame, was lower overall, and for the first time on a standard Indian, was available with a front brake – a nod to the rapidly improving roads and the speeds attainable on them by modern motorcycles. Extra performance was gained from new cylinder heads with ‘squish’ combustion chambers developed in racing, while subtle styling changes, notably to the fuel tank (which was still mounted within the frame tubes rather than the ‘saddle’ style that was appearing on many other makes) with a more ‘teardrop’ shape.

But while his designs were going from strength to strength, Franklin’s health was doing the opposite. In 1931 he was given a leave of absence in order to rest and hopefully recover energy and fitness, but rather than take it easy, he set up a drawing office in his home where he continued to produce many new designs and modifications to existing components. By 1932 however, his condition had deteriorated to the point that any further work, even from home was impossible, and he passed away on 19th October, 1932 at the age of just 52. The official cause of death is reported as “acute myocarditis”, or heart failure.

An owner’s perspective

Rob Elliott describes the process whereby he acquired and rebuilt the 1924 Scout featured here.

“Finding the Scout was, fittingly, a lucky accident. Readers may recall the story of ‘The Good Luck Bike’, my Swastika JAP in OBA 46. It was while researching the history of the Swastika that I talked to a cousin of one of that bike’s owners in the ‘60s. When I phoned him he unfortunately didn’t know much about the Swastika JAP’s past, but did mention that he had a non-runner Indian in his shed that he had bought at auction and was thinking of selling. Of course I didn’t hesitate in going to look at it, and a deal was soon struck.

Several things were appealing about the bike: the sidecar, the swathe of original documents that went with it, and the completeness and originality of it. The Scout had been “hot-rodded” in the 1950s by ex-racer, then mechanic, Edgar Fergusson. Receipts and documents showed that Edgar had fitted later model detachable-head barrels, Deluxe carburettor, later model Scout forks and more modern ‘well-based’ wheels as opposed to the original ‘beaded edge’ rims. All modifications were most probably aimed at improving useability with the sidecar attached. The amazing, and fortunate, thing is that the original parts had been kept in crates and were sold to me with the bike – enabling a relatively easy restoration back to its original factory build!

After a problematic ride through the hills, which involved my wife getting out of the sidecar and pushing, I decided to ‘unhitch’ the sidecar and use the Scout as a solo machine. It wasn’t a difficult decision to completely restore the bike due to two factors; firstly it had been painted with a red-primer using a house-brush sometime in the past, and secondly it had an engine failure after its last outing as a solo.

The restoration turned into a multinational affair. The wheels were rebuilt in New Zealand by a chap who supplied the new correct beaded edge rims and spokes, assembled the wheels, painted them and shipped them back to Australia. The original HX Schebler carbie was rebuilt by a master of the art in the US who goes by the single name “Cotten” and the saddle was restored also in the US by the nice folk at “The Saddle Shop” in Florida, who have correct stamps for the logos for period American seats. The Australian content was also expertly carried out. The mechanical work done by David was first class, as was the respray by Ken Langeley’s crash shop and the impeccable (as always) detailed paint linework done by Troy Craddock at Nightmare Designs.

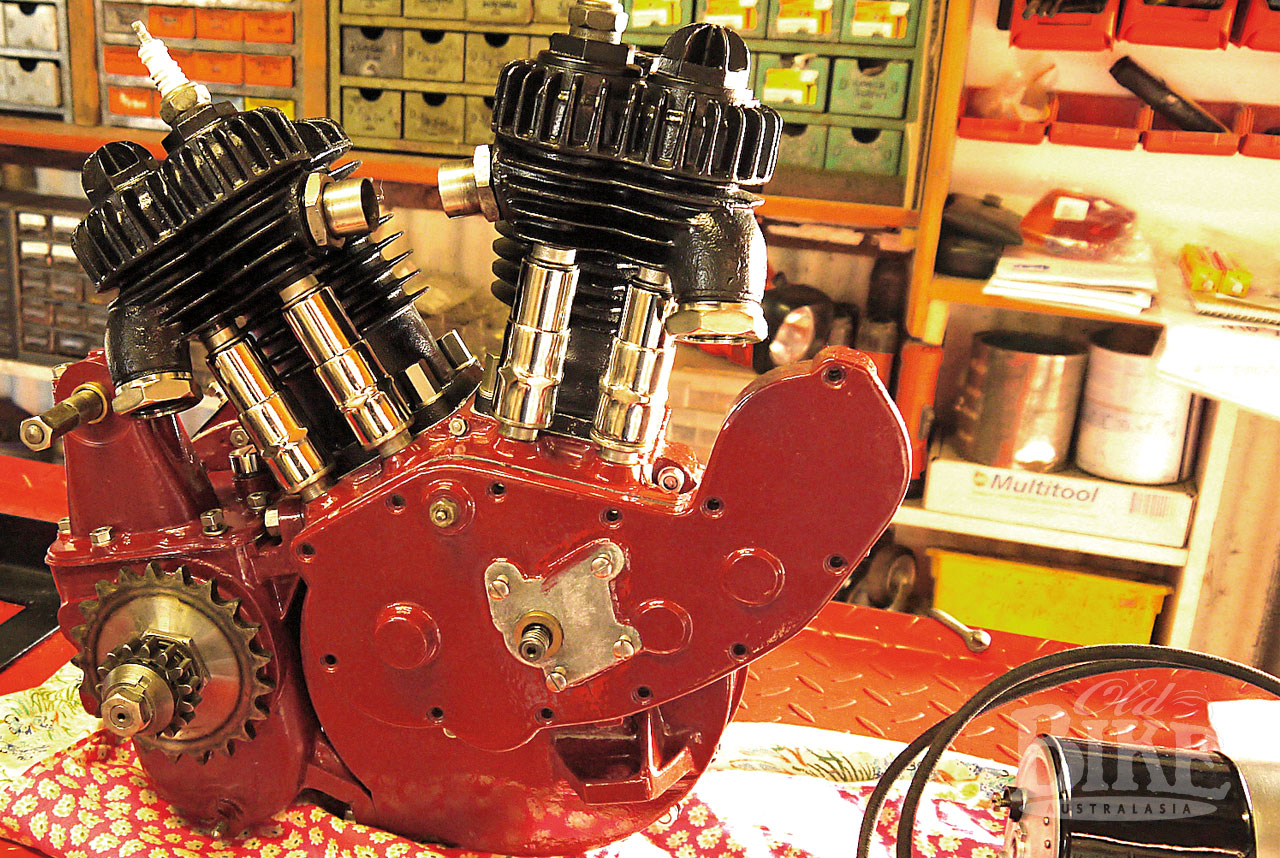

Of course, none of my restorations are to my satisfaction without correct high quality plating. I won’t use anyone other than Greg and his crew at “A-Class Metal Finishers” at Lonsdale (Adelaide). The Scout plating is a combination of nickel finishes. To achieve the right period look on some of the nickel parts (not dull, but not bright either) I got parts plated in modern satin nickel then spent hours polishing them to the right sheen, to simulate the original Watts Nickel process of the period. The only area that I didn’t plate as per factory original was the cylinders, these I painted with heat proof black for practicality reasons – the Adelaide summer requires optimal heat dissipation.

Restoration of the finely detailed toolbox lock was carried out by a true artisan, international jewellery designer (and friend) Peter Coombs. I taught myself how to restore Corbin speedometers and carried out this restoration work, with the aid of Doc Shuster’s book on Corbin speedos and parts from Janus Napierala from Canada.

The end result was a bike that looked great, was smooth, and comfortable to ride, but I just could not get used to the foot clutch and the handling wasn’t up to the vintage Norton standard I’ve become used to. For these reasons and to fund the completion of other projects, the bike was put on the market a month or so after Jim came around to take the photos of it. The bike has now been sold and gone to a good home; an enthusiast with his own private museum in central Victoria. The bike now sits in luxury accommodation in good company.

The story doesn’t quite end there though, the next project to complete to the same (if not better) standard is my 1913 Thor Model U. Thor motorcycles were made by the Aurora Automatic Machinery Company of Aurora Illinios, who also made the engine castings for Indian before Indian had their own foundry. The Thor has full history from new as I bought it from the original owner’s family – and it completed a cross US journey in 1914 mentioned in newspapers – but that’s a story for a future edition of OBA!”

Specifications: 1924 Indian Scout

Engine: 596cc 42-degree side valve v-twin.

Bore x stroke: 2 ¾” x 3 1/16” (69.85mm x 77.79mm)

Capacity: 606cc, 37 cubic inches

Transmission: 3-speed gearbox with helical-gear primary drive, oil bath. Foot-operated clutch. Chain final drive.

Frame: Cast lug and steel tubing, brazed together.

Suspension: Front: Girder with trailing link, leaf-springing.

Rear: Rigid.