From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 87 – first published in 2020.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Rick Benson, Gordon MacDonald, Peter Davies and OBA archives.

In the brutal days when the world was discovering the spectacle of Formula 750 racing, bravery was needed in big doses.

Genuine ex-works racers are thin on the ground, especially Suzukis, which were usually consigned to the crusher on completion of their racing life. The factory triple cylinder water cooled TR750 (officially code named the XR11), as opposed to the various home-brewed examples that today sparsely populate the grids of Classic Races around the world, are rarely seen in action as the spare parts for these dried up long ago. The TR750, internally, had many unique components, particularly in the bottom end of the engine, and in the transmission. Two TR750s are known to survive in Australia, and one (a later 1975 model) in New Zealand. The example featured here has a particularly poignant Australasian history, but more of that later.

TR750: The real story

Formula 750 racing was all the rage in the early ‘seventies. In Europe, the inaugural 1972 Imola 200 has gone down in history for Ducati’s 1-2 by Paul Smart and Bruno Spagiarri, but that grid was full of fledgling 750s, works and privately developed, including a trio of factory Moto Guzzis, and an MV Agusta for Giacomo Agostini. Across in USA, the appetite for the new formula was even more fervent. After Honda’s somewhat fortunate win in the 1970 Daytona 200, the Japanese factories scrambled to get a slice of the action, while BSA/Triumph soldiered on with their 750 triples and Harley-Davidson announced a production run of customer XR750s.

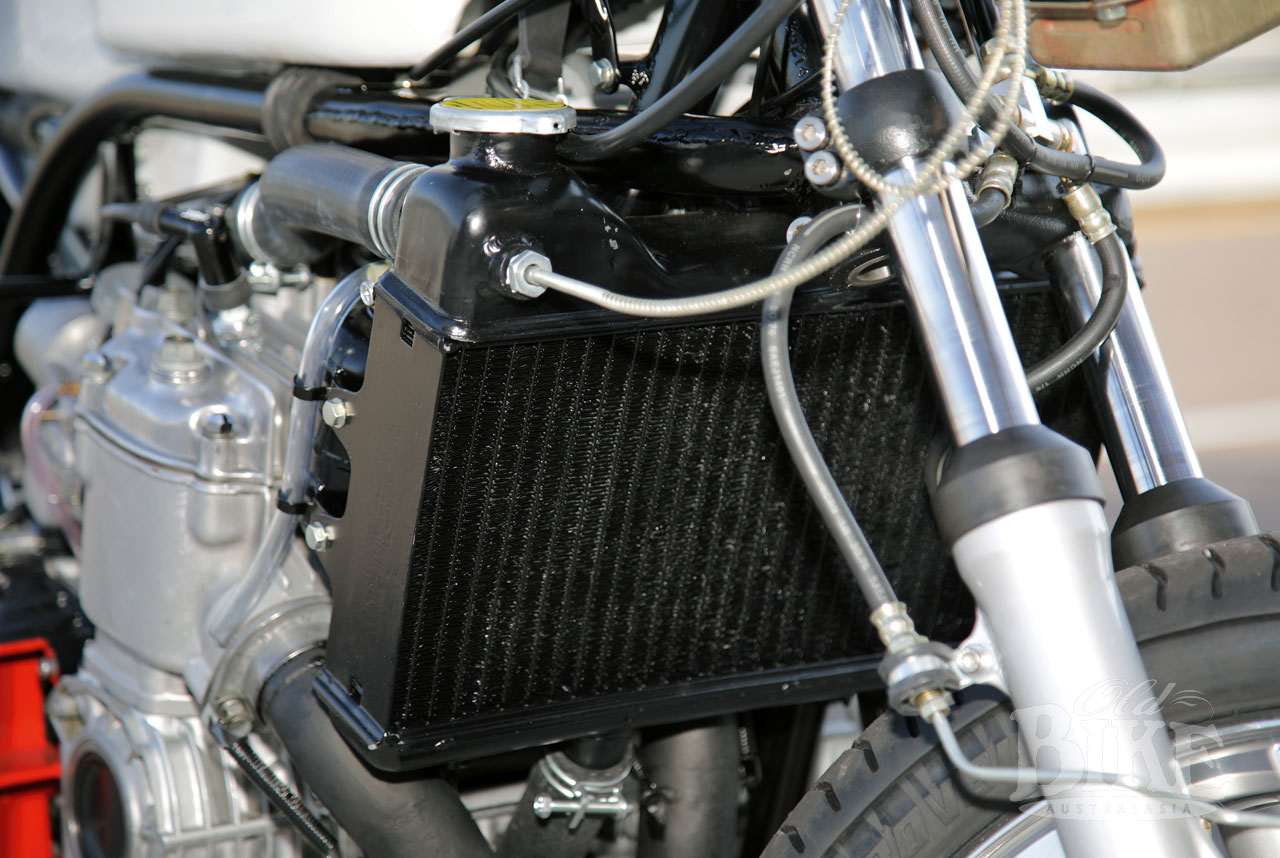

Up to this point, Suzuki had been racing their twin-cylinder air-cooled TR500 with moderate success. Art Baumann had given the factory its maiden US win in 1969 at Sears Point, California on a TR500, but the release of the road-going GT750 (affectionately known in these parts as the Water Bottle) in 1971, paved the way for a fresh attack. Water cooling provides more stable expansion rates of engine components, allowing finer tolerances, notably in pistons and bores, which provided a quantum leap in eliminating (or minimising) the bugbear of the racing two-stroke, engine seizures. By providing a fairly constant temperature for engine components, variables such as jetting could also be stabilised without being affected by changes in the weather. Power is consistent and reasonably predictable.

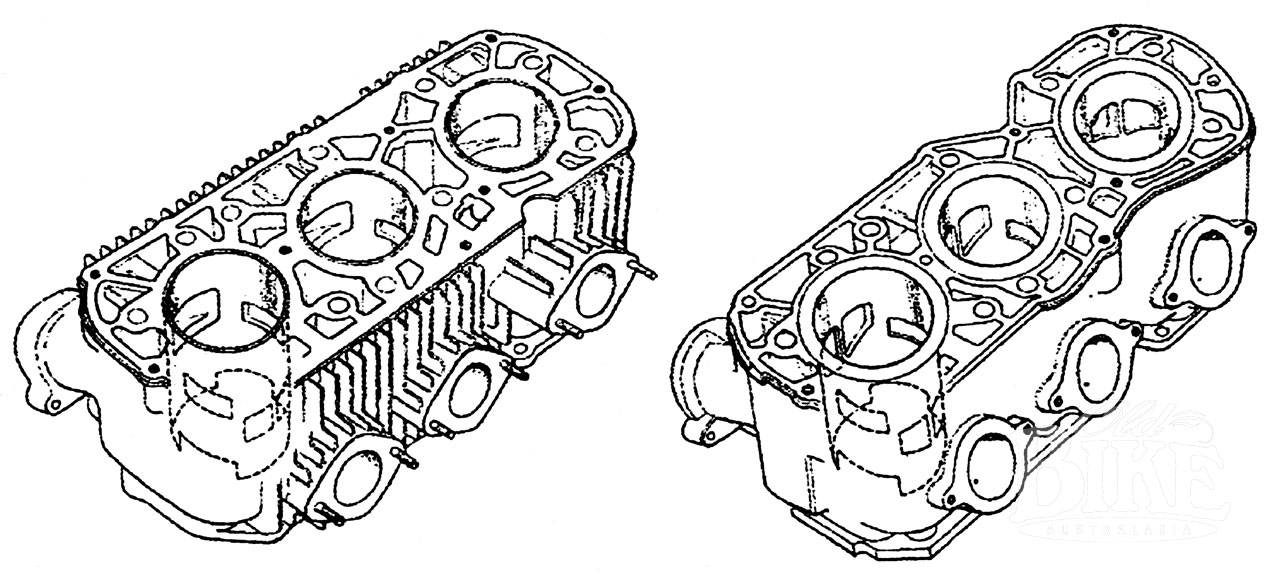

The main problem for Suzuki was that the AMA, which controlled the racing scene, had an ‘Old Mates’ deal via a rule in 1968 banning liquid cooling – ostensibly on the basis that hoses and other components could break, spilling coolant onto the track. However in 1971 that rule was modified to permit liquid cooling provided it was standard on the engine on the model approved for racing. Enter the TR750, racing version of the GT750, with the Daytona 200 firmly in its sights, a reputed 103 hp on tap at 8,000 rpm and a respectable racing weight of 173kg. For the 1972 running of America’s biggest race, Art Baumann put his TR750 on pole at 110. 3 mph, recording an incredible 171.7 mph through the speed trap. But the Suzuki’s power was also its bete noir, shredding tyres and flogging chains. In its original guise, the TR750’s engine unit closely mirrored the roadster, almost. One subtle difference was the castings for the cylinders and heads, the components having a markedly different appearance to the road items, with no vertical finning on the block. AMA rules at the time stated ‘cylinders to be of original casting material’, which they were, but the external appearance differed from the road GT750. Later in the 1972 season, Jody Nicholas gave the TR750 a maiden win at Road Atlanta, but a protest by The Hansen Kawasaki team (which had finished second and third) saw all three Suzukis disqualified over modified top ends, and the team was parked for three races until new (legal) replacement parts arrived from Japan.

Suzuki USA team rider Ron Grant brought a works TR750 to Australia for the inaugural Pan Pacific Series in November/December 1972, and after winning the series, hopped the Tasman to compete in the New Zealand Marlboro Series as part of a five-man USA squad. According to legend, it was the outspoken Grant who named the TR750 the ’Flexi-Flyer’, in reference to its scary handling characteristics. For 1973, the Suzukis were further, if slightly, refined within AMA rules, but overall the season was a disappointment, with gearbox failures, tyre woes and other problems. At Daytona, Geoff Perry, now a full member of the US team, was leading until sidelined with ignition failure.

And then, for 1974, along came the Yamaha TZ750, which was legal under new rules that required 200 examples of a motorcycle – road-derived or not – to be eligible for AMA competition. Suzuki soldiered on for another two seasons, while Kawasaki eventually adopted liquid cooling for the H2-based 750 triple that became the KR750. As road racing wound down in USA (only 4 championship events were scheduled for 1975), Suzuki pulled the pin on the TR750 effort, as well as development on the GT750 as they concentrated on their own four-stroke multi – the GS750.

Road and track: The differences

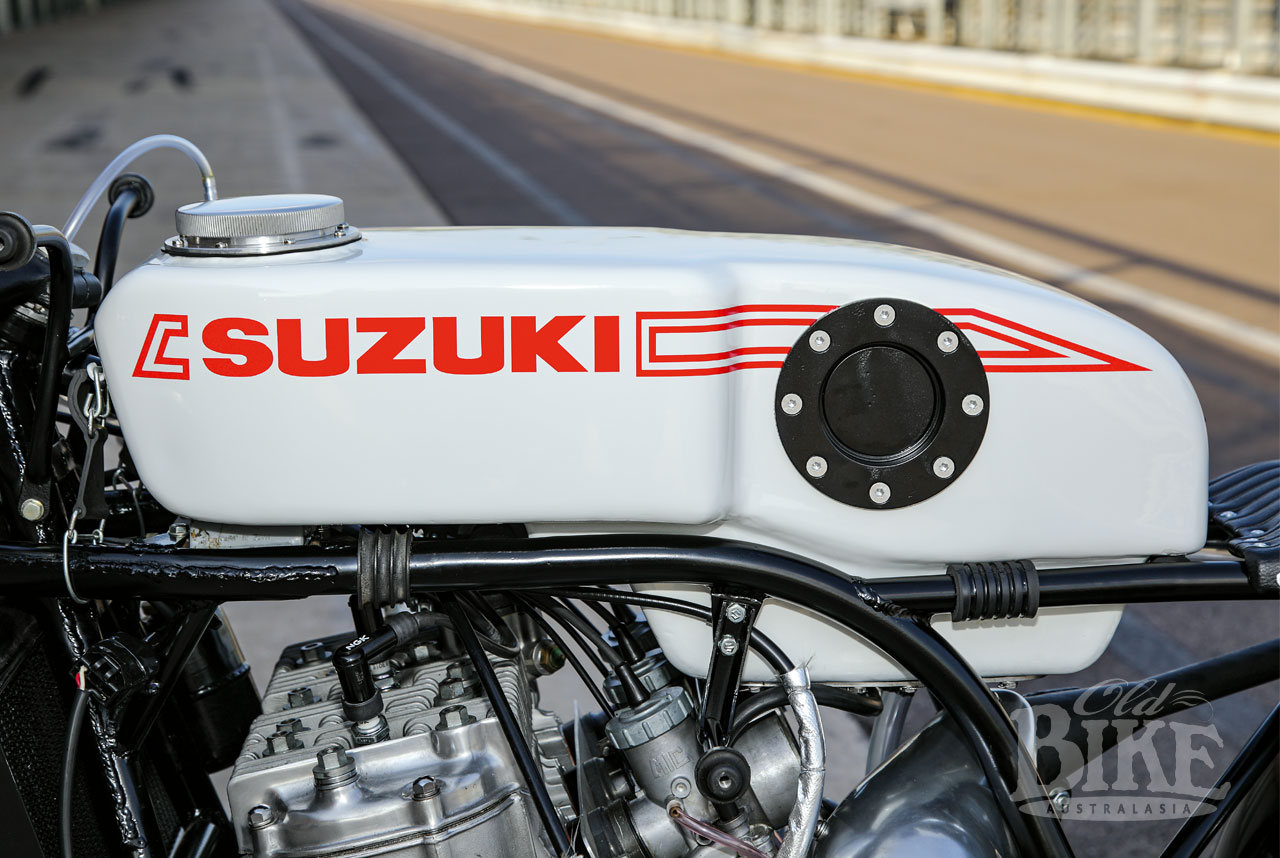

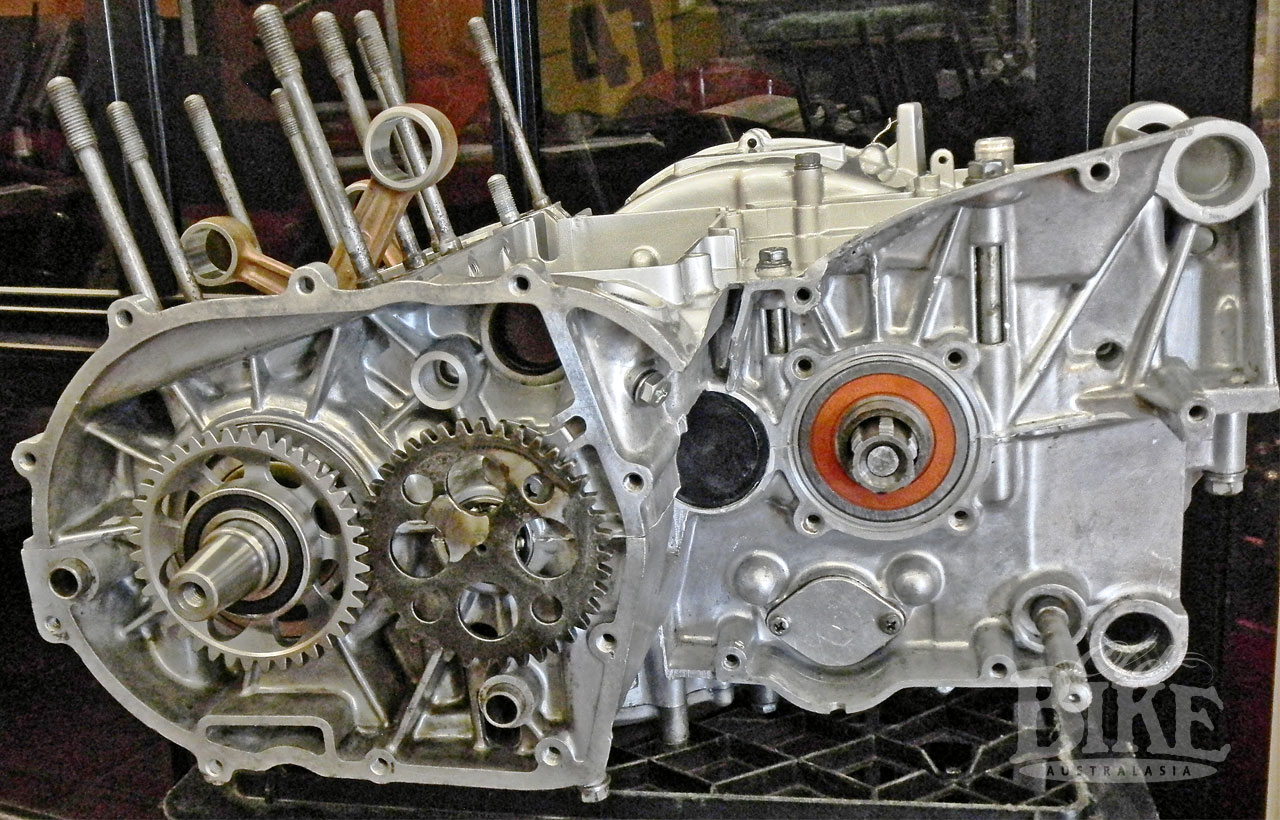

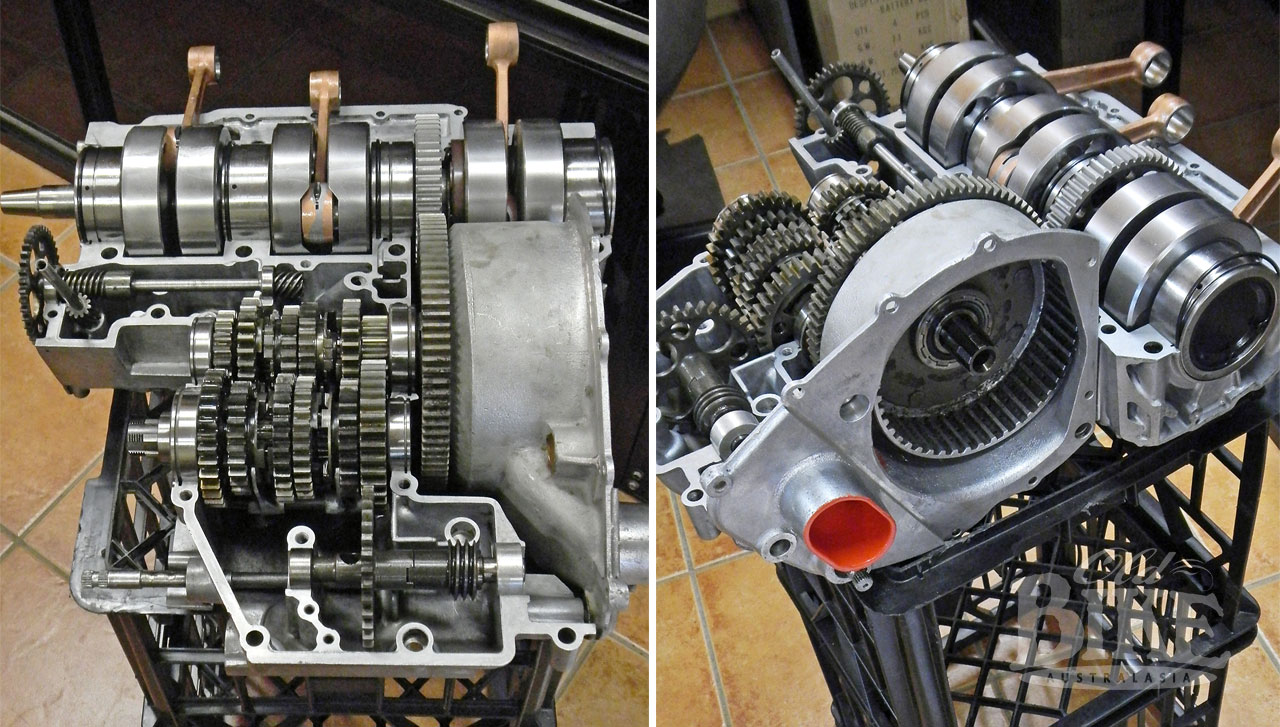

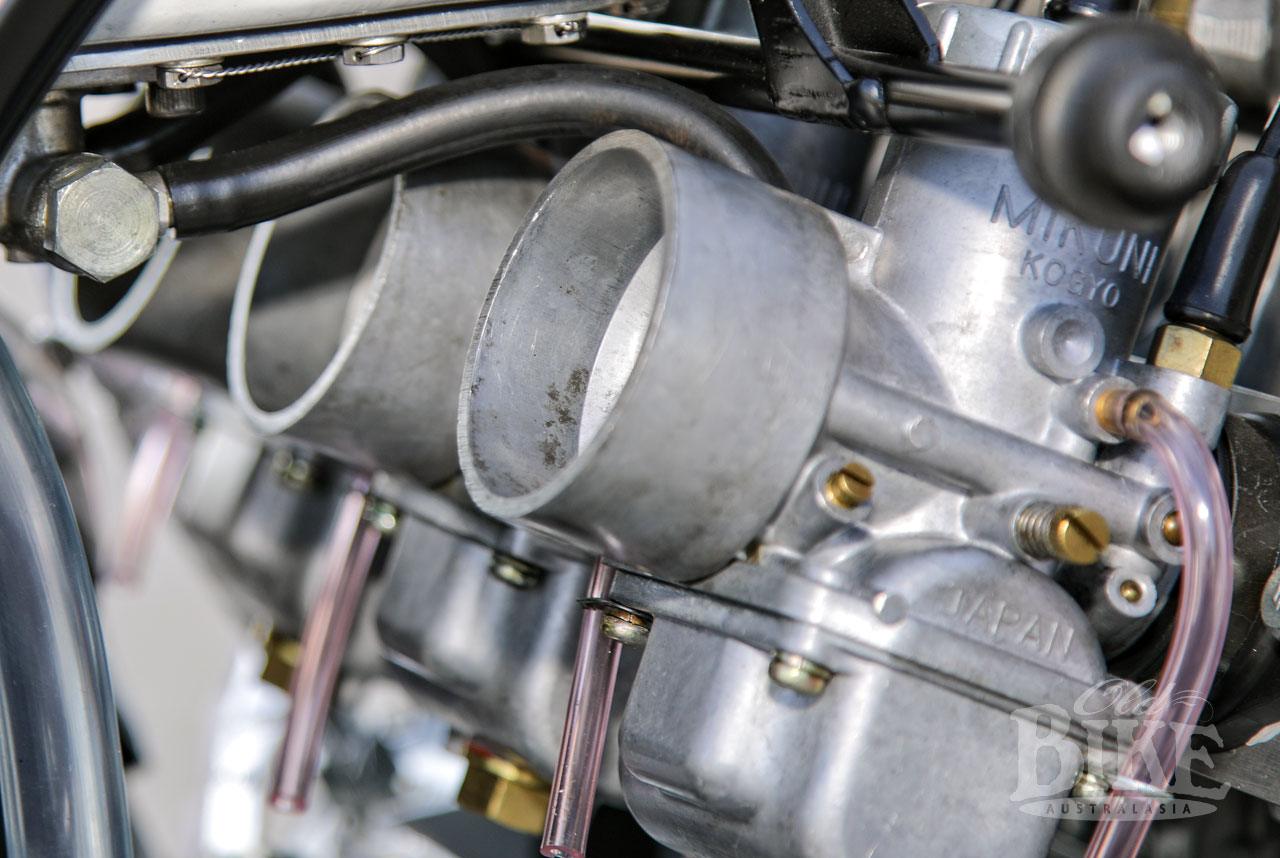

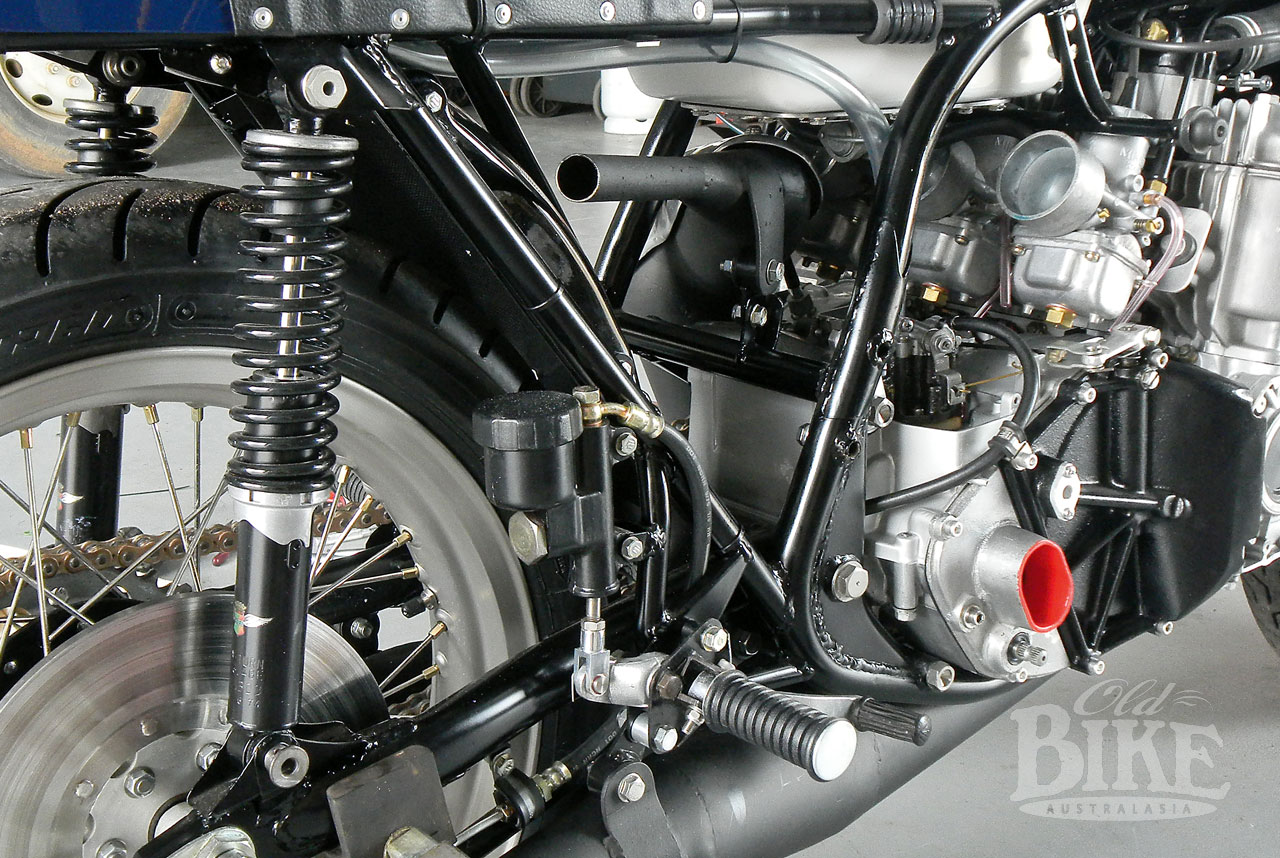

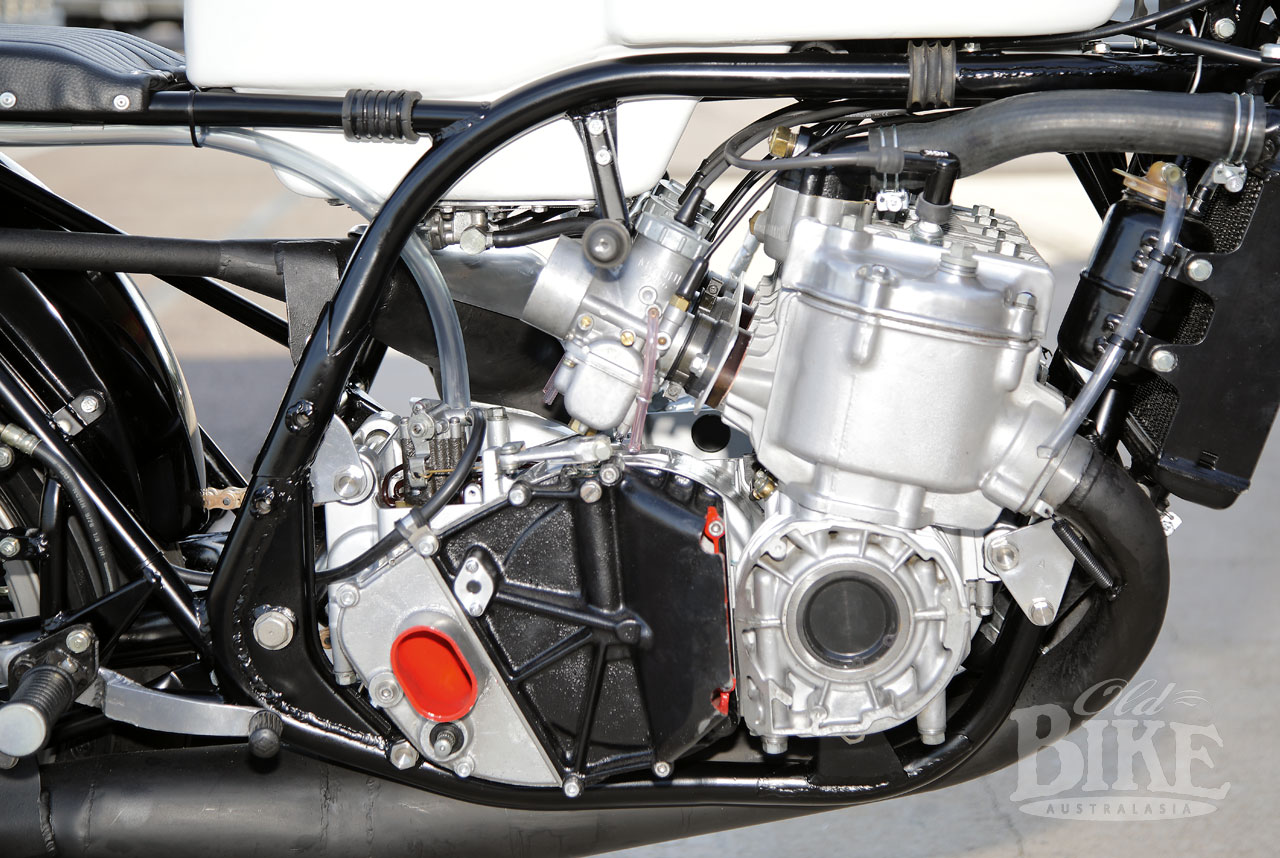

To comply with AMA rules, the TR750 as introduced in 1972 used a standard crank, barrels and heads. In fact, the crank on the TR differed in having large triple roller bearings on the right side to reduce crankshaft flex, while straight-cut primary gears replaced the quieter-running helical gears of the GT. Three 34mm magnesium carburettors, especially made by Mikuni, are steeply angled at 15 degree to the vertical for downdraught, and with the cylinders themselves inclined at 12 degrees forward when in the frame, the float chambers sit at 27 degrees. These carbs were made so the actual floats sit level. Forks on the TR were specially created by Suzuki in Japan using 35mm tubes and internals developed on the company’s highly successful motocross bikes, as were the rear shocks. For 1972, the TR750 used solid stainless steel discs, two front and one rear, with the front calipers from the GT750. For 1973 the TR750 front calipers changed to a Suzuki copy of the Lockheed, and the rear disc became ventilated. The fuel tank was designed in USA by A.J.Foyt and Bruce Burness with a ‘Dry Break’ quick filler, allowing five US gallons of fuel mix to be added in just three seconds. Ron Grant said that the fuel taps needed to be turned off during refuelling or the pressure from the incoming fuel would blow the floats in the carburettors.

For the 1972 season, the US Suzukis were fitted with one-piece handlebars instead of clip-ons. A close ratio five-speed gearbox was used, but this was replaced with a six-speeder for the 1975 season. The racer used the standard Suzuki oil pump to pressure feed the big end bearings, as well as running a 25:1 petrol/oil mix in the tank, but the oil pump was sometimes discarded. With the bottom end thus lubricated by oil mist only, crank life dropped alarmingly.

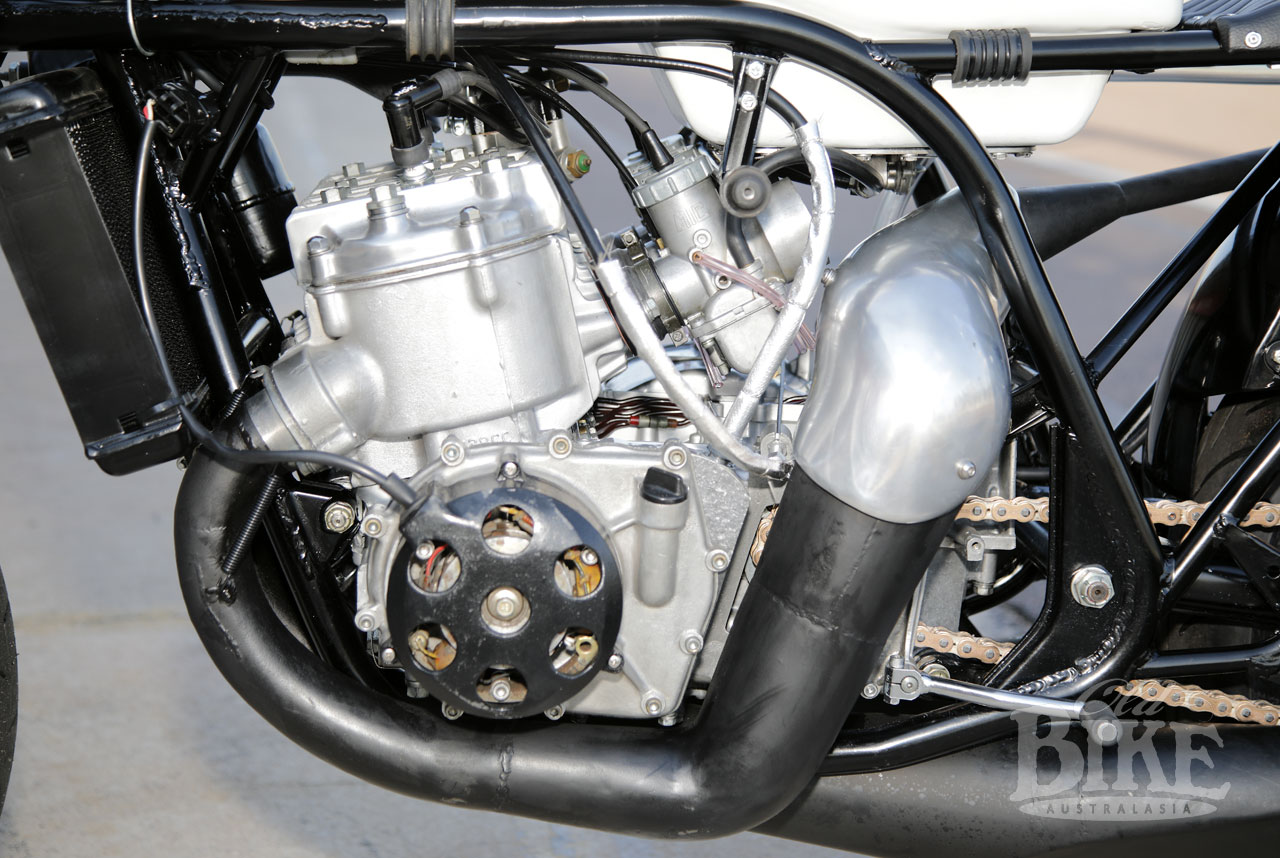

Inside the one-piece cylinder block, the mild GT porting was naturally altered, although standard pistons were used. To prevent the piston rings being trapped, the widened exhaust ports were vertically bridged. The cylinder head employed squish bands to raise the compression ratio from 6.7:1 to 7.2:1. With no generator required, the right side crankshaft was shortened and the aperture in the crankcase blanked off. At the other end, the starter motor was removed and a shorter mainshaft used for the ignition unit. The dry clutch is completely different from the road version, with eight steel/sintered bronze friction plates and seven steel plates, but retaining six springs.

The frame had the duplex loops made from one-inch diameter steel tubing, with the sub frame in ¾ inch. Later in 1972m Suzuki increased the size of the tubes to 1 1/16” and 7/8” respectively. Oval section steel is used for the swinging arm with a fabricated sheet steel section for the swinging arm pivot. Originally, the TR750 used wire spoked wheels, but these were soon replaced with cast magnesium versions, some made in England by Peter Williams and others by Morris in USA.

Tyres were of course the weak point as the 750s took over the racing scene, to the point that Suzuki abandoned Dunlop after numerous failures and used Goodyear at Daytona in 1972. Dunlop bounced back however and soon had a brand new rear, the Racing 200, for use on high-speed banked circuits – a virtual slick before the term became widely used. For other tracks, Suzuki generally stuck with the tried and proven KR83 which was narrower with a higher profile.

A survivor

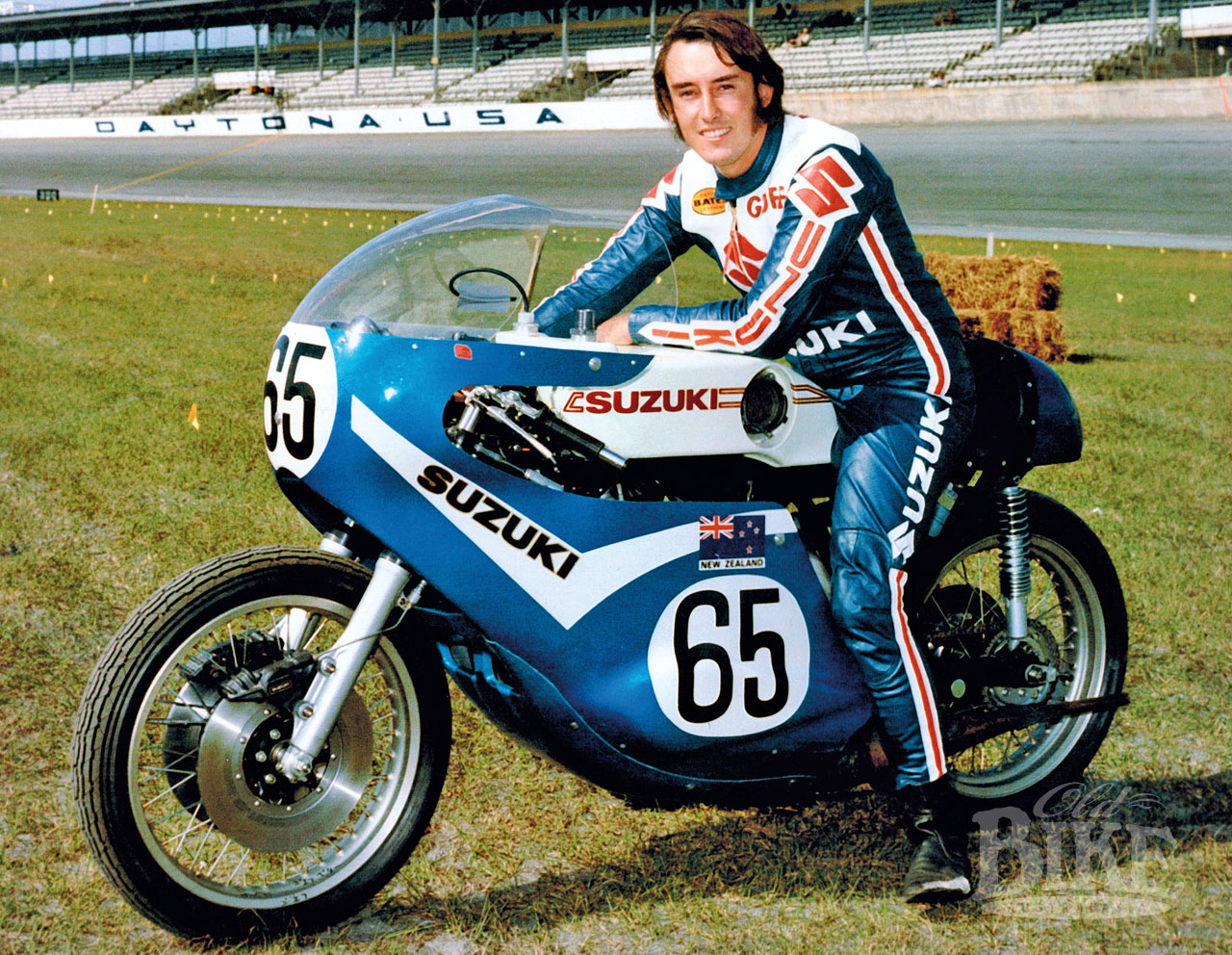

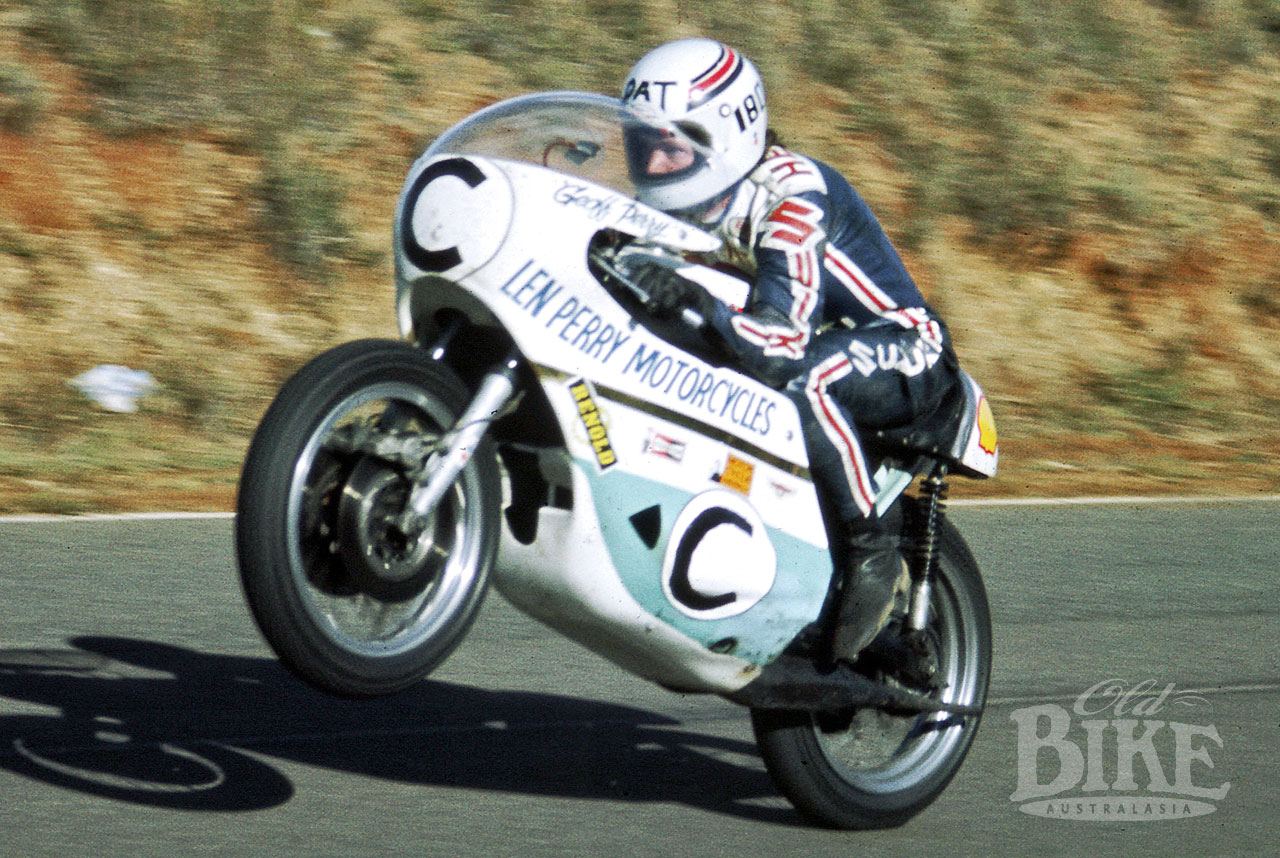

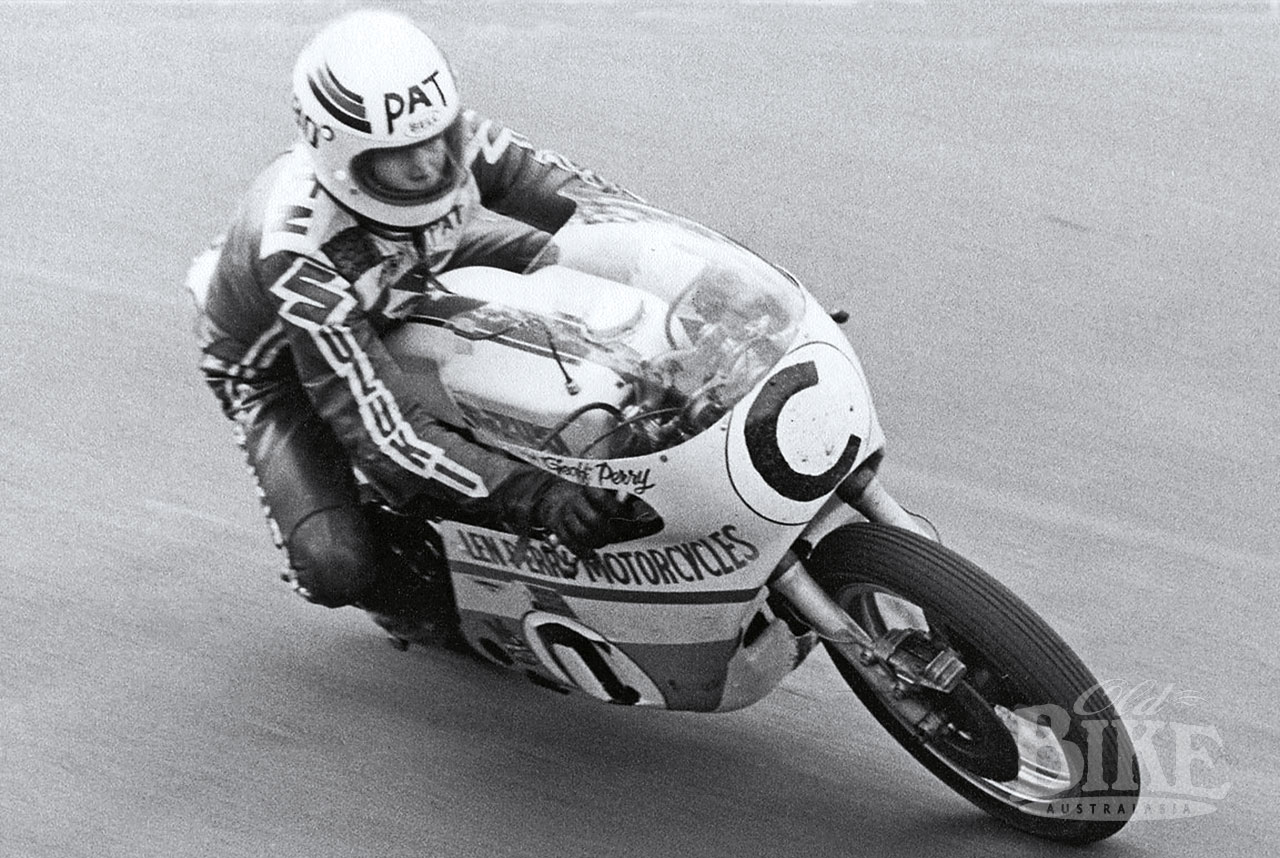

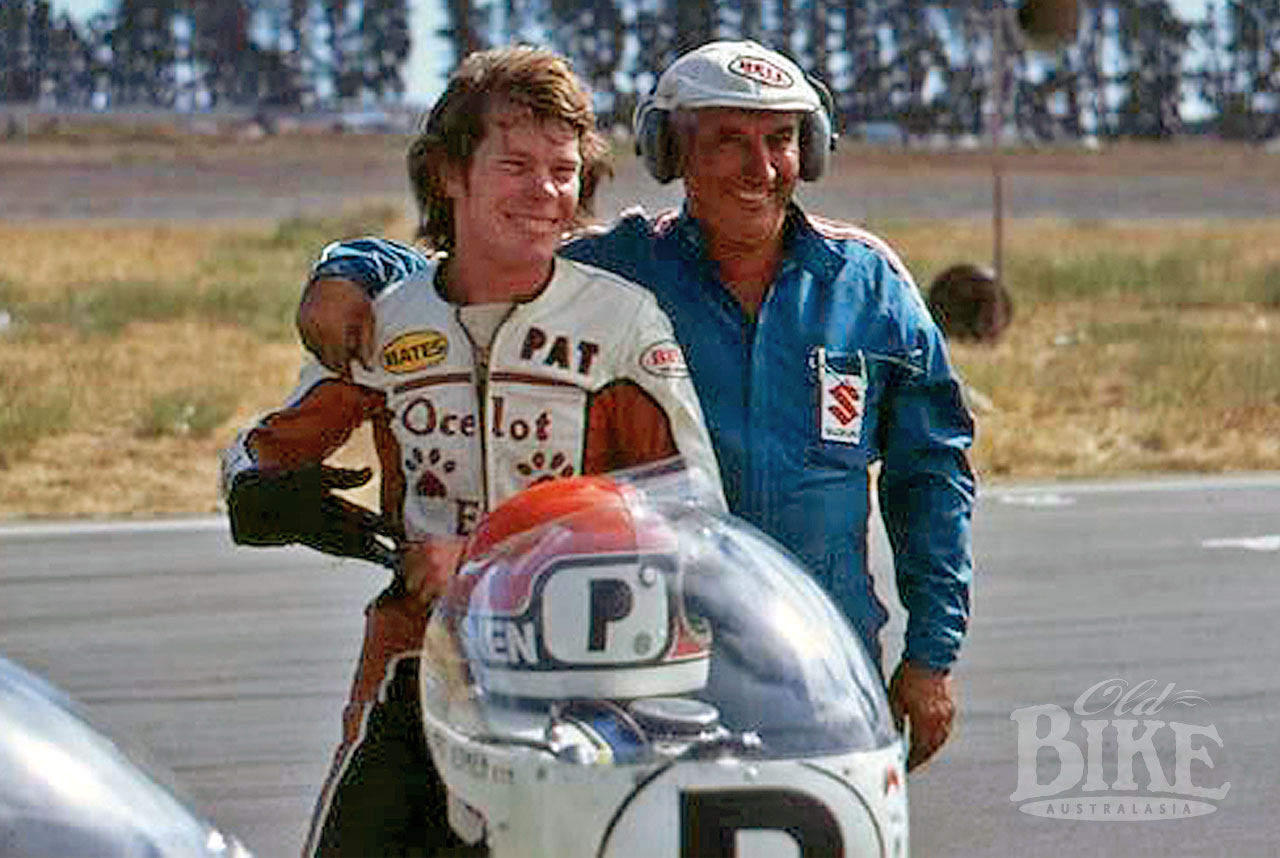

The motorcycle featured here was supplied new in 1972 to Rod Coleman, head of NZ distributors South Pacific Suzuki, to be used by Geoff Perry for events in New Zealand, Asia and the USA. Perry contested rounds of the AMA series in 1972 with this TR750 as a semi-factory rider. His best result in the US was second place at the Ontario Motor Speedway in California in October. This was billed as the world’s richest race with a race purse of $53,200 USD and was won by Paul Smart on a Kawasaki. Perry was rewarded with a full berth in the US Suzuki team for 1973 and supplied with a new TR750, and won the AMA round at Road Atlanta before losing his life in an air crash in July. His 1972 mount was given to Geoff’s father Len following Geoff’s death and returned to New Zealand. Subsequently Len Perry allowed the TR750 to be used by others, notably American Pat Hennen. Pat raced it at Bathurst in 1974, where he finished fourth in the main Unlimited Grand Prix – the race that featured the epic dice between Warren Willing and Gregg Hansford.

The young American also raced in the NZ Marlboro International Series in 1974/75 and 1975/76, winning the round at the Cemetery Circuit in Wanganui both years. For the 75/76 series, Pat raced a later model TR750 acquired from Suzuki USA by Rod Coleman. This machine, the ultimate evolution of the model, is now in the Southward Museum in New Zealand.

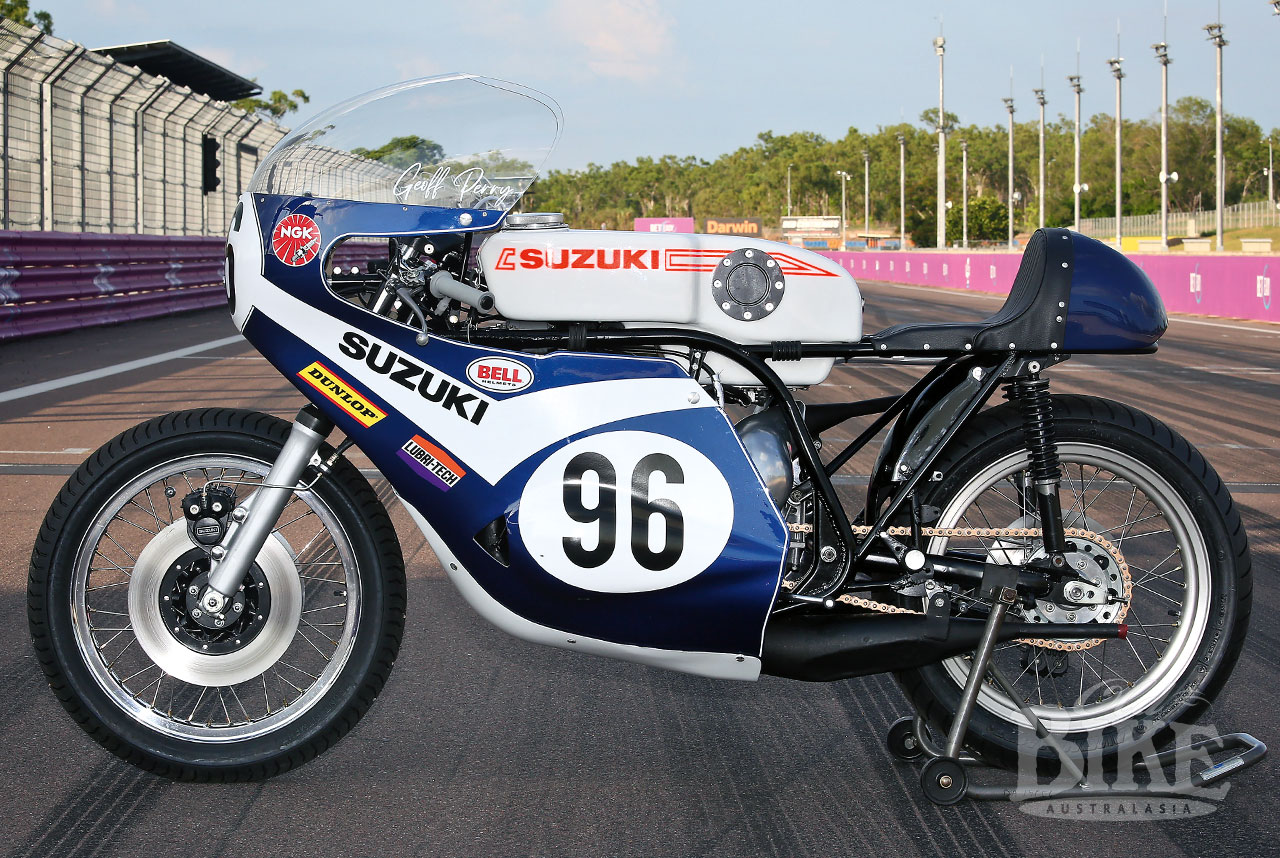

Later both John Woodley and Graeme Crosby rode the TR750. At Pukekohe in 1977, Woodley defeated Trevor Discombe’s Yamaha TZ750, then was unbeaten at the following meeting at Levin to take out the inaugural Geoff Perry Memorial Trophy. Woodley subsequently purchased the Suzuki from Len Perry but did not race it again. In 1999, John sold the complete bike to Peter Shires in Darwin, Northern Territory. 19 years later, fellow Darwinian Gordon MacDonald acquired the Suzuki in a dismantled state and began a complete restoration.

A big job

Gordon MacDonald was pleased that the special factory bits that distinguish the TR750 had remained with the bike during its racing career. These include the titanium steering stem with the drilled titanium fork crown bolts, wheel bearing spacers in titanium, with the same material used for the waisted engine mounting bolts. Still fitted were the original Suzuki disc rear brake, the hollow cast magnesium fork crowns, magnesium hubs, ignition cover and dry clutch cover, the special Suzuki front forks, and the ‘Dry Break’ fast-fill fuel tank.

As well as re-enamelling the painted parts, the magnesium components were dichromated prior to painting. The rear shocks were completely overhauled, as was the radiator, with bent fins straightened before pressure testing and painting. The rear brake master cylinder assembly was rebuilt with new piston, cups, brake lines and fittings.

The engine itself was totally rebuilt, the crankshaft fitted with new connecting rods, big end and main bearings, rebored cylinders with new pistons and rings, the block and head resurfaced by Bruce Woodley of Powerflow. The gearbox was also rebuilt with new bearings and seals. Numerous brackets and mounts were overhauled. Cosmetically, the rear rim was re-anodised and the front rim polished, new spokes sourced and nipples anodised to the correct colour and the wheels rebuilt with new bearings and seals. All brake calipers were overhauled with new seals, pistons, lines and pads, the discs machined and disc carriers painted.

Temperature and tachometer gauges were refurbished, the electrical system and CDI rewired. New replica handlebars and new footrests were fitted. The original fairing needed a complete restoration and the Zeus fasteners replaced in the belly pan before painting and applying the correct decals. After a dry assembly, the engine was again stripped before being fitted to the chassis. Interestingly, the chassis for this machine has main tubes of 1 1/16” with 7/8” tube used for the sub-frame.

It took much hard work and considerable research, but the TR750 that once carried riders of the calibre of Geoff Perry, Pat Hennen, John Woodley and Graeme Crosby is once again a living, breathing thing. The photos of the restored motorcycle were taken at Darwin’s Hidden Valley Raceway, and those present were astounded at the TR750’s shattering exhaust note from the un-muffled expansion chambers. One can only imagine the music echoing around Daytona’s speed bowl as fearless Art Baumann rocketed to pole position during qualifying for the 1972 200 Mile Race.

Specifications (factory): 1972 Suzuki TR750

Engine: Three cylinder water cooled two stroke with piston port induction.

Bore x stroke: 70mm x 64mm

Claimed power: 103hp at 8,000 rpm

Maximum torque: 9.5 kg/m at 7,000 rpm

Transmission: 5-speed constant mesh, gear primary drive with straight-cut gears. Chain final drive.

Spark Plugs: NGK 10.5ep.

Clutch: Dry 10 plates

Carburation: 3 x 34mm Mikuni

Frame: Tubular steel double cradle.

Suspension: Front: Suzuki 35mm telescopic forks

Rear: Suzuki/Showa spring/damper units

Brakes: Front: 233mm discs with twin Suzuki calipers

Rear: 200m single disc with Suzuki master cylinder.

Wheelbase: 1416mm

Dry weight: 160kg

Fuel capacity: 23 litres

Oil tank capacity: 1.9 litres

Tyres: Front: 3.25 x 19 Dunlop KR76

Rear: 3.50 x 18 Dunlop KR83

Maximum Speed: 174 mph (Ron Grant, Suzuki Test Track, Japan)

Standing quarter mile: 11.2 seconds (128 mph) with Daytona gearing.