From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 86 – first published in 2020.

Story: Nick Varta • Photos: Jim Scaysbrook

It was 1973 and the British motorcycle industry was writhing through a series of very public death throws. Many once great names were already gone: AJS, Matchless, Velocette, Sunbeam, Ariel and (to India) Royal Enfield. Others were hanging on by virtue of mergers, takeovers, and largely, government grants; Norton, BSA and Triumph among them.

As if the atrophy itself, combined with catastrophic corporate mismanagement, flawed designs and dubious marketing were not enough to battle with, there was the toxic, and worsening, relationship between workers, management, and unions. The so-called British disease. And if the motor industry appeared to be suffering more than its share, try newspaper publishing, mining and steel production.

However for our purposes, the epicentre of the battle was in the British Midlands – the London-based AMC (AJS, Matchless, Norton, Francis Barnett and James) having already disappeared in 1966, when it was acquired by Manganese Bronze Holdings, a family company whose primary business was manufacturing marine propellers. MBH was owned by Dennis Poore, son of the founder, a successful amateur racing driver, qualified engineer, WW2 Wing Commander, and founder of the venerable British motor sport magazine Autosport. The new entity was named Norton-Villiers, and its primary aim was to flog Norton Commandos to the US market, which it did rather successfully.

By 1972, BSA/Triumph was in deep trouble, and a request for government assistance was met with the condition that it be merged with Norton-Villiers, under Poore’s chairmanship. It was a reluctant marriage, but in July 1973, Norton-Villiers and the BSA/Triumph company became Norton Villiers Triumph, Manganese Bronze’s, but Poore decided to sell off this business to raise capital with which to purchase the remains of AMC and its brands, as well as the engine manufacturer Villiers. Poore had influence in high places, and managed to convince the UK government to contribute sizeable funds to combat the threat from the Japanese manufacturers.

As NVT chief, Poore made himself very unpopular with the 4,500-strong workforce by announcing the closure of Triumph’s Meriden factory and axing around 3,000 jobs, with production to be consolidated at the BSA factory at Small Heath in Birmingham. The workers replied with an occupation of the site that dragged on for nearly two years, before securing funding from the newly-elected Labour government to produce 750cc Bonnevilles. All these were marketed by NVT, which itself went bankrupt in 1977. This resulted in further government loans, and what was officially known as the Meriden Motorcycle Co-operative took over the rights to the Triumph name and pressed on with production of the twins, which staggered along until the Meriden Co-operative itself sunk under the burden of unpaid loans in 1983.

Children of the Revolution

So let’s hark back ten years to 1973 and have a look at what was being turned out of the Meriden site. At the time, it was all about Bonnies, and specifically about satisfying the US appetite for them. To many, the “real” Bonneville ceased with the adoption of the oil-in-frame chassis and associated hardware. The frame, as been oft noted, had a towering seat height of some 875 mm, although the official specs stated this as 800mm. Whichever, it was a challenging climb for many a short-in-the-leg Brit, and many did not go much on the look of the petrol tank either, with its single centre bolt fixing and a profile that some likened to a Humpback Whale. However compromised it may have been, the chassis did have its good points. The new-for-1971 Ceriani style forks where a marked improvement with better damping and 150mm of movement, although devoid of the traditional rubber gaiters, allowing dirt and water into the lower legs and bursting their seals. When combined with Girling rear units which were now fitted with softer springs, the result was rather pleasant handling.

Another polarising styling exercise was the abbreviated front mudguards, which by their very nature fell short of their intended purpose. These blades dispensed with the normal holding brackets and instead used thick wire mounts which quickly succumbed to the effects of vibration. Instead of the conventional headlight brackets, the light unit was now also suspended on wire brackets, and often suffered the same consequences. More criticism was levelled at the new-style Lucas handlebar switches, which were said to be awkward to use and far from waterproof.

As Triumph staggered along, many of the perceived shortcomings were addressed, or partially addressed. The problem of the tall seat height was not so easy to solve, but a combination of shorter fork springs, shorter rear shock absorbers, and a less luxuriously padded seat with a shorter front section at least produced a height of 790mm, which was worth mentioning in marketing terms at least. Further progress was later made by lowering the rails of the rear sub frame from where they were welded to the main oil-holding section under the rear of the fuel tank. This of course involved a considerable redesign below, with a different battery casing, squatter side panels and a revised air cleaner. The resultant shift in weight distribution produced a better handling machine, but all these changes further hammered the company’s bottom line, which continued to struggle following a massive £22 million loss in 1971 trading.

To make matters worse, the Meriden blockade had become a permanent fixture, with a motley collection of furniture set up outside the front gate to house the omnipresent picket by disgruntled workers. After a temporary cease-fire in 1974, an agreement was finally reached in mid 1975 between NVT and the Meriden workers, but it was too late, much too late. While Triumph had been stalled, the opposition had accelerated away. By 1977 NVT was bankrupt, with its assets sold to the Meriden Cooperative. The Co-op itself managed to exist (with government handouts) until 1983, when the Triumph name and the Meriden site were acquired by property developer John Bloor. For five years, Bloor allowed Les Harris to produce Bonnevilles in small numbers until this too folded.

A survivor

We have marvelled at Don Tomkins’ restorations before, the Adelaide-based enthusiast responsible for not just his own work but for many of the machines in his group of friends around McLaren Vale. Don’s Machine is not the venerated Bonneville, but a humble single-carb 650 twin, which was officially marketed as the Tiger 650.

Don’s Tiger 650 is a 1973 model, and represents the definitive specification of the 650cc twin. It also is somewhat of a parts-bin special, although this is not necessarily a bad thing. The front brake for instance is the Triumph full width hub, which preceded the unloved conical (or comical to many bemused owners) and was marketed in this case in place of the disc brake that had first appeared two years previously. This would have been a cost consideration, allowing a lower, more attractive retail price, and doubly to use up surplus stocks of the otherwise quite acceptable and quite attractive drum brake. The rear brake is a non quickly-detachable version of the Triumph conical.

Conventional headlight ‘ears’ were used, with the bullet-style headlight shell instead of the flat-back type on the earlier Bonnevilles. Up front was the handsome and robust full-length front mudguard with tubular stays that added some degree of fork bracing once everything was bolted up. On Don’s bike, there are no fork gaiters but period photos show that these were fitted on some versions.

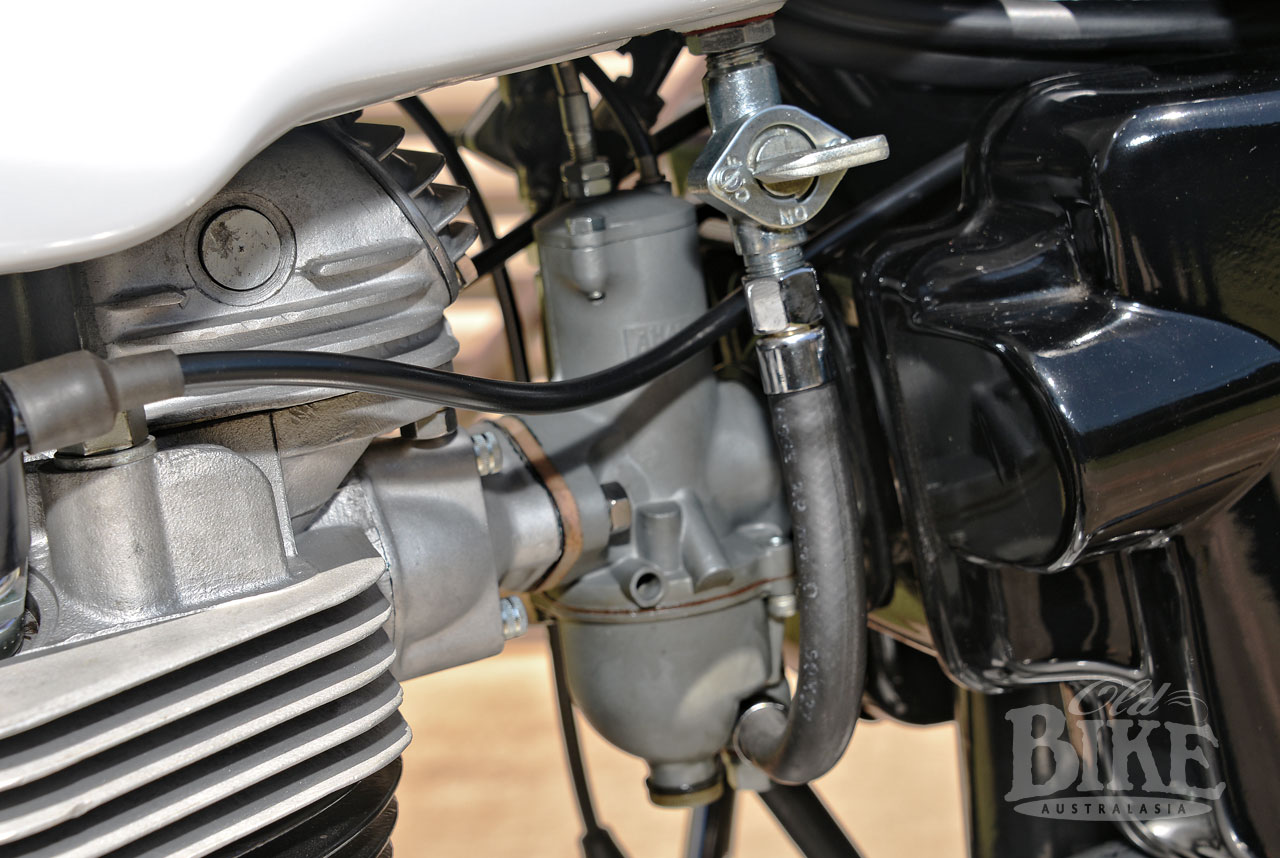

Some 1973 model twins (the T120R and T120RV among them), were fitted with Nippon Denso instruments as supplies of the Lucas items dried up, but Don’s has a Smiths speedo and tacho, plus a non-standard ammeter. Again, although many of the 650 twins received the old ‘high’ frame from accumulated stocks, Don’s Tiger 650 has a low frame. Just what has occurred in this motorcycle’s previous life is unknown, but during the rebuild Don found the original carb would not meet the air box. Fortunately a replacement rubber mount came from Trojan motorcycles in Sydney which allowed everything to line up. Trojan also supplied the long tapered reverse cone mufflers which certainly do not look out of place. Don says the bike is fitted with a later model 1979 seat which originally hinged from the other side and has a slightly different pattern. This was reversed during the restoration process. Eagle eyes will spot an extra pillion footrest attached to the top of the left side rear shock absorber. Once unfolded, Don says this greatly assists in getting the bike onto the centre stand.

The fuel tank, in what the Brits referred to as the ‘bread box’ shape, is the optional 4 gallon capacity with knee rubbers (3 gallons was the catalogue version, with cast badges). The blue and white colour scheme is Don’s own choice. In other respects, the bike is standard, with the five-speed gearbox that came on stream in 1972.

All in all, the Tiger 650 is not a particularly remarkable motorcycle, but it is significant in the fact that it represents the dying gasps for the model that first saw the light of day, as the 650cc Thunderbird, in 1949. And like all Don Tomkins’ restorations, it is superbly presented and functional.

Specifications: 1973 Triumph Tiger 650

Engine: Air cooled parallel twin OHV.

Bore x stroke: 71mm x 82mm

Capacity: 649cc

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Gearbox: 5 speed.

Carb: Amal R930

Electrics: Lucas alternator

Tyres: 3.25 x 19 front, 4.00 x 18 rear

Brakes: Triumph 2LS full width front, single LS conical rear

Wheelbase: 1420mm

Dry weight: 173kg