By all accounts, Francisco Xavier Bulto (also known as ‘Paco’) was a formidable man with a typically robust Latin personality, and he loved motorcycle racing with a passion shared by legions of his countrymen. It was this passion that led to the formation of Bultaco (the named derived from the first three letters of Bulto and the last three letters of his nickname) in 1958.

Bulto was a director of the Montesa company, which began motorcycle production in 1944. Montesa had steadily built its business into a range of two-stroke bikes, using racing success as its main form of promotion. However the move to larger premises in 1957 coincided with a slump in the Spanish economy, and a decision by the company’s majority shareholder to suspend all racing activity met with strong disapproval from Bulto. So strong, he quit Montesa and started his own concern, taking with him several of Montesa’s key employees.

Bultaco was set up in an old farmhouse and in March 1959 launched its first model, the 125 cc Tralla 101 (Spanish for whiplash). Beautifully styled and a spirited performer, the Tralla was an instant hit, particularly after a near-standard model finished second outright in the prestigious Montjuic 24 Hour Race in Barcelona later in the year. Several features of the Tralla 101 became synonymous with all subsequent Bultacos, such as the big exhaust port and polished crankcases, and, on the road bikes, the suede strip in the centre of the seat. In 1962, the Tralla’s engine was squeezed out to 196 cc by over-boring – the maximum size obtainable using the original crankcases, to create the Metralla 62, Metralla being Spanish for Shrapnel in the artillery sense. The following year, the Tralla 101 was superceded by the 102 and was basically visually identical (apart from some minor things) to the Metralla 62 in all respects except the capacity of 125 cc.

And so we come to the subject of our story, the Metralla Mk2 of 1966. Now a full 250 cc (well, 244.3 cc actually), the ‘big’ Bully sported a 5-speed gearbox, poked out 27.6 hp at 7,500 rpm and was good for a genuine 100 mph. In this respect, it came squarely into competition with the Suzuki T20, another 100 mph 250 and which carried a good deal more customer-friendly tweaks, particularly in the electrical department, than the Metralla. But in reality the two bikes were poles apart as you would expect in a Japan versus Spain situation; one perfectly behaved with impeccable attention to detail (and an automatic oiling system called Posiforce), the other a rorty little pug with a real Latin temperament and few frills.

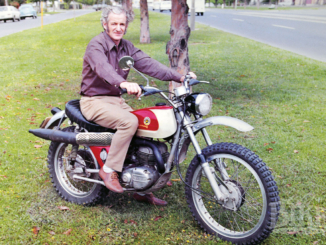

At this point I will introduce John Somerville, the doyen of the Metralla in Australia; a man who is a self-confessed Bultacoholic (he owns over 20, including the ex-Tommy Robb factory Isle of Man machine). Some years ago John did all Metralla owners a big favour by writing the definitive book on the subject “Bultaco. Mi obsesion’, which covers absolutely every aspect of the model, from its inception as the Trala in 1959 to its ultimate form as the Metralla GTS of 1979. The book is out of print now but if you’re contemplating a dalliance with a Metralla, you’d be well advised to seek a second hand copy.

Australian deliveries of the Metralla Mk2 began in 1966, and the first models were available in either red/silver or black/silver. John sums up the market thus, “ The type of person who bought these bikes fell into two categories. (1) Those who knew just how well these bikes went and were not blinded by all the chrome and lights of the Japanese bikes at the time, and (2) Those who bought them just because they were the cheapest 250 at that time (In 1967 the Metralla Mk2 had a retail price of $640.00 in NSW). The Metralla needed plenty of preventative maintenance to keep it running properly, and the replacement of all nuts with Nylock nuts and Loctite to stop bits vibrating off. The lights usually needed attention to get a few extra candle power and stop them from blowing/vibrating bulbs. Fork oil needed to be increased from the 55 cc specified to 100 cc to allow the forks to work and the rear shocks needed regular servicing. On some bikes the crank had not been properly aligned at the factory so the bike would vibrate a bit but properly align the crank and it was a very smooth and powerful engine (for 1966). Apart from that just regular maintenance was required but woe-betide the rider who did nothing!”

Spartan it may have been, but the Metralla had some very nice touches, notably the fully-enclosed rear chain. Early models used a cast alloy section to enclose the rear sprocket, with individual rubber sleeves covering the top and bottom chain run. This not only significantly prolonged the life of the chain, it kept the back end of the bike free of muck. Early fork legs had no drain plugs, which was a major inconvenience and meant each leg had to be removed to chain the oil. This was rectified on latter models.

A major difference between Australian (and European) and American models was the headlight and taillight. US regulations called for lights that were approved by various state authorities, so the normal direct lighting system was a no-go. In place of the Spanish electrics, 12-volt Lucas lights were used. American models, some of which found their way to Australia, also have high-mounted one-piece handlebars instead of the individual clip-ons for local models. Metrallas come with both 6 and 12 volt for the lighting system, and the 12 volt system is usually fitted with a Zenner diode. As John Somerville says, “The standard lights on the Metralla Mk2 as set up at the factory are reputed to be almost useless for riding at night, but they can be improved. The main killer of headlight and tail light bulbs is vibration. Fit a rubber washer on each of the headlight mount bolts, between the headlight shell and the support brackets on the front forks. To get a good headlight, replace the standard one with one from a Japanese bike; they will fit straight into the Bultaco headlight rim. These have the benefit of concentrating the light forwards (the Bultaco Hensev light reflects almost as much light up, down and sideways as forwards) and also have a rubber-mounted bulb for greatly increased bulb life. A Zenner diode should be fitted to restrict the flow of excess current. To further improve your lights, disconnect the speedo light (the speedo probably doesn’t work anyway) and the high beam indicator light. If your system is 6 volts, fit a 12 volt tail light bulb, it will draw half the amps of the 6 volt bulb. Reduce the air-gap between the coils and the magneto flywheel to the absolute minimum.”

The 250 engine, although following basic two-stroke principles, was a very spirited performer. Early models used a 27 mm Amal Monobloc carburetor, which was later replaced with a 30 mm Monobloc and finally a 32 mm Concentric Mk.1. Another later modification was the fitting of an oil tank inside the right hand tool box with a hand-operated pump which delivers oil to the petrol tank. John Somerville describes the procedure that precedes the use of the oil tank. “Pump out 10 strokes of oil into a measuring cylinder and divide by ten to determine how much oil is pumped per stroke. When filling up with petrol, simply multiply the number of strokes of oil you pump into the tank by 25 (for a 25:1 mix) and fill the tank with this amount of petrol. I have been using the oil pump successfully on my Metralla for 31 years. It works perfectly and is very worthwhile having”.

From what has been said so far, it is obvious that as a road bike, the Metralla left a few things to be desired, particularly compared to the more sophisticated offerings from Suzuki and Yamaha at the time. But as a sports machine, it punched far above its weight. In standard form for Production Racing the Metralla was a rocket, as evidenced by its domination at Bathurst, where it won the 250 Production Race in 1967 (Kevin Fraser first, Allan Arnold second), and 1969 (Terry McDonald first, Kevin Fraser second). At Oran Park, where the Lightweight Production was one of the hardest-fought races on the program, Kevin Fraser was virtually unbeatable.

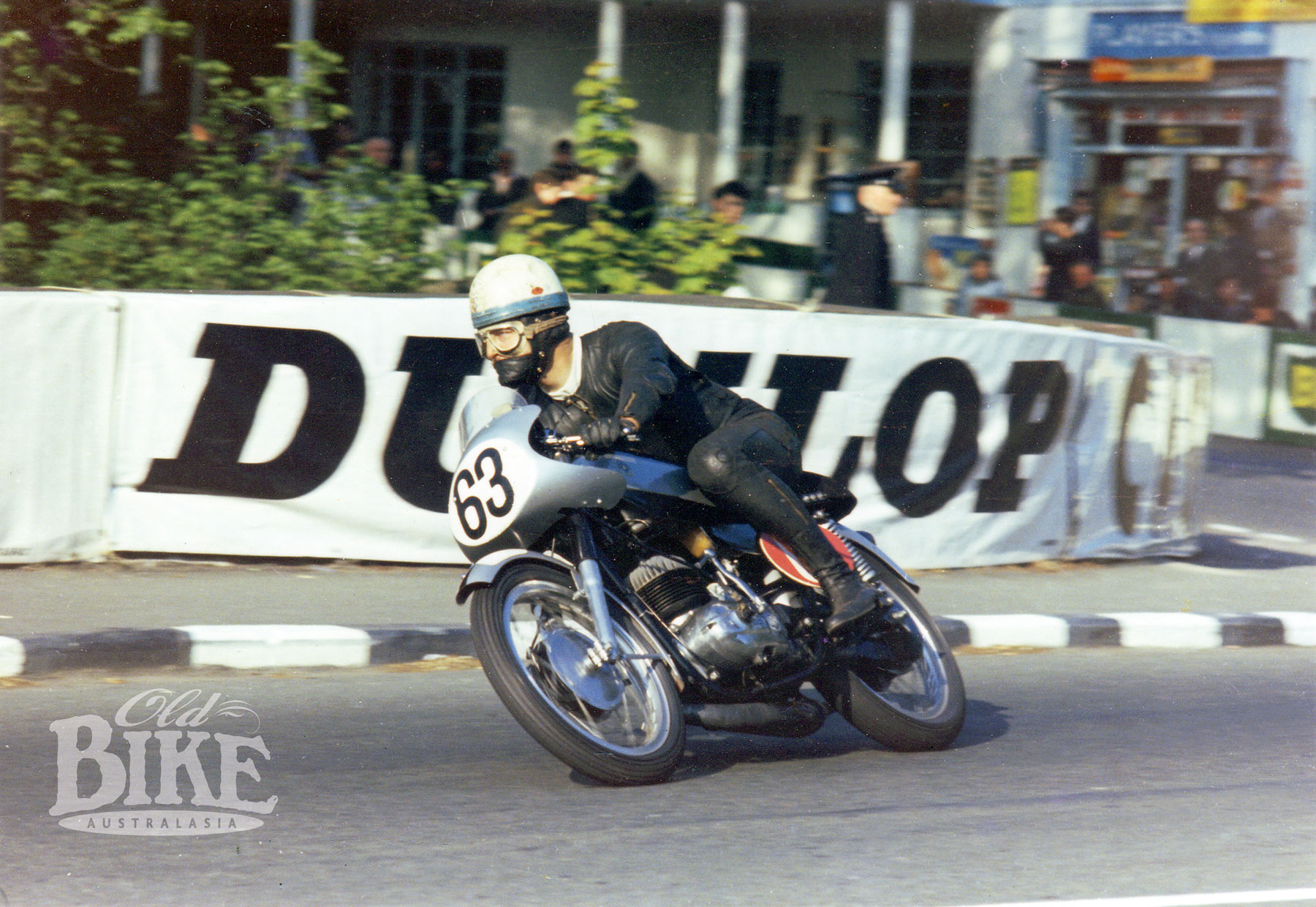

A Race Kit was offered for the Metralla, and under the very loose regulations for the Isle of Man Production TT, was eligible for the 1967 event. A three-bike team of factory bikes entered by Harry Lindsay, the Bultaco importer for Southern Ireland, cleaned up the 1967 Production 250 TT, with Englishman Bill Smith first (averaging an impressive 88.63 mph) Ulsterman Tommy Robb second, and Australia’s Kevin Cass sixth. The Robb bike eventually came to Australia to Wangaratta collector Ken Lucas, and is now owned by John Somerville. The standard ‘race kit’ comprised a race-ported barrel, a piston with the inlet skirt shortened by 2 mm, a head giving 12:1 compression ratio, FEMSA electronic ignition, expansion chamber exhaust, close-ratio gearbox, bigger jets and a plastic bellmouth for the carburetor. There was also a large capacity fiberglass fuel tank with different supports and strap, a racing style seat, dropped clip-on handlebars, rear ser footrests, rear brake lever and gear lever, and a bikini-style fairing. It was a fairly straightforward job to fit the race kit to a standard Metralla, and the result was a competitive racer, at least until the Yamaha twins took over.

Only 5,508 Mk2 Metrallas were made between 1966 and 1974, so they are a comparatively rare machine today and highly sought-after. The Metralla name did survive post-1972, but in quite a different form. The Metralla GT was aimed at the US and used the redesigned engine from the later 250/370 motocross models, in a conventional full loop cradle frame with a slightly upswept exhaust silencer. This was superceded by the very similar Metralla GTS in 1977, and finally by the 1979 GTS which used cast alloy wheels instead of spoked items.

The Metralla mob

One sunny day in February I journeyed to Newcastle on the invitation of Eric Hoskins (Ocker to his mates) to have a look at his 1973 Metralla, engine number 23 05012 (23 being the Metralla designation); one of the last made. His mate Wayne Cummins came along as well with his 1966 model (230 1495), so I was able to compare the subtle differences between the two. The most obvious external difference is the four-stud head on the earlier model, which gave way to six studs. Wayne’s bike had the alloy rear sprocket enclosure while Eric’s is plastic. On the left side crankcase of the 1971 model is another difference, a larger bulge in the outer cover to accommodate a slightly larger flywheel. Wayne’s bike also had a different gear change linkage arrangement.

Starting the Metralla, with its left-side kickstarter, is an acquired knack, and some owners never really mastered it, resulting in a motor loaded up with fuel that would subsequently resist all attempts to make it commence. A short squirt on Wayne’s bike brought back a few memories. My father sold Bultaco and Ducati from his shop in Sylvania in Sydney’s south during the late 1960s. Quite a few Metrallas went out the door, mostly to satisfied owners and club racers, but one disgruntled customer brought his back, complaining of a lack of performance. He had previously owned a Panther single, and was clearly used to trundling along at minimal revs. I could see from the way he puttered up to the front of the shop on the Bultaco that he had probably never even entered the Metralla’s powerband. After listening to the chap’s grumblings about how the Bully ‘wouldn’t pull your hat off’, my father asked me to take it around the block and see what I thought. I took off at a reasonably sedate pace but once out of sight I gave it full throttle and away it went. I entered Port Hacking Road about half a mile from the shop and wound it up through the gears until I reckon I was doing about 85 mph (in a 35 zone!). As I scorched past the shop front where dad and the customer were standing I swear I could see the owner’s jaw hit the ground. Minutes later I returned the bike and said, ‘with a smaller main jet I reckon it would do 100 mph’. Off he rode, very sheepishly.

So 40-odd years later, here I was back on a Metralla, but there was no chance of full throttle runs this time. Still, you can feel the little bike wanting to go underneath you as the revs rise, and both Wayne and Eric say they really enjoying blowing off much bigger British bikes on club runs! Eric was a pretty handy racer in his day and still owns several nice Bultacos, including a luscious 350 cc TSS. Unfortunately my short time on the Metralla came to an end all too soon, but it was enough to revive the memories of the crisp handling, excellent brakes and that ripper little engine that just wants to rev and chase after bigger bikes.

Specifications: 1966 Bultaco Metralla 250

Displacement: 244.29 cc

Engine type: Single cylinder, air-cooled two-stroke

Power: 27.50 HP (20.1 kW)) @ 7,500 RPM

Top speed: 161 km/h (100 mph)

Compression: 9.0:1

Bore x stroke: 72.0 x 60.0 mm (2.8 x 2.4 inches)

Gearbox: 5-speed

Final drive: Chain

Front tyre: 2.75-18

Rear tyre: 3.00-18

Weight including fuel and oils: 112.0 kg

Fuel capacity: 14 litres

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Sue Scaysbrook